2 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features

On 19 September, the Estonian Minister of Education, Jürgen Ligi, accused the Estonian Public Broadcaster’s new Russian-language TV channel of disclosing secret government data.

The news report that sparked Ligi’s accusation dealt with the government’s proposal to teach high school students in Estonian. This move has been seen as ignoring the rights of the Russian-speaking minorities in the country.

Ligi implied that the report caused difficulties for the government. He also announced that, as the information was most likely leaked, there would be an official investigation. The head of the news department at the public broadcaster ETV, Urmet Kook, has already explained that the information was not received through a leak but was discovered during a routine check of public documents on different ministries.

This is the latest in a series of actions by the government against the media for disclosing data. Politicians see themselves as having a monopoly on truth and consider the press as nothing more than troublesome meddlers.

There are no specific laws relating to the media in Estonia, so all commercial outlets — apart from broadcast channels — are governed like any other business. The diverse legal landscape is subject to many different interpretations and there are no defined meanings of terms like ‘public interest’ and ‘public figure’, which makes it difficult for journalists to operate.

A typical example of the excessive limitations on the media is the Act on Defence of Personal Data. On first glance, it appears to be a noble attempt to defend sensitive information about the private lives of individuals, such as political affiliations, race and heritage. However, a closer look shows that it effectively prevents many journalists from uncovering information in the public interest. For example, a hospital denied a journalist access to information relating to a lump sum payment made in compensation for malpractice. In another case, a press officer at the Office of Public Prosecutor refused to acknowledge a criminal investigation into a well-known businessman. On both occasions, the reason for refusing to disclose the data was its sensitive nature.

Some caution is understandable. Any ethical person understands the necessity of the right to privacy. But over zealous and arbitrary enforcement makes it very difficult for journalists to warn the public of corruption, crime and dangerous individuals. With the protection offered by the act, released convicts can demand media outlets remove a story relating to their crimes, trials and sentences. Offenders can effectively hide in plain sight.

While these legal hurdles are a fact of life for many journalists, freelancers face extra obstacles. Larger media companies are given preferential treatment by the government, as are journalists who present information in the desired way. Estonian media channels also tend not to work with freelancers on a one-time basis. Such practices hurt freelance journalists, especially younger writers who lack established sources and connections. Without proper access to information, they are deprived of a proper livelihood.

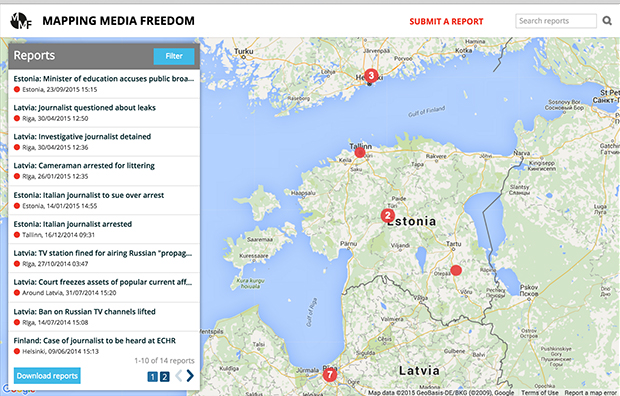

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

23 Sep 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Address for response c/o

Campaign for Freedom of Information

Unit 109

Davina House

137-149 Goswell Rd

London EC1V 7ET

The Rt Hon David Cameron MP

Prime Minister

10 Downing Street

London SW1A 2AA

21 September 2015

Dear Prime Minister,

We are writing to express our serious concern about the government’s approach to the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act and in particular about the

Commission on Freedom of Information and the proposal to introduce fees for tribunal appeals under the Act.

It is clear from the Commission’s terms of reference that its purpose is to consider new restrictions to the Act. The Commission’s brief is to review the Act to consider: whether there is an appropriate balance between openness and the need to protect sensitive information; whether the ‘safe space’ for policy development and implementation is adequately recognised and whether changes are needed to reduce the Act’s ‘burden’ on public authorities. The ministerial announcement of the Commission’s formation stressed the need to protect the government’s ‘private space’ for policy-making.1 There is no indication that the Commission is expected to consider how the right of access might need to be improved.

The Commission’s five members consist of two former home secretaries, Jack Straw and Lord Howard of Lympne (Michael Howard), a former permanent secretary, Lord Burns, a former independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, Lord Carlile of Berriew (Alex Carlile) and the chair of a regulatory body subject to FOI, Dame Patricia Hodgson. A government perspective on the Act’s operation will be well represented on the Commission itself.

