20 Feb 2015 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

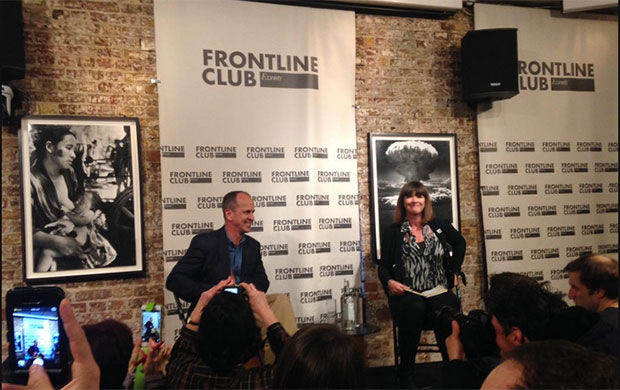

Peter Greste spoke to a Frontline Club audience about his arrest and detention in Egypt. (Photo: Milana Knezevic / Index on Censorship)

Peter Greste, the Al Jazeera journalist recently released after 400 days in Egyptian jail, met a packed room at London’s Frontline Club on Thursday, where he spoke about his time in jail, the campaign for his release and fellow journalists still imprisoned in Egypt. “An attack on journalism, an attack on freedom of speech, is an attack on the wider society,” he said.

“I remember that day well,” he said, recounting 29 December 2013, when a group of around eight men came to his Cairo hotel room and without explanation started searching it, before talking him away. While he was aware that the media was under some pressure in Egypt, the arrest came as a surprise. He felt as long as they stuck to their journalistic principles and didn’t push boundaries, they would be fine.

“There have been plenty of stories before where I’ve pushed boundaries, when I fully expected to get a knock on the door from the police, when I know I’ve upset governments,” he explained. But this time around, he hadn’t gone looking for difficult stories or made a conscious effort to try and challenge the government, so he “genuinely didn’t think it was going to be an issue.”

Greste was imprisoned together with Al Jazeera producer Baher Mohamed and Al Jazeera English’s Cairo bureau chief Mohamed Fahmy. He said they forced themselves to consider that they might be convicted, but never seriously believed it.

While there were “some very dark moments”, he insisted anger wasn’t his dominant emotion, believing that letting anger take hold of the situation would only hurt himself. They were broadly treated with respect in prison, and never physically threatened. “The problem is that in prison…what really matters is your own head, your own mind and how you cope with it.”

Egypt

Index has reported extensively on the situation confronting free expression in the country

Committee to Protect Journalists named Egypt as one of the world’s top 10 jailers of journalists in Dec 2014

Reporters Without Borders: World Press Freedom Index ranks the country as 159

Freedom House: Classifies Egypt as “not free”

Greste spoke of the importance of having a routine and some structure to his day, crediting seemingly simple things like meditation, exercise, studying and even cooking with helping him though the ordeal.

“The only way through is to set your horizon, to set a target date, to set something that’s manageable,” he said. “What you do is narrow your horizon, to the thing that you think you can cope with. Sometimes that was the end of next week, or it would be to the next visit. Sometimes it would be simply to the end of the day.”

Today, he doesn’t feel traumatised, and believes that we are all more capable of dealing with difficult situations than we think. And when discussing the conditions in prison, it was clear he had kept his humour. “The less said about the toilets the better,” he joked.

If his detention had been a surprise, so was his release. He had been expecting his brother for a visit, when he got the unexpected message to pack his bags — he was going home. Himself, Fahmy and Mohamed had discussed the possibility that one of them might be released before the others, and all agreed that if that were to happen, there would be no doubt that that person should go.

And yet, Greste said walking away and leaving Mohamed and others (Fahmy was receiving medical treatment at the time) behind was not easy. “And I still feel that and I still feel quite anguished about it.” His two colleagues have now been released on bail, with their retrial set to start on Monday.

Greste was also keen to remind us that while the three of them had been given the most media attention, many others had been caught up in the case — including three young students, a businessman and journalists sentenced in absentia.

“We can’t forget that sympathy tends to go with people who you identify with. As a European, as a white guy, it’s easier for white Europeans to identify with me than it is to identify with an Egyptian. I’m not suggesting for a second that that makes Baher’s case any less worthy. And in a way we need to bear that in mind, that because of that trend, it’s so easy to let local journalists slip through the cracks,” he also added. “It is the locals that get hit, and the freelancers in particular.”

