25 Jan 2023 | Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Belarus, Belgium, Botswana, Burma, China, Cuba, Czech Republic, Denmark, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Index Index, Ireland, Laos, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Netherlands, News and features, Nicaragua, North Korea, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Switzerland, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, United States, Yemen

A major new global ranking index tracking the state of free expression published today (Wednesday, 25 January) by Index on Censorship sees the UK ranked as only “partially open” in every key area measured.

In the overall rankings, the UK fell below countries including Australia, Israel, Costa Rica, Chile, Jamaica and Japan. European neighbours such as Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Denmark also all rank higher than the UK.

The Index Index, developed by Index on Censorship and experts in machine learning and journalism at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), uses innovative machine learning techniques to map the free expression landscape across the globe, giving a country-by-country view of the state of free expression across academic, digital and media/press freedoms.

Key findings include:

-

The countries with the highest ranking (“open”) on the overall Index are clustered around western Europe and Australasia – Australia, Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland.

-

The UK and USA join countries such as Botswana, Czechia, Greece, Moldova, Panama, Romania, South Africa and Tunisia ranked as “partially open”.

-

The poorest performing countries across all metrics, ranked as “closed”, are Bahrain, Belarus, Burma/Myanmar, China, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Laos, Nicaragua, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

-

Countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates performed poorly in the Index Index but are embedded in key international mechanisms including G20 and the UN Security Council.

Ruth Anderson, Index on Censorship CEO, said:

“The launch of the new Index Index is a landmark moment in how we track freedom of expression in key areas across the world. Index on Censorship and the team at Liverpool John Moores University have developed a rankings system that provides a unique insight into the freedom of expression landscape in every country for which data is available.

“The findings of the pilot project are illuminating, surprising and concerning in equal measure. The United Kingdom ranking may well raise some eyebrows, though is not entirely unexpected. Index on Censorship’s recent work on issues as diverse as Chinese Communist Party influence in the art world through to the chilling effect of the UK Government’s Online Safety Bill all point to backward steps for a country that has long viewed itself as a bastion of freedom of expression.

“On a global scale, the Index Index shines a light once again on those countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates with considerable influence on international bodies and mechanisms – but with barely any protections for freedom of expression across the digital, academic and media spheres.”

Nik Williams, Index on Censorship policy and campaigns officer, said:

“With global threats to free expression growing, developing an accurate country-by-country view of threats to academic, digital and media freedom is the first necessary step towards identifying what needs to change. With gaps in current data sets, it is hoped that future ‘Index Index’ rankings will have further country-level data that can be verified and shared with partners and policy-makers.

“As the ‘Index Index’ grows and develops beyond this pilot year, it will not only map threats to free expression but also where we need to focus our efforts to ensure that academics, artists, writers, journalists, campaigners and civil society do not suffer in silence.”

Steve Harrison, LJMU senior lecturer in journalism, said:

“Journalists need credible and authoritative sources of information to counter the glut of dis-information and downright untruths which we’re being bombarded with these days. The Index Index is one such source, and LJMU is proud to have played our part in developing it.

“We hope it becomes a useful tool for journalists investigating censorship, as well as a learning resource for students. Journalism has been defined as providing information someone, somewhere wants suppressed – the Index Index goes some way to living up to that definition.”

4 Jan 2016 | Estonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

In late November 2014, Estonia’s parliament made a historic decision to launch a Russian-language TV-channel as part of ERR, Estonia’s public broadcaster. A year later the channel is a reality: ETV+, ERR’s third channel debuted on 28 September.

The launch passed quite quietly, compared to the reaction that greeted the decision to create the channel. There were discussions about what the opening of a Russian-language channel in Estonia would mean. Would it be a tool of government propaganda or a knitting together of Estonia’s two communities, Estonian and Russian speakers into one community? From Russia there were clear expectations of a counter-weight to Russian media, which is widely followed by Estonia’s Russian speakers.

Speaking at a media conference hosted by ERR in June 2015, the ETV+ chief editor Darja Saar — a Russian project manager with no media experience — described the goals of the new channel: “We gave up the classical media rules from the very beginning, when we decided that we are not going to tell people what is right or wrong. Instead, we will follow people’s wishes – they are tired of just words and want deeds.”

The new TV channel aims not only to be an informer, educator and entertainer in the mould of a classical public service broadcasting channel but a leader in society and a hands-on problem solver.

In its two months on air, though, ETV+ has operated mostly as a traditional TV-channel offering morning programmes, debates, films and news. As required by law, all programmes are subtitled in Estonian. While geared toward Estonia’s Russian speakers, the station’s audience is mostly ethnic Estonians. In its debut week, ETV+ attracted 294,000 viewers. Ethnic Estonians accounted for 217,000 of the total and the other 77,000 were other ethnicities. On an average day during its first week 97,000 watched ETV+. On 28 September, its first day, 120,000 tuned in to sample the new station’s offerings.

