22 Jan 2020 | News and features, Volume 48.04 Winter 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In the winter 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley argues that a new generation of democratic leaders is actively eroding essential freedoms, including free speech” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Like brothers in arms, they revel in the same set of characteristics. They share them, and their favourite ways of using them, on social media.

Like brothers in arms, they revel in the same set of characteristics. They share them, and their favourite ways of using them, on social media.

From Orbán to Trump and from Bolsonaro to Johnson, national leaders who want to dismiss analysis with a personalised tweet, and never want to answer a direct question, have come to power – and are using power to silence us. They like to think of themselves as strongmen but what, in fact, they are doing is channelling the worst kind of machismo.

For toughness, read intolerance of disagreement. They are extremely uncomfortable with public criticism. They would rather hold a Facebook “press conference” where they are not pressed than one where reporters get to push them on details they would rather not address. Despite running countries, they try to pretend that those who hold them to account are the elite who the public should not trust.

While every generation has its “tough” leaders, what’s different about today’s is that they are everywhere, and learning, copying and sharing their measures with each other – aided, of course, by the internet, which is their ultimate best friend. And this is not just a phenomenon we are seeing on one continent. Right now these techniques are coming at us from all around the globe, as if one giant algorithm is showing them the way. And it’s not happening just in countries run by unelected dictators; democratically elected leaders are very firmly part of this boys’ club.

Here are some favoured techniques:

If you don’t like some media coverage, you look at ways of closing down or silencing that media outlet, and possibly others. Could a friend buy it? Could you bring in some legislation that shuts it out? How about making sure it loses its advertising? That is happening now. In Hungary, there are very few independent media outlets left, and the media that remain is pretty scared about what might happen to them. Hungarian journalists are moving to other countries to get the chance to write about the issues.

In China, President Xi Jinping has just increased the pressure on journalists who report for official outlets by insisting they take a knowledge test, which is very much like a loyalty test, before being given press cards.

Just today, as I sit here writing, I’ve switched on the radio to hear that the UK’s Conservative Party has made an official complaint to the TV watchdog over Channel 4’s coverage of the general election campaign (there was a debate last night on climate change where party leaders who didn’t turn up were replaced with giant blocks of ice). A party source told the Conservative-supporting Daily Telegraph newspaper: “If we are re-elected, we will have to review Channel 4’s public service broadcasting obligations. Any review would, of course, look at whether its remit should be better focused so it is serving the public in the best way possible.” In summary, they are saying they will close down the media that disagree with them.

This not very veiled threat is very much in line with the rhetoric from President Donald Trump in the USA and President Viktor Orbán in Hungary about the media knowing its place as more a subservient hat-tipping servant than a watchdog holding power to account. It’s also not so far from attitudes that are prevalent in Russia and China about the role of the media.

For those who might think that media freedom is a luxury, or doesn’t have much importance in their lives, I suggest they take a quick look at any country or point in history where media freedom was taken away, and then ask themselves: “Do I want to live there?”

Dictators know that control of the message underpins their power, and so does this generation of macho leaders. Getting the media “under control” is a high priority. Trump went on the offensive against journalists from the first minute he strode out on to the public stage. Brazil’s newish leader, President Jair Bolsonaro, knows it too. In fact, he got together with Trump on the steps of the White House to agree on a fightback against “fake news”, and we all should know what they mean right there. “Fake news” is news they don’t like and really would rather not hear.

New York Times deputy general counsel David McCraw told Index that this was “a very dark moment for press freedom worldwide”.

When the founders of the USA sat down to write the Constitution – that essential document of freedom, written because many of them had fled from countries where they were not allowed to speak, take certain jobs or practise their religion – they had in mind creating a country where freedom was protected. The First Amendment encapsulates the right to criticise the powerful, but now the country is led by someone who says, basically, he doesn’t support it. No wonder McCraw feels a deep sense of unease.

But when Trump’s team started to try to control media coverage, by not inviting the most critical media to press briefings, what was impressive was that American journalists from across the political spectrum spoke out for media freedom. When then White House press secretary Sean Spicer tried to stop journalists from The New York Times, The Guardian and CNN from attending some briefings, Bret Baier, a senior anchor with Fox News, spoke out. He said on Twitter: “Some at CNN & NYT stood w/FOX News when the Obama admin attacked us & tried 2 exclude us-a WH gaggle should be open to all credentialed orgs.”

