27 May 2014 | About Index, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

(Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / Demotix)

Free speech has always been a concern to the EU, with flaws in the world of press freedom and pluralism in Europe still apparent today. In an attempt to raise awareness to these problems, both on an institutional scale and publicly, DG Connect, tasked with undertaking the EU’s Digital Agenda, launched a call for proposal for funding for a new project to allow NGOs and civil society platforms to research and develop tools to tackle this problem.

The successful candidates- the International Press Institute, Index on Censorship, Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and the European University Institute in cooperation with the Central European University– will spend the next year working on the project, under the title European Centre for Press and Media Freedom.

“It is true that we regularly receive concerns about media freedom and pluralism that come from citizens, NGOs and the European Parliament,” Lorena Boix Alonso, Head of Unit for converging media and content at DG Connect told Index.

The Vice President of the European Commission, Neelie Kroes, began implementing action on this topic in 2011 with the creation of a high level group on media freedom and pluralism, but there are still violations in the world of European media freedom that need to be dealt with. These projects will be useful to raise awareness, according to Boix Alonso, to something which many people have little knowledge on.

Index on Censorship

In 2013, an Index on Censorship report showed that, despite all EU member states’ commitment to free expression, the way these common values were put into practice varied from country to country, with violations regularly occurring.

Building on this report, the DG Connect-funded project will enable Index to implement real-time mapping of violations to media freedom on a website that covers 28 EU countries and five candidate countries. Working with regional correspondents, specialist digital tools will be used to capture reports via web and mobile applications, for which workshop training will be provided. Index led events across Europe will discuss the contemporary challenges currently facing media professionals, allowing them to share good practices, while learning how to use the tools.

“Index believes that free expression is the foundation of a free society. Enabling journalists to report on matters without the threat of censorship or violations against them means promoting the right to freedom of expression and information, which is a fundamental and necessary condition for the promotion and protection of all human rights in a democratic society,” explained Melody Patry, Index on Censorship Senior Advocacy Officer.

The DG Connect grant demonstrates the current focus of the EU on the needs of journalists and citizens who face these violations to media freedom and plurality, according to Patry, as well as longer term challenges in the digital age.

Click here to visit the mediafreedom.ushahidi.com website

The Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom

For some, the need to safeguard media freedom is at the forefront of the work they do. The Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) is one such organisation and, in collaboration with the Centre for Media and Communication Studies (CMCS) at the Central European University, will continue to do so with funding from DG Connect for their project Strengthening Journalism in Europe: Tools, Networking, Training.

“The role of journalists is to both serve as guardians of government power and to enable the public to make informed decisions about key social and political issues that affect their daily lives,” the CMPF and CMCS told Index.

“The ability of journalists to freely report on issues without censorship is therefore critical- it’s the cornerstone of the checks and balances that make democracies work.”

The collaborative project will develop legal support, resources and tools for reporters, editors and media outlets to help them defend themselves in cases of legal threat, as well as raising awareness to ongoing violations to free expression and how these “impact the foundation on which democratic systems are based.” NGOs and policy makers will also benefit from this EU-funded scheme.

The International Press Institute

For over 60 years the International Press Institute (IPI) has been defending press freedom around the world, working to improve press legislation, influencing the release of imprisoned journalists and ensuring the media can carry out its work without restrictions.

London may have earned the title over recent years of libel capital of the world but what restrictions are placed on European journalists through defamation laws? This question forms the base of the IPI project, analysing existing laws and practices relating to defamation on both a civil and criminal nature; comparing this to international and European standards; and looking to the extent of which these affect the profession of journalism in all 28 EU countries and five candidate states.

After initial research, workshops will be hosted in four countries where the IPI believes they will have the greatest impact on the ground in countries where press freedom is limited by defamation to teach journalists which defamation laws affect their work, what the legitimate limits to press freedom are and what goes beyond what is internationally accepted.

According to the IPI the EU currently has no strong standards with regards to defamation and the threat to press freedom, a fact the led to their project proposal. “We hope that at one point the work we are doing will lead to a discussion within the EU about the need to develop these standards,” Barbara Trionfi, IPI Press Freedom Manager, explained to Index. “The defence of press freedom is a fight anywhere and it does not stop even in western Europe. It is still a major problem.”

Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso

“We aim at improving the working conditions of media professionals and citizen journalists in Italy, South-East Europe and Turkey and ultimately at enhancing the quality of democracy,” Francesca Vanoni, Project Manager at Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso (OBC) told Index.

OBC has been reporting on the socio-political and cultural developments of south-east Europe since 2000 and through their DG Connect funded project will monitor and document media freedom violations in nine countries, including Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Romania and Serbia.

Offering practical support to threatened journalists, the project will raise public awareness of the European dimension on media freedom and pluralism, stimulating an active role of the EU with regard to media pluralism in both member states and candidate countries. This will be implemented, among other means, through social media campaigns, a crowd-sourcing platform, an international conference for the exchange of best practices and transnational public debates.

