12 Jul 2024 | Europe and Central Asia, Israel, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Russia, United Kingdom

A Russian art collective which was due to open a show in London highlighting the plight of opponents of the Putin regime claim their exhibition was cancelled at the last minute because one of them was Israeli.

The Pomidor group was founded in Moscow in 2018 by the artists Polina Egorushkina and Maria Sarkisyants, but the duo was forced to relocate two years ago after the Kremlin crackdown on opposition activity. Egorushkina now lives in London and Sarkisyants in Ashkelon in southern Israel.

Their latest show, Even Elephants Hold Elections, was part of an ongoing project about free expression designed to challenge people in democratic countries to understand life in an authoritarian regime and reflect on their own experience. Pomidor’s work includes embroidered banners celebrating political prisoners which the artists display in friends’ windows and phone booths on the street.

Among these are tributes to Viktoria Petrova, imprisoned in a psychiatric unit for anti-war social media posts, Mikhail Simonov, a 63-year-old pensioner arrested for comments on other people’s social media and 13-year-old Masha Moskaleva, who was taken away from her father after drawing anti-war pictures at school.

The show was due to open on 3 July at the Metamorphika Gallery in east London. But on the evening before, the two artists were told the gallery had received messages raising concerns about “inappropriate behaviour” on social media.

This referred to two posts pinned on Maria’s Instagram account. One post from 7 October expressed her horror at the “terrible evil” and included the words, in Russian, “Israel my beloved, we are here, we are here to support each other, all my thoughts are with the kidnapped, let only them return home alive. Eternal memory to the fallen.” A second post marked the one-month anniversary and expressed solidarity with the Israeli hostages and their families.

Sarkisyants told Index they were called to an urgent meeting the next day: “They showed me the two posts and said you should clarify your position. I said, I am from Israel and there was nothing in the post but facts: 1200 people were killed and 300 became hostages.”

The gallery asked Pomidor to sign a joint statement with Metamorphika condemning “the Zionist regime”, which they refused to do. “I’m Israeli. I was there,” said Sarkisyants. “What they proposed was impossible for me to do”

After several hours of discussion, Pomidor suggested a compromise of putting the exhibition solely in the name of Polina, but the gallery demanded the collective remove all work connected with Maria. At this point the exhibition was cancelled.

Pomidor posted on Instagram: “The problem came up because Maria is from Israel.”

This is something the gallery strongly denies. Metamorphika founder Simon Ballester told Index: “We were really compassionate with her story. But we asked her to say she had empathy for Palestinians and was against the war crimes.”

Ballester said the problem came when Sarkisyants expressed her support for the Israeli government’s actions in Gaza.

“It’s outrageous” the artist told Index. “I told them I do not support Netanyahu or his government. I feel they betrayed us. We expected them to protect us, but they didn’t. But I support my country Israel and its people.”

Since the cancellation of the show, Metamorphika claims it has received over a thousand “hate mails, insults and threats”. According to Ballester, he and his colleagues have been accused of being “Nazis, rapists, antisemites and misogynistic scumbags”.

Asked if he now regretted cancelling the show he said: “I think it was the right thing. I’m sorry it was the day of the show. That was really unfortunate.” He said the gallery operated on humanist principles and was striving for peace and equality.

The Pomidor exhibition will next travel to Montreal in Canada and the artists are in discussion with a gallery in London to host the show later in the year.

21 Jun 2023 | China, News and features, Press Releases

Index on Censorship’s upcoming “Banned by Beijing” event will highlight the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts to censor and repress freedom of expression through an evening of art and performance. The CCP’s repression of human rights has been widely documented but few realise that their repression extends far beyond its borders, including into Europe. This event will provide an opportunity for attendees to see and hear what the CCP have tried to repress.

Earlier this month, the Chinese Embassy in Poland tried to block the opening of the exhibition, “Tell China’s Story Well”, by the political cartoonist and human rights activist Badiucao. Chinese embassies in Prague and Rome have previously made similar attempts to close his exhibitions. He will join the event to speak about his experience of transnational repression.

Uyghur campaigner Rahima Mahmut will also speak about her experience of transnational repression, and perform with her band the London Silk Road Collective. Mahmut previously contributed to a report by Index, which highlighted the transnational repression faced by the Uyghur community in Europe.