The media stood up and criticised the attempt to allow only favoured outlets access, with many (including The Wall Street Journal, AP and Bloomberg) calling it out. What was impressive was that they were standing up for the principle of media freedom. The White House is likely to at least think carefully about similar moves when it realises it risks alienating its friendly media as well as its critics.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”And that’s the lesson for media everywhere. Don’t let them divide and rule you” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

And that’s the lesson for media everywhere. Don’t let them divide and rule you. If a newspaper that you think of as the opposition is not allowed access to a press briefing because the prime minister or the president doesn’t like it, you should be shouting about it just as hard as if it happened to you, because it is about the principle. If you don’t believe in the principle, in time they will come for you and no one will be there to speak out.

That’s the big point being made by Baier: it happened to us and people spoke up for us, so now I am doing the same. A seasoned Turkish journalist told me that one of the reasons the Turkish government led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was able to get away with restrictions on critical media early on, was because the liberal media hadn’t stood up for the principle in earlier years when conservative press outlets were being excluded or criticised.

Sadly, the UK media did not show many signs of standing united when, during this year’s general election campaign, the Daily Mirror, a Labour-supporting newspaper, was kicked off the Conservative Party’s campaign “battle bus”. The bus carries journalists and Prime Minister Boris Johnson around the country during the campaign. The Mirror, which has about 11 million readers, was the only newspaper not allowed to board the bus. When the Mirror’s political editor called on other media to boycott the bus, the reaction was muted. Conservative Party tacticians will have seen this as a success, given the lack of solidarity to this move by the rest of the media (unlike the US coverage of the White House incident).

The lesson here is to stand up for the principles of freedom and democracy all the time, not just when they affect you. If you don’t, they will be gone before you know it.

Rallying rhetoric is another tried and tested tactic. They use it to divide the public into “them and us”, and try to convert others to thinking they are “people like us”. If we, the public, think they are on our side, we are more likely to put the X in their ballot box. Trump and Orbán practise the “people like us” and “everyone else is our enemy” strategies with abandon. They rail against people they don’t like using words such as “traitor”.

Again in Hungary, people are put into the “outsiders” box if they are gay, women who haven’t had children or don’t conform to the ideas that the Orbán government stands for.

Dividing people into “them and us” has huge implications for our democracies. In separating people, we start to lose our empathy for people who are “other” and we potentially stop standing up for them when something happens. It creates divides that are useful for those in power to manipulate to their advantage.

The University of Birmingham’s Henriette van der Bloom recently co-published research pamphlet Crisis of Rhetoric: Renewing Political Speech and Speechwriting. She said: “I think there is a risk we are all putting ourselves and others into boxes, then we cannot really collaborate about improving our society. Some would say that is what is partly going on at the moment.” Looking forward, she saw one impact could be “a society in crisis, speeches are delivered, and people listen, but it becomes more and more polarising”.

But it’s not just the future, it’s today. We already see societies in crisis, with democratic values being threatened and eroded. This does not point to a rosy future. But there are some signs for optimism. In this issue, we also feature protesters who have campaigned and achieved significant change. In Romania, a mass weekly protest against a new law which would allow political corruption has ended with the government standing down; in Hungary, a new opposition mayor has been elected in Budapest.

Democracies need to remember that criticism and political opposition are an essential part of their success. We must hope they do.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on macho male leaders

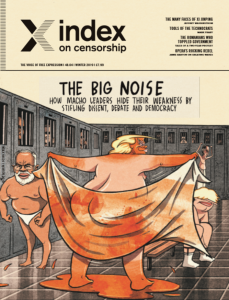

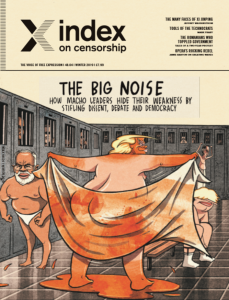

Index on Censorship’s winter 2019 issue is entitled The Big Noise: How macho leaders hide their weakness by stifling dissent, debate and democracy

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”How macho leaders hide their weakness by stifling dissent, debate and democracy” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F12%2Fmagazine-big-noise-how-macho-leaders-hide-weakness%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at how male leaders around the world are using masculinity against our freedoms[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”111045″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/09/magazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Jan 2020 | Journalism Toolbox Arabic

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Justin Morgan/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

لقد شاع مؤخرّا استخدام أجهزة الكمبيوتر لتوليد تقارير إخبارية محلية. يسأل مارك فراري ما إذا كان المزيد من الأتمتة هو الطريقة الوحيدة للبقاء على قيد الحياة في هذه الصناعة

إذا قرأتَ إحدى الصحف هذا الأسبوع، فإنه يحتمل أن بعض التقارير الإخبارية التي شاهدَتها لم يقم بكتابتها صحفي بشري بل تمت كتابتها من قبل آلة. إذ يستخدم الناشرون بشكل متزايد “صحافيين آليين” لتوليد تقارير بسيطة كان يكتبها صغار الصحافيين، والتي يمكن الآن كتابتها عن طريق إدخال البيانات في قالب قصة قياسي. الحجة هي إنه إذا كان بالإمكان إراحة الصحفيين من كتابة التقارير الروتينية، فانه يمكنهم قضاء وقتهم بشكل أكثر إفادة، ومحاسبة أصحاب النفوذ والسلطة بشكل أكبر. لكن المتشائمون يقولون بأن الوسائل الاعلامية، التي يتم ادارتها بشكل متزايد من قبل المحاسبين عوضا عن المبدعين، يحاولون ببساطة خفض التكاليف.

