26 Jun 2018 | Artistic Freedom, India, News and features

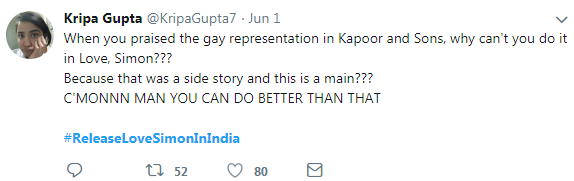

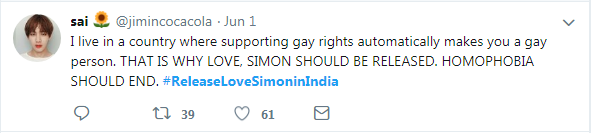

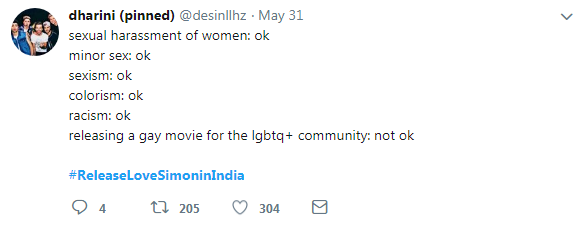

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”101140″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Indians took to Twitter to express their frustration after the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) pushed the release of the film Love, Simon back indefinitely.

Originally slated to be released on 1 June, Love, Simon was eagerly awaited by some Indian moviegoers, who attempted to purchase advance tickets only to be denied. Soon after the hashtag #ReleaseLoveSimoninIndia began trending.

Love, Simon is a film based on the book Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda written by Becky Albertalli in 2015. Simon is a 17-year old boy in high school who despite having close, loving and supportive relationships with his friends and family keeps his homosexual identity a secret from them. This is the first major gay romantic comedy film to be released by a major US studio. Fox 2000 rolled it out in the US, where the movie had a favourable response from both critics and movie-goers.

According to an anonymous source cited by The Free Press India, the CBFC decided against allowing the film to be shown because there is “no audience” for it. This assertion flies in the face of the film’s worldwide success and vocal supporters within India.

“I doubt that it can be said that the film has “no interest” but rather it has less popularity than other mainstream foreign movies, the reason being India is deeply homophobic but I don’t think that justifies not releasing it,” Ruth Chawngthu, the digital editor at Feminism in India and co-founder of Nazariya LGBT, told Index on Censorship via email. “I could be wrong but to my knowledge the film creators decided to not release it so perhaps the concerned persons should petition them instead? I personally don’t have strong feelings regarding the issue because it’s mostly the privileged upper class who are concerned about it. They were focused on the movie while ignoring the fact that members of the LGBT community were facing violence in different parts of the country at the same time.”

The CBFC states that it stands in the way of “[moral] corruption [as social depravity] has been one of the major obstacles to economic, political and social progress of [India].” This is in relation to Penal Code 377, a leftover from the Victorian era when India was a part of the British empire, and has yet to be changed due to social anxiety around the LBGT+ community. While India is in the process of reconsidering its 377 Penal Code which criminalizes “unnatural relations with man, women, and animal”, the diverse traditional religious communities within India and social stigma hold back public opinion.