One of the Commission’s members, Jack Straw, has repeatedly maintained that the Act provides too great a level of disclosure. Mr Straw has argued that the FOI exemption for the formulation of government policy should not be subject to the Act’s public interest test.2 Such information would then automatically be withheld in all circumstances even where no harm from disclosure was likely or the public interest clearly justified openness. Mr Straw has also suggested that the Supreme Court exceeded its powers in ruling that the ministerial veto cannot be used to overturn a court or tribunal decision under the Act unless strict conditions are satisfied.3 He has argued that there should be charges for FOI requests and that it should be significantly easier for public authorities to refuse requests on cost grounds.4 Mr

Straw’s publicly expressed views cover all the main issues within the Commission’s terms of reference. Speaking in the Commons shortly before the Commission’s appointment, the Justice Secretary, Michael Gove, expressly cited Mr Straw’s views with approval saying that he had been ‘very clear

about the defects in the way in which the Act has operated’.5

Another member of the Commission is Ofcom’s chair, Dame Patricia Hodgson. In 2012, when she was its deputy Chair, Ofcom stated that ‘there is no

doubt’ that the FOI Act has had a ‘chilling effect’ on the recording of information by public authorities. One of the Commission’s priorities is likely to be to consider whether there has been such an effect — and whether the right of access should be restricted to prevent it. Ofcom has also

called for it to be made easier for authorities to refuse requests on cost grounds and for the time limits for responding to requests to be increased.6

An independent Commission is expected to reach its views based on the evidence presented to it rather than the pre-existing views of its members. Indeed, in appointing members to such a body we would expect the government to expressly avoid those who appear to have already reached and expressed firm views. It has done the opposite. The government does not appear to intend the Commission to carry out an independent and open minded

inquiry. Such a review cannot provide a proper basis for significant changes to the FOI Act. The short timescale for the Commission’s report, which is due by the end of November, further reinforces this impression. At the time of writing, half way towards the Commission’s final deadline, it has so far not even invited evidence from the public.

The FOI Act was the subject of comprehensive post-legislative scrutiny by the Justice Committee in 2012 which found that the Act had been ‘a significant enhancement of our democracy’ and concluded ‘We do not believe there has been any general harmful effect at all on the ability to conduct business in the public service, and in our view the additional burdens are outweighed by the benefits’. We question the need for a further review now.

We are also concerned about the government’s proposal to introduce fees for appeals against the Information Commissioner’s decisions.7 Under the proposals, an appeal to the First-tier Tribunal on the papers would cost £100 while an oral hearing would cost £600. The introduction of fees for employment tribunal appeals has led to a drastic decrease in the number of cases brought. A similar effect on the number of

FOI appeals is likely. Requesters often seek information about matters of public concern, so deterring them from appealing will deny the public information of wider public interest. On the other hand, fees are unlikely to discourage public authorities from challenging pro-disclosure decisions, so the move will lead to an inequality of arms between requesters and authorities. Given that the Ministry of Justice and the Justice Committee have recently begun to review the impact of employment tribunal fees on access to justice we find it remarkable that this proposal should be put forward before the results of their inquiries are even known.

We regard the FOI Act as a vital mechanism of accountability which has transformed the public’s rights to information and substantially improved the scrutiny of public authorities. We would deplore any attempt to weaken it.

Yours sincerely,

Act Now Training, Ibrahim Hasan, Director

Action on Smoking and Health, Deborah Arnott, Chief Executive

Against Violence and Abuse, Donna Covey, Director

Animal Aid, Andrew Tyler, Director

Archant, Jeff Henry, Chief Executive

ARTICLE 19, Thomas Hughes, Executive Director

Article 39, Carolyne Willow, Director

Belfast Telegraph, Gail Walker, Editor

Big Brother Watch, Emma Carr, Director

British Deaf Association, Dr Terry Riley, Chair

British Humanist Association, Andrew Copson, Chief Executive

British Muslims for Secular Democracy, Nasreen Rehman, Chair

BSkyB, John Ryley, Head of Sky News

Burma Campaign UK, Mark Farmaner, Director

Campaign Against Arms Trade, Ann Feltham, Parliamentary Co-ordinator

Campaign for Better Transport, Stephen Joseph, Chief Executive

Campaign for Freedom of Information, Maurice Frankel, Director

Campaign for National Parks, Ruth Bradshaw, Policy and Research Manager

Campaign for Press & Broadcasting Freedom, Ann Field, Chair

Centre for Public Scrutiny, Jacqui McKinlay, Executive Director

Chartered Institute of Library & Information Professionals, Nick Poole, Chief Executive