يقول رئيس تحرير بلومبرج نيوز جون مكلثويت إن ربع المحتوى الذي أنتجته شركة الأخبار العملاقة لديه فيها قدر من الأتمتة. وهو يستخدم نظامًا يدعىئ Cyborg “سايبورغ”، الذي يقوم بتحليل أرقام أرباح أي شركة في اللحظة التي تظهر فيها، لإنتاج ليس فقط عناوين الأخبار العاجلة، بل أيضا، وفي بضع ثوانٍ، تقرير صغير يحتوي على الكثير من الأرقام والسياق المصاحب لها. وهو ليس الوحيد الذي يستخدم مراسلين آليين. قامت واشنطن بوست بتطوير روبوت يسمى Heliograf “هيليوغراف”، الذي يولد تلقائيًا تقاريراً من نتائج المباريات الرياضية أيضاً.

تقول ميريديث بروسارد ، أستاذة مساعدة في معهد آرثر كارتر للصحافة بجامعة نيويورك، إنه في حين قد تكون تقارير الأرباح ملائمة للأتمتة، فإن أنواع الأخبار الأخرى ليست كذلك. لكن في الحقيقة، فإن إمكانات الذكاء الصناعي في كتابة أكثر من مجرد قصص إخبارية نموذجية بسيطة هي بالفعل معنا اليوم. قامت مبادرة يمولها البليونير إيلون ماسك باسم OpenAI “الذكاء الصناعي المفتوح” بتطوير محرك توليد نصوص يعمل من خلال الذكاء الصناعي باسمGPT-2 . تم تدريب المحرك من خلال تغذيته بالملايين من صفحات النص من الويب، وهو قادر على التنبّؤ بالكلمة التالية في أي جزء من النص ويمكنه كتابة الأخبار المزيّفة تزييفاً عميقاً “ديب فايك”. لا يمكن تمييز التقارير هذه، بالعين المجردة، عن تلك التي يكتبها صحفيون حقيقيون. وتقول الشركة إنها تشعر بقلق بالغ إزاء احتمال إساءة استخدام هذه التكنولوجيا لدرجة أنها قرّرت أن تمتنع عن نشر نتائج أبحاثها قبل فهم آثارها بشكل أكمل.

تعمل بروسارد، عالمة الكمبيوتر التي تحوّلت إلى صحافة البيانات، في مفترق الطرق بين الذكاء الاصطناعي والعمل الصحفي. قام فريقها بتطوير أداة تعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي تسمّى “بايليويك” Bailiwick، والتي ساعدت في توليد صور بيانية بناء على احصائيات عن تمويل الحملات الانتخابية الأمريكية عام ٢٠١٦. تقول بروسارد إن تحضير التحقيق الاستقصائي ذات الجودة العالية قد يستغرق سنوات ويتطلب الكثير من تحليل المستندات، بكلفة قد تصل الى الملايين من الدولارات وتضيف: “مشاريعي غير مكلفة بالمقارنة. وهذا شيء مهم لتحقيق الابتكار “.

لكن بروسارد لا تؤمن بأن الذكاء الاصطناعي سيحل محل الصحفيين. تقول: “هناك فكرة أن التكنولوجيا هي دائمًا الحل الأفضل – أسمي ذلك الشوفينية التكنولوجية …هناك فكرة تقول بأنه يمكننا استخدام عدد أقل من المراسلين ويمكنهم معرفة كل شيء من خلال وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي. لقد ثبت أن ذلك غير صحيح “.