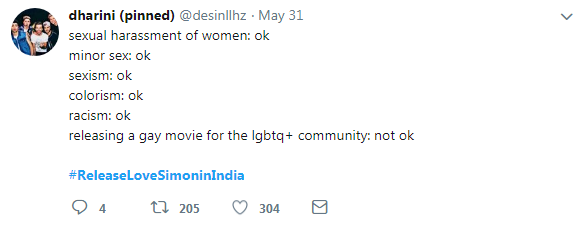

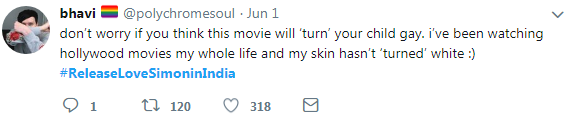

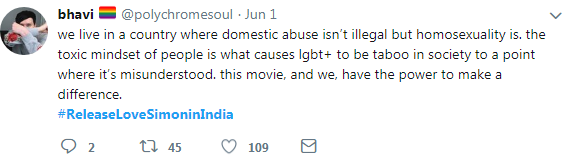

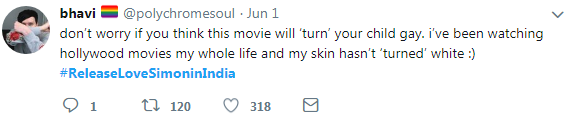

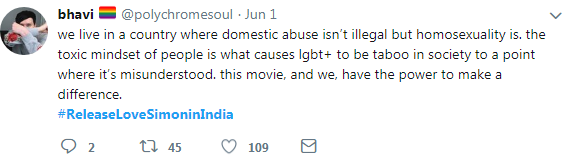

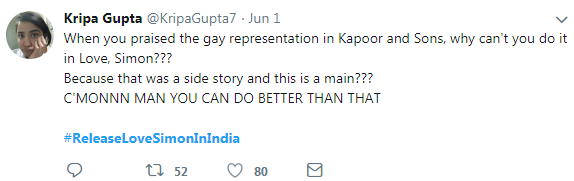

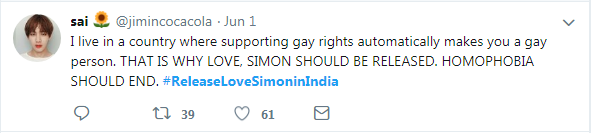

Indians took to Twitter to express their opinions on the indefinite delay on Love, Simon’s release: [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Politicians such as Rajya Sabha MP and BJP leader Subramanian Swamy feel justified in delaying the release of the film to “protect the culture of India”. Twitter users raved that Love, Simon would have been a landmark film that would humanize the LBGT+ community in India. However, at the tail end of International Pride Month, the film has still yet to be released. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Politicians such as Rajya Sabha MP and BJP leader Subramanian Swamy feel justified in delaying the release of the film to “protect the culture of India”. Twitter users raved that Love, Simon would have been a landmark film that would humanize the LBGT+ community in India. However, at the tail end of International Pride Month, the film has still yet to be released. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Jan 2014 | India, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

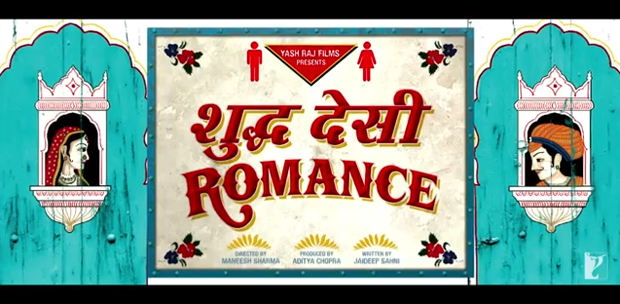

(Image: YRF/YouTube)

It an interesting introduction to his modus operandi, the new CEO of India’s censor board has described his objection to some of India’s recent blockbusters is based on the reactions of his wife and five year old daughter.

In an interview to the Mumbai Mirror, Rakesh Kumar, was quoted as saying: “After watching Shudh Desi Romance, my five-year-old daughter asked me, ‘Dad, isn’t there too much love in this movie?’ More recently, I went to see Yaariyan with her and came out visibly embarrassed. Now, I have decided not to see even a UA film with my kid.”

Predictably, reactions were fierce. Movies with a UA rating in India are tagged for parental guidance, as they might be inappropriate for young children. These movies have mild sex scenes, gory images of violence and crude language. Kumar, a former employee of the Indian Railways, might feel “inappropriate content” is making it to the big screens, however, it only serves to highlight that the censorship of movies cannot be viewed from the perspective of a five year old girl.

Aside from the many jokes being made at Kumar’s expense, a deeper issue has been brought to the surface yet again. A constitutionally mandated body under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) regulates any films that are to be publicly exhibited. In India, there are a number of certificates a film could be given: A for Adult, UA, unrestricted public exhibition with parental guidance, S, restricted to a special class of persons, and the coveted U, which is unrestricted public exhibition, and is also the class of movies that can be shown on Indian television at prime time.

