Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114690″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]“The Hungarian public’s access to sources of balanced news and information is in greater danger than ever before.” This was the stark warning that Index on Censorship, alongside 15 other organisations, delivered to Executive Vice-President of the European Commission Margrethe Vestager today.

After a decade of Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s rule, Hungary’s media landscape is in turmoil. Last month, 70 of the approximately 90 journalists working at Index.hu – which had been considered one of the last major independent news outlets in Hungary – resigned after the editor-in-chief was fired by the company’s CEO.

“For years, we’ve been saying that there are two conditions for the independent operation of Index: that there be no external influence on the content we publish or the structure and composition of our staff. Firing Szabolcs Dull has violated our second condition. His dismissal is a clear interference in the composition of our staff, and we cannot regard it any other way but as an overt attempt to apply pressure on Index.hu,” the departing journalists wrote in an open letter.

“Index was the most widely read news website in Hungary,” explained András Pethő in an interview with Index on Censorship. Pethő is co-founder and senior editor at Direkt36, a small investigative journalism outlet that focuses on reporting abuses of power. “It was one of the few remaining independent news websites in Hungary. It was a kind of hub on the Hungarian internet: a lot of people started their day by checking Index.”

“The organisation, the outlet itself is still here. The whole staff resigned but they hired new people. There’s a new leadership and we’ll see what that looks like, how they will cover news, and how independent they will be,” said Pethő. “What happened is bad for basically everyone who is interested in independent journalism in Hungary.”

Before founding Direkt36, Pethő had been a reporter and editor at Origo.hu, one of the largest online news outlets alongside Index. But in 2014, Origo.hu’s editor-in-chief was abruptly replaced after an investigation was published about lavish expenses claimed by Orban’s chief of staff. “Basically we went through a pretty similar story [to Index],” said Pethő. “The whole project – Direckt36 – was born as a response to the negative environment.”

What happened at Index and Origo are just two examples of the Hungarian government’s efforts to undermine independent media in the country. Index on Censorship has reported regularly on Orban’s attacks on the media and has been particularly concerned by events of the last six months fearing that the Covid-19 crisis is being used as a distraction to further curtail media freedom. In this period, we have received reports of journalists being barred from press conferences, alongside other attacks that we have documented on our map.

But despite the government’s ongoing and strategic efforts to punish critical media and reward government mouthpieces, the EU has yet to meaningfully intervene. As highlighted by the signatories of today’s letter to Vestager, such efforts have included the misuse of state aid, which has resulted in two complaints being logged with the European Commission in 2016 and 2018 respectively. The first complaint relates to Hungary’s public service broadcaster which, despite having long ceased to meet international standards due to its clear pro-government bias, continues to receive state funding. The second relates to the distribution of state advertising to media outlets in Hungary.

Although it was a market leader, Index.hu had received virtually no state advertising in the years prior to the mass resignations. At the same time, its main competitor – the now pro-government Origo.hu, benefitted heavily. As stated in today’s letter, “the goal of these efforts is clear: to financially weaken independent media and hamper the production and dissemination of critical news.”

Pethő says that Direkt36 are among the organisations feeling the squeeze. “When we launched it in 2015 and when we had a bigger story, those stories were often picked up by several online news outlets, a couple of TV channels, radio stations… so it could travel quite widely in the Hungarian media,” he said.

“That space has been shrinking gradually more and more and now when we publish a bigger piece maybe it’s picked up by a couple of news websites, maybe there is a radio interview, maybe one TV channel. But it’s much less than what we had three, four or five years ago.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Richard Patterson/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

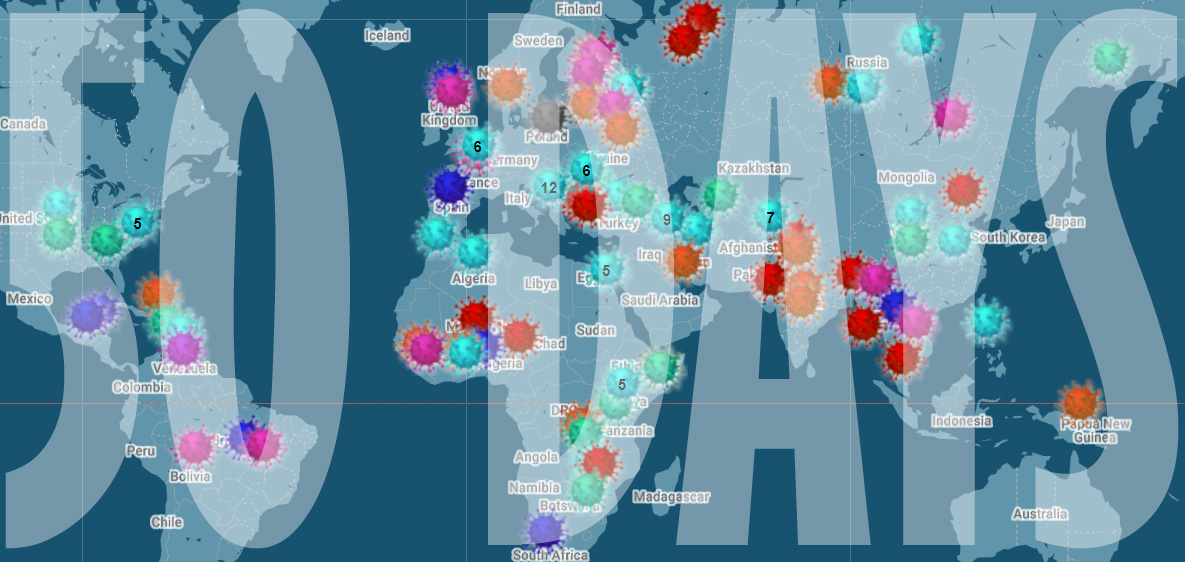

As we mark 50 days since we first started collating attacks on media freedom related to the coronavirus crisis, we’re horrified by the number of attacks we have mapped – over 150 in what is ultimately a short period of time.

