Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Rory O’Neill is a Dublin-based stand-up comedian and self-described accidental activist for gay rights, who sees his duty as “to say the unsayable”.

O’Neill had been performing a comedy drag act under the name “Panti Bliss” for more than two decades when, over the course of one conversation in January 2014, he was thrust onto an international stage. While guest-starring on the Saturday night talk show of Ireland’s premier TV channel, he made reference to observable homophobia among certain Irish news figures. Pressed for names, he identified columnists John Waters and Breda O’Brien, as well as the Iona Institute, a socially conservative Catholic think tank campaigning against gay marriage, as examples of anti-gay attitudes.

RTÉ One and O’Neill were immediately threatened with legal action for alleged defamation. The TV company issued a full apology and paid six individuals €85,000 – with €40,000 allegedly going to Waters – of public money to settle the dispute. It also edited out the offending segment of the episode on its online player. The apology prompted almost a thousand complaints to the TV station and Pantigate, as the controversy came to be called, triggered countrywide debate.

The incident was brought up in both the Irish and European parliaments amid discussions of homophobia in Europe. Paul Murphy, a Socialist Party MEP for Dublin, used parliamentary privilege to denounce O’Neill’s detractors as homophobic, and to criticise RTÉ One’s attempts at appeasement.

The voices of columnists such as Waters, who called same-sex marriage a “satire of marriage”, and O’Brien, who has said that “equality must take second place to the common good”, have become more insistent as Ireland gears up for its referendum on gay marriage in May 2015. Early poll results suggest that the majority of voters will support the resolution for equal marriage rights.

Three weeks after the RTÉ One appearance, Panti appeared after a show at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin to deliver an impassioned ten-minute speech about pervasive low-level homophobia in Ireland. The speech rapidly garnered hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube, and attracted the support of Stephen Fry and Madonna, among others. Columnist Fintan O’Toole called it “the most eloquent Irish speech since Daniel O’Connell [a 19th-century Irish political leader] was in his prime”.

O’Neill channelled the events of early 2014 into his new stand-up set High Heels in Low Places, which was highly praised in reviews for fusing incisive political commentary and down-to-earth, traditonal drag-act humour. During anecdote-based performances, O’Neill has spoken about the difficulties he faced coming out in the late ’80s in a country where homosexuality was still a criminal act, as well as the emotional turmoil of being diagnosed with HIV in the mid-90s.

O’Neill becomes Panti Bliss every Saturday night at his Dublin-based LGBT-friendly bar, PantiBar. This year he has published a memoir, called Woman in the Making, and has been named one of Rehab’s People of the Year. After a successful indiegogo campaign raised €50,000, director Conor Horgan has begun work on a film about Panti, The Queen of Ireland, to be released in 2015.

This article was posted on 26 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

This week the Plain People of Ireland (both the physical and metaphorical place — more on that later) wailed, gnashed teeth, shook their fists at passing clouds and, of course, took to Twitter to express their horror, over a situation comedy.

Well, not an actual situation comedy. More an idea, that may turn into a script, that may, at some point, but probably not, turn into a comedy series. Still though…

It started harmlessly enough, in an end of year feature in the Irish Times (a newspaper not noted for sensationalism). Bright young things told of their plans for 2015. One, scriptwriter Hugh Travers, told the paper about his planned script for a sitcom called Hunger, which was in development stage with the UK’s Channel 4. The comedy would be based during the Irish famine. “I don’t want to do anything that denies the suffering that people went through,” said Travers, “but Ireland has always been good at black humour.”

Oh Hugh, how right you are. If there’s one thing everyone knows about us Irish, it’s our great sense of humour. We are, no doubt, a great bunch of lads when it comes to laughing.

But we are also, and let us be clear on this, a people with a profound sense of our own history; a nation carrying with us the struggle of generations and the ghosts of our patriot dead.

Or, to put it another way, we’ve got baggage. Playwright Brendan Behan said that: “Other people have a nationality. The Irish and the Jews have a psychosis.”

A large part of that baggage, that psychosis, comes from the great famine of the mid 19th century.

The famine of 1842-1847 was probably the bleakest period in Irish history. At least in population terms, the country has never really recovered. Over a million died and millions more emigrated.

Not that Ireland had been bread and roses before that. Over a century before, Jonathan Swift had addressed poverty and hunger in rural Ireland with his satirical pamphlet “A Modest Proposal” (“A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People From Being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public”, to give it its full title), which suggested a scenario where poor Irish people with large families should sell their children as food.