The first question many might ask is, does India need a censor board? With all kinds of content available on television and the internet, is censoring film for “inappropriate” content still valid? However, given that India does have a censor board, the next question is who it is made up of. There are about 500 members of CBFC, who preview around 13,500 films a year. The current chair is a famous dancer, Leela Samson, who controversially commented that almost 90% of her fellow board members were “uneducated political workers who did not understand their responsibility,” for which she later had to apologise. The current, and past, CEO of the board have been serving bureaucrats, on loan for this role. The final and biggest questions of the censor board faces, is how and why films are given the certifications they are.

In a very telling essay after his stint on the CBFC, journalist Mayank Shekhar wrote about the kinds of arguments that would take place at the meetings he attended: “Over the years, the focus of the Censor Board appears to have shifted from sex and violence to people’s “hurt sentiments” – some of it possibly real, but much of it imagined.”

The truth is that there are three broad problems in the certification of Indian films. First, the film board censors movies based on their moral outrage to sex or violence (as exhibited by the new CEO’s reaction), fear of minority groups getting upset (as witnessed by Shekhar), and the attempt to keep films with controversial subjects like the politics of Kashmir away from the mainstream audience, often by giving them A certification (as experienced by filmmaker Ashvin Kumar and reported by Index).

The second is the approach of filmmakers. Some, in order to get their films on TV by getting a U certificate, are only too happy to oblige any cuts the board might suggest, betraying any artist integrity. The other extreme is filmmakers who put in scenes with the intention of crossing swords with the board, thereby garnering some press attention for the movie. Shekhar writes in his essay of producer who was very disappointed that the board was not cutting any of his violent scenes, pleading: “Come on, how will people know this film exists? I’ve made a very violent film. How will I publicise it?”

The third is the allegation that board members take bribes in exchange for lenient certifications, as reported by Mint. Some feel the board goes easy on big production houses. This is because there are great financial implications involved with the certification process. Filmmakers want to make their investments back, both from the box office and lucrative satellite rights should their films be picked up for prime time viewing on television channels — as they can be with a U rating. Five Indian filmmakers have expressed their frustration with the lack of transparency in the decision making process of the CBFC, as well as perceived political interference. “I got an SMS from a senior member of a national political party, who told me that he was now with the Censor Board so to let him know if I needed any help,” revealed filmmaker Tigmanshu Dhulia.

However, ultimately, the entire argument boils down to the moral order, real or contrived, that Indian films must subscribe to should they want to be seen by the general public — both in movie halls and at a reasonable hour on television. In 1994, the censor board asked the makers of the movie Khuddar to replace the word “sexy” in a song with the word “baby”. So lyrics went like this (translated) – “baby, baby, baby, is what people call me.” In a repeat performance of a kind, in 2009, the world “sexy” was yet again replaced, but this time with “crazy” for the television version of the film. Over the years, kissing and even some sex scenes have slipped into Hindi cinema, as has a lot of cussing and plenty of violence. Nudity is only permitted in certain movies, which is either pixelated or viewed by a long-shot. Freedom of expression certainly seems in line behind the perceived notions of vulgarity of a few.

Thankfully, satire is alive and well in India, and enough websites are taking the CBFC and its new CEO to task. Others, like filmmaker Hansal Mehta, are determined to file an RTI – Right to Information – application to question every decision the board takes. As he says: “It only takes Rs 10 (under 1GBP) to file an RTI application. We live in a democracy, no one can stop me.”

This article was published on 29 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Politicians such as Rajya Sabha MP and BJP leader Subramanian Swamy feel justified in delaying the release of the film to “protect the culture of India”. Twitter users raved that Love, Simon would have been a landmark film that would humanize the LBGT+ community in India. However, at the tail end of International Pride Month, the film has still yet to be released. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Politicians such as Rajya Sabha MP and BJP leader Subramanian Swamy feel justified in delaying the release of the film to “protect the culture of India”. Twitter users raved that Love, Simon would have been a landmark film that would humanize the LBGT+ community in India. However, at the tail end of International Pride Month, the film has still yet to be released. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]