يرى الكثيرون أن دور الذكاء الاصطناعي هو كأداة لمساعدة الصحفيين بدلاً من استبدالهم. بالنسبة لأولئك الذين يعملون في الصحافة المحلية، حيث يتناقص عدد الصحف بمعدل غير مسبوق، فقد يمثل ذلك طريقة لتجنب الانقراض. يقول توبي أبيل، كبير مسؤولي التكنولوجيا في شركة كرزانا، وهي شركة تختص بتزويد ناشري الأخبار المحليين بأدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي: “ان نموذج الإعلانات أًصبح عديم الفائدة بالنسبة للصحافة المحلية بعد ظهور وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي. نحن نرى فرصة لنماذج تمويل جديدة مع التركيز أكثر على قيمة وثقة القارئ. بدلا من أن يدفع المعلن، يدفع القارئ”. ويضيف: “دور الذكاء الاصطناعي هو أن يأخذ المهمّات المكرّرة في الصحافة ومحاولة استبدالها من خلال الحلول الرخيصة والسريعة التي تخفف عن كاهل الصحفيين”.

كرزانا – والاسم هو مستوحى من كلمة باللغة السنسكريتية تشير على فعل العثور على اللؤلؤ أو جس النبض البشري – هي أداة “تحاول السماح للناس بوضع إصبعهم على ما يجري والعثور على المعلومات”. فهي تجمع عشرات الآلاف من خلاصات المحتوى في الوقت الفعلي – من وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي، ومدونات الشرطة، ومحاضر الحكومة المحلية – وتجمعها باستخدام أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي، ومعظمها ملك الشركة التي طوّرتها. يقول أبيل: “يخبرنا الصحفيون أنهم يريدون أن يعرفوا متى يتحدث شخص ما عن نوع معين من الجرائم في برمنغهام، على سبيل المثال”. لكنه يرفض المبادرات التي تهدف إلى استبدال الصحفيين البشر بمراسلين آليين، قائلاً: “كانت النتيجة رديئة وسطحية وتركّز على اجتذاب النقرات عندما تم تجريب هذه المقاربة. وليست الصحف الكبيرة وحدها التي تستخدم كرزانا. مثلا، يقوم موقع “ذا ويست بريدجفورد واير” The West Bridgford Wire أيضا باستخدام الأداة، وهو موقع إخباري يركّز على الأخبار المحليّة يقع مقره في نوتنغهام ويتلقى ما يصل إلى مليون زيارة كل شهر. يقول أبيل: “لقد تضاعف عدد القراء أربعة أضعاف في الأشهر الـ ١٢ الماضية من خلال التمكن من العثور على مصادر صحافية للتقارير مع شخص واحد فقط يقوم بالصحافة الاستقصائية العميقة. يبدو أن هذا هو المستقبل.

يستخدم العديد من الناشرين أدوات تجميع المحتوى مثل Tweetdeck ، لكن محرر موقع “ذا واير”، بات غامبل، يقول أن كرزانا هي أداة أذكى. يشرح قائلاً: “لديها طريقة سحرية لتنظيف الأشياء. معظم الأشياء التي تظهر في الأداة هي مفيدة. “يستخدم غامبل كرزانا على أساس يومي ويقول إن الفائدة الرئيسية هي أن التقارير تظهر عند نشرها، وليس فقط عند تغريدها، مما يسمح له أن يسبق الآخرين. ويقول إن الموقع يتعاقد باستمرار مع معلنين جدد يعجبهم المحتوى الجديد والملائم الذي ينشره.

يأتي بعض التمويل لزيادة استخدام أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي في الصحافة المحلية والإقليمية من شركتين من الشركات التي كانت السبب في إخراج ناشري الأخبار المحليين من العمل في المقام الأول، على الرغم من استفادتها من محتوى هؤلاء الناشرين، أي فيسبوك وغوغل. في يناير ٢٠١٧، تم إطلاق مشروع فيسبوك للصحافة “لإقامة علاقات أقوى بين فيسبوك وصناعة الأخبار”. كانت أهدافها تتضمّن تطوير منتجات إخبارية تعاونية وتوفير التدريب والأدوات لكل من الصحفيين والأفراد. ومنذ ذلك الحين قام فيسبوك بتنظيم العديد من المؤتمرات حول الأدوات الإلكترونية “هاكاثون” (حيث يجتمع المطورون لإنشاء البرمجيات) بحضور المنظمات الإخبارية، والتي يقوم بعضها بتطوير أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي الخاصة بها. تم إطلاق مبادرة أخبارغوغلGoogle News Initiative في العام التالي والتي تهدف إلى “تمكين المؤسسات الإخبارية من خلال الابتكار التكنولوجي”. يقول أبيل، من كرزانا: “أعتقد أن هناك خطراً في أن يتم استخدام (التمويل) كأداة لضمان أن تستمر الصحافة المحلية في عدم جني الأموال. يجب استخدامه عوضا عن ذلك كخطوة انطلاق. ان ضخ رأس المال طريقة رائعة لحل مشكلة عدم القدرة على الانطلاق في العمل للوصول الى الصحافة المحلية المستدامة”.