Even so, the 19th century famine was the worst of the worst, exacerbated by a government in London that was, at very, very least, negligent, and most certainly culpable. I will not get into a debate about whether it should be classified as a genocide or not, except to say that opinions either way on that judgment are too often based on what “side” one is on rather than evidence.

In any case, to get into that argument is to play into the hands of the brouhaha that followed Hugh Travers’ optimistic announcement of his plans in the Irish Times.

The fuss was kicked up by Niall O’Dowd, editor of Irish-American website Irish Central and, to judge by his extensive Wikipedia page, a very important man indeed.

New York-based O’Dowd wrote an article on his very important website, furiously denouncing the Channel 4 sitcom he couldn’t possibly have seen because it doesn’t exist.

It’s worth quoting the main thrust of his piece:

“What’s up next?? A sitcom on The Holocaust maybe with funny fat Nazis eating victims alive?

Or how about a comedy about Ebola with black kids dying on screen and doctors telling funny jokes about them?

‘Sure you are being way too sensitive,’ I can hear people say, ‘time to have a laugh about the Famine. Did you hear the one about the starving children? Some of them ate grass…Ha Ha Ha.”

Much like a homophobe denouncing gay sex, O’Dowd displays a remarkably vivid and well, dark imagination about what a comedy set during the famine might be: surely, he suggests, the thing that we are being asked to laugh at is the very worst thing you can dream of (Don’t get too smug about this point by the way; the converse of this could be that your relative lack of an outrage impulse stems from your relative lack of imagination. I know that’s true of me).

O’Dowd wonderfully went one further, writing another article for Irish Central in which he imagined the script for the proposed sitcom. Suffice to say, it was not funny, but not not funny in the way the author intended.

O’Dowd’s real problem, it seemed, was that Channel 4 was a British company making hay out of an Irish tragedy: he barely examined the fact that the originator of the script is an award-winning Irish author given an open brief. That would bring unwelcome complexity to the issue.

Last Monday, I was invited to discuss the issue on BBC Ulster’s Nolan show. I joked beforehand that the slot would degenerate into listing topics that we were and were not allowed to make comedy of. That was exactly what transpired, as my interlocutor, Irish commentator Jude Collins, began listing incidents and asking “Would you think that was funny?” — everything from 9/11 to the death of Ian Paisley (why the peaceful death of an old man was a tragedy on a par with the starvation of a million people was not made clear by Collins).

The problem with this line of thinking is that it’s not actually a line of thinking at all. It is mere positioning. Collins inadvertently demonstrated that once you start proscribing fit topics for comedy, you can’t stop. It’s always possible to find someone, somewhere who would be upset by practically any joke of substance. A caller into the show skewered Collins by pointing out he had stood against born-again Christians who had attempted to ban a comedy play based on the Bible (as reported by Index). Were they not offended? Did their feelings not count?

Those who raised their voice attempting to prevent the development of the famine script they couldn’t even have read — including the tens of thousands of Irish people at home and abroad who signed an online petition against the comedy — were simply parading their ignorance, much like the mullahs who condemned Salman Rushdie while boasting that they had not read the “blasphemous” Satanic Verses. They should think twice, or even once, before raising their hackles again.

This article was published on 9 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

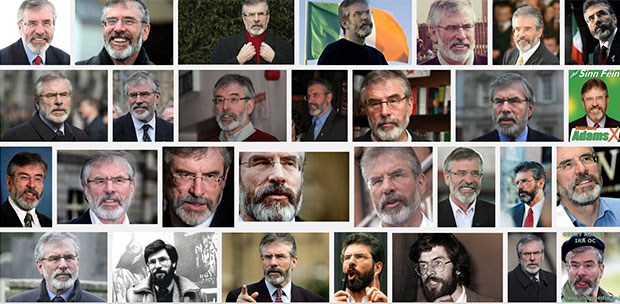

Gerry Adams is the leader of Sinn Féin, the party currently polling higher than any other in Ireland. Last week, Adams, who for many years had the very sound of his voice banned from the airwaves in both Ireland and Britain, due to his connections with the illegal Provisional IRA, told a funny little story at a fundraiser in New York.

Discussing one Irish newspaper’s hostility to his party, Adams told the assembled of how Michael Collins, the Irish War of Independence leader, had dealt with the Irish Independent:

“He went in, sent volunteers in, to the offices, held the editor at gunpoint, and destroyed the entire printing press. That’s what he did. Now I can just see the headline in the Independent tomorrow, I’m obviously not advocating that”, said Adams.

