11 Jan 2014 | Burma, China, Digital Freedom, Gambia, News and features

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Facebook has nearly 1.2 billion monthly active users –that’s nearly 20% of the total global population. Yet, in some countries harsh sanctions and time in jail can be imposed on those who comment on social media, in the majority of cases for speaking out against their government.

China

China is infamous for its stance on censorship but September 2013 saw the introduction of perhaps one of their more bizarre laws: post a message online that the government deems defamatory or false and if it receives more than 500 retweets (or shares) or 5,000 views and the person responsible for the post could receive up to three years in jail.

For the post to be of concern to the government it must meet certain criteria before a conviction can occur. This includes causing a mass incident, disturbing public order, inciting ethnic and religious conflicts, and damaging the state’s image. And to top that off the post could also be a “serious case” of spreading rumours or false information online.

According to the Guardian one Weibo user, China’s largest microblogging site, wrote: “”It’s far too easy for something to be reposted 500 times or get 5,000 views. Who is going to dare say anything now?” whilst another claimed: “This interpretation is against the constitution and is robbing people of their freedom of speech”.

Vietnam

Decree 72 came into effect in Vietnam this year, a piece of legislation which makes it a criminal offence to share news articles or information gathered from government sites over online blogs and social media sites. The new law was criticised globally when it was announced in September as the latest attack on free expression in Vietnam adds to the list of censorship tactics already in place in the country; websites covering religion, human rights and politics have been blocked along with social media networks and some instant messaging services.

There are also fears that Decree 72 will risk harming international relations, with a direct impact on Vietnam’s economy, as well as internal restraints on the development of local businesses. Marie Harf, Deputy Spokesperson for the U.S. Department of State, said in a press statement: “An open and free Internet is a necessity for a fully functioning modern economy; regulations such as Decree 72 that limit openness and freedom deprive innovators and businesses of the full set of tools required to compete in today’s global economy.”

Burma

Going to jail merely for receiving an email would seem absurd to much of the world. In Burma this is written into law.The Electronic Transactions Law 2004 allows imprisonment of up to 15 years for “acts by using electronic transactions technology” deemed “detrimental to the security of the State or prevalence of law and order or community peace and tranquillity or national solidarity or national economy or national culture”. Put into layman’s terms that could mean a hefty jail sentence for being on the receiving end of an email the government isn’t so fond of.

Despite talks to remove the lengthy jail terms many feel the changes don’t do enough to tackle a problem with censorship the country has faced for several decades.

Gambia

Those who intend to critics the Gambian government online should only do so if they have a stack of money to spare, $82,000 to be precise, or be willing to spend 15 years in jail. Under the recently passed Information and Communication (Amendment) Act anyone accused of spreading “false news” about the government or public officials online will face these heavy sanctions. Other ways in which Gambians can find themselves behind bars includes producing caricatures or making derogatory statements against public officials online, inciting dissatisfaction via internet posts or instigating violence against the government online.

Article 19 condemned the Act, criticising it for being “a flagrant breach of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), as well as the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), both of which Gambia is a party to”.

This article was posted on 11 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Apr 2013 | United Kingdom

Are you passionate about freedom of expression? Do you want to write for an award-winning, internationally renowned magazine and website, which has published the works of Aung San Suu Kyi, Salman Rushdie and Arthur Miller? Then enter Index on Censorship’s student blogging competition!

The winning entry will be published in Index on Censorship magazine, a celebrated, agenda-setting international affairs publication. It will be posted on our popular and influential website, which attracts contributors and readers from around the world. Index is one of the leading international go-to sources for hard-hitting coverage of the biggest threats and challenges to freedom of expression today. This competition is a fantastic opportunity for any aspiring writer to reach a global, diverse and informed audience.

The winner will also be awarded £100, be invited to attend the launch party of our latest magazine in London, get to network with leading figures from international media and human rights organisations, and will receive a one-year subscription to Index on Censorship magazine.

To be in with a chance of winning, send your thoughts on the vital human right that guides our work across the world, from the UK to Brazil to Azerbaijan. Write a 500-word blog post on the following topic:

“What is the biggest challenge facing freedom of expression in the world today?

This can cover old-fashioned repression, threats to digital freedom, religious clampdown or barriers to access to freedom of expression, focusing on any region or country around the world.”

The competition is open to all first year undergraduate students in the UK, and the winning entry will be determined by a panel of distinguished judges including Index Chair Jonathan Dimbleby. To enter, submit your blog post to [email protected] by 31 May 2013.