ERR board member Ainar Ruussaar pointed out that ETV+ is a long-term project to improve Estonian society and was not about ratings. Yet the failure to draw a larger share of the Russian-speaking audience in the country may put that mission in jeopardy.

ERR has a fraught history with Russian-language programming. Promotion of Estonian language and culture has always been one of its core values. This served it well while it was under the Soviet system. Later, it countered Russian propaganda. But while times changed, ERR did not sufficiently move away from its core. In the early 2000s, the broadcaster, then under budgetary pressures, cut its slate of offerings in Russian. For years after its sole Russian-language production was a little-watched news programme.

In 2007, there was a serious discussion about launching a new Russian-language station after the 27 April violence sparked by the removal of the Bronze Soldier, a World War II memorial in Tallinn’s city centre. Then the political decision in favour of the Russian-language channel in Estonian Television was only one step away and there was readiness in the Russian-speaking audience to watch it. But as the riots faded, funding to get the project off the ground faltered and the opportunity to tie Russian speakers into ERR was missed. The country’s then prime minister Andrus Ansip said it was too difficult to compete with Russian TV channels so ERR’s Russian-language offerings would be limited to radio.

ETV+ is dancing on the razor’s edge. If it covers politics too much it will raise the ire of politicians who could cut its funding. Too much pro-government propaganda could turn off the Russian-speaking audience. Lurking in the background are ratings challenges that could force it to air infotainment and entertainment programmes.

As ETV+ turns two months old, it remains to be seen how it will develop. But connecting with Estonia’s Russian-speaking citizens must be its first goal.

This article was originally posted at indexoncensorship.org

This article was updated on 5/1/16 to clarify ETV+’s viewership numbers.

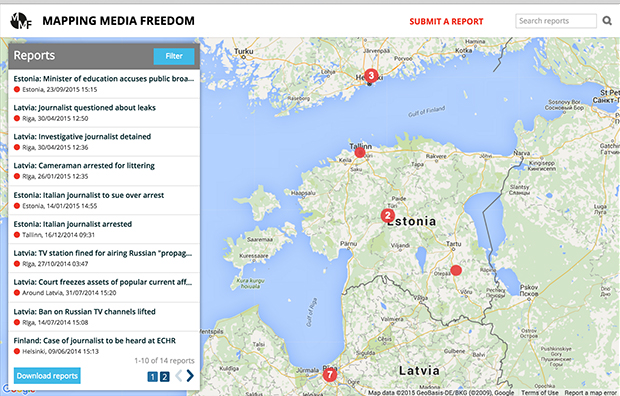

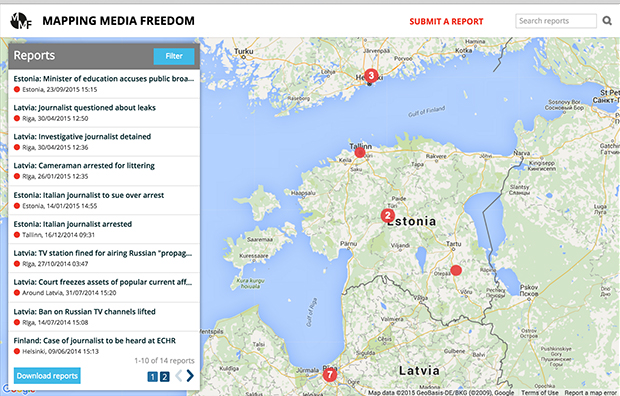

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

2 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features

On 19 September, the Estonian Minister of Education, Jürgen Ligi, accused the Estonian Public Broadcaster’s new Russian-language TV channel of disclosing secret government data.

The news report that sparked Ligi’s accusation dealt with the government’s proposal to teach high school students in Estonian. This move has been seen as ignoring the rights of the Russian-speaking minorities in the country.

Ligi implied that the report caused difficulties for the government. He also announced that, as the information was most likely leaked, there would be an official investigation. The head of the news department at the public broadcaster ETV, Urmet Kook, has already explained that the information was not received through a leak but was discovered during a routine check of public documents on different ministries.

This is the latest in a series of actions by the government against the media for disclosing data. Politicians see themselves as having a monopoly on truth and consider the press as nothing more than troublesome meddlers.

There are no specific laws relating to the media in Estonia, so all commercial outlets — apart from broadcast channels — are governed like any other business. The diverse legal landscape is subject to many different interpretations and there are no defined meanings of terms like ‘public interest’ and ‘public figure’, which makes it difficult for journalists to operate.