The event will also mark the opening of the Banned by Beijing exhibition, aimed at highlighting transnational repression from China. As well Badiucao’s artwork, works from husband-and-wife painting duo Lumli Lumlong and cartoonist and former secondary school visual arts teacher Vawongsir, will be displayed. The exhibition will run until 10 July.

The event will take place as we mark the third anniversary of the enactment of Hong Kong’s National Security Law. The exhibition will pay tribute to the 75-year-old British businessman and founder of Hong Kong’s Apple Daily newspaper, Jimmy Lai who remains in prison in Hong Kong, charged with violating the national security law among other offences. It will be the first time that Lumli Lumlong’s “Apple Man” will be shown in public.

Jessica Ní Mhaínin, Head of Policy and Campaigns at Index on Censorship said:

“This Banned by Beijing event will provide an opportunity to see a side of China that the Chinese Communist Party would much rather you didn’t. We want people to join us on the evening to stand in solidarity with those who are being subject to transnational repression. The event will send a clear message: dissident artists and performers cannot and will not be censored by the long arm of the regime.”

ENDS

NOTES TO EDITORS

- The event takes place on Tue, 27 June 2023 19:00 – 22:00 at St John’s Church in Waterloo and the exhibition will run until 10 July.

- Report into repression of Uyghurs in Europe: https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2022/02/landmark-report-shines-light-on-chinese-long-arm-repression-of-ex-pat-uyghurs/

- For more information, please contact Sophia Rigby on [email protected] or Jessica Ní Mhaínin on [email protected].

- The artists will attend the event in person and we can organise for interviews during the evening with any of the artists and Rahima Mahmut.

17 Sep 2020 | Music, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114914″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mehdi Rajabian is once again facing imprisonment. His crime? Including women’s voices in his music.

Rajabian is a musician in Iran, where women’s behaviour and expression – including their ability to sing in public or record their songs – is severely limited by the regime. But Rajabian has been determined to defy the authorities’ efforts to intimidate him, repress his art, and silence women’s voices. “I need female singing in my project,” Rajabian told Index on Censorship from his home in the northern city of Sari. “I do not censor myself.”

In August, Rajabian was summoned by the security police, who arrested him and took him to court. He was handcuffed and brought in front of a judge, who told him that the inclusion of women’s voices in his project “encouraged prostitution”. Rajabian was held in a prison cell for several hours but was able to post bail with the help of his family. He remains on probation and banned from producing music.

It is not the first time that the 30-year-old has faced imprisonment for his art. He spent three months blindfolded in solitary confinement in 2013, and was subsequently sentenced to six years in prison. He was released at the end of 2017 after undertaking a 40-day hunger strike. “I was completely sick after the hunger strike,” he explained. “When a prisoner goes on hunger strike, it indicates that he is preparing to fight with his life, that is, he has reached the finish line.”

After his release, Rajabian continued to make music and last year his album Middle Eastern was brought out by Sony Music. Every track on the album, which features more than 100 artists from across the Middle East, is accompanied by a painting by Kurdish artist and Index on Censorship award-winner Zehra Doğan.

But now Rajabian says that the pressure on him has become so great that it is extremely difficult for him to be able to collaborate with other musicians and to finish his next album. In August, a music journalist was arrested and detained in Evin Prison for several days after mentioning women’s music and referring to Rajabian in an article.

“Artists and ordinary people [in Iran] are all afraid to even talk to me,” he says. “I have been completely alone at home for years. Coronavirus days are normal for me.”

At home alone, he reads, watches films, and listens to music by John Barry. “I am currently reading Alba de Céspedes y Bertini’s books,” he told Index. But he spends most of his time reading philosophy. He believes that his interest in philosophy is one of the reasons why his music has been so targeted by the regime.

“The Iranian regime is not afraid of the music itself, it is afraid of the philosophy and message of music,” Rajabian explains. “Artists who do not have philosophy in their art are never under pressure.”

What does Rajabian believe the future has in store for him? “You can’t predict anything here. I am ready for any event and reaction,” he says. “But I still believe that we must fight and stand up”.

“I will continue to work, even if I return to prison,” he says. “I know that there is a prison sentence and torture for me, but I will definitely complete and publish [the album]. In Iran, making music is difficult for me because of the bans, but I have to make it.”