As with much half-remembered Republican mythology, this wasn’t the whole story. As Ian Keneally, author of The Paper Wall: Newspapers and Propaganda in Ireland, 1919-21, related in the Irish Times, the Irish Independent had been broadly sympathetic to the cause of Irish freedom throughout the War of Independence, while deploring individual acts of violence. In the case Adams alluded to, a group of IRA men had indeed entered the Irish Independent offices and threatened the editor, Timothy Harrington, after the paper described a failed IRA ambush as “a deplorable outrage”. The leader of the IRA grouping, Peadar Clancy, said that the newspaper had “endeavoured to misrepresent the sympathies and opinions of the Irish people”. While some damage was done to the Irish Independent’s printing presses, the paper did not shut down.

Ironically for Adams, given his invocation of the fabled Michael Collins, the Irish Independent found itself in deep trouble with British forces for publishing a letter by the IRA leader in December 1920. On that occasion, British “Auxiliaries” entered the newspaper’s offices and literally held a gun to a staff member’s head, warning the paper never to print anything by Collins again. The threat worked.

Historical rigour aside, Adams’s comments obviously didn’t find much favour among journalists. The World Association of Newspapers wrote to Adams calling on him “to retract these comments and to publicly affirm your abhorrence of all forms of violence against journalists”. Adams has refused to do so, citing the hypocrisy of attitudes to the Collins & Co war-of-independence era IRA and the modern (now, we are told, departed) Provisional IRA. In this, he may have a small point, though this is an issue for Irish society at large and not just the newspapers (this cartoon captures that problem neatly).

One could excuse Adams’s allusions as the work of the mind behind his famously quirky, often tongue-in-cheek Twitter account, but there are several background issues that make the whole thing a little uncomfortable.

Firstly, the newspaper group involved has lost two journalists to gunmen in the past 20 years: Veronica Guerin of the Sunday Independent, murdered by gangsters in 1996, and Martin O’Hagan of the Sunday World, shot by loyalist paramilitaries in 2001. Jokes about threats to the Independent News & Media journalists carry that baggage, even if unintended.

Secondly, Adams and his party are currently under scrutiny over an alleged IRA sexual abuse cover up. A woman named Maria Cahill – a relative of Provisional IRA founder Joe Cahill – claims that she was raped by an IRA member, and that the organisation subsequently attempted to cover up the crime. Cahill claims she raised the issue directly with Adams (who, it should be stated for the record, says he has never been a member of the IRA, but nonetheless is viewed as the leader of that particular strand of Irish republicanism), but that justice was not done. Adams’s has already faced criticism for the alleged cover up of his brother Liam’s paedophilic assaults on family members.

Thirdly, Ireland is a country on edge at the moment. The Fine Gael/Labour coalition government’s disastrous handling of proposed water metering and charges has led to previously rarely seen nationwide protests. Having almost cast the previously dominant Fianna Fáil party into oblivion in 2011, Irish voters had hoped they could put faith in a new government. But now, once again, they feel lied to by politicians who do not seem to have the wishes of the population at heart. The perception is that the new water metering system is just another assault on people who have suffered enough after years of boom, bust and bank bailouts.

Into this already toxic mix comes media mogul Denis O’Brien, owner of, among other outlets, the Irish Independent. It is widely believed that O’Brien is supportive of the new watering metering system as Irish Water will eventually be privatised, and he will buy it. O’Brien has a stake in Siteserv, the company contracted to install water meters.

It is not a huge leap to imagine that O’Brien’s papers may be enthusiastic about water charges, and perhaps unsympathetic to protesters. And it’s not difficult to imagine anger being turned against Independent group journalists. After pictures of a brick being thrown at a Garda [police] car during a water protest in Dublin last week were published by the Sunday Independent, many online claimed the image had been photoshopped by the mendacious “Sindo” . This was clearly untrue, but the rumours demonstrated the distrust of institutions, including the press, that now permeates Irish society, and from which upstart Sinn Fein stands most to gain. Former Sinn Féin publicity officer Danny Morrison subsequently tweeted the address of Independent Newspapers, along with a picture of a wall missing a brick. Was he adding to the conspiracy theory? Or was he suggesting violent action against the Independent, in classic I-know-where-you-live style? See how easily the close-up nature of Irish media, politics and public life can set the mind racing?

The government has now proposed new water measures, which it hopes will quell the unrest. But the anti-press, anti-politics rhetoric may have gone too far for that, and in the run up to the centenary of Ireland’s “revolutionary period” of 1916-1923, when romantic rebellion ruled all, little will be gained by any party attempting to present itself as the voice of a reasonable settlement.

This article was posted on 20 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

It was, apparently, the posting of a “blasphemous image” on Facebook that led an angry mob to burn down houses with children inside them.