He said he’ll continue to report, though he is not yet sure what form his work will take. He also hopes to continue to speak out for press freedom.

“One of the most extraordinary elements of this, and one that we are in danger of losing, if we do not make a conscious effort to hold on to, is the unity of purpose that emerged within the media community around our case. For some reason, the community right across the globe pulled together in a way that I think is absolutely unprecedented; we’ve never seen anything like this ever before,” he said.

“If we lose that sense of purpose, then we lose something that we have created of enormous value. I think its very difficult to maintain, particularly under the current circumstances, but I think it’s incumbent on everybody to recognise it, to make use of it, not just in our case but in the case of every journalist that’s been imprisoned.”

This article was posted on 20 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

18 Jul 2014 | Mapping Media Freedom, Netherlands, News and features

Rena Netjes

Dutch journalist Rena Netjes was sentenced in absentia to ten years in prison in Egypt. The Egyptian government’s case against her and other journalists generated media interest from around the world. With the help of her colleagues at the Dutch Union for Journalists she’s now raising the issue of human rights and press freedom violations in Egypt in The Netherlands and abroad.

When freelance correspondent Netjes arrived at Schiphol airport on the 4th of February this year, she had just slipped out of Egypt after finding out she was blacklisted by the Egyptian government and would have to stand trial for on charges of working for Al Jazeera, terrorism and endangering national security. At home in The Netherlands, she recounted her escape with the help of Dutch diplomats in Egypt to newspapers and television in what seemed like a media circus.

While Netjes managed to flee Egypt, her colleagues were not so fortunate. Three Al Jazeera journalists, the Canadian-Egyptian Mohamed Fahmy, Egyptian Baher Mohamed and the Australian Peter Greste, have been sentenced to seven years, after being held in an Egyptian prison since December 2013.

In June, from the safety of her living room in The Netherlands, she learned that she has been sentenced to ten years in prison. She was convicted on the charges of spreading false information and promoting the banned Muslim Brotherhood. She was accused of working for Al Jazeera, which the Egyptian government claims promotes the views of the Muslim Brotherhood. Netjes says she only had coffee with the chief editor on one occasion. British journalists Sue Turton and Dominic Kane have also been sentenced in absentia to ten years imprisonment.

For Netjes, who lived and worked in Egypt for many years, the verdict means she might never be able to set foot in the country again.

“It’s still an emotional roller coaster,” she told Index on Censorship. She’s relieved to be free but is concerned about her colleagues now. “It’s hard to imagine these guys are in prison, in the hands of sadists.”

Her career as a foreign correspondent in Egypt is over, for now at least. Netjes would run the risk of being arrested if she returned. She can’t even go to most countries in the Middle East because of extradition agreements. “Even Lebanon extradites ‘terrorists’ to Egypt”, she said.

With the spotlight on her in The Netherlands, Netjes said she sees an opportunity to generate attention for Egypt’s human rights violations, the lack of press freedom and specifically the plight of the other journalists, who weren’t able to escape prison sentences. “They now depend on international pressure, by politicians and diplomats behind the scenes, but also on awareness raised by colleagues around the world”.

Netjes speaks frequently to Dutch and international media and is invited to panel discussions and public human rights events. “I’m trying to turn this traumatic experience into something positive,” she said. “I have a more platform to explain what is going on Egypt, to raise the subject of the abuses in Egypt”.

The Dutch Union for Journalists (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Journalisten, NVJ) jumped in to support Netjes’ case and the campaign for free media in Egypt. On July 8, NVJ-President Marjan Enzlin paid a visit to the Egyptian embassy in The Netherlands to address the issue.

At the embassy Enzlin expressed her concern about the trial and her worries about the lack of freedom for media in Egypt. “We told him these verdicts are a strong violation of press freedom. We asked him to deliver this message to his president”, she told Index on Censorship. “He told us he is not in the position to intervene. And then he even lectured us on how western media is poorly informed and is deliberately spreading negative stories about Egypt. It was ridiculous”.

Enzlin acknowledges that without Netjes’ involvement, the case probably wouldn’t have generated so much attention in Dutch media and politics. “It is because of Rena that this case is so high on the Dutch agenda. But through Rena, we should now fight for the others. We as free journalists in a free country have to make noise about the case. We should be a thorn in one’s side”.