Children England, Kathy Evans, Chief Executive

Children’s Rights, Alliance for England, Louise King, Co-Director

CN Group Limited, Robin Burgess, Chief Executive

Community Reinvest, Dr Jo Ram, Co-Founder

Computer Weekly, Bryan Glick, Editor in Chief

CORE, Marilyn Croser, Director

Corporate Watch / Corruption Watch, Susan Hawley, Policy Director

Coventry Telegraph, Keith Perry, Editor

Cruelty Free International, Michelle Thew, Chief Executive Officer

CTC, the national cycling charity, Roger Geffen, Campaigns and Policy Director

Daily Mail, Paul Dacre, Editor; Jon Steafel, Deputy Editor; Peter Wright, Editor Emeritus; Charles Garside, Assistant Editor; Liz Harley, Head of Legal

Debt Resistance UK

Deighton Pierce Glynn, Sue Willman, Partner

Democratic Audit, Sean Kippin, Managing Editor

Disabled People Against Cuts, Linda Burnip, Co-Founder

Down’s Syndrome Association, Carol Boys, Chief Executive

Drone Wars UK, Chris Cole, Director

English PEN, Jo Glanville, Director; Maureen Freely, President

Equality and Diversity Forum, Ali Harris, Chief Executive

Evening Standard, Sarah Sands, Editor

Exaro, Mark Watts, Editor in Chief

Finance Uncovered, Nick Mathiason, Director

Friends of the Earth, Guy Shrubsole, Campaigner

Friends, Families and Travellers, Chris Whitwell, Director

Gender Identity Research and Education Society, Christl Hughes, Legal Consultant

Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, Peter Newell, Co-ordinator

Global Witness, Simon Taylor, Co-Founder and Director

Greenpeace, John Sauven, Executive Director

Guardian News and Media Limited, Gillian Phillips, Director of Editorial Legal Services

Hacked Off, Dr Evan Harris, Executive Director

i, Oliver Duff, Editor

Inclusion London, Tracey Lazard, Chief Executive Officer

independent.co.uk, Christian Broughton, Editor

Index on Censorship, Jodie Ginsberg, Chief Executive Officer

INQUEST, Deborah Coles, Co-Director

Involve, Simon Burall, Director

Johnston Press Editorial Board, Jeremy Clifford, Chairman

Jubilee Debt Campaign, Sarah‐Jayne Clifton, Director

KM Group, Geraldine Allinson, Chairman

Labour Campaign for Human Rights, Andrew Noakes, Director

Law Centres Network, Julie Bishop, Director

Leigh Day, Russell Levy, Head of Clinical Negligence

Liberty, Bella Sankey, Policy Director

Liverpool Echo, Alastair Machray, Editor

London Mining Network, Richard Solly, Co-ordinator

Loughborough and Shepshed Echo, Andy Rush, Editor

LUSH, Mark Constantine, Managing Director

medConfidential, Phil Booth, Co-ordinator

Metro, Ted Young, Editor

Migrants’ Rights Network, Don Flynn, Director

Move Your Money UK, Fionn Travers-Smith, Campaign Manager

mySociety, Mark Cridge, Chief Executive

NAT (National AIDS Trust), Deborah Gold, Chief Executive

National Commission on Forced Marriage, Nasreen Rehman, Vice Chair

National Union of Journalists, Michelle Stanistreet, General Secretary

Newbury Weekly News, Andy Murrill, Group Editor

News Media Association, Santha Rasaiah, Legal, Policy and Regulatory Affairs Director

Newsquest, Toby Granville, Editorial Development Director; Peter John, Group Editor for Worcester/Stourbridge

Nursing Standard, Graham Scott, Editor

NWN Media, Barrie Phillips-Jones, Editorial Director

Odysseus Trust, Lord Lester of Herne Hill QC, Director

Open Data Manchester, Julian Tait, Co-Founder

Open Knowledge, Jonathan Gray, Director of Policy and Research

Open Rights Group, Jim Killock, Executive Director

OpenCorporates, Chris Taggart, Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer

Oxford Mail and The Oxford Times, Simon O’Neill, Group Editor

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals Foundation, Dr Julia Baines, Science Policy Advisor

Press Association, Pete Clifton, Editor in Chief; Jonathan Grun, Emeritus Editor

Press Gazette, Dominic Ponsford, Editor

Prisoners’ Advice Service, Lubia Begum-Rob, Joint Managing Solicitor

Privacy International, Gus Hosein, Executive Director

Private Eye, Ian Hislop, Editor

Public Concern at Work, Cathy James, Chief Executive

Public Interest Research Centre, Richard Hawkins, Director

Public Law Project, Jo Hickman, Director

Pulse, Nigel Praities, Editor

Race on the Agenda, Andy Gregg, Chief Executive

Renewable Energy Foundation, Dr John Constable, Director

Reprieve, Clare Algar, Executive Director

Republic, Graham Smith, Chief Executive Officer

Request Initiative CIC, Brendan Montague, Founder and Director

Rights Watch (UK), Yasmine Ahmed, Director

RoadPeace, Beccie D’Cunha, Chief Executive Officer

Salmon and Trout Conservation (UK), Guy Linley-Adams, Solicitor

Sheila McKechnie Foundation, Linda Butcher, Chief Executive

Society of Editors, Bob Satchwell, Executive Director

South Northants Action Group, Andrew Bodman, Secretary

South Wales Argus, Kevin Ward, Editor

Southern Daily Echo, Ian Murray, Editor in Chief

Southport Visitor, Andrew Brown, Editor

Spinwatch, David Miller, Director

Stop HS2, Joe Rukin, Campaign Manager

Sunday Life, Martin Breen, Editor

TaxPayers’ Alliance, Jonathan Isaby, Chief Executive

Telegraph Media Group, Chris Evans, Editor and Director of Content

The Corner House, Nick Hildyard, Founder and Director

The Independent, Amol Rajan, Editor

The Independent on Sunday, Lisa Markwell, Editor

The Irish News, Noel Doran, Editor

The Mail on Sunday, Geordie Greig, Editor

The Sun, Tony Gallagher, Editor; Stig Abell, Managing Editor

The Sunday Post, Donald Martin, Editor

The Sunday Times, Martin Ivens, Editor

The Times, John Witherow, Editor

Transform Justice, Penelope Gibbs, Director

Transparency International UK, Robert Barrington, Executive Director

Trinity Mirror, Simon Fox, Chief Executive; Lloyd Embley, Group Editor in Chief; Neil Benson, Editorial Director Regionals Division

Trust for London, Bharat Mehta, Chief Executive

UNISON, Dave Prentis, General Secretary

Unite the Union, Len McCluskey, General Secretary

Unlock Democracy, Alexandra Runswick, Director

War on Want, Vicki Hird, Director of Policy and Campaigns

We Own It, Cat Hobbs, Director

Welfare Weekly, Stephen Preece, Editor

WhatDoTheyKnow, Volunteer Administration Team

Women’s Resource Centre, Vivienne Hayes, Chief Executive Officer

WWF-UK, Debbie Tripley, Senior Legal Adviser

Zacchaeus 2000 Trust, Joanna Kennedy, Chief Executive

38 Degrees, Blanche Jones, Campaign Director

4in10 Campaign, Ade Sofola, Strategic Manager

1 www.gov.uk/government/speeches/freedom-of-information-new-commission

2 The Rt Hon Jack Straw MP, oral evidence before Justice Committee, Post-Legislative Scrutiny of the Freedom of Information Act, 17 April 2012, Q.344. www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmjust/96/120417.htm

3 BBC Radio 4, Today programme, 14 May 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/may/14/court-exceeded-its-power-in-ordering-publication-of-charles-memos-straw. The Supreme Court’s ruling related to the use of the veto to block the release of Prince Charles’ correspondence with ministers in response to a request by the Guardian newspaper

4 Oral evidence to Justice Committee, 17 April 2012, Q.355 & Q.363. www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmjust/96/120417.htm

5 House of Commons, oral questions, 23.6.15, col. 754, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm150623/debtext/150623‐0001.htm#15062354000032

6 Ofcom, February 2012, Written evidence to the Justice Committee, Post-legislative Scrutiny of the Freedom of Information Act, Volume 3, Ev w176-177. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmjust/96/96vw77.htm

7 The Government response to consultationon enhanced fees for divorce proceedings, possession claims, and general applications in civil proceedings and Consultation on further fees proposals

7 Jul 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, mobile, News and features

Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, of ruling party Fidesz (Pic © European People’s Party/CreativeCommons/Flickr)

The Hungarian parliament has voted yes to plans to allow the government and other public authorities to charge a fee for the “human labour costs” of freedom of information (FOI) requests this week, as well as granting sweeping new powers to withhold information. It just needs the signature of President Janos Ader before it becomes law.