It’s been suggested that it was a picture of the Kaaba, Islam’s holiest site, that provoked the mob in Gujranwala in Pakistan. They rallied last Sunday at Arafat colony, home of 17 families belonging to the Ahmadi sect. As police stood by, houses were looted and torched. At the end of the night, a woman in her 50s, Bushra Bibi, and her granddaughters Hira and Kainat, an eight-month-old baby, were dead. None of them had anything to do with the blasphemous Facebook post.

Was the image even blasphemous? In some ways, it doesn’t really matter. What matters was that it was posted by an Ahmadi, whose very existence is condemned by the Pakistani penal code.

Ahmadiyya emerged in India in the late 19th century. It is a small sect based on the belief that its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, was, in fact, the Mahdi of Muslim tradition. This teaching is rejected by Orthodox Sunni Islam.

In Pakistan, this means that being a member of the Ahmadiyya sect is dangerous. The law says you cannot describe yourself as Muslim. You cannot exchange Muslim greetings. You cannot describe your call to prayer as a Muslim call to prayer. You cannot describe your place of worship as a Masjid.

Any Ahmadi who “any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims” can be imprisoned for up to three years.

Ahmadis suffer disproportionately from Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, but they are not the only ones who suffer. Accusations of blasphemy are frequently levelled at members of other minorities and at mainstream Muslims too. Often, this is done out of sheer spite. Often it is done to settle scores.

As the New Statesman’s Samira Shackle has pointed out, amid the chaos and fear generated by the law, it’s often difficult to find out what people are actually supposed to have done, as media hesitate to repeat the alleged blasphemy lest they themselves be accused of the crime.

The fevered atmosphere created by the laws mean that to oppose them can be fatal. In Janury 2011, Punjab governor Salmaan Taseer was killed by his own bodyguard after he pledged to support a Christian woman, Aasia Bibi, who had been accused of the crime. Taseer’s assassin claimed that the governor had been an “apostate”. He was widely praised by the religious establishment. Three months later, Minority Affairs Minister Shahbaz Bhatti was killed, apparently because of his belief that the blasphemy law should be changed.

Meanwhile, an amendment proposed by Taseer’s colleague Sherry Rehman, which would have abolished the death penalty for blasphemy, was dropped. Rehman was posted to diplomatic service in the United States later that year, amid allegations that she herself had committed some kind of blasphemy.

The number of blasphemy cases is steadily rising, and Human Rights Watch recently claimed that 18 people are on death row after being found guilty of defaming the prophet Muhammad, though no one has as yet been executed.

The laws may seem archaic, but they are in fact utterly modern. While some of South Asia’s laws on religious offence date back to the Raj, the laws relating to the Ahmadi, and the law making insulting Muhammad a capital offence only emerged in the 1980s, as part of General Zia’s attempts to shore up his religious credentials.

The sad fact is this Pakistan’s new enthusiasm for blasphemy laws is not an international aberration. Nor is this a trend confined to confessional Islamic states.

Ireland’s 2009 Defamation Act introduced a 25,000 Euro fine for the publication of “blasphemous matter”. According to the Act , “a person publishes or utters blasphemous matter if—

(a) he or she publishes or utters matter that is grossly abusive or insulting in relation to matters held sacred by any religion, thereby causing outrage among a substantial number of the adherents of that religion, and

(b) he or she intends, by the publication or utterance of the matter concerned, to cause such outrage.”

Note how similar the wording is to the Pakistani law forbidding Ahmadis from offending Muslims. The Pakistani government repaid the compliment when, along with other members of the Organisation of Islamic Conference, it attempted to force the UN to recognise “religious defamation” as a crime, lifting text from the Irish act. Pakistan claimed, grotesquely, that criminalising blasphemy was about preventing discrimination. Cast your eyes back once again to how its blasphemy provisions treat Ahmadis.

Across Europe, more and more blasphemy cases are emerging. In January of this year, a Greek man was sentenced to 10 months for setting up a Facebook page mocking an Orthodox cleric. In 2012, Polish singer Doda was fined for suggesting that the Bible read like it was written by someone drunk and “smoking some herbs”. The trial of Pussy Riot in Russia was heavy with talk of sacrilege.

We tend to believe that the world is moving inexorably toward a secular settlement. The unintended upshot of this prevalent belief is that organised religions, even in countries like Pakistan, get to portray themselves as weak people who need to be protected from extinction, even as they wield power of life and death over people.

Religious persecution is real, and should be fought. Freedom of belief is a basic right. But blasphemy laws protect only power, and never people.

This article was posted on July 31, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org