Fighting to speak freely: balancing privacy and free expression in the information age

Good morning.

First I would like to thank the Internet Librarian International conference for inviting me to speak to you this morning. It is an honour to speak to a group of people who have been so important in forming me as a person. As a child I was the kind of person who got six books out of the library on a Saturday afternoon and had read all of them by Monday morning. I was addicted to reading, hooked on the spellbinding power and beauty of words.

Today I am very proud to work for an organisation that defends expression in all its forms; one that recognises not only the power of words, but also of images, of music, of performance – to convey ideas, thoughts, opinions and feelings.

In this morning’s talk I want to talk about how we balance what often seems like competing rights: the rights to privacy, security – the right to life – and freedom of expression in an information age. I want to argue that these should not be seen as mutually exclusive rights but importantly symbiotic rights, which must co-exist equally for the other to survive. I will illustrate this from examples from our work at Index on Censorship, and consider some of the challenges and causes for optimism for the next few years.

First, a little about Index on Censorship. Index on Censorship is a 43 year old organisation founded by the poet Stephen Spender in response to what seemed like a simple request: what could the artists and intellectuals of the West do to support their counterparts behind the Iron Curtain and those under the thumb of oppressive regimes elsewhere? Organisations like Amnesty and PEN already existed, doing then – as now – a formidable job of petitioning and campaigning, particularly on the cases of the imprisoned. What more could be done? The answer – those who established Index decided – was to publish the works of these censored writers and artists and stories about them. Index on Censorship magazine was born and we have continued to produce the magazine – this magazine – on at least a quarterly basis ever since. The motivation, as Stephen Spender wrote in the first edition of the magazine, was to act always with concern for those not free, responding to the appeals from Soviet writers to their Western counterparts. “The Russian writers,” Spender wrote, “seem to take it for granted that in spite of the ideological conditioning of the society in which they live, there is nevertheless an international community of scientists, writers and scholars thinking about the same problems and applying to them the same human values. These intellectuals regard certain guarantees of freedom as essential if they are to develop their ideas fruitfully… Freedom, for them, consists primarily of conditions which make exchange of ideas and truthfully recorded experiences possible.”

I will come back later to that notion of ‘conditions which make exchange of ideas possible’ as a central tenet of my argument regarding the essential interplay between privacy and free expression.

I hope you will allow me a brief pause before that, however, to describe to you the evolution of Index. Over time, Index has developed a campaigning and advocacy arm in addition to its publishing work, but we remain focused on the notion that it is that by providing a voice to the voiceless – by providing the information that others seek to keep from us – that we take the first important steps to overcoming censorship.

Why is it important to tackle censorship? Sometimes we forget to ask ourselves this question because we take it for granted that freedom is a good thing. Consider all those who were quick to shout ‘Je Suis Charlie’ following the attacks on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo – the knee jerk reaction in Western liberal democracies is often to say you are for free speech, without ever really stopping to consider why you might be for it. Or why free speech is and of itself a good thing.

I would argue this failure to understand the value of free speech lies at the heart of one of the dilemmas we face in modern democracies where free speech is being gradually eroded – where ‘Je Suis Charlie’ quickly became ‘Je Suis Charlie, but…’.

It is vital to understand the value inherent in free expression to understand why some of the current tensions between privacy and security on the one hand and free speech on the other exist. It is also crucial for understanding ways to tackle the dangerous trade offs that are increasingly being made in which free expression is seen as a right that can legitimately be traded off against privacy and security.

So forgive me for what might seem like making a small diversion to rehearse some of the arguments on the value of free expression. Locke, Milton, Voltaire have all written eloquently on the benefits of free expression, but I think Mill expresses it best when he talks of free expression being fundamental to the “permanent interests of man as a progressive being.” “The particular evil of silencing the expression of an opinion,” he argues in On Liberty, “is that it is robbing the human race… If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth; if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth produced by its collision with error.”

This latter argument is particularly powerful when we consider, for example, the introduction of Holocaust denial laws. Such laws suggest that there are some truths so precious that they have to be protected by laws, rather than having their truth reinforced by repeated “collision with error.” You can imagine authoritarian regimes everywhere looking at such laws and rubbing their hands with glees at the prospect of being able to impose a single view of history on the populace, without any kind of challenge.