The bill, submitted by Minister of Justice László Trócsányi, was published on the government website just days before the vote, on 3 July, precluding any meaningful debate about the proposal. It is widely believed that through this initiative, governing party Fidesz is trying to put a lid on a number of scandals involving wasteful government spending, uncovered through FOI requests.

According to Transparency International, the bill “appears to be a misguided response by the Hungarian government to civil society’s earlier successful use of freedom of information tools to publicly expose government malpractice and questionable public spending”.

One provision of the bill allows public bodies to refuse to make certain data public for 10 years if deemed to have been used in decision-making processes, according to Index award-winning Hungarian investigative news platform Atlatszo.hu. As virtually any piece of information can be used to build public policies upon, this gives the government a powerful argument not to answer FOI requests.

The bill also allows government actors to charge fees for fulfilling FOI request. Until now, government actors could ask for the copying expenses of documents. From now on, they can ask the person filing the request to cover the “human labor costs” of the inquiry.

It is not yet clear how much members of the public will have to pay. “There will be a separate government decree in the future regarding the costs that can be charged for a FOI request,” Tibor Sepsi, a lawyer working for Atlatszo.hu, says.

Because the public has no means to verify whether these costs are well-grounded, and at some government agencies the salaries are known to be very high, the government might be in a discretionary position to ask prohibitive costs for answering the FOI requests, critics of the amendment say.

“The FOI requests usually ask for data that are already available somewhere in electronic format, therefore no government body can say that fulfilling a request involves gathering information,” says Tamás Bodoky, the editor-in-chief of Atlatszo.hu.

“It is unacceptable to plead for extraordinary workload and expenses when much of the requests refer to things that should be published in accordance with transparent pocket rules. This information should be readily available in the settlement of accounts and reports,” he adds.

The work of investigative journalists and watchdog NGOs is further complicated through another provision, regarding copyright. In some cases, the government will be able to refer to copyright issues and only give limited access to certain documents, without making them publicly available.

While the bill will make life harder for those making FOI requests, Sepsi also points out that the situation is not as bad as it may initially seem: “The government will have half a dozen of new ways to reject vexatious FOI requests, but on the implementation level, ordinary courts, the constitutional court or the Hungarian National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information Authority will have the power to keep things under reasonable control.”

Nevertheless, Hungarian and international NGOs working for the transparency of public spending and government decisions are protesting against the bill. An open letter, signed by the groups Atlatszo.hu, K-Monitor, Energiaklub Szakpolitikai Intézet and Transparency International Magyarország Alapítvány has been sent to the Minister of Justice Trócsányi, to the Hungarian National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information Authority, as well as the MPs whose votes decided the fate of the proposal.

“We believe the government would do the right thing if – instead of rolling back on transparency – it would increase the so-called proactive disclosure, meaning that it would publish the information regarding its functioning in electronic format, without a request. We can provide international examples where this can be achieved simply, without extraordinary costs. This would increase not only the transparency of public spending, but the number of FOI requests would also decrease significantly,” the letter argues.

After the vote, a group of 50 opposition MPs pledged to ask the constitutional court to review the text.

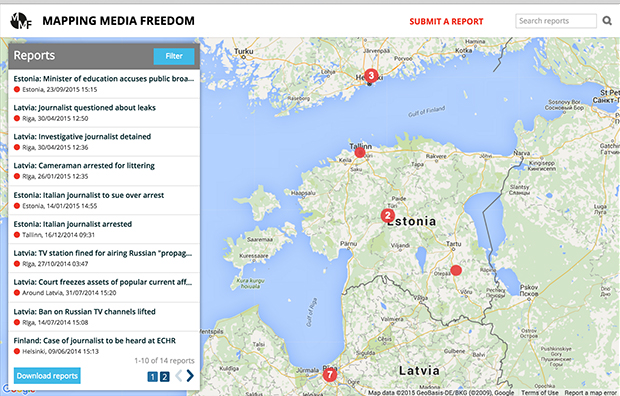

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

This article was posted on 6 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

14 May 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

It has been hailed as the damp squib to end damp squibs. The let down of let downs. The mother, the pearl of non-stories. Prince Charles’s “black spider” letters to various government ministers including the prime minister Tony Blair over eight months between 2004 and 2005 have elicited barely an OMG! or a WTF?, but many, many, mehs.

