13 Feb 2014 | News, Religion and Culture, Turkey

Limitations and challenges to freedom of expression and of assembly in Turkey have – once again – come to international attention over the past year. But despite this, censorship of the arts is often under-reported.

Siyah Bant was founded in 2011 as a research platform that documents censorship in the arts across Turkey by a group of arts managers, arts writers and academics working on freedom of expression. The group is concerned that many instances of censorship in the art world, especially in the visual and performing arts, were under-reported and only circulated as anecdotes. Siyah Bant also found the blanket understanding that “it is the state that censors” to be insufficient.

The Gezi Park protests that began in late May 2013 not only highlighted the continued existence of police violence and the institutionalized use of excessive force that has long been a familiar sight in the Kurdish region, and, more recently, in the protests against hydroelectric plants in the Black Sea parts of Turkey. The demonstrations also made apparent the tight grip that the alliance of political establishment and business conglomerates have over Turkish print and broadcasting media, as numerous journalists were fired for reporting on the anti-government protests.

Together with China and Iran, Turkey has been taken the lead in terms of numbers of imprisoned journalists, many of which are charged under anti-terrorism laws. Currently, all eyes are on the amendments to internet law 5651 that passed parliament in early February 2014, now waiting to be signed into effect by President Abdullah Gül.

While the government claims these changes are to ensure privacy and clamp down on pornography, activists maintain that the law will procedurally ease the profiling of internet users and effectively heighten government control over online content. Turkey has already a questionable track record when it comes to internet freedom with access to more than 40,000 internet sites being restricted.

Rather than operating through bans and efforts at complete suppression that marked the 1980 coup d’état and its aftermath, the current censorship mechanisms in Turkey aim to delegitimize and discourage artistic expressions and their circulation.

Siyah Bant’s initial aim was two-fold: Firstly, the group conducted research in five cities to identify and examine different modalities of censorship and the actors involved in censoring motions. Secondly, Siyah Bant wanted to create awareness around censorship in the arts and facilitate solidarity networks in the advocacy for freedom of expression in the arts.

In the course of its research it set up a website that documents arts censorship in Turkey and assembled two publications. The first presents selected case studies of censorship in the arts in Turkey as well as international initiatives in the fight for freedom of expression. The second focuses more closely on artists’ rights and the legal framework of freedom of the arts in Turkey as well as the ways in which these laws are applied–or not applied, in most cases.

The reports below center on new developments in Turkish cultural policy and their effects on freedom of arts as well as interviews conducted in Diyabakir and Batman where artists engaged in the Kurdish rights struggle have long been subjected to differential treatment by the Turkish authorities. Research for these reports was supported by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

• Developments in cultural policy and its effects on freedom of the arts, Ankara

• Artists engaged in Kurdish rights struggle face limits on free expression

This article was published on 13 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

7 Feb 2014 | News, United Kingdom

Journalist Jane Fae

Feminist writer Jane Fae says she has been stopped from opening a bank account for her new project – a history of the censorship of pornography.

Fae, a contributor to Index on Censorship, had agreed with NatWest bank to set up a business account to handle the incomes and outgoings for her new self-published book, Taming the Beast.

But according to a blog post today, Fae says the bank contacted her this morning (7 February) and reneged on the agreement.

Blogging at Faeinterrupted, the journalist, who has written for outlets from the Guardian to the Daily Mail (as well as this site) reported that she had gone through all the normal procedures with the bank and signed up for a new account. She goes on:

Then, this morning, out of the blue, the call. She had since run it past her boss…her manager.

Who was less impressed. “NatWest don’t do this sort of thing”, she explained.

“Er, what sort of thing? Publishing? Academic work?”

“No: the subject matter”.

I was incredulous. “You mean that NatWest will not sanction someone writing ABOUT a particular topic? Are there any other topics you’d rather people not write about in case, you know, in case it frightens the admin staff? Perhaps we had better not write about rape, or vioilence against women or…”.

Who knows.”

Fae is waiting for a proper explanation from NatWest.

A spokeswoman for the bank told Index the issue was being investigated

Index on Censorship will keep you up to date with developments.

UPDATE 07/01/14 16:05. A NatWest spokeswoman has been in touch with Index to tell us that the business manager of the branch in Stamford, Lincolnshire is arranging to meet Jane Fae next week. The bank says “the issue is not closed”.

7 Feb 2014 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 43.01 Spring 2014

[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”55789″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2014/03/carnage-clyde-wwii-cover/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

When the small Scottish shipbuilding town of Clydebank was flattened during one of the most destructive bombing raids of World War II, officials took extraordinary measures to suppress the details. John MacLeod reports for the spring 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

On a moonlit evening on Thursday 13 March 1941, just after 9pm, the first of 236 German bombers converged on Clydeside. By 9.10pm, over the western suburbs of Glasgow, over Bowling and Dalnottar and – especially – over the crowded, densely housed and productive little town of Clydebank, the bombs had begun to fall. And the next night, it happened all over again.

Read the full article.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”90659″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://shop.exacteditions.com/gb/index-on-censorship”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine on your Apple, Android or desktop device for just £17.99 a year. You’ll get access to the latest thought-provoking and award-winning issues of the magazine PLUS ten years of archived issues, including The war of the words.