“أحد المشاريع التي تلقت تمويلًا من غوغل هو أداة ذكاء اصطناعي تُسمّى “إنجكت” Inject ، والتي بناها فريق بقيادة نايل مايدن، أستاذ الإبداع الرقمي في كلية كاس للأعمال في لندن. هذه الأداة هي مثل محرك البحث، وتقوم بإنشاء فهرس من مئات المصادر كل يوم، وهذا يحتوي الآن على أكثر من ١٠ ملايين تقرير اخباري.

يقول مايدن: “لقد كتبنا عددًا من الخوارزميات – يمكنك تسميتها بحثاً إبداعياً. يمنحك غوغل ما تريده بالضبط. إذا وضعت شيئاً ما في أداتنا، فستأخذ ما تكتبه وتبحث عن شيء مماثل له ولكنه مختلف”. تركز أداة إنجكت على إيجاد زاوية تغطية للصحفيين، سواء كانت ذلك البيانات أو الزاوية البشرية أو التقارير الطويلة أو شيء غريب أو فكاهي. لإنشاء الخوارزميات التي تحرّك إنجكت، عمل فريق مايدن مع الصحفيين والسياسيين المحليين ذوي الخبرة لتقييم التقارير الإخبارية بسحب معايير مختلفة واستخدام البيانات لمعرفة ما الذي يجعل التقرير “جيداً”. “نحن لا نجعل الصحفيين أكثر إبداعًا؛ نحن نحاول جعلهم مبدعين بشكل أسرع “.

ويقول فنسنت بيريجني، الرئيس التنفيذي للرابطة العالمية لصحف الأخبار وناشري الأخبار، بأن الذكاء الاصطناعي قد يوفر شريان حياة للبعض، وطريقة جديدة في العمل للبعض الآخر. يقول: “في إفريقيا، هناك اهتمام قوي بالذكاء الاصطناعي بسبب الموارد المحدودة لديهم. إن الذكاء الاصطناعي فرصة للتحسين والنمو”. وهو يعتقد أن التحدي الأكبر الذي يواجه تبني الذكاء الاصطناعي على نطاق واسع ليس التكنولوجيا، بل “إنه يتعلق بتغيير مسار العمل وثقافة مؤسستك. عنق الزجاجة هو الإدارة”.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]مارك فراري هو صحفي ومؤلف. قام مؤخرًا بنشر De / Cipher، وهو دليل عملي وتاريخي عن التشفير، وهو يعمل على سرد قصة ظهور شركة التكنولوجيا Psion[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Jan 2020 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Imagen: Justin Morgan/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Generar noticias locales por ordenador es una práctica habitual. Mark Frary plantea si la automatización es la única manera que tiene la industria de sobrevivir”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Si ha leído el periódico en la última semana, es posible que algunas de las noticias que viera no las haya escrito un periodista de carne y hueso, sino una máquina.

Los editores están utilizando “reporteros robot” con cada vez más frecuencia para generar las noticias de menos dificultad, que solían redactar los periodistas novatos, pero que ahora pueden crearse simplemente introduciendo datos en una plantilla de noticia estándar.

Quienes defienden la práctica argumentan que, al librarse de tener que redactar las mismas noticias una y otra vez, los periodistas pueden aprovechar el tiempo de forma más productiva y, por ejemplo, obligar a los poderosos a responder por sus actos. Los más cínicos oponen que los medios, en los que los contables abundan cada vez más que los puestos creativos, lo que hacen es intentar recortar gastos.

John Micklethwait, redactor jefe de Bloomberg News, afirma que una cuarta parte del contenido que produce el gigante de las noticias está automatizado en cierto grado.

La compañía utiliza un sistema llamado Cyborg que “disecciona los ingresos de una empresa en cuanto aparecen y no solo produce titulares al instante, sino que también, en cuestión de segundos, ofrece lo que es de hecho un minianálisis de las cifras con un montón de contexto”.

Y Bloomberg no son los únicos que utilizan reporteros robots. El Washington Post ha desarrollado un bot llamado Heliograf que genera noticias automáticamente a partir de resultados deportivos.

Meredith Broussard, profesora auxiliar del Instituto Arthur L Carter de Periodismo de la Universidad de Nueva York, apunta que, mientras que las noticias sobre ingresos se prestan a la automatización, otros tipos de noticias, no.