The idea behind the project was to help build a European transnational public sphere in order to strengthen the EU itself. The ethics and professionalism of media workers is crucial, according to Vanoni. A democratic environment is built upon the contribution of all parts involved: “The protection of media freedom is fundamental for the European democracy and it cannot be left aside of the main political priorities.

“Being part of a wider political community that tackles shared problems with shared solutions offers stronger protection in case pluralism is threatened,” explained Vanoni.

To make a report, please visit http://mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

This article was published on May 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Apr 2014 | Asia and Pacific, Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, Singapore

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Speaking in a Singaporean university seminar room in early March, Lord David Puttnam highlighted the importance of media plurality. He saw it as a means to an end, a way to foster an informed citizenry in a society where no one person or entity has too much influence over the media.

It was an interesting location for him to be talking about media plurality. Thanks to the laws and regulations establish by the People’s Action Party government – the party’s rule has been uninterrupted since Singapore achieved self-governance in 1959 – the country has not had true media plurality for a long time. Most mainstream media organisations are owned by government-linked corporations, and the government also has the power to appoint management shareholders to newspaper companies.

This has resulted in a mainstream media that revolves more around educating Singaporeans along official narratives rather than serving as a Fourth Estate. But as Singaporeans increasing turn to the internet as their source of news and information, websites and blogs are making an unmistakable impact on Singapore’s media landscape.

The Online Citizen (TOC) is a notable example. Launched in 2006, the website is unabashedly political in a country where the subject of politics is often approached with trepidation. “Our specialty is in reporting on social issues and government policy. We tend to focus on cases where policy has affected people in ways that you will not see touted in mainstream media, and we try to increase our readers’ perspective on these issues, so they can think about the way forward,” the TOC core team wrote in an email to Index.

The issues that TOC has covered vary from poverty and homelessness to the exploitation of migrant workers. Commentaries have examined numerous state policies, from public housing to media regulation. It was also one of the major alternative websites that covered the 2011 general Election — the first election in which online and new media was prevalent.

Since then, several new platforms have emerged. They cover a spectrum, from New Nation‘s satirical humour to The Independent Singapore‘s attempt to bring non-mainstream professional journalism to the online sphere. This blossoming of online websites has been accompanied by parallel discussions on social media platforms, especially Facebook and Twitter. Where Singaporeans once only had establishment-dominated mainstream media voices to tune in to, alternative perspectives, criticism and discussion are now common online.

The threat the online community poses to the government’s hegemony has not gone unnoticed. Government figures have said plenty about the dangers of the internet, going so far as to label it a threat that could hamper Singapore’s Total Defence strategy. An acronym, DRUMS, was invented. It stands for Distortions, Rumours, Untruths, Misinformation and Smears.

Defamation suits and warning letters from lawyers have also been issued to various blogs and websites. The Attorney-General’s Chambers is now trying to take legal action against prominent blogger Alex Au, accusing him of having “scandalised the judiciary” – the same charge that British journalist Alan Shadrake faced in 2010.

Legislation has also been invoked to exert some control (or at least influence) over the internet. In 2011, TOC was gazetted by the prime minister’s office as a “political association”. This meant that TOC would not be able to receive any foreign funding, and that anonymous donations made to the website had to be limited to S$5,000 (£2,377) a year. Once that amount is reached, anyone who would like to donate will have to be identified.

The move has limited TOC’s ability to fund its work. “Classifying us as a political website gives potential investors the impression that TOC is aligned with partisan politics, where the truth is we do not align ourselves with any political party. Such an impression has an impact in terms of encouraging people to donate to the website,” TOC explains.

But TOC is not the only website to have felt the government’s “light touch” on the internet. In 2013 the government announced a new licensing regime: popular news websites – defined as those that receive more than 50,000 unique visitors a month – would need to get licenses from the Media Development Authority. They would be required to put down a S$50,000 (£23,772) bond and commit to taking down any material deemed in breach of content standards within 24 hours.

The regime was put in place very quickly, and ten websites were identified for licensing. Only one — Yahoo! Singapore’s news website — was not a website owned by Singapore’s mainstream media corporations and already regulated under other legislation.” The government said that blogs would not be licensed under these rules, but citizen journalists are not so sure. After all, the MDA defines “news reporting” as “any programme (whether or not the programme is presenter-based and whether or not the programme is provided by a third party) containing any news, intelligence, report of occurrence, or any matter of public interest, about any social, economic, political, cultural, artistic, sporting, scientific or any other aspect of Singapore in any language (whether paid or free and whether at regular interval or otherwise) but does not include any programme produced by or on behalf of the Government.” The definition is more than broad enough to encompass the work done by some blogs.

Outside of the licensing regime, three other alternative websites have since been singled out for registration with the MDA. Registering with the MDA requires a website to make all its editorial staff known to the regulators, as well as declare that it will not receive any foreign funding.

