15 Jun 2020 | China, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”113563″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]An extraordinary event in the history of not just Hong Kong but of the world took place exactly one year ago. A massive crowd, which according to some estimates was around two million strong, marched through the streets of the most cosmopolitan city on the China coast to call for the withdrawal of a proposed extradition bill that many felt would undermine the rule of law in Hong Kong. They also took action to express their anger at the brutality police had shown in dealing with a protest a few days before. And they demonstrated to show, more generally, that they were concerned that key features of local life that made the city different from its mainland neighbours, including greater freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, were under threat.

The marchers marched because they felt that the Chinese Communist Party leadership was failing to respect the second two words in the “One Country, Two System” framework that was supposed to structure relations between Beijing and Hong Kong for the first 50 years after the 1997 Handover that changed the latter from a British colony to a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. Xi Jinping and company were failing to respect the promise that Hong Kong would enjoy a “high degree of autonomy” until 2047. The marchers marched because they felt that Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam, chosen through an election in which fewer than 2,000 local residents were eligible to vote, was aiding and abetting this process. She was, in fact, the one who was championing the hated extradition bill, which would allow activists to be taken over the border to stand trial on the mainland if Beijing wished this to happen.

What made the march extraordinary in world historical terms? Even in an era that is witnessing wave after wave of protest struggles, the size of the crowd was unusual. There are few if any examples of roughly a quarter of the members of a sizeable political community taking to the streets at once. Yet, as Hong Kong is home to fewer than eight million people, that is what happened on 16 June 2019.

To mark that anniversary, we are publishing an excerpt from the closing pages of Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, a work written by historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom, with contributions by the journalist Amy Hawkins. Published earlier this year by Columbia Global Reports, it places that massive mid-June march and related 2019 events into historical and comparative perspective.

Vigil – whose lead author has recently contributed both a short story and two commentaries to Index and spoke last year at an Index event on a panel with the Guardian’s Tania Branigan that focused on the 30th anniversary of Tiananmen – makes particularly fitting reading right now. This is because in recent weeks Beijing and its local allies have made their most disturbing moves yet to destroy what little is left of the “autonomy” Hong Kong was promised. Showing disrespect for the Chinese national anthem has been criminalised, for example; highly respected figures in the democracy movement known for consistently advocating moderate tactics have been arrested; and Beijing has announced it will impose a sweeping new anti-sedition law on Hong Kong.

Resistance continues. Activists face greater risks than ever, however, as mass arrests and police brutality have become routine. In line with arguments in Vigil, the Hong Kong democracy movement increasingly resembles the against-long-odds efforts to combat autocratic rule waged in Poland after martial law was imposed there late in 1981 or the protracted anti-colonial struggle against powerful, recalcitrant empires that have been carried out in many parts of the world.

***

Water by Jeffrey Wasserstrom

Hong Kong has long been a place with varied and deep associations with water. “Harbor” is the second term in its two-character name, coming after a word most often translated as “fragrant”. Fish and seafood figure centrally in the storied local cuisine. Hong Kong first gained economic importance due to its role as a hub of trade involving vessels that moved goods across rivers and seas. Humid air, mist, and the torrents of water that lash the city during typhoons are key parts of the local climate. Umbrellas served as protest symbols in 2014. While the city teetered on the brink in 2019, activists striving to create a new alternative world in the streets and in malls and in airport arrival and departure halls in the midst of scenes of destruction, urged one another to “be water,” to adapt their tactics continually to changing circumstances. To resemble “water” means to be flexible in one’s actions, going one place but quickly heading to another if there is too much resistance. The idea can be traced back to longstanding Chinese philosophical traditions, especially Daoism (though metaphors linked to water are important in Confucian texts as well). It has a more specific referent, though, to perhaps the most famous Hong Konger, martial artist and movie star Bruce Lee. “Don’t get set into one form, adapt it and build your own, and let it grow. Be like water,” he said. “Now water can flow, or it can crash! Be water, my friend.”