The free exchange of ideas, opinions, and information is in Mill’s – and others’ – doctrine a kind of positive cacophony from which clear sounds emerge. In this doctrine, it is not just the having of ideas, but the expressing of them that becomes vital. And it is here that those who would pit freedom of expression against privacy find grounds for the undermining of the latter. If the goal of free expression is the exchange of ideas for the better progression of mankind through the discovery of truths, then keeping ideas secret undermines that goal.

This is the particularly pervasive argument used in Western liberal democracies to justify surveillance. If you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear, the mantra goes: in liberal democracies, we’re not interested in your ideas, we’re just out to get the bad guys committing crimes. It shouldn’t stop you expressing yourself.

Except that it does. Anyone who has read Dave Eggers book The Circle will be familiar with a world in which privacy is demolished, in which every action and movement is recorded – in an inversion of Mill’s vision – for the betterment of society. The result is a world in which actions and habits are changed because there is no longer a private sphere in which thought and behaviour can developed. And it is a world that is not just a dystopian alternative reality. A study by the PEN American center earlier this year demonstrated that knowledge of mass surveillance by governments is already changing the way in which writers work. The report, Global Chilling, showed an astonishing one third of writers – 34 percent – living in countries deemed “free” – based on the level of political rights and civil liberties – have avoided writing or speaking on a particular topic, or have seriously considered it, due to fear of government surveillance. Some 42 percent of writers in “free countries” have curtailed or avoided activities on social media, or seriously considered it, due to fear of government surveillance, the survey found.

In countries that are not free, the consequence of a lack of privacy is acute. Colleagues in Azerbaijan, for example, note that authorities are quick to demonstrate the country’s openness by arguing a lack of curbs on social media.

As one commentator points out, such curbs are unnecessary, because as soon as an individual expresses an opinion unpalatable to government on an outlet such as Twitter, they are soon targeted, arrested, and jailed – often on spurious charges unrelated to free speech but which effectively at curbing it.

We are now also seeing, increasingly, the tactics pursued by illiberal regimes being adopted by supposedly liberal ones. Consider the use for example of UK anti-terror laws to snoop on the phone calls of the political editor of The Sun newspaper. British police used the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act – legislation introduced explicitly to tackle terrorism – to obtain the phone records of Tom Newton Dunn for an investigation into whether one of its officers had leaked information about a political scandal, thereby seriously comprising the basic tenet of a free and independent media: the confidentiality of sources.

And such methods, indeed even the hardware, are being used elsewhere to quash free expression. As the journalist Iona Craig wrote for Index on Censorship magazine last year: “Governments going after journalists is nothing new. But what is increasingly apparent is that those listening and watching when we work in countries infamous for their consistent stifling of freedom of speech and obstruction of a free press, are often doing so with the infrastructure, equipment or direct support of supposedly “liberal” Western nations.

Craig, a regular reporter from Yemen, describes the phone tapping and other surveillance methods that put her and her sources at risk and how she and her colleagues are resorting to traditional methods of reporting – meeting contacts in person, using pen and paper, to evade surveillance.

Privacy, then, is vital for communication, for the free exchange of ideas and information. Index knows this from a long history that has ridden both the analogue and the digital wave. In our latest edition of the magazine, for example, retired primary school teacher Nancy Martinez Villareal recalls smuggling pieces of information to the Revolutionary Left Movement in Chile in documents hidden in lipstick tubes. Copies of our own magazine were smuggled into eastern Europe during the 1980s, by intrepid reporters hiding the copies under bunches of then much-coveted bananas. We ourselves now communicate with persecuted individuals in some of the world’s most repressive environments for free speech using encrypted communications such as PGP. Again in the latest edition of the magazine, Jamie Bartlett, director of the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media at the Demos think tank, writes about new auto-encryption email services such as Mailpile and Dark Mail that will allow private communication to evade the censors. In addition to these services, projects like Ethereum and Maidsafe are building an entirely new web out of the spare power and hard drive space of millions of computers put on the network by their owners. Because the network is distributed across all these individual computers, it is more or less impossible to censor.