El potencial de la IA para escribir algo más que una noticia a partir de plantillas ya es una realidad. Una iniciativa llamada OpenIA, financiada por Elon Musk, ha desarrollado un procesador de texto basado en inteligencia artificial al que han llamado GPT-2. La IA, que ha aprendido a partir del texto de millones de páginas web, predice la siguiente palabra de un fragmento escrito y puede redactar noticias deepfake o ultrafalsas. Estas, a ojos inexpertos, son prácticamente indistinguibles de las escritas por periodistas reales. La empresa ha declarado sentir tanta preocupación por el mal uso que podría hacerse de esta tecnología que está reteniendo la publicación de sus investigaciones para comprender plenamente las posibles consecuencias.

Broussard, una ingeniera informática que actualmente se dedica al periodismo de datos, se halla en la intersección entre la inteligencia artificial y la cobertura informativa. Su equipo desarrolló una herramienta IA llamada Bailiwick, que les permitió visualizar los datos de financiación de las campañas electorales estadounidenses de 2016.

Según ella, puede llevar años y muchísimo análisis de documentos completar un reportaje de investigación de gran envergadura, un proceso que puede alcanzar los millones de euros.

“Mis proyectos son de bajo coste en comparación. Eso es importante desde el punto de vista de la innovación”, afirma Broussard, aunque no cree que la IA vaya a sustituir a los periodistas. Y añade: “Hay quien dice que la tecnología es la mejor solución. Yo a eso lo llamo “tecnochovinismo”. En algunos círculos se creía que no necesitábamos tantos reporteros y que podían aprenderlo todo de las redes sociales. Se ha demostrado que no es verdad”.

Muchos ven la función de la inteligencia artificial como herramienta para asistir a los periodistas, en lugar de como sustituta de estos. Para quienes trabajan en periodismo local, un ámbito en el que los periódicos desaparecen a un ritmo sin precedentes, puede que suponga una manera de evitar su extinción.

Cuenta Toby Abel, director de tecnologías de Krzana, una empresa que se dedica a pertrechar de herramientas basadas en IA a medios de noticas locales: “Desde la irrupción de las redes sociales, el modelo publicitario no sirve de nada en el periodismo local. Vemos la oportunidad de adoptar nuevos modelos de financiación con un énfasis mucho mayor en el valor y la confianza del lector, que es quien paga ahora, en lugar del anunciante. La función de la IA es encargarse de las partes del periodismo que, en esencia, ocupan mucho tiempo de trabajo, e intentar reemplazarlas por soluciones baratas y rápidas que no estorben a los periodistas”.

Krzana —un juego de palabras en sánscrito que hace referencia a los actos de encontrar perlas y un pulso humano— es una herramienta que, según Abel, “está intentando que la gente pueda tomarle el pulso a lo que ocurre a la vez que encuentra perlas de información”.

El programa reúne el contenido transmitido por decenas de miles de fuentes —redes sociales, blogs de la policía, actas de gobiernos locales— y lo analiza con herramientas basadas en IA, en su mayoría patentadas.

“Por ejemplo, algún periodista nos dice que quiere enterarse en cuanto alguien hable de cierto tipo de delito en Birmingham —explica Abel, que no oculta su desdén hacia las iniciativas que buscan reemplazar a periodistas humanos con reporteros robots—. Para quienes lo han intentado, la consecuencia ha sido un periodismo terrible, descafeinado, de clickbait”.

Y no son solo los grandes grupos de prensa los que están utilizando Krzana.

El West Bridgford Wire es una web de noticias hiperlocales con sede en Nottingham cuya página alcanza el millón de visitas al mes. Abel explica: “Ha cuadriplicado sus lectores en los últimos doce meses gracias a que pueden sacar noticias con un solo tío que se dedica al periodismo de investigación de forma intensiva. A mí eso me parece el futuro”.

Muchos medios utilizan herramientas de agregación de contenidos como Tweetdeck, pero Pat Gamble, editor de Wire, afirma que Krzana es más inteligente: “Lo deja todo muy limpio, como por arte de magia. La mayoría de lo que sale nos sirve”.

Gamble utiliza Krzana a diario. Para él, uno de sus puntos fuertes es que las noticias aparecen según salen publicadas, en lugar de cuando pasan por Twitter, cosa que le da ventaja a la hora de reaccionar. Y, al parecer, la web no deja de añadir nuevos anunciantes, atraídos por el contenido fresco y relevante que publica.

Parte de la financiación para el uso en aumento de IA en el periodismo local y regional proviene de dos de las compañías que han contribuido en gran medida a la quiebra de las prensas informativas locales, a pesar de haber prosperado gracias al contenido que estas generan: Facebook y Google. En enero de 2017 se introdujo el Facebook Journalism Project para “establecer vínculos más fuertes entre Facebook y la industria informativa”. Sus objetivos eran desarrollar productos informativos colaborativos y ofrecer formación y herramientas tanto a periodistas como a particulares.

