24 Apr 2020 | Index in the Press

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine, Jemimah Steinfeld, writes in Eurozine about the violations the Index project to map media freedom during coronavirus is recording, and why this is so crucial.

“Mapping these abuses is of critical importance, not the least to let people and politicians know that we are watching and documenting. We need to increase awareness around the world about the challenges media professionals face during the coronavirus crisis, and to highlight the importance of media freedom.”

Read the full article here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Sep 2019 | News and features, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/KSxDIAuOCdI”][vc_column_text]Libraries are often the first place children experience the joy of reading. But what happens when a community attempts to censor the collection so that it reflects just one worldview?

Courtney Kincaid, assistant library director at North Richland Hills Library, told her harrowing story of being at the frontline of a battle over books at her library in Texas, in which she was followed from her work and did not eat out for fear people would spit in her food.

All of this because the library stocked two children’s books.

Kincaid was speaking as part of the event Three Ways Librarians Can Combat Censorship, which was organised by Sage Publishing as part of Banned Books Week. Kincaid was joined by two other panellists, Molly Dettmann, a school librarian at Norman North High School in Oklahoma, and Adriene Lim, dean of libraries at the University of Maryland. It was chaired by deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine Jemimah Steinfeld.

Kincaid said how in 2015 she was director of Hood County Library in Granbury, Texas, which she described as a ‘tea-party town’. When two children’s books, My Princess Boy by Cheryl Kilodavis and This Day in June by Gayle E. Pitman, were added to the shelves, a 21 week ordeal began for Kincaid as she defended the books against determined protestors.

Both books featured themes of diversity and acceptance of sexual difference, but were accused of promoting an LGBT lifestyle and perversion. Kincaid was faced with increasingly aggressive demands to remove the books. Some people wanted them burned. Kincaid said how she became a pariah in her town. She feared eating in restaurants in case people spat in her food. A state senator contacted her to admonish her for her fight to keep the books in the library. Kincaid attempted to reach a compromise by moving the books to the adult non-fiction section, but found this did not satisfy the protestors. She said: “They cared about their agenda and their agenda only, and it was anti-LGBT.” On 13 October 2015 the library won a legal battle for the books to remain.

Kincaid had since moved out of Granbury, Texas and was awarded for her efforts to protect the collection in Hood County Library with an I Love My Librarian award in 2015. She told the panel that the lesson she learned from her experience is to never try to find a middle ground with those attempting to censor. Her advice to librarians feeling pressure to self-censor: “Don’t be scared of what would happen. If you think your community needs a book, buy it. Stand your ground.”

Dettman, who herself is familiar with battles over which books should be on library shelves, highlighted her concerns over self-censorship which she said is widespread amongst librarians. She emphasised her belief that a school library should be a safe and welcoming place for all children and encouraged teachers to stock the library with an inclusive range of books. “Your kids deserve that so much. They need it, you have to remember that,” said Dettman.

She said books can transform lives, with it therefore being crucial to therefore have a library stocked with a very broad mix of books.

Lim spoke of when a mural was vandalised at the library in the University of Oregon when she was dean of libraries there. The mural depicted what Lim described as a white male supremacist narrative about the building of civilisation. Whilst not personally agreeing with the sentiment of the mural, Lim saw it as historical artefact and integral to the library’s original architectural design. She said that open and honest sharing of perspectives is a good thing because when voices are oppressed, when dialogues are shut down, “it is those with less power who will suffer the most.”

“If people pick and choose which historical perspectives can be displayed according to current values, where does that leave libraries?” Steinfeld added.

While the webinar was held as part of Banned Books Week, Dettman urged everyone to celebrate books and continue to fight against censorship in libraries throughout the year. “Don’t wait for Banned Books Week. Do it all the time,” she said. [/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1569574933173-1fc994b1-338d-3″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Feb 2018 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Devils’ Dance by Hamid Ismailov

Hamid Ismailov is an Uzbek journalist and writer who was forced to flee Uzbekistan in 1992 due to what the state dubbed ‘unacceptable democratic tendencies’. A writer whose works are banned in his home-country, he is the author of numerous books including acclaimed Russian-language novels, The Dead Lake, The Railway and The Underground. The Devil’s Dance – translated by Donald Rayfield and published by Tilted Axis – is the first of his Uzbek-original novels to appear in English.