Surveillance is just one example in which we see the argument of security being used to justify incursions into an array of civil liberties from privacy to free expression.

In fact, privacy campaigners have been at the forefront of campaigning against mass surveillance and other techniques.

And while I hope I have shown that privacy and free expression are both necessary so that the other can flourish, it would be remiss of me not to caution against any temptation to let privacy rights – which often appear all the more important in both an age of mass surveillance and a bare-all social media culture – trump freedom of expression in such a way that they prevent us, as per the Mill’s doctrine, coming closer to the truth.

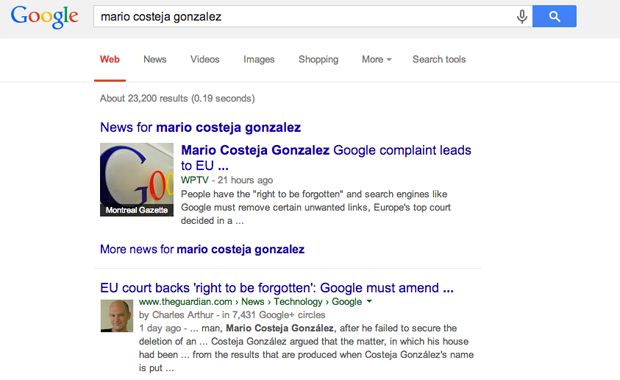

It is for this reason that Index on Censorship opposed the so-called ‘Right to be Forgotten’ ruling made in Europe last year. Europe’s highest court ruled in May 2014 that ‘private’ individuals would now be able to ask search engines to remove links to information they considered irrelevant or outmoded. In theory, this sounds appealing. Which one of us would not want to massage the way in which we are represented to the outside world? Certainly, anyone who has had malicious smears spread about them in false articles, or embarrassing pictures posted of their teenage exploits, or even criminals whose convictions are spent and have the legal right to rehabilitation. In practice, though, the ruling is far too blunt, far too broad brush, and gives far too much power to the search engines.

The ruling came about after a Spanish man, Mario Costeja González requested the removal of a link to a digitised 1998 article in La Vanguardia newspaper about an auction for his foreclosed home, for a debt that he had subsequently paid. Though the article was true and accurate, Costeja Gonzalez argued that the fact this article was commonly returned in name searches gave an inaccurate picture of him. After hearing the case, the European Court of Justice ruled that search engines must remove links to any content that is “inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant”. The content itself is not deleted, but Google will not list it in search results.

Index warned at the time that the woolly wording of the ruling – its failure to include clear checks and balances, or any form of proper oversight – presented a major risk. Private companies like Google should not be the final arbiters of what should and should not be available for people to find on the internet. It’s like the government devolving power to librarians to decide what books people can read (based on requests from the public) and then locking those books away. There’s no appeal mechanism, very little transparency about how search engines arrive at decisions about what to remove or not, and very little clarity on what classifies as ‘relevant’. Privacy campaigners argue that the ruling offers a public interest protection element (politicians and celebrities should not be able to request the right to be forgotten, for example), but it is over simplistic to argue that simply by excluding serving politicians and current stars from the request process that the public’s interest will be protected.

We were not the only ones to express concern. In July last year the UK House of Lords’s EU Committee published a report claiming that the EU’s Right to be Forgotten is “unworkable and wrong”, and that it is based on out-dated principles.

“We do not believe that individuals should have a right to have links to accurate and lawfully available information about them removed, simply because they do not like what is said,” it said.

Here are some examples of stories from the UK’s Telegraph newspaper to which links have been removed since the ruling:

• A story about a British former convent girl who was jailed in France for running a ring of 600 call girls throughout Europe in 2003. Police were tipped-off about her operation by a former colleague following an argument.

• An article from 2008 about a former pupil from a leading boarding school who returned to his halls of residence after a night out drinking and drove his car around the grounds at speeds of 30mph before crashing. The Telegraph goes on to add: “He eventually collided with a set of steps in a scene reminiscent of the 1969 cult classic movie starring Michael Caine. His parents had given him the silver Mini just the day before.”

