27 Jan 2023 | Germany, Opinion, Poland, Ruth's blog

The theme of Holocaust Memorial Day this year is ordinary people. Words have power and their meaning changes with context – and in the context of the Holocaust the word ordinary is one that brings conflicted emotions. Those killed were indeed ordinary people who happened to be different, Jewish, gay, Roma, disabled, trade unionists and political dissenters. Many of those that killed them probably started as ordinary people who believed the propaganda that inspired hate and murder. Those that intervened to save them were ordinary people with an incredible value set that demanded in many cases that they risked their lives to save people that they barely knew.

In the run up to Holocaust Memorial Day I had the privilege of hearing the testimony of Janine Webber, a Holocaust survivor who lost huge swathes of her family. There is nothing quite so stark and shocking as hearing first-hand the stories of those people who were confronted with the ultimate evil. Janine survived the ghetto and was hidden and betrayed several times, eventually finding sanctuary in a convent and then with an elderly Polish family. She was saved by ordinary people and betrayed by ordinary people and before this happened to her she was an ordinary little girl in Poland. But in the course of four years she lost her parents, her brother and all of her extended family – the only other surviving members of her family were her aunt and an uncle. Her story will stay with me – and everyone else who heard her testimony – for as long as we live.

The question that has stuck with me since I had the privilege of listening to Janine, is what happens when she is sadly no longer with us. When the survivors are no longer with us to challenge those people who seek to deny or distort the facts of the Holocaust? The onus is on all of us to tell their stories and to shine a light on the lies and misinformation spouted by political extremists who seek to use one of the worst chapters in human history as a political football.

Last week the British House of Lords held its first debate to mark Holocaust Memorial Day. As a new member of the Lords, it was my privilege and responsibility to contribute to the debate. You can read my speech here.

Speaking about such an important topic in a national legislature is not something that anyone would or should take lightly, it was politics at its best – informed, considered and heartfelt.

The debate has made me think repeatedly about the fundamental importance of our core human rights and how we have to cherish and protect them. I can write this blog today because I have a guaranteed right, under British law, to express myself and articulate my opinions. Tyrants and dictators, always, as one of their earliest actions, seek to restrict a free media, undermine academic freedoms, remove books from libraries, and silence their critics. Index exists to provide a platform to those being silenced and we always will – but we also provide a voice to those who seek to tell truth to power, who seek to challenge misinformation, who stand against tyranny. We have for the last fifty years and we will for the next fifty.

27 Jan 2022 | Opinion, Politics and Society, Ruth's blog

Today is Holocaust Memorial Day, marking 77 years since the liberation of Auschwitz. Every year this is a day for reflection. To remember not just those that were murdered at the hands of the Nazis but also the trauma of those that survived and the impact on not just their families but on all of us in different ways.

I am a British Jewish woman, born 34 years after the end of the Second World War. My family had fled the Tsarist pogroms not the Nazis and had arrived in the UK in the 1890s. In theory the Holocaust, the Shoah, should be a horrible chapter in European history. Except it is more than that – it is an integral part of my identity and of our collective history. It has shaped my values, led me to campaign against political extremism, against neo-fascists of all ilks, it has made me wary of populist politicians and it has ultimately led me to Index – to be a voice for dissidents and those being persecuted.

In hindsight, this was because of my amazing mother. As a child Judaism for me was as much about cinnamon balls and chicken soup as it was about synagogue. I was raised in a very liberal and culturally Jewish home. Synagogue was for festivals, weddings and bar-mitzvahs. But when I was 11, I was staying at a friend’s house and her mum used an antisemitic trope. I didn’t really understand what she meant and why she was later so embarrassed which led to a long conversation with my mum.

My mum sat me down to explain what antisemitism was. This then led to a conversation about what had happened to our extended family in Eastern Europe during the war. She described the politics of Hitler and where they ended – of where hate can lead and our responsibilities to stand strong against it – no matter who it was directed at. And she finished by telling me that it didn’t matter whether I decided to be a practicing Jew or not – others (well the baddies) would always consider me a Jew, they would target me because of it and I needed to be prepared (how true that was!).