There’s also the metaphor of the hundred-year flood, the (inaccurate) myth that rivers overflow their banks once a century. Just as the 2019 protest movement was underway in Hong Kong, the author Adam Hochschild published a powerful essay about the parallels of American politics in the years 1919 and 2019. Hochschild conjured up the image of a very particular sort of hundred-year flood: the unleashing of ugly nativist rhetoric in America during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, and now again during that of Donald Trump. Focusing as I have on the events treated in the preceding chapters on my mind, his essay set me wondering whether there were parallels and imperfect analogies linked to events of a century ago worth considering when trying to make sense of the current Hong Kong crisis. There are, I think—providing that we place the past of Shanghai, once the most cosmopolitan city on the China coast, beside Hong Kong’s present.

What exactly happened in that great port of the Yangzi Delta one hundred years ago? There was a dramatic series of protests in which young people took leading roles. There was a general strike. On the whole, the protesters behaved in peaceful ways, but there were some ugly incidents, during which they roughed up people they viewed as outsiders. One goal of the movement was to stop a widely disliked document from going into effect. The protesters directed much of their ire at government officials they viewed as immoral and too ready to do the bidding of men in a distant capital. They also called for the release of protesters who had been arrested and complained about police using too much force in dealing with demonstrators. The movement became in large part a fight for the right to speak out. The protests in the city were preceded by, built on, and expanded a repertoire of action developed during a series of earlier struggles, as some participants in the 1919 demonstrations had been part of shorter waves of activism in 1915 and 1918 and in some cases even in 1905. New tactics were added to the mix in 1919. So were new symbols: for example, a distinctive type of headwear became associated with the protests, as students eschewed wearing straw hats made in Japan for locally made cotton ones.

This analogy is far from perfect. The Shanghai protests of 1919 were part of a nationwide struggle, known as the May Fourth Movement, in honor of the day of the year’s first major demonstration, which took place in Beijing. The current crisis, by contrast, began and has stayed centered in Hong Kong, as did the 2014 Umbrella Movement before it. There have been many more arrests this year, and there were no paving stones thrown or fires set by activists in Shanghai a century ago. The document the protesters of 1919 disliked was not a local bill but an international accord: The Treaty of Versailles, the post–World War I agreement that they objected to because it passed control of former German possessions in Shandong Province to Japan rather than returning them to Chinese control. While one student died from the injuries he received at the hands of the police during the initial protest on May 4, 1919, many fewer demonstrators and bystanders were injured in any part of China one hundred years ago than have been injured in Hong Kong during 2019.

The protesters of 1919 even succeeded in gaining more concessions from the warlords in control of Beijing than those of 2019 have managed to secure. In the immediate wake of the Shanghai General Strike, which stands out as one of the most important of all May Fourth Movement collective actions, three officials that the students claimed were too cozy with Tokyo were removed from their positions and the protesters arrested in Beijing were released. The Chinese delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, who had a role in the proceedings as both China and Japan had come into World War I on the side of the Allies, refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles. These successes by the protesters help to explain why the May Fourth Movement has long been hailed in China as a triumphant struggle. By contrast, while Carrie Lam withdrew the extradition law in September, there have been no moves toward concession regarding the other key demands of the protesters. The authorities have not released those who have been arrested, appointed an independent commission to investigate allegations of police violence, nor retracted their description of early protests as “riots.” Lam has not resigned. There is no universal suffrage in Hong Kong.

But while the May Fourth Movement has a hallowed place in Chinese history now, it was for decades considered largely a failure. While the Chinese delegation to Paris refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles, the accord went into effect anyway. Former German territories in Shandong fell under Japanese control. The May Fourth activists were no more successful at preventing territory they cared about from going from the control of one colonial power to another. And the Japanese seizure of Shandong, which was preceded by its seizing of Korea and Taiwan, was followed in 1931 by Tokyo taking Manchuria and later moving further into China and other neighboring lands.