Subscribe now.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Jan 2014 | Egypt, News, Politics and Society

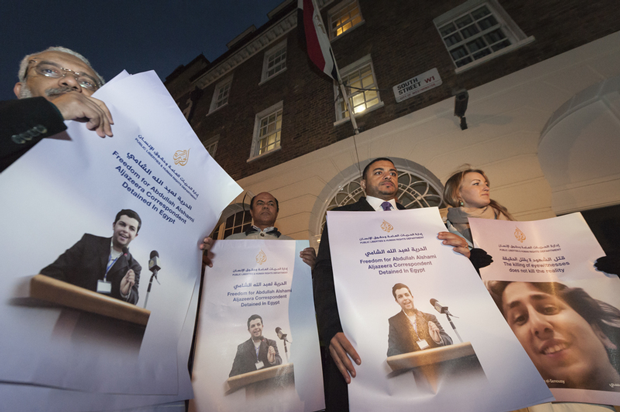

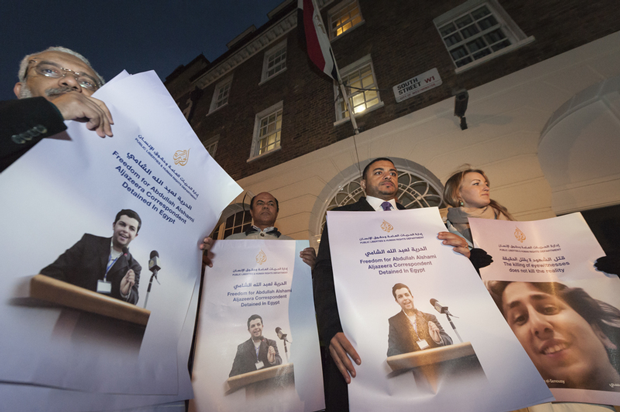

In November 2013, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ UK and Ireland), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and the Aljazeera Media Network organised a show of solidarity for the journalists who have been detained, injured or killed in Egypt. (Photo: Lee Thomas / Demotix)

In a new sign of a regression in press freedom in Egypt, authorities have ordered three journalists working for the Al Jazeera English (AJE) channel held in custody for fifteen days.

The journalists –AJE Cairo Bureau Chief Mohamed Fadel Fahmy, award-winning former BBC Correspondent Peter Greste and producer Baher Mohamed–were arrested in a police raid on Sunday on a makeshift studio at a luxury Cairo hotel. They were charged with “belonging to a terrorist group and broadcasting false news that harms national security .”

Cameras and other broadcasting equipment were seized during the raid on the work room where the AJE TV crew had reportedly conducted interviews with activists and Muslim Brotherhood members on the political crisis in Egypt. A fourth member of the AJE team–Cameraman Mohamed Fawzy–was also arrested but was released hours later without charge.

The latest detentions raise the number of journalists affiliated with Al Jazeera and who are now jailed in Cairo , to five. Al Jazeera Arabic correspondent Abdullah Al Shami was arrested on 14 August while covering the brutal security crackdown on supporters of toppled President Mohamed Morsi at Rab’aa–the larger of two encampments where pro-Morsi protesters had been demonstrating against his forced removal and demanding his reinstatement. Al Jazeera Mubasher Misr Cameraman Mohamed Badr was meanwhile, arrested on 15 July while covering clashes between security forces and pro-Morsi protesters in Ramses Square.

Al Jazeera has denounced the arrests of its staff members as an act designed to “stifle and repress the freedom of reporting by the network’s journalists.” The Egyptian government’s hostility towards journalists affiliated with the Qatari-based network has been prompted by what many Egyptians perceive as “a pro-Muslim Brotherhood bias in the network’s coverage of the events unfolding in Egypt”. Since the military takeover of the country in July 2013, at least 22 staff members have resigned from AJ Jazeera Mubasher Misr, the Egyptian arm of the network , over the alleged “bias in favour of the Islamist group”. Al Jazeera has however, denied the allegation.

The latest detentions are perceived by analysts as part of the crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood–the Islamist group from which the deposed President hails. Last week, the group was officially classified as a “terrorist organization” by the Egyptian authorities, in a move criminalizing the group’s activities, financing and membership .

The arrests of the AJE journalists have also raised fears among rights activists and organizations that the government crackdown was “widening to silence all voices of dissent”. Human Rights Lawyer Ragia Omran told the New York Times on Monday the charges are “part of a pattern of aggressive prosecutions–including conviction of protesters— that were rarely pursued even under Hosni Mubarak.” The New York-based Committee For the Protection of Journalists , CPJ, has also condemned the arrests, calling on the Egyptian government to release the journalists immediately . In a statement released by CPJ, Sherif Mansour, Middle East and North Africa coordinator , said ” the Egyptian government was equating legitimate journalistic work with acts of terrorism in an effort to censor critical news coverage.” In its annual census conducted last month, the CPJ ranked Egypt among the top ten jailers of journalists in the world with at least five journalists languishing in Egyptian prisons. It has also listed Egypt among the three most dangerous countries for journalists in the Middle East after Syria and Iraq . Six journalists have been killed in the country over the course of the past year, three of them while covering the bloody crackdown on Morsi’s supporters at Rab’aa.

Members of Mohamed Fahmy’s family meanwhile used his Twitter account to send a message on Tuesday reminding the government that “journalists are not terrorists.” His supporters meanwhile started a hashtag on Twitter calling for his release. Many of them expressed disappointment at what they described as “the government’s latest act of repression” warning that it would harm the government’s image much more than any amount of critical reporting would.

This article was posted on 2 Jan 2013 at indexoncensorship.org