This led me to read – a lot. About the Holocaust, about Jewish life in Europe before the rise of Hitler. I read, I listened to testimony, and I was so lucky to meet survivors from the camps and to get to know some of the Kindertransport [children who were sent to the UK in order to survive]. I visited Auschwitz. I have cried for those that I never had the opportunity to meet and for the horror that the Holocaust brought to the world.

I was able to do this because of our free press and democracy. Because brave survivors have recorded their lived experiences for posterity. Because brave journalists reported on and filmed the camps during liberation. Because writers, artists and illustrators have worked tirelessly to ensure that the Shoah is not forgotten. To ensure that “Never Again” is not just a slogan.

This brings me to small county in Tennessee, McMinn County. Population 53,794. Earlier this month their school board unanimously voted to ban a cartoon book called Maus. Not only is it beyond my comprehension for a school board to believe it is appropriate to ban educational books but in this instance, it is beyond parody. Maus was written and illustrated by Art Spiegelman. It is the story of his parent’s experiences during the Holocaust. As a graphic novel it helps educate a new generation about the horrors of the Shoah. The human cost. You cannot tell the story of the Holocaust without challenging imagery and graphic depictions. The associated language is of course coarse. But how an earth can you expect to teach one of the most harrowing periods of human history without addressing what actually happened? And how can you believe that banning books, books about the Holocaust, when books were so famously banned, is an answer to any problem?

Education is the most important tool in our arsenal to make sure that the Shoah is never repeated. This is an affront.

Index is the UK lead on Banned Books Coalition – highlighting the absurdity of banning culture. We didn’t need any more examples of the irony of banning books – but if we did the school board in McMinn County have given us the most ludicrous example.

24 Feb 2016 | Academic Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Poland

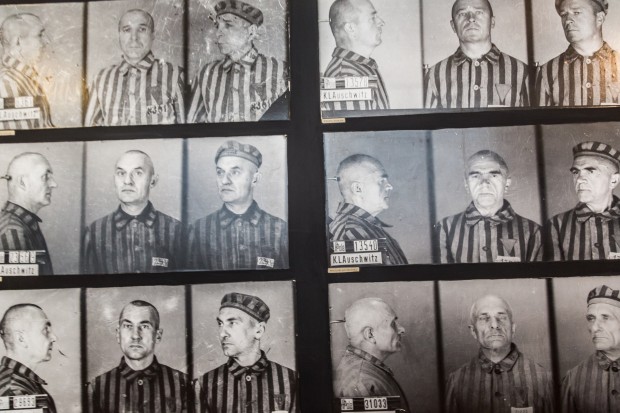

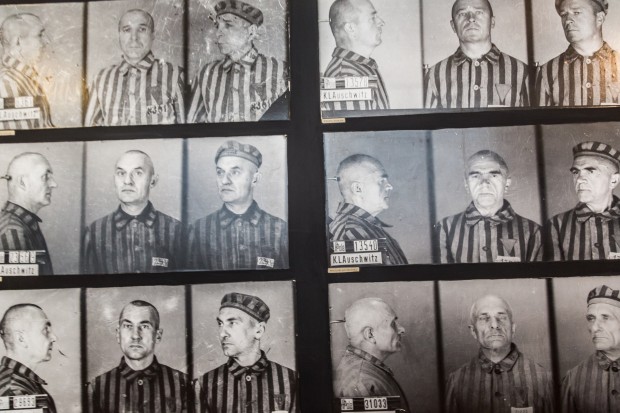

Still from an Auschwitz exhibition, 22 July 2014 in Oswiecim, Poland

When discussing academic freedom more than a century ago, German sociologist and philosopher Max Weber wrote: “The first task of a competent teacher is to teach his students to acknowledge inconvenient facts.” In Poland today, history appears to be an inconvenience for the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, which is introducing legislation to punish the use of the term “Polish death camps”.

The Polish justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro announced earlier this month that the use of the phrase in reference to wartime Nazi concentration camps in Poland could now be punishable with up to five years in prison. If enacted, Poland would find itself in the unique position of being a country where both denying and discussing the Holocaust could land you in trouble with the law. Holocaust denial has been outlawed in Poland — under punishment of three years “deprivation of liberty” — since 1998.

Any suggestion of Polish complicity in Nazi war crimes against Jews brings with it, in the party’s own words, a “humiliation of the Polish nation”.