Japan asserted in many cases that it was not taking over territories, but freeing them from colonial rule, and allowing them to be governed at last by locals. They made this claim about Shanghai, proclaiming in the early 1940s that it was finally liberated from all forms of foreign control, even as Japanese troops and Chinese puppet officials control the city. They made this claim about Manchuria as they put Pu Yi, the ethnically Manchu former Last Emperor of the Qing Dynasty, on the throne, as a ruler beholden to Tokyo. They did not talk of a single empire with multiple systems, but rather of a Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. Beijing, too, does not talk of having an empire, but its handling of Tibet and Xinjiang rhymes with Tokyo’s imperial approach. Beijing’s dreams for Hong Kong, which are nightmares to those on the streets, rhyme with Tokyo’s proclamations about Shanghai. The terms are new— “One Country, Two Systems,” “Greater Bay Area”—but when it comes to fantasies and raw power, there are disturbing echoes.

History does not repeat itself. In 1919, the Western powers actively aided Japan’s move into Shandong. Viewed within a hundred-year framework, the limited international concern about Hong Kong’s fate is deeply worrying. So, too, are the signals some world leaders, including Vladimir Putin and Donald J. Trump, have been sending to Xi Jinping during the current crisis, which convey a sense that whatever he does will be just fine with them, as long as it does not impinge on their plans for their own nations. Hundred-year floods can wreak many different kinds of damage.

Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink was published in February 2020. To read more about the book click here[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

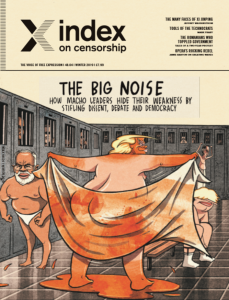

22 Jan 2020 | News, Volume 48.04 Winter 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In the winter 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley argues that a new generation of democratic leaders is actively eroding essential freedoms, including free speech” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Like brothers in arms, they revel in the same set of characteristics. They share them, and their favourite ways of using them, on social media.

Like brothers in arms, they revel in the same set of characteristics. They share them, and their favourite ways of using them, on social media.

From Orbán to Trump and from Bolsonaro to Johnson, national leaders who want to dismiss analysis with a personalised tweet, and never want to answer a direct question, have come to power – and are using power to silence us. They like to think of themselves as strongmen but what, in fact, they are doing is channelling the worst kind of machismo.

For toughness, read intolerance of disagreement. They are extremely uncomfortable with public criticism. They would rather hold a Facebook “press conference” where they are not pressed than one where reporters get to push them on details they would rather not address. Despite running countries, they try to pretend that those who hold them to account are the elite who the public should not trust.

While every generation has its “tough” leaders, what’s different about today’s is that they are everywhere, and learning, copying and sharing their measures with each other – aided, of course, by the internet, which is their ultimate best friend. And this is not just a phenomenon we are seeing on one continent. Right now these techniques are coming at us from all around the globe, as if one giant algorithm is showing them the way. And it’s not happening just in countries run by unelected dictators; democratically elected leaders are very firmly part of this boys’ club.

Here are some favoured techniques:

If you don’t like some media coverage, you look at ways of closing down or silencing that media outlet, and possibly others. Could a friend buy it? Could you bring in some legislation that shuts it out? How about making sure it loses its advertising? That is happening now. In Hungary, there are very few independent media outlets left, and the media that remain is pretty scared about what might happen to them. Hungarian journalists are moving to other countries to get the chance to write about the issues.

In China, President Xi Jinping has just increased the pressure on journalists who report for official outlets by insisting they take a knowledge test, which is very much like a loyalty test, before being given press cards.

Just today, as I sit here writing, I’ve switched on the radio to hear that the UK’s Conservative Party has made an official complaint to the TV watchdog over Channel 4’s coverage of the general election campaign (there was a debate last night on climate change where party leaders who didn’t turn up were replaced with giant blocks of ice). A party source told the Conservative-supporting Daily Telegraph newspaper: “If we are re-elected, we will have to review Channel 4’s public service broadcasting obligations. Any review would, of course, look at whether its remit should be better focused so it is serving the public in the best way possible.” In summary, they are saying they will close down the media that disagree with them.

This not very veiled threat is very much in line with the rhetoric from President Donald Trump in the USA and President Viktor Orbán in Hungary about the media knowing its place as more a subservient hat-tipping servant than a watchdog holding power to account. It’s also not so far from attitudes that are prevalent in Russia and China about the role of the media.