Desde entonces ha celebrado varios hackatones (encuentros de programadores que se reúnen para crear productos de software) a los que han acudido agencias de noticias, algunas de las cuales han visto el desarrollo de herramientas IA por parte de equipos.

El año siguiente vio el lanzamiento de Google News Initiative, que pretende “empoderar a agencias de noticias a través de la innovación tecnológica”.

Abel, de Krzana, opina: “Creo que es un peligro que [la financiación] se utilice como apoyo para permitirle al periodismo local que siga sin ganar dinero. Debería utilizarse como un trampolín. Una inyección de capital es una gran manera de resolver un problema de impulso para avanzar hacia un periodismo local sostenible”.

Un proyecto que ha recibido financiación de Google es una herramienta basada en IA llamada Inject, cuyo desarrollo ha corrido a cargo de un equipo dirigido por Neil Maiden, profesor de creatividad digital en la Cass Business School de Londres.

Como un buscador, Inject genera un índice a partir de cientos de fuentes añadidas a diario. Actualmente contiene más de 10 millones de noticias.

“Hemos escrito varios algoritmos para lo que podríamos llamar una búsqueda creativa. Google te da exactamente lo que buscas. Si buscas algo en nuestra herramienta, toma lo que escribes y busca algo parecido, pero diferente”, explica Maiden.

Inject se centra en buscar un ángulo desde el cual pueda centrarse un periodista, ya sean datos, la cara humana, una lectura larga o algo extravagante o gracioso.

Para crear los algoritmos con los que funciona Inject, el equipo de Maiden trabajó con experimentados periodistas y políticos locales para puntuar las noticias según diversos criterios y utilizar esos datos para decidir lo que hace que algo sea una “buena historia”.

“No estamos haciendo que los periodistas sean más creativos; lo que hacemos es intentar que saquen la creatividad que ya tienen, pero más rápido”, explica.

Vincent Peyregne, director ejecutivo de la Asociación Mundial de Periódicos y Editores de Noticias, cree que la IA ofrece un salvavidas a algunas personas y, a otras, una nueva manera de trabajar: “En África hay mucho interés en la IA debido a los recursos limitados con los que cuentan. La IA es una oportunidad para mejorar y crecer —afirma. Según él, el mayor reto para su adopción no es la tecnología—. Se trata de cambiar el flujo de trabajo y la cultura de tu organización. El principal obstáculo está en los puestos directivos”.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Mark Frary es periodista y escritor. Recientemente publicó De/Cipher, una guía práctica e histórica sobre la criptografía, y está trabajando en un proyecto en el que relata el ascenso de la empresa tecnológica Psion

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Dec 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 48.04 Winter 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Miriam Grace Go, Tammy Lai-ming Ho, Karoline Kan, Rob Sears, Jonathan Tel and Caroline Lees”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Winter 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the current pack of macho leaders and how their egos are destroying our freedoms. In this issue Rappler news editor Miriam Grace Go writes about how the president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, tries to position himself as the man by being as foul-mouthed as possible. Indian journalist Somak Goshal reports on how Narenda Modi presents an image of being both the guy next door, as well as a tough guy – and he’s got a large following to ensure his message gets across, come what may. The historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom considers exactly who the real Chinese leader Xi Jinping is – a man of poetry or military might? And Stefano Pozzebon talks to journalists in Brazil who are right in the firing line of Jair Bolsonaro’s vicious attacks on the media. Meanwhile Mark Frary talks about the tools that autocrats are using to crush dissent and Caroline Lees looks at the smears that are becoming commonplace as a tactic to silence journalists. Plus a very special spoof on all of this from bestselling comedic writer Rob Sears.

The Winter 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the current pack of macho leaders and how their egos are destroying our freedoms. In this issue Rappler news editor Miriam Grace Go writes about how the president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, tries to position himself as the man by being as foul-mouthed as possible. Indian journalist Somak Goshal reports on how Narenda Modi presents an image of being both the guy next door, as well as a tough guy – and he’s got a large following to ensure his message gets across, come what may. The historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom considers exactly who the real Chinese leader Xi Jinping is – a man of poetry or military might? And Stefano Pozzebon talks to journalists in Brazil who are right in the firing line of Jair Bolsonaro’s vicious attacks on the media. Meanwhile Mark Frary talks about the tools that autocrats are using to crush dissent and Caroline Lees looks at the smears that are becoming commonplace as a tactic to silence journalists. Plus a very special spoof on all of this from bestselling comedic writer Rob Sears.