“Where’s the crazy stuff about homeopathy?”, we mumble. “Isn’t there supposed to be some stuff about talking to vegetables, or converting to Kaballah? Aliens? Surely some crop circles?”

Nothing. Or at least nothing worth shaking a divining rod at. One mention of herbal medicines. A hat tip to the Patagonian toothfish and the “poor old albatross”. Lots and lots of impressive detail about agricultural policy.

If anything, having scanned the letters I found myself thinking more highly of Prince Charles than previously. He clearly knows his stuff (or at least has had the good sense to employ someone who knows their stuff) and is genuinely concerned for the farming and fishing sectors.

That is not to say I am comfortable with the existence of these letters. I am a dyed-in-the-wool, though realistic, republican. That is to say, I sincerely disagree with monarchy in any form, but realise there’s not much point in going on about it in the UK. Most people seem reasonably happy with the archaic, arcane set up of the British monarchy. They’re not doing much harm, really, and doesn’t the Duchess of Cambridge have lovely hair? And none of it really matters.

Except that it does matter. The weirdness of the entire set up was exposed after the birth of Princess Charlotte in April. Royal correspondents openly spoke of her assumed lifelong role as second fiddle to her brother, George, who will one day be king.

The BBC did that thing where it reminds you that it is a state broadcaster, informing subjects about how the newborn had brought joy to the entire nation. I am not yet sufficiently misanthropic to be displeased by the birth of a child, but the whole thing had the feeling of the celebration of a successfully completed pagan ritual.

I sometimes wonder if it’s different if you were raised with this stuff: if the British are immune to the oddness of it all.

Times journalist Hugo Rifkind, a writer I admire and generally believe to be right about pretty much everything, confused me with a column after the Supreme Court’s decision that the letters should be published in which he suggested that those who wanted the letters published were guilty of taking the prince too seriously: “[The letters are] the late-night rages of Mr Angry of Highgrove,” Rifkind wrote. “They’re the green ink letters to the press. In a sane and sensible nation, they wouldn’t matter at all.”

The problem is that this isn’t a sane and sensible nation. It is a nation where, purely by birth, Charles has a constitutional role to play. In a republic, the adult first-born of a president could sent whatever letters they wanted, and we’d leave them to it. In a monarchy, you cannot just be the child of a head of state: if that role depends on lineage, then it follows that Charles, while not head of state himself, still has power. It is one thing for a head of state to have regular meetings with her prime minister, but another for her son to throw his weight around on specific policy issues, even if it is all relatively boring stuff. If the monarchy is essentially meaningless and impotent, then scrap it. If not, well, it scrapping is even more urgent.

The government must also take its share of the blame for the fiasco that led to a 10-year legal fight with The Guardian at an estimated cost of £400,000. Why such determination to block the publication of a few letters on farming? Why the panic?

One supposes that they worried not just about the monarchy (former Attorney General Dominic Grieve suggested that the release of the letters would hamper Charles’s future ability to govern), but also about the implications: freedom of information gone wild. If a newspaper can demand to see correspondence from the heir to the throne, where does it all end?

Tony Blair claimed that one of his biggest regrets in government was the introduction of the Freedom of Information Act, which he claimed hampered candid conversations at cabinet level. I have some sympathy with this viewpoint, but I think the benefit of FOI has outweighed any negatives.

But now, with the publication of these old letters, ministers fear they will lose control of the freedom of information process. Hence attempts to strengthen a blanket ministerial veto on freedom of information requests. This on top of the exemption to FOI for senior royals introduced in 2011, in response to the black spider case. It’s a regressive step in an age where we keep being told of the need for open government. But that’s the mess monarchy has got us in to.

We’re not even a week into the new government, and already alarm bells are ringing over freedom of speech (with the government’s extremism plans) and freedom of information. The next few months and years will see bitter wrangling between government and civil libertarians.

If only we knew someone who would be sure that his concerned letters to ministers would be given full attention.

This column was posted on 14 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org