For those who might think that media freedom is a luxury, or doesn’t have much importance in their lives, I suggest they take a quick look at any country or point in history where media freedom was taken away, and then ask themselves: “Do I want to live there?”

Dictators know that control of the message underpins their power, and so does this generation of macho leaders. Getting the media “under control” is a high priority. Trump went on the offensive against journalists from the first minute he strode out on to the public stage. Brazil’s newish leader, President Jair Bolsonaro, knows it too. In fact, he got together with Trump on the steps of the White House to agree on a fightback against “fake news”, and we all should know what they mean right there. “Fake news” is news they don’t like and really would rather not hear.

New York Times deputy general counsel David McCraw told Index that this was “a very dark moment for press freedom worldwide”.

When the founders of the USA sat down to write the Constitution – that essential document of freedom, written because many of them had fled from countries where they were not allowed to speak, take certain jobs or practise their religion – they had in mind creating a country where freedom was protected. The First Amendment encapsulates the right to criticise the powerful, but now the country is led by someone who says, basically, he doesn’t support it. No wonder McCraw feels a deep sense of unease.

But when Trump’s team started to try to control media coverage, by not inviting the most critical media to press briefings, what was impressive was that American journalists from across the political spectrum spoke out for media freedom. When then White House press secretary Sean Spicer tried to stop journalists from The New York Times, The Guardian and CNN from attending some briefings, Bret Baier, a senior anchor with Fox News, spoke out. He said on Twitter: “Some at CNN & NYT stood w/FOX News when the Obama admin attacked us & tried 2 exclude us-a WH gaggle should be open to all credentialed orgs.”

The media stood up and criticised the attempt to allow only favoured outlets access, with many (including The Wall Street Journal, AP and Bloomberg) calling it out. What was impressive was that they were standing up for the principle of media freedom. The White House is likely to at least think carefully about similar moves when it realises it risks alienating its friendly media as well as its critics.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”And that’s the lesson for media everywhere. Don’t let them divide and rule you” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

And that’s the lesson for media everywhere. Don’t let them divide and rule you. If a newspaper that you think of as the opposition is not allowed access to a press briefing because the prime minister or the president doesn’t like it, you should be shouting about it just as hard as if it happened to you, because it is about the principle. If you don’t believe in the principle, in time they will come for you and no one will be there to speak out.

That’s the big point being made by Baier: it happened to us and people spoke up for us, so now I am doing the same. A seasoned Turkish journalist told me that one of the reasons the Turkish government led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was able to get away with restrictions on critical media early on, was because the liberal media hadn’t stood up for the principle in earlier years when conservative press outlets were being excluded or criticised.

Sadly, the UK media did not show many signs of standing united when, during this year’s general election campaign, the Daily Mirror, a Labour-supporting newspaper, was kicked off the Conservative Party’s campaign “battle bus”. The bus carries journalists and Prime Minister Boris Johnson around the country during the campaign. The Mirror, which has about 11 million readers, was the only newspaper not allowed to board the bus. When the Mirror’s political editor called on other media to boycott the bus, the reaction was muted. Conservative Party tacticians will have seen this as a success, given the lack of solidarity to this move by the rest of the media (unlike the US coverage of the White House incident).

The lesson here is to stand up for the principles of freedom and democracy all the time, not just when they affect you. If you don’t, they will be gone before you know it.

Rallying rhetoric is another tried and tested tactic. They use it to divide the public into “them and us”, and try to convert others to thinking they are “people like us”. If we, the public, think they are on our side, we are more likely to put the X in their ballot box. Trump and Orbán practise the “people like us” and “everyone else is our enemy” strategies with abandon. They rail against people they don’t like using words such as “traitor”.

Again in Hungary, people are put into the “outsiders” box if they are gay, women who haven’t had children or don’t conform to the ideas that the Orbán government stands for.

Dividing people into “them and us” has huge implications for our democracies. In separating people, we start to lose our empathy for people who are “other” and we potentially stop standing up for them when something happens. It creates divides that are useful for those in power to manipulate to their advantage.

