Banned Books Week 2022: In conversation with Xinran

Xinran has dedicated her career to highlighting the stories of Chinese people – and in particular Chinese women – set against the backdrop of an ever-changing political landscape. She started her career as the host of a call-in radio programme entitled “Words on the Night Breeze” which mainly focused on women’s stories. She has since gone on to publish nine books which have been translated into more than 40 languages.

Her writing focuses on Chinese realities in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. China Witness: Voices from a Silent Generation (2008) gives first-hand accounts of historical events in an attempt to counteract the destruction of historical documents during the Cultural Revolution. Her most recent release The Promise: Tales of Love and Loss in Modern China (2019) follows Chinese women through four generations.

Xinran has both experienced and observed censorship. And she highlights the ways in which Chinese censorship has changed over time with the introduction of new technologies and changing political dynamics.

The theme for Banned Books Week 2022 is “Books Unite Us. Censorship Divides Us.” Banned Books Week is an annual event celebrating the freedom to read. The initiative was launched in 1982 in response to a sudden surge in the number of challenges to books in schools, bookshops and libraries in the United States. Throughout the week, partner organisations come together to highlight the value of free and open access to information. We unite in shared support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular. XINRAN’S READING LIST

Xinran has also shared this reading list for those who want to learn more about the current realities in mainland China.

Feng Jicai

Born in Tianjin in 1942, Feng Jicai is a contemporary author, artist and cultural scholar who rose to prominence as a pioneer of China’s Scar Literature movement that emerged after the Cultural Revolution.

Yu Hua

Yu Hua grew up during the Cultural Revolution and this is a recurring topic in his writing. His writing often includes detailed descriptions of violence. Yu Hua’s most prominent novels include Chronicle of a Blood Merchant and To Live. The latter was adapted for film by Zhang Yimou but it was subsequently banned in China. Adding to this, his nonfiction collection, China in Ten Words (2010), cannot be distributed legally in mainland China because of its edgy political content.

Feng Tang

Through novels and poetry, Feng Tang describes life in contemporary Beijing. is best known for his novels Trilogy of Beijing (2021) and Oneness (2011). The latter explores the interplay between sexuality and religion.

Fan Wu

Fan Wu is a Chinese-American novelist and short story writer. She writes about China as well as Chinese immigrants in the US, with a focus on female characters. Her debut novel titled February Flowers (2007) is set on a Chinese college campus.

Banning books is a weak act

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

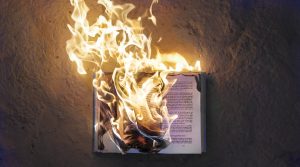

Book burning, photo: Fred Kearney

It seems surreal that in the 21st century in Europe and in the US, we still have to make the argument for a free press and public access to literature. But since 1982 an international coalition against censorship has had to make exactly that case.

I find the concept of banned books chilling. Why would you seek to ban or destroy literature, culture and history? Why would you seek to remove arguments you disagree with rather than challenge them and prove that you are right? Banning books is a weak act – done by those who know that their arguments are easily defeated. But is this level of control and repression which scares me – we know where it can lead.

Of all the touching and heart-breaking Holocaust memorials in Berlin, it is the Empty Library that made me stop – a visual representation of what book burning is and what happens when intolerance is allowed to dominate. On 10 May 1933 20,000 books were burned – their authors were Jews, Communists and Socialists – 40,000 people crowded the Bebelplatz to watch them burn.

This is where banning books can lead. This is the ultimate reality of censorship and intolerance.

Occasionally I am asked why free speech is so important to me. Why is this even important anymore in the age of the internet and nearly unfettered access to the accumulated knowledge of the world for those of us lucky enough to live in liberal democracies. But this is why I fight for free expression, for tolerance, for knowledge, for debate. This is why I work at Index on Censorship. I don’t have to agree with an author to defend their right to publish. I don’t have to like a book to defend its right to be in a library and I don’t have to delete works that I fundamentally oppose.

Which brings us to Banned Book Week. Every year, in fact nearly every day, there are reports of libraries removing books or authors being challenged – not necessarily for their published works but on occasion for their views. The American Library Association publishes an annual list of the most challenged books in the US:

- George by Alex Gino. Challenged, banned, and restricted for LGBTQIA+ content, conflicting with a religious viewpoint, and not reflecting “the values of our community”.

- Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds. Banned and challenged because of the author’s public statements and because of claims that the book contains “selective storytelling incidents” and does not encompass racism against all people.

- All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. Banned and challenged for profanity, drug use, and alcoholism and because it was thought to promote antipolice views, contain divisive topics, and be “too much of a sensitive matter right now”.

- Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson. Banned, challenged, and restricted because it was thought to contain a political viewpoint, it was claimed to be biased against male students, and it included rape and profanity.

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie. Banned and challenged for profanity, sexual references, and allegations of sexual misconduct on the part of the author.

- Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story about Racial Injustice by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard, illustrated by Jennifer Zivoin. Challenged for “divisive language” and because it was thought to promote antipolice views.

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee. Banned and challenged for racial slurs and their negative effect on students, featuring a “white saviour” character, and its perception of the Black experience.

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck. Banned and challenged for racial slurs and racist stereotypes and their negative effect on students.

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. Banned and challenged because it was considered sexually explicit and depicts child sexual abuse.

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas. Challenged for profanity, and because it was thought to promote an antipolice message.

These are not the only banned works we know of but it gives us all a flavour of the debate that is occurring across our liberal democracies and makes it clear of the work we still have to do. Of course, it isn’t just literature that is challenged or banned – but poetry and arts continue to be censored. Which is why, in partnership with the British Library. we held an event to mark Banned Books Week exploring poetry and protest – with Dr Choman Hardi and ko ko thett, chaired by Index on Censorship’s vice chair Kate Maltby. You can watch the event on catch-up here.

So, as we collective mark Banned Books week – I urge you – go into a bookshop or a library and get a book that challenges you, that inspires you and one that others seek to ban![/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

What you missed from Banned Books Week 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115172″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Books have long been objects of contention, criticised for spreading ideas which go against the status quo. They are removed from libraries and bookshops, burned, banned and vandalised while writers are attacked, threatened, imprisoned. These actions are nothing new, yet the importance of preserving our freedom to read is more important now than ever.

Freedom to read is at the centre of Banned Books Week, an initiative which has sought to challenge censorship on both sides of the Atlantic, bringing together literary communities – librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers – in shared support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.

The initiative was launched in the USA in 1982 in response to a surge in the number of challenges to books in schools. Since then, it has sought to highlight the value of free and open access to information. Each year sees an exciting strand of events, readings list, games and activities designed to get people thinking about books that have been banned throughout history, and are still causing offense today.

As the 2020 Banned Books Week comes to a close, we have a chance to reflect on the impact the initiative has had over the past 38 years, and consider the work we still need to do to ensure everyone is free to read.

Censoring literature is nothing new. It has a long and dark history and has been exercised by governments, political parties and religious groups for centuries. Book burning, which has been recorded as early as the 7th century BCE, and proliferated under the Nazi party in Germany in 1933, is emblematic of a harsh and oppressive regime which is seeking to censor or silence some aspect of prevailing culture.

Today’s methods of censorship remain prevalent yet differ in style. Political leaders use legal methods to silence or prohibit writing which paints themselves and their parties in an unpleasant light – techniques not so different to the vexatious lawsuits used to silence journalists. Academic textbooks are rewritten to paint recent historical events in a very different light, and a favourite illustrated bear has long been banned to protect the ego of other fragile leaders.

As well as these more blatant signs of government censorship, literature is still challenged today. Some of the most canonical works of the 20th century have famously been challenged – including The Handmaid’s Tale, Animal Farm and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which this year sees the 60th anniversary of its uncensored publication in the UK. But it is children’s books that cause a particular stir, such as And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell which tells the true story of two male penguins who create a family together and was subsequently banned in US schools and libraries for depicting same-sex marriage and adoption.

While this year’s Banned Books Week took a different shape from previous years, we had the pleasure of hearing a number of writers speak about their experiences of being silenced, censored or simply refused a platform. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the resultant global Black Lives Matter protests, it has been clearer than ever before that the voices of some are prioritised to the exclusion of others.

In an online session on 29 September, Urvashi Butalia spoke to poet Rachel Long, and authors Elif Shafak and Jacqueline Woodson about what ‘freedom’ means in the culture of traditional publishing, and how writers today can change the future of literature. During the event, Shafak defended freedom of speech and spoke about her experience of seeing her works of fiction brought into the courtroom – “it was very surreal to me. Art needs freedom, even though it may be harmful in the eyes of authorities.”

Shafak’s comments harked back to those made by Nobel laureate Toni Morrison during the launch of the Free Speech Leadership Council, an advocacy arm of the National Coalition Against Censorship. At the event, Morrison spoke of her novel Song of Solomon being banned at a prison after the warden expressed fear that it might stir the incarcerated to riot. An acoustical lapse led Morrison to speculate as to whether the real fear was of the inmates incitement to “riot” or “write” – asking, which would ultimately be the most dangerous?

While authorities and governments fear literary works that are seen to challenge them, we are reminded this Banned Books Week of the importance of free artistic expression and of literature’s power to challenge even the most powerful, oppressive forces. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]