Being one of the highest ranked countries in terms of media freedom, Enzlin believes the Dutch media should stand up. “The resistance needs to come from here”, she said. “We are spoiled in The Netherlands. We see it as our duty to support and help our colleagues in countries like Egypt”.

Immediately after the verdict in Egypt, the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs Frans Timmermans summoned the Egyptian ambassador. The Dutch government insists the trial wasn’t fair, and urged Egypt to improve human rights. The NVJ wants to make sure this kind of diplomatic pressure won’t wane over time. “This requires long term commitment, we have to keep the pressure up”, Enzlin says.

The NVJ has several actions and protests lined up. They will publish a photo gallery on their website of all journalists who have been convicted in Egypt. They have sent a letter to the Egyptian ambassador in The Netherlands asking for assurances that Netjes can travel to the country for her appeal without fear of detention. If Netjes can’t go to Egypt safely, the NVJ requested to go in her place.

After the Dutch parliament’s summer recess, the NVJ will ask for another meeting with the Egyptian ambassador. They plan to invite MPs to join them to add more political pressure. The union will also organise a protest at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, in front of the gate for flights to Egypt. “We will make banners saying ‘journalists are not terrorists’. Something Egypt will not be happy with.”

Netjes is still publishing stories on issues in Egypt. “I still have my sources in Egypt feeding me with information because they see that I am in the position to speak and write freely”. Meanwhile, spreading the word about the deplorable situation for journalists and activists in Egypt became a mission on its own.

“I am deprived of my freedom to travel, but that is nothing compared to what the guys who are imprisoned are going through”, she said. “I will not rest before they are free.”

This article was updated on July 21, 2014 to reflect that Marjan Enzlin is the President of NVJ, not Director as previously stated.

More reports from The Netherlands via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Journalist denied entrance to public court hearing

‘Rules for using drones by journalists too restricted’

Journalists’ cameras seized by police

Dutch magazine on trial for photographing princess

This article was posted on July 18, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

14 Jul 2014 | Draw the Line, Young Writers / Artists Programme, Youth Board

Three Al Jazeera journalists were among those sentenced to prison on terrorism charges.

In 1997, British journalist Robert Fisk interviewed Bin Laden. Fisk was not accused of being a terrorist, he was only doing his job. For decades, journalists have been interviewing terrorists, criminals and drug lords, because this is their job; to give a voice to everybody, whether they agree with them or not.

Last month, Egypt sentenced three Al Jazeera journalists to seven years in prison under the country’s anti-terrorism laws; they were accused of spreading false information, as well as supporting the now banned Muslim Brotherhood. In an extremely polarised political climate, giving a voice to the Muslim Brotherhood was deemed inciteful and inflammatory.

Art has been a means of stretching the boundaries, but can art sometimes be a public safety risk?

A series of cartoons, some of which depicted Prophet Mohammed, published by a Danish newspaper in 2005 sparked angry and violent protests across the Arab world. The same happened again when a 13 minute trailer of a movie called Innocence of Muslims appeared on Youtube two years ago. Earlier this year, French comic and political activist Dieudonné M’bala M’bala was banned from performing after his shows were found to incite racial hatred and anti-semitic sentiment by French courts. The comedian was also banned from entering the United Kingdom.

These cases raise a very important question: When does giving a platform to extremist views through art or journalism become an act of terrorism? Should artists or journalists be exempt from terrorism laws or should inflammatory works be banned?

Get involved the discussion using the hashtag #IndexDrawtheLine and tell us — where do you draw the line?

27 Jun 2014 | Egypt, News and features, Young Writers / Artists Programme

On Monday, three Al Jazeera journalists were sentenced in Egypt to 7 years imprisonment each, to the shock of media outlets and NGOs worldwide. Cartoonist Ben Jennings shares his take on journalism in the country.

Index strongly condemns the jailing of journalists for doing their job.

In light of the sentences, Michelle Betz writes about her own experience of being on trial in Egypt as part of an NGO, Shahira Amin looks at the blow to press freedom in Egypt the trial has had, while Casey Prottas attended the minute’s silence outside BBC Broadcasting House, held exactly 24 hours after the verdict was read.