The University of Birmingham’s Henriette van der Bloom recently co-published research pamphlet Crisis of Rhetoric: Renewing Political Speech and Speechwriting. She said: “I think there is a risk we are all putting ourselves and others into boxes, then we cannot really collaborate about improving our society. Some would say that is what is partly going on at the moment.” Looking forward, she saw one impact could be “a society in crisis, speeches are delivered, and people listen, but it becomes more and more polarising”.

But it’s not just the future, it’s today. We already see societies in crisis, with democratic values being threatened and eroded. This does not point to a rosy future. But there are some signs for optimism. In this issue, we also feature protesters who have campaigned and achieved significant change. In Romania, a mass weekly protest against a new law which would allow political corruption has ended with the government standing down; in Hungary, a new opposition mayor has been elected in Budapest.

Democracies need to remember that criticism and political opposition are an essential part of their success. We must hope they do.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on macho male leaders

Index on Censorship’s winter 2019 issue is entitled The Big Noise: How macho leaders hide their weakness by stifling dissent, debate and democracy

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”How macho leaders hide their weakness by stifling dissent, debate and democracy” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F12%2Fmagazine-big-noise-how-macho-leaders-hide-weakness%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at how male leaders around the world are using masculinity against our freedoms[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”111045″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/09/magazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Oct 2019 | News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”110170″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]“Every Hong Kong protester is my biggest inspiration. You guys think I am brave? Those young kids, 16 and 17 years old, are risking their lives at every protest. They are the people who inspire me, they are the people who motivate me to do more work to share their story with you guys.” These words, from the Chinese dissident artist known as Badiucao, were met with rapturous applause from the audience at the private screening of the new documentary about his life, China’s Artful Dissident.

The invitation-only screening was held at the Tate Exchange and hosted by Index On Censorship. Badiucao, who until recently had kept his identity a secret in an attempt to protect himself and his family from the Chinese government, was present, alongside the filmmaker Danny Ben-Moshe.

The film cannot fail to move and inspire. It documents Badiucao’s move into political activism after watching a documentary about the Tiananmen Square massacre, the details and death toll of which the Chinese government has done its best to suppress, and his move to Australia in 2009 to escape the censorship and artistic oppression in China.

The last part of the documentary shows the lead up to an exhibition of Badiucao’s work in Hong Kong. It ends on a heartbreaking note when the exhibition is cancelled following threats to Badiucao’s family in China. This was the reason Badiucao revealed his identity; it became clear that the Chinese government had already discovered it.

The screening was followed by a Q&A with Badiucao and Ben-Moshe, chaired by Martin Rowson, the political cartoonist and regular contributor to Index on Censorship magazine. Responding to a question about his safety in Australia, Badiucao described it as “a problematic country” and that he may have been naive to think he could entirely escape the influence of Beijing.

“Australia can be an example of how China is projecting its threat all over the world,” he said.

Addressing current counter-protests from the Chinese diaspora specifically, Badiucao said:

“You have to remember that when we grow up in China, we grow up with an entire machine of propaganda, it will take a very long time for people to walk out of this shadow.”

He expressed concern that people may view the Chinese population, the counter-protesters in particular, as brainwashed, aggressive nationalists who don’t deserve democracy.

“As a consequence, the far right will rise, xenophobia will rise, discrimination will rise, racism against China will rise. Ultimately this solution will not solve the problem, it just pushes the Chinese back to Beijing.”

Badiucao’s career goal, he explained, is to destroy censorship using art. He said: “I’m very proud and honoured that my work is recognised and used by the Hong Kong protesters.” He also said that his art is a way to record history to act as counterpoint to the Chinese government, who rewrite history.

Badiucao is now living in Australia and having revealed his identity, he is followed, sees strange cars outside his home and receives daily threats via social media. He made light of those that daily detract him.

“We call them 50 cent, because when they send me a death threat, they get 50 cent deposited into their bank accounts,” he said of China’s infamous trolls.

All of this is the price he pays for simply expressing himself through his art.

Click here to read more about Badiucao and to see an exclusive cartoon of his in the new magazine[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Like brothers in arms, they revel in the same set of characteristics. They share them, and their favourite ways of using them, on social media.

Like brothers in arms, they revel in the same set of characteristics. They share them, and their favourite ways of using them, on social media.