Of course, Poland was an occupied country which suffered terribly under Nazi Germany, so any talk of acquiescence understandably hits a nerve. As all good history students know, however, the discipline has its ambiguities and competing theories, from the acclaimed to the crackpot, and singular, simplistic narratives are rare. But few democratic countries in the world punish those who argue unpopular historical positions. Which is why legislating against uneasy truths is the same as legislating against academic freedom.

Two recent examples show the Polish government of doing just this. Firstly, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda made public his serious consideration to stripping the Polish-American Princeton professor of history at Princeton University Jan Gross of an Order of Merit — which he received in 1996 both for activities as a dissident in communist Poland in the 1960s and for his scholarship — over his academic work on Polish anti-Semitism. Gross outlined in his 2001 book Neighbors that the massacre of some 1,600 Jews from the Polish village of Jedwabne in July 1941 was committed by Poles, not Nazis. More recently, the historian has claimed that Poles killed more Jews than they did Germans during the war, which prompted the current action against him.

Some who disagree with his arguments have labelled Gross an “enemy” of Poland and a “traitor to the motherland”. The historian has hit back, saying in an interview with the Associated Press: “They want to take [the Order of Merit] away from me for saying what a right-wing, nationalist, xenophobic segment of the population refuses to recognise as facts of history.”

Academics too — Polish and otherwise — have come to his defence. Agata Bielik-Robson, professor of Jewish Studies at Nottingham University, points out that a “democracy has to have a voice of inner criticism”. She is worried that PiS is seeking to do away with such criticism in order “to produce a uniform historical perspective”.

Polish journalist and former activist in the anti-communist Polish trade union Solidarity Konstanty Gebert explained to Index on Censorship that PiS has made “convenient scapegoats” of people like Gross. “PiS is moving fast to reestablish a ‘positive narrative of Polish history’ by breaking with an alleged ‘pedagogy of shame’,” he said.

The party first tried — unsuccessfully — to outlaw the term “Polish death camps” in 2013 when it was in opposition. Should the law now pass, and you need help adhering to the proposed rules, the Auschwitz Museum has released an app to correct any “memory errors” you may experience. It detects thought crimes such as the words “Polish concentration camp” in 16 different languages on your computer, keeping you on the right track with prompts asking if you instead meant to write “German concentration camp”.

Poland may have lurched to the right with the election of PiS last October, but the party’s authoritarianism — from crackdowns on the media to moves to take control of the supreme court — seems positively Soviet in some respects. Attempts to control history, too hark back to the Polish People’s Republic of 1945-1989, when, in the words of Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier in the winter 1985 issue of Slavic Review, “cultural patterns” and “habits of mind” made it impossible to make historical interpretations “alien to that national sense of identity and a methodology at odds with the canons and objective scholarship”.

Gebert sees similarities between current and communist-era propaganda “in the basic formulation that there is nothing to be ashamed of in Polish history, and in Polish-Jewish relations in particular, and in the belief that there is one correct national viewpoint”.

However, now that freedom of speech exists, the government can and are being criticised for their actions. “This puts the government propaganda machine on the defensive,” Gebert said.

Just last week, President Duda spoke against the “defamation” of the Polish people “through the hypocrisy of history and the creation of facts that never took place”. He has made his motives clear: “Today, our great responsibility to create a framework […] with the dual aim of fostering a greater sense of patriotic pride at home while enhancing the country’s image abroad.”

It should be intolerable for the freedoms of any academic subject to be impinged for ideological ends. If academic freedom is to mean anything, it should include the right to tell uneasy truths, get things wrong and have you work challenged by the highest academic standards.

There’s only one place to turn for PiS to find an example of best practice on how to challenge Gross’ research, and that is to the very body the party will grant authority to on deciding on what is and isn’t a breach of the law regarding “Polish death camps”. Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) produced several reports between 2000-03 challenging claims in Gross’ book on the Jedwabne massacre. It used research and reason — as opposed to censorship — to make the case that the historian didn’t get all the facts right. It found, for example, that German’s played a bigger part in the slaughter than Gross had claimed, and that the numbers killed were more likely to be around the 340 mark, rather than 1,600.

IPN should tread carefully, though. Any inconvenient truths with the potential to humiliate the Polish people could one day soon see it branded a “traitor”.

Ryan McChrystal is the assistant editor, online at Index on Censorship