In our In Focus section, we interview Jamie Barton, who headlined this year’s Last Night at the Proms, an article that fits nicely with another piece on a new orchestra in Yemen from Laura Silvia Battaglia.

In our culture section we publish a poem from Hong Kong writer Tammy Lai-ming Ho, which addresses the current protests engulfing the city, plus two short stories written exclusively for the magazine by Kaya Genç and Jonathan Tel. There’s also a graphic novel straight out of Mexico.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Will the real Xi Jinping please stand up by Jeffrey Wasserstrom: China’s most powerful leader since Mao wears many hats – some of them draconian

Challenging Orbán’s echo chamber by Viktória Serdült: Against the odds a new mayor from an opposition party has come to power in Budapest. We report on his promises to push back against Orbán

Taking on the lion by Stefano Pozzebon: With an aggressive former army captain as president, Brazilian journalists are having to employ bodyguards to keep safe. But they’re fighting back

Seven tips for crushing free speech in the 21st century by Rob Sears: Hey big guy, we know you’re the boss man, but here are some tips to really rule the roost

“Media must come together” by Rachael Jolley and Jan Fox: Interview with the New York Times’ lawyer on why the media needs to rally free speech. Plus Trump vs. former presidents, the ultimate machometer

Tools of the real technos by Mark Frary: The current autocrats have technology bent to their every whim. We’re vulnerable and exposed

Modi and his angry men by Somak Ghoshal: India’s men are responding with violence to Modi’s increasingly nationalist war cry

Global leaders smear their critics by Caroline Lees: Dissenters beware – these made-up charges are being used across borders to distract and destroy

Sexism is president’s power tool by Miriam Grace Go: Duterte is using violent language and threats against journalists, Rappler’s news editor explains

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: Putin, Trump, Bolsonaro – macho or… nacho?

Sounds against silence by Kaya Genç: Far from a bad rap here as Turkey’s leading musicians use music to criticise the government

Un-mentionables by Orna Herr: The truths these world leaders really can’t handle

Salvini exploits “lack of trust” in Italian media by Alessio Perrone: The reputation of Italian media is poor, which plays straight into the hands of the far-right politician

Macho, macho man by Neema Komba: A toxic form of masculinity has infected politics in Tanzania. Democracy is on the line

Putin’s pushbacks by Andrey Arkhangelskiy: Russians signed up for prosperity not oppression. Is Putin failing to deliver his side of the deal?[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]Trying to shut down women by Jodie Ginsberg: Women are being forced out of politics as a result of abuse. We need to rally behind them, for all our sakes[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Dirty industry, dirty tactics by Stephen Woodman: Miners in Brazil, Mexico and Peru are going to extremes to stop those who are trying to protest

Music to Yemen’s ears by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Could a new orchestra in Yemen signal the end of oppressive Houthi rule? These women hope so

Play on by Jemimah Steinfeld: The darling of the opera scene, Jamie Barton, and the woman behind a hit refugee orchestra, discuss taboo breaking on stage

The final chapter by Karoline Kan: The closing of Beijing’s iconic Bookworm has been met with cries of sadness around the world. Why?

Working it out by Steven Borowiec: An exclusive interview about workplace bullying with the Korean Air steward who was forced to kneel and apologise for not serving nuts correctly

Protest works by Rachael Jolley and Jemimah Steinfeld: Two activists on how their protest movements led to real political change in Hungary and Romania

It’s a little bit silent, this feeling inside by Silvia Nortes: Spain’s historic condemnation of suicide is contributing to a damaging culture of silence today[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Hong Kong writes by Tammy Lai-ming Ho: A Hong Kong poet talks to Index from the frontline of the protests about how her writing keeps her and others going. Also one of her poems published here

Writing to the challenge by Kaya Genç: Orna Herr speaks to the Turkish author about his new short story, written exclusively for the magazine, in which Turkish people get obsessed with raccoons

Playing the joker by Jonathan Tel: The award-winning writer tells Rachael Jolley about the power of subversive jokes. Plus an exclusive short story set in a Syrian prison

Going graphic by Andalusia Knoll Soloff and Marco Parra: Being a journalist in Mexico is often a deadly pursuit. But sometimes the horrors of this reality are only shown in cartoon for, as the journalist and illustrator show[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]Governments seek to control reports by Orna Herr: Journalists are facing threats from all angles, including new terrorist legislation[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Culture vultures by Jemimah Steinfeld: The extent of art censorship in democracies is far greaten than initially meets the eye, Index reveals[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Like brothers in arms, they revel in the same set of characteristics. They share them, and their favourite ways of using them, on social media.

Like brothers in arms, they revel in the same set of characteristics. They share them, and their favourite ways of using them, on social media.![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]