The Devils’ Dance weaves the stories of Queen Oyxon in nineteenth-century Turkestan and Abdulla Qodiriy, one of the best writers of twentieth-century Uzbekistan. When imprisoned by the NKVD in Tashkent, Qodiriy attempts to mentally reconstruct his novel about the famed Uzbek queen, a victim to the forces of the Great Game – the battle for supremacy over Central Asia between the British and Russian empires.

The Devils’ Dance brings to life the extraordinary culture of 19th century Turkestan, a world of lavish poetry recitals, brutal polo matches, and a cosmopolitan and culturally diverse Islam rarely described in western literature. Hamid Ismailov’s virtuosic prose recreates this multilingual milieu in a digressive, intricately structured novel, dense with allusion, studded with quotes and sayings, and threaded through with modern and classical poetry.

Join Hamid and Donald as they speak to journalist Rosie Goldsmith about this masterful marriage of contemporary international fiction and the Central Asian literary traditions. With a short introduction by Jemimah Steinfeld, Deputy Editor of the Index on Censorship.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”98077″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”98078″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”98079″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”88892″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Hamid Ismailov is a journalist and writer who was forced to flee Uzbekistan in 1992 due to what the state called ‘unacceptable democratic tendencies’. He came to the United Kingdom, where he took a job with the BBC World Service. Several of his Russian-original novels have been published to great acclaim (The Dead Lake was named Independent Book of the Year and Guardian Readers Book of the Year in 2014). He is a former BBC Writer in Residence and BBC Uzbek correspondent.

Donald Rayfield is a professor of Russian and Georgian at Queen Mary University of London. He has written books about Russian and Georgian literature, and about Joseph Stalin and his secret police, and translated Georgian and Russian poets and prose writers. He is also a series editor for books about Russian writers and intelligentsia.

Rosie Goldsmith is an award-winning journalist specialising in arts and current affairs, in the UK and abroad. In 20 years on the BBC staff she travelled the world, covering events such as the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of apartheid in South Africa, presenting flagship BBC programmes Front Row and Crossing Continents. Rosie speaks several languages and has lived in Germany, Africa and the USA. Today she combines broadcasting and arts journalism with presenting and curating cultural events and festivals in Britain and overseas. Rosie has interviewed many of the great names in culture and current affairs. She is founder of the European Literature Network and helped launch European Literature Night at the British Library in 2009 (now an annual event); for the European Commission she created The Language of Italian Fashion & Food; she originated the Dutch-UK festival High Impact, and, for Southbank Centre, Syria Speaks and Greece Is the Word.

Jemimah Steinfeld has lived and worked in both Shanghai and Beijing where she has written on a wide range of topics, with a particular focus on youth culture, gender and censorship. She is the author of the book Little Emperors and Material Girls: Sex and Youth in Modern China, which was described by the FT as “meticulously researched and highly readable”. Jemimah has freelanced for a variety of publications, including The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Vice, CNN, Time Out and the Huffington Post. She has a degree in history from Bristol University and went on to study an MA in Chinese Studies at SOAS.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_column_text]This event is in partnership with:[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”98081″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://www.pushkinhouse.org/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Thursday, April 5, 2018, 7:00-8:30 PM

Where: Pushkin House, 5A Bloomsbury Square, London WC1A 2TA Map

Tickets: From £7 via Pushkin House

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Dec 2015 | Asia and Pacific, China, Magazine, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This is an extract from an article in the Winter 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. You can read the article in full here.

The streets of Dongguan in southern China have been quiet of late. In the past, China’s city of sin would hum to the sound of late-night karaoke bars offering more than just an innocent sing-along. Now these establishments have been forced underground or driven out of business entirely. Their chances of a future are not looking good. On 1 January 2016, new regulations will come into effect that dictate appropriate behaviour for the Communist Party’s 88 million members. As part of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, the new rules explicitly ban the trading of power for sex, money for sex, and adultery – but these are the foundations of business in Dongguan.

“In Dongguan, whose reputation, if not economy, practically rests on its skin trade, I’m told by several sources that the trade remains mostly out of sight nearly two years after a television report [led to]a sweeping crackdown,” said Robert Foyle Hunwick, a writer who has visited the city many times to research his forthcoming book The Pleasure Garden: China’s Hidden World of Sex, Drugs and the Super-Rich.