• A story which includes a section taken from the rambling “war plan” of Norwegian man Anders Behring Breivik to massacre 100 people.

• A story from 2009 on The Telegraph’s property page documenting how a couple and their two sons gave up pressured London life and moved into a rolling Devon valley.

Search engines removed such articles at the request of indviduals. Publishers have no real form of appeal against the decision, nor are the organisations told why the decision was made or who requested the removals. Though the majority of cases might be what privacy campaigners deem legitimate – such as smear campaigns – the ruling remains deeply problematic. We believe the ruling needs to be tightened up with proper checks and balances – clear guidelines on what can and should be removed (not leaving it to Google and others to define their own standards of ‘relevance’), demands for transparency from search engines on who and how they make decisions, and an appeals process. Without this, we could find that links to content that is true, factual, legitimately obtained – and indeed vitally relevant for the searcher, even if not deemed to be so by the individual – could be whitewashed from history.

In this way we see that protection of the individual, using notions of harm defined by the individual themselves – is used as an argument for censorship. I want to use the remainder of my talk to discuss ways in which this drive to shield from potential and perceived harm, is having an impact.

Let us start with libraries and the example of the United States’ Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA), which brought new levels of Internet censorship to libraries across the country. CIPA was signed into law in 2000 and found constitutional by the Supreme Court in 2003: two previous attempts at legislating in this area – the Communications Decency Act and the Child Online Protection Act, were held to be unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court on First Amendment grounds.

As the Electronic Frontier Foundation has written eloquently on this, the law is supposed to encourage public libraries and schools to filter child pornography and obscene or “harmful to minors” images from the library’s Internet connection. However, as with all such laws, the devil is in the implementation not the original intention.

Schools and libraries subject to CIPA must certify that the institution has adopted an internet safety policy that includes use of a “technology protection measure”— in other words filtering or blocking software — to keep adults from accessing images online that are obscene or child pornography. The filtering software must also block minors’ access to images that are “harmful to minors,” in other words, sexually explicit images that adults have a legal right to access but would be inappropriate for young people.

Only images, not text or entire websites, are legally required to be blocked. Libraries are not required to filter content simply because it is sexual in nature. Libraries aren’t required to block social networking sites, political sites, sites advocating for LGBT issues, or sites that explore controversial issues like euthanasia.

However, this is what happens – either through technological illiteracy or overzealous implementation.

As all of you will be aware, filters don’t work effectively. Not only can filters block perfectly legitimate content, they can also fail to block certain content that is obscene.

We saw this in the case of Homesafe, a network-level filter that was being offered by one of Britain’s largest internet providers. The filter was designed to block adult content on the network level, but in late 2011 IT expert Cherith Hateley demonstrated that the filter failed to block Pornhub, which offers thousands of free explicit videos and is ranked as the third largest pornography provider on the web. Hateley found that on the Pornhub website the HomeSafe blocking page had been relegated to a small box normally reserved for advertising, leaving its adult content fully accessible.

In addition to the challenge of poor filtering, there is the problem of transparency. We don’t know exactly what’s being blocked. There’s no documentation of which libraries are filtering what specific websites and most filtering technology companies keep their algorithms for blocking sites a closely guarded secret. Without clarity on precisely what is being blocked, by whom, and how often, it’s impossible to know what content is being filtered and therefore whether libraries are being over censorious.

Where does this leave ethics? Librarians play an important role in ensuring free speech online. The American Library Association’s code of ethics states: “We uphold the principles of intellectual freedom and resist all efforts to censor library resources.”

This impulse to protect from harm is also seeping away from internet controls and filters into the broader public discourse and nowhere is this more alarming than in universities. I want to argue that the impulse I described earlier – of a private realm that is so crucial for the development of ideas and in some cases their incubation and dissemination – is being warped by an extension of the idea of personal physical safety into a demand for a kind of safety from ideas that is shutting down debate more widely.

It is clear that something is going wrong at universities. Institutions that should be crucibles for new thinking, at the forefront of challenges to established thought and practice, are instead actively shutting down debate, and shying away from intellectual confrontation.