We know that in times of crisis media attacks often increase – just look at what happened to journalists after the military coup in Egypt in 2013 and the failed coup against Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey in 2016. The extent of the current attacks, in democratic as well as authoritarian countries, has been a shock.

Our network of readers, correspondents, Index staff and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation have helped collect the more than 150 reports media attacks.

But these incidents are likely to be the very tip of the iceberg. When the world is in lockdown, finding out about abuses of power is harder than ever. Journalists are struggling to do their job even before harassment. How many more attacks are happening that we don’t yet know about? It’s a scary thought.

Rachael Jolley, editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship, said: “We are alarmed at the ferocity of some of the attacks on media freedom we are seeing being unveiled. In some states journalists are threatened with prison sentences for reporting on shortages of vital hospital equipment. The public need to know this kind of life-saving information, not have it kept from them. Our reporting is highlighting that governments around the world are tempted to use different tactics to stop the public knowing what they need to know.”

Index is alarmed that the attacks are not coming from the usual suspects. Yes, there have been plenty of incidents reported in Russia and the former Soviet Union, Turkey, Hungary and Brazil. At the same time there have been many incidents in countries you would not expect to see – Spain, New Zealand, Germany and the UK.

The most common incident we have recorded on the map are attacks on journalists – whether physical or verbal – and cases where reporters have been detained or arrested. There have been more than 30 attacks on journalists, with the source of many of these being the US President Donald Trump. He has a history of being combative with the press and decrying fake news even where the opposite is the case and the crisis has seen a ramped up attempt at excluding the media. During the crisis, he has refused to answer journalists’ questions, attacked the credentials of reporters and walked out from press conferences when he doesn’t like the direction they are taking.

We have also seen reporters and broadcasters detained and charged just for trying to tell the story of the crisis, including Dhaval Patel, editor of the online news portal Face of Nation in Gujarat, Mushtaq Ahmed in Bangladesh and award-winning investigative journalist Wan Noor Hayati Wan Alias in Malaysia.

Since we started the mapping project, we have highlighted other specific trends. Orna Herr has written about how coronavirus is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims. Jemimah Steinfeld wrote about how certain leaders are dodging questions while we have also looked at how freedom of information laws are being suspended or deadlines for information extended.

Although the map does not tell the whole story it does act as a record of these attacks. When this crisis is finally all over, it will allow us to ask questions about why these attacks happened and to make sure that any restrictions that have been introduced are reversed, giving us back our freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_btn title=”Report an incident” shape=”round” color=”danger” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fforms.gle%2Fhptj5F6ZvxjcaGLa7|||” css=”.vc_custom_1589455005016{border-radius: 5px !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Viktor Orbán Credit: European People’s Party/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán, leader of right-wing nationalist party Fidesz, has responded to the coronavirus crisis by pushing through sweeping emergency laws that have no time limit and have enormous potential to limit media freedom.

These laws essentially allow Orbán to rule by decree, which presents a huge threat to democracy and freedom of expression. While Index acknowledges that extraordinary measures need to be taken to protect lives, the passing of emergency laws of this nature for an indefinite time period was described in an Index statement as “an abuse of power”.

Under the emergency laws, journalists can be imprisoned for up to five years for publishing what the authorities consider to be falsehoods about the outbreak or measures taken to control it. But what exactly constitutes falsehoods is open to interpretation.

As Index notes, Hungary already has “one of the worst free speech records in Europe”. This further blow to journalists’ ability to report freely and objectively on the actions taken by the government is crippling for press freedom. It follows a pattern of state authorities infringing on press freedom under the guise of quashing “fake news” that Index has recorded happening globally in the wake of the crisis.

Transparency about the official numbers of those infected and those who have died from Covid-19 is critical for public safety. The scale of the outbreak will inform public behaviour and support for health services. Authoritarian regimes around the world such as North Korea and Turkmenistan have reported zero cases, the implausibility of which suggests censorship of the real figures by these countries’ despotic leaders.

Orbán is on the road to joining these leaders as, under the emergency laws, journalists are unable to hold the government to account over the accuracy of the data. Orbán has singular control of the public knowledge of the number of confirmed coronavirus cases, which, according to a government website, is 817 to date. See more here about this on the Index map tracking attacks on media freedom in Hungary.

Hungary’s neighbour Austria, which has a smaller population and recorded its first cases just 8 days before Hungary, has to date recorded 12,206 cases.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1586344862424-03642fb1-d46b-2″ taxonomies=”4157″][/vc_column][/vc_row]