Dongguan is not the only city suffering from this campaign against smut – it has been lights out for many brothels across China. Nor is this crackdown limited to China’s Communist party members, as the January 2016 regulations imply. Instead, it forms part of a broader crackdown on China’s sex industry that has been underway since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012.

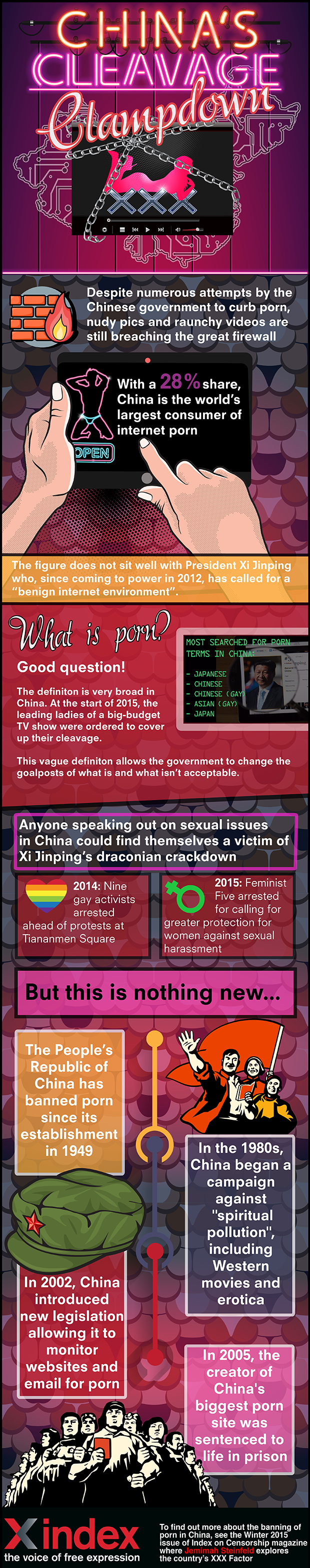

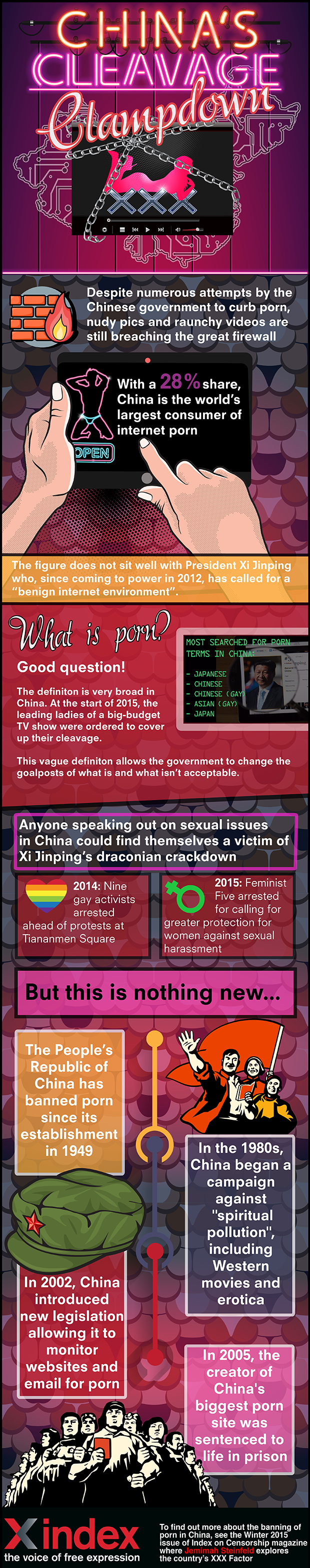

Enemy number one is internet pornography. In the most recent statistics, from 2014, China accounts for up to 28% of the world’s porn consumption, taking the global lead. It’s a statistic that does not sit well with Xi. Shortly into his term in power, he launched his first anti-pornography crusade, calling for a “benign internet environment”. An attempt was made to clear China’s internet of anything verging on pornography. A similar initiative was launched this summer, following the release of a video featuring a couple having sex in a Uniqlo store. It was the usual drill: sites were blocked or removed and anyone caught facilitating the production or distribution of pornography was arrested.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]