A typical example of the excessive limitations on the media is the Act on Defence of Personal Data. On first glance, it appears to be a noble attempt to defend sensitive information about the private lives of individuals, such as political affiliations, race and heritage. However, a closer look shows that it effectively prevents many journalists from uncovering information in the public interest. For example, a hospital denied a journalist access to information relating to a lump sum payment made in compensation for malpractice. In another case, a press officer at the Office of Public Prosecutor refused to acknowledge a criminal investigation into a well-known businessman. On both occasions, the reason for refusing to disclose the data was its sensitive nature.

Some caution is understandable. Any ethical person understands the necessity of the right to privacy. But over zealous and arbitrary enforcement makes it very difficult for journalists to warn the public of corruption, crime and dangerous individuals. With the protection offered by the act, released convicts can demand media outlets remove a story relating to their crimes, trials and sentences. Offenders can effectively hide in plain sight.

While these legal hurdles are a fact of life for many journalists, freelancers face extra obstacles. Larger media companies are given preferential treatment by the government, as are journalists who present information in the desired way. Estonian media channels also tend not to work with freelancers on a one-time basis. Such practices hurt freelance journalists, especially younger writers who lack established sources and connections. Without proper access to information, they are deprived of a proper livelihood.

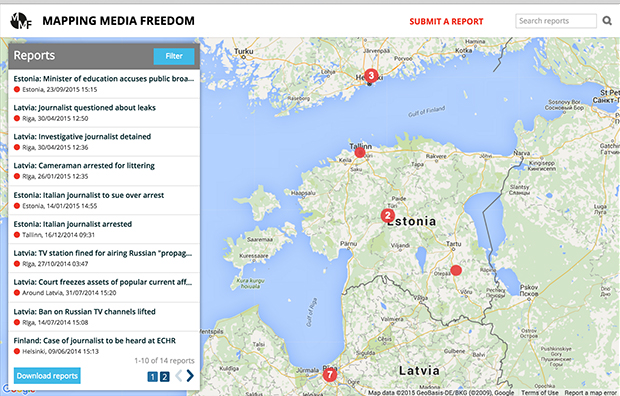

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

10 Oct 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features

An alarming judgment has been issued by the European Court of Human Rights that could seriously affect online comment threads.

The judgment in the case Delfi AS v Estonia suggests that online portals are fully responsible for comments posted under stories, in apparent contradiction of the principle that portals are “mere conduits” for comment and cannot be held liable.

Further, the unanimous ruling suggests that if a commercial site allows anonymous comments, it is both “practical” and “reasonable” to hold the site responsible for content of the comments.

The ruling concerns a case against Estonian site Delfi.ee. In 2006, Delfi ran a story about a ferry operator’s changing of routes. This story lead to some heated debate in the comments thread, with, according to the judgment “highly offensive or threatening posts about the ferry operator and its owner”.

The owner sued in Estonia, and in 2008, a court found Delfi responsible for defamation. Delfi appealed on the grounds the the European eCommerce Directive suggested it should be regarded as a “passive and neutral” host. The case eventually ended up in Strasbourg.

Today’s ruling contains several alarming lines for anyone who runs a website with comments. For example, the court suggests that:

Given the nature of the article, the company should have expected offensive posts, and exercised an extra degree of caution so as to avoid being held liable for damage to an individual’s reputation.”

This is curious: any moderator will tell you that controversial comments can appear in the unlikeliest of places.

The judgment goes on:

The article’s webpage did state that the authors of comments would be liable for their content, and that threatening or insulting comments were not allowed. The webpage also automatically deleted posts that contained a series of vulgar words, and users could tell administrators about offensive comments by clicking a single button, which would then lead to the posts being removed. However, the warnings failed to prevent a large number of insulting comments from being made, and they were not removed in good time by the automatic-word filtering or by the notice-and-take-down notification system.”

This seems to suggest that Delfi’s attempts to make to filter vulgar content and remind commenters of their liability have actually been used against them. Even the reporting system is not enough for the court.

Perhaps most worryingly, the judgment delivers another severe blow to online anonymity:

However, the identity of the authors would have been extremely difficult to establish, as readers were allowed to make comments without registering their names. Therefore many of the posts were anonymous. Making Delfi legally responsible for the comments was therefore practical; but it was also reasonable, because the news portal received commercial benefit from comments being made.”

It is difficult to see how any site would allow anonymous comments if this ruling stands as precedent.

This would appear to be truly troubling judgment for website operators and moderators.

The ruling is not yet final and may be subject to further review.

This article was originally posted on 10 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org