Chris Ames: Who’s behind the Chilcot Inquiry delay?

Despite his repeated assertions that it is nothing to do with him, it is now clear that British Prime Minister David Cameron not only has the power to hold back the long-awaited Chilcot Inquiry into the UK’s involvement in the Iraq war until after the election – but may actually do so. The prime minister who championed free speech but wants to duck out of TV election debates seems prepared to suppress the report of the Iraq inquiry on an equally flimsy pretext. If he does he will again find himself on the wrong side of the argument, perhaps with only opposition leader Ed Miliband for company.

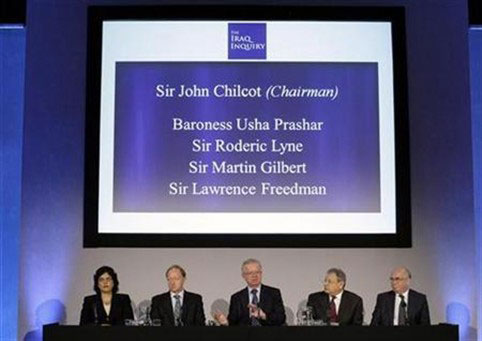

The inquiry has been in the headlines a lot lately, with politicians calling for the report to be published before the election and speculative stories about whether this is or isn’t possible. Having significantly compromised to extricate itself from a long-running dispute over which documents it can disclose in support of its findings, the inquiry, launched in 2009, is now undertaking the “Maxwellisation” process of notifying people that it intends to criticise and inviting their responses.

But publication before the election in May will depend not only on when Sir John Chilcot delivers the report to Cameron but what cut-off date is applied. Two weeks ago Cabinet Office minister Lord Wallace re-iterated that the government will hold back the report if it is not completed by the end of February. This is a month before parliament is dissolved on 30 March and pre-election “purdah” officially begins. Wallace justified this early deadline on the grounds that:

part of the previous Government’s commitment was that there would be time allowed for substantial consultation on and debate of this enormous report when it is published.

There was, in fact, no promise of “substantial consultation” from the previous government. It appears to have been invented to lengthen the process and justify interfering with an inquiry whose independence Cameron has repeatedly emphasized. Last month he said: “I am not in control of when this report is published. It is an independent report, it is very important in our system that these sort of reports are not controlled or timed by the government.”

A day after Wallace’s statement, Cameron repeated the error at Prime Minister’s Questions: “…it is up to Sir John Chilcot when he publishes his report. He will make the decision, not me.

A further day later Number 10 issued a “clarification”. According to the Telegraph, the prime minister’s deputy official spokesman said that in fact Cameron would have the final say on the timing the publication once has received the report. She said: “The point the Prime Minister has made is the timing of the report and its completion is a matter for the inquiry. “In terms of publication, the government would seek to publish it as swiftly as possible while ensuring parliament had the right time and opportunity to debate and look at it.”

This looks very much as if Cameron is prepared to suppress the report on the same grounds as Wallace gave – that MPs need a lot of time to study it. But Downing Street clearly knows that if Cameron expressly signed up to the February deadline he would completely contradict his own promise not to control the timing of the report. When I asked one of Cameron’s spokespeople whether he agrees with the deadline, he returned to the pre-clarification position of denial: “as the PM has said in the House of Commons, it is up to the Inquiry, not him”.

Meanwhile Labour leader Ed Miliband has kept very quiet on the issue and, having spoken to Labour’s media people, it is clear that they don’t want to talk about it either.But neither leader can fudge the issue much longer as a cross-party coalition of MPs, including Plaid Cymru, pushes for publication and challenges the government’s deadline. They have now secured a half day parliamentary debate on 29 January. The Lib Dems have challenged the government to publish the report within a week of receiving it, even during the election campaign. Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon called for politicians to unite on the issue, prompting Scottish Labour’s leader Jim Murphy to demand “the earliest possible publication”. Whether that is a rejection of the February deadline is unclear.

Looking further ahead, it seems unlikely that Cameron would really have the nerve to sit on the report, for as long as two months before the election. Even if you accept the official position that it needs to be put before parliament and cannot therefore be published during the election campaign, could he realistically refuse to publish it while parliament is sitting? With MPs treading water during March, to claim that there is not time to debate it would be entirely untenable.

We should never expect too much from an establishment inquiry, particularly without the key evidence. But the government’s argument for stalling the report is effectively that the desire of the political class for the perfect time and space to discuss it trumps voters’ right to be informed. After the massive loss in public trust that the Iraq war caused, surely Cameron wouldn’t dare.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

This article was posted on January 19, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org.