“Encourage banned artists,” Rajabian concludes. “They are not encouraged in their own countries. Be their voice.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”71″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Aug 2018 | Artistic Freedom, News and features, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

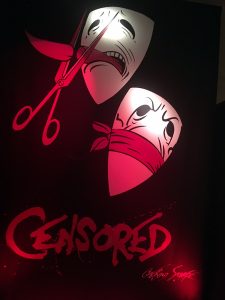

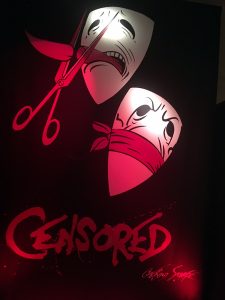

Censored by George Scarfe

Marking the 50th anniversary of the end of 300 years of theatre censorship, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition explores how restrictions on expression have changed.

The Theatres Act 1968 swept away the office of the Lord Chamberlain, which had the final say on what could appear on British stages.

“The 1968 Theatres Act was one of several landmark pieces of legislation in the 1960s, including the end of capital punishment, the legalisation of abortion, the introduction of pill, and the decriminalisation of homosexuality (for consenting males over the age of 21),” Harriet Reed, assistant curator at the V&A said.

Plays that had the potential to create immoral or anti-government feelings were banned by the Lord Chamberlain’s office or ordered to be edited. The exhibition includes original manuscripts with notes on what needs to be changed and letters from Lord Chamberlain explaining why the edits are required.

In the exhibition there are several pieces including a manuscript about the play Saved by Edward Bond. The play tells the story of a group of young people living in poverty and includes a scene in which a baby is stoned to death.

“When the Royal Court Theatre submitted the play to the censor, over 50 amendments were requested. Bond refused to cut two key scenes, stating ‘it was either the censor or me – and it was going to be the censor’. As a result, the play was banned,” Reed said.

Before the act was passed, playwrights got around the law by staging banned plays in “members clubs” which meant they could not be persecuted since it was private venue.

“The continued success of this strategy and the reluctance to prosecute made a mockery of the Lord Chamberlain’s powers and reflected the increasingly relaxed attitudes of the public towards ‘shocking’ material.

“The first night after the Act was introduced, the rock musical Hair opened on Shaftesbury Avenue in the West End. It featured drugs, anti-war messages and brief nudity, ushering in a new age of British theatre,” Reed said.

The exhibition changes from showcasing plays that were censored by the state to art, plays, movies, and music that are censored by society as a whole.

“It could be argued that a mixture of government intervention, funding/subsidy withdrawals, local authority and police intervention, self-censorship, and public protest now regulates what is seen on our stages,” she said.

Behzti, a play, and Exhibit B, a performance piece, were cancelled after protests by the public. The creators of both pieces were advised by the police to cancel their plays for health and safety reasons related to protests over the content.

Similarly, Homegrown, a play about radicalisation created by Muslims was shut down by the National Youth Theatre. The play was later published and a public reading was held.

On video, people involved in the UK arts industry such as Lyn Gardner, a theatre critic and Ian Christie, a film historian comment on what they believe to be censorship today. They cite art institutions that refuse to exhibit controversial material for fear of losing funding or facing public uproar. Julia Farrington, associate arts producer at Index on Censorship and one of the participants, calls this the “censorship of omission.”

The exhibition is capped by a piece by George Scarfe. The piece, the last work that attendees see, is a painting of two white masks on black cloth. The first one which is slightly higher and to the right of the second has it red tongue sticking out with the tip severed by a red scissors. The second one has a red cloth tied around it mouth. The word Censored is written in red and all caps below the two masks.

The painting is bold and the image of the tongue being cut off by scissors creates a “visceral” feeling. It depicts the two types of censorship that people now face– either talk and be violently censored or self-censor and never be heard.

“Many people would say that we are freer to express ourselves than ever before – with the boom of social media, we are able to communicate our thoughts and opinions on an unprecedented scale. This can also, however, invite more stringent and aggressive censorship from either the platform provider or under fear of criticism from other users,” Reed said.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index encourages an environment in which artists and arts organisations can challenge the status quo, speak out on sensitive issues and tackle taboos.

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534246236330-00e1ebeb-95f3-4″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]