24 May 2012 | Middle East and North Africa, Uncategorized

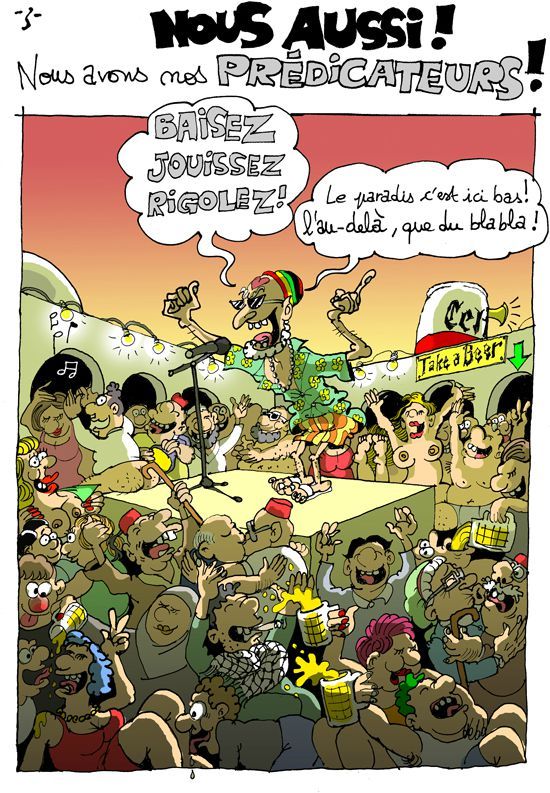

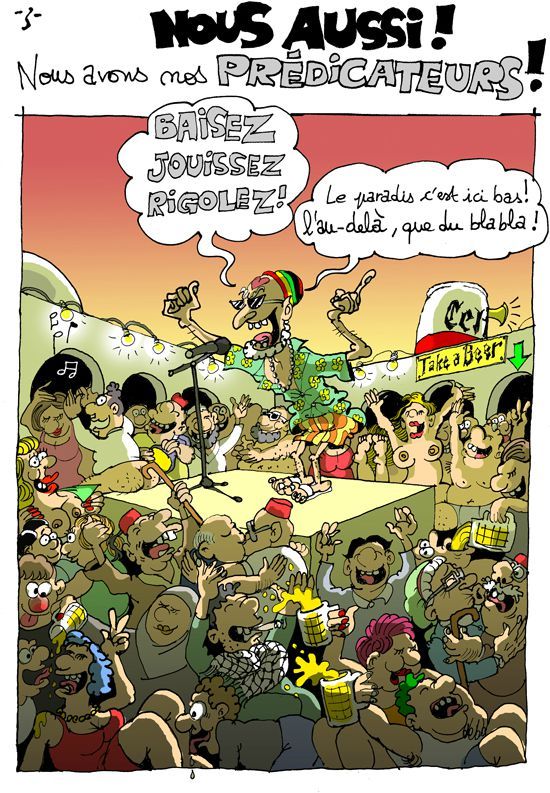

Anonymous renowned Tunisian caricaturist _Z_ is under fire. His bold caricaturist style, no stranger to his fans, has landed him in trouble.

For years, his caricatures mocked Ben Ali’s autocratic and corrupt regime. The regime censored his caricatures, but did not succeed in tracking him down and exposing his identity. In 2009, police arrested blogger Fatma Riahi, and accused her of being behind _Z_.

More than 18 months after the fall of the regime, _Z_ still desires to conceal his identity. His caricatures now target the Islamists of Tunisia. _Z_ knows no boundaries, no red lines. For him anything can be caricatured and ridiculed. Something, many in Tunisia will not like, especially when it comes to what they consider as “sacred”, and “immoral”.

On 18 May, Facebook removed two cartoons by _Z_ following complaints the social networking site received. The cartoonist wrote about the decision on his blog the same day:

“Two caricatures published on my Facebook page DEBA Tunisie have just been censored. Each caricature contains little bit of sex, little bit of politics, and little bit of religion. There will always be an orthodox Tunisian who would snivel about them [caricatures] to Zuckerberg. My friends, according to our morality guardians there is inevitably a boundary that should not be crossed when it comes to tackling the Saint Trinity of the three Tunisian taboos: politics, sex, and God”

One of _Z_’s censored caricatures ridicules the members of Tunisia’s constitutional assembly, showing them taking part in various distracting activities during a meeting, apart from actually drafting the country’s constitution. Two MPs are shown having anal sex, and others are shown masturbating, playing chess and gambling. Another shows a lively party where a “cleric” says: “have sex, enjoy, and have fun. Paradise is down here. Up there is only bla bla bla!”

Some of _Z_’s caricatures also depict god and Prophet Muhammad, considered to be forbidden in Sunni Islam, leading to the launch of a fierce social media campaign against the artist. Tunisian journalist Thameur Mekki, believed by some to be the anonymous artist, has been the target of death threats meant for _Z_.

Both _Z_ and Mekki have denied these allegations. Mekki told Mag14.com that “this is a murder incitement matter” and said he would “lodge a complaint against those who are disseminating lies”.

25 Jan 2012 | Leveson Inquiry

Blogger and media lawyer David Allen Green has praised social media at the Leveson Inquiry today.

Green, legal commentator at the New Statesman, argued that bloggers and Twitter users should not be viewed as “rogues”, adding that social media users often act responsibly and regulate themselves by being transparent.

“Most alleged abuses by people using social media can often be traced back to someone who may or may not have an agenda,” he said.

He added it was “wonderful” that mainstream sources were co-operating with social media users, noting that “almost every journalist now has a Twitter account” and that the platform is increasingly used to distribute breaking information quickly.

Revealing he has made about “about £12” from advertisements on his Jack of Kent blog, Green told Lord Justice Leveson bloggers do not blog for the money but to “engage in public debate…[and] be part of a civic society.”

He claimed the mainstream media’s use of photographs from social media sites such as Facebook was “analogous” to the phone-hacking scandal, noting that newspapers do it “routinely” without recognising that it is a form of copyright infringement.

The editor-in-chief of the Press Association, Jonathan Grun, also appeared today. He said the news agency, which provides a “constant stream” of stories and video to major British news organisations, placed great emphasis on accuracy, adding that its customers needed to be able to rely on it without making checks.

He said most editorial mistakes occur “by accident”. He described one occasion in which a PA reporter with 30 years of experience confused someone named in a story with another person of the same name. Grun said it was the agency’s “gravest editorial error”, adding that the reporter was so ashamed that they resigned.

There will be a directions hearing for Module 2 of the Inquiry, which will examine the relationships between the press and police, later this afternoon.

Hearings continue tomorrow, with evidence from representatives from Facebook and Google, the Information Commissioner’s Office and journalist Camilla Wright.

Follow Index on Censorship’s coverage of the Leveson Inquiry on Twitter – @IndexLeveson