Driven by the notion that students should not be exposed to ideas they find – or might find – offensive or troubling, student groups and authorities are increasingly squeezing out free speech – by banning controversial speakers, denying individuals or groups platforms to speak, and eliminating the possibility of “accidental” exposure to new ideas through devices such as trigger warnings.

The trend was particularly noticeable last year when a number of invited speakers withdrew from university engagements – or had their invitations rescinded – following protests from students and faculty members. Former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice withdrew from a planned address at Rutgers University in New Jersey after opposition from those who cited her involvement in the Iraq war and the Bush administration’s torture of terrorism suspects; Brandeis University in Massachusetts cancelled plans to award an honorary degree to Islam critic Ayaan Hirsi Ali; and Christine Lagarde backed out of a speech at Smith College following objections by students over the acts of the International Monetary Fund, which Lagarde runs. In the UK, the University of East London banned an Islamic preacher for his views on homosexuality. And a new law – a counter-terrorism bill – was proposed in Britain that could be used to force universities to ban speakers considered “extremist”.

Registering your objection to something or someone is one thing. Indeed, the ability to do that is fundamental to free expression. Actively seeking to prevent that person from speaking or being heard is quite another. It is a trend increasingly visible in social media – and its appearance within universities is deeply troubling.

It is seen not just in the way invited speakers are treated, but it stretches to the academic fraternity itself. Last year, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign withdrew a job offer to academic Steven Salaita following critical posts he made on Twitter about Israel.

In an open letter, Phyllis Wise, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign chancellor, wrote: “A pre-eminent university must always be a home for difficult discussions and for the teaching of diverse ideas… What we cannot and will not tolerate at the University of Illinois are personal and disrespectful words or actions that demean and abuse either viewpoints themselves or those who express them. We have a particular duty to our students to ensure that they live in a community of scholarship that challenges their assumptions about the world but that also respects their rights as individuals.”

These incidents matter because, as education lecturer Joanna Williams wrote in The Telegraph newspaper: “If academic freedom is to be in anyway meaningful it must be about far more than the liberty to be surrounded by an inoffensive and bland consensus. Suppressing rather than confronting controversial arguments prevents criticality and the advance of knowledge, surely the antithesis of what a university should be about?”

Yet, increasingly, universities seem to want to shut down controversy, sheltering behind the dangerous notion that protecting people from anything but the blandest and least contentious ideas is the means to keep them “safe”, rather than encouraging students to have a wide base of knowledge. In the US, some universities are considering advising students that they don’t have to read material they may find upsetting, and if they don’t their course mark would not suffer. The introduction of “trigger warnings” at a number of universities is a serious cause for concern.

In the UK, increasing intolerance for free expression is manifest in the “no platform” movement – which no longer targets speakers or groups that incite violence against others, but a whole host of individuals and organisations that other groups simply find distasteful, or in some way disqualified from speaking on other grounds.

The decision to cancel an abortion debate at Oxford in late 2014, which would have been held between two men – and noted free speech advocates – came after a slew of objections, including a statement from the students’ union that decried the organisers for having the temerity to invite people without uteruses to discuss the issue. More recently, a human rights campaigner was barred from speaking at Warwick University – a decision that was subsequently overturned – after organisers were told she was “highly inflammatory and could incite hatred” and a feminist was banned from speaking at the University of Manchester because her presence was deemed to violate the student union’s “safe space” policy.

Encountering views that make us feel uncomfortable, that challenge our worldview are fundamental to a free society. Universities are places where that encounter should be encouraged and celebrated. They should not be places where ideas are wrapped in cotton wool, where academic freedom comes to mean having a single kind of approved thinking, or where only certain “approved” individuals are allowed to speak on a given topic.

Index on Censorship knows well the importance of the scholar in freedom of expression. Though we have come to be known as Index, the charity itself is officially called Writers and Scholars Educational Trust, an effort to capture as simply as possible the individuals whom we intended to support from the outset. The title was never intended to be exclusive, but the inclusion of “scholar” signals the importance our founders attached to the role of the academic as a defender and promoter of free speech. In 2015, as we watch the spaces for free expression narrow, I hope that together we can work doubly hard to ensure that traditional bastions for free speech – such as universities and indeed libraries – remain arena for the clash of ideas, not the closure of minds.