The Breakfast Network was asked to register late last year. It chose to shut down instead.

“We didn’t like the idea of being ‘registered’. We started as a pro bono site and some of us didn’t think it was any business of the government to have details of who was doing what,” wrote its former editor-in-chief Bertha Henson in response to Index on Censorship.

The other two websites, The Independent Singapore and Mothership.sg, decided to comply and register. They say that they have never received any foreign funding anyway, and so it’s not made too much of an impact on operations.

“I’m very open with the MDA. I tell the MDA what I do, so they don’t get overly concerned and suspicious and try to shut us down,” said Kumaran Pillai, chief editor of The Independent Singapore.

The restriction of foreign funding might cut off some funding streams for online websites, but Singapore’s blogosphere continues to grow. With the next general election (which has to be called before mid-2016) coming up, alternative websites are getting prepared. Both TOC and The Independent SG are building up to the election. But will establishment sources be willing to engage in their attempts at providing alternative coverage?

“If they won’t give us the press releases, it’s their loss,” Pillai said with a shrug. “They are going to lose out in the long run.”

This article was originally published on 23 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

8 Jan 2014 | European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

(Photo: Shutterstock)

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

“Currently the EU does not have the legal competence to act in this area [media plurality] as part of its normal business. In practice, our role involves naming and shaming countries ad hoc, as issues arise. Year after year I return to this Parliament to deal with a different, often serious, case, in a different Member State. I am quite willing to continue to exercise that political pressure on Member States that risk violating our common values. But there’s merit in a more principled way forward.”

Commission Vice President Neelie Kroes

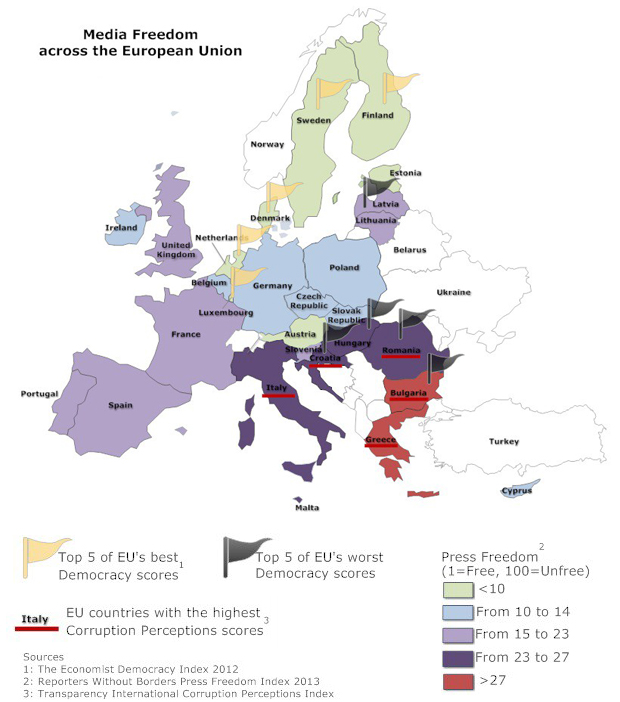

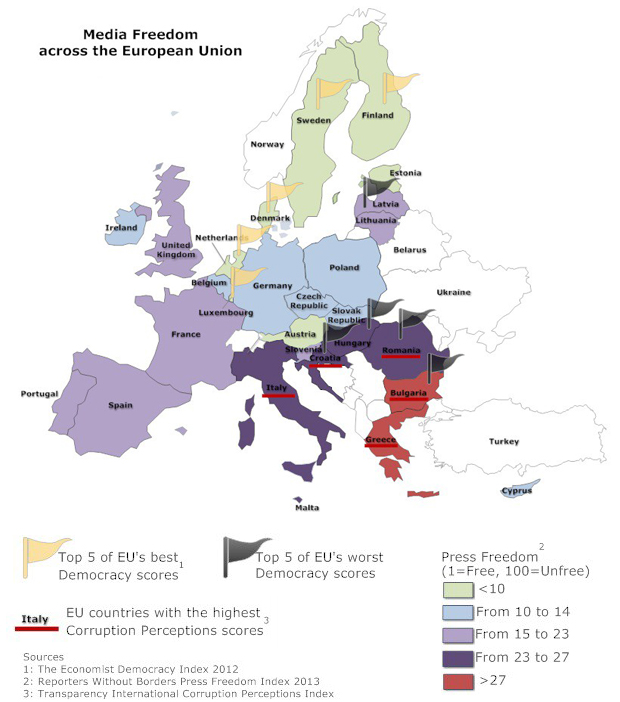

Media plurality is an essential part of guaranteeing the media is able to perform its watchdog function. Without a plurality of opinions, the analysis of political arguments in democracies can be limited.[1] Media experts argue that the European Commission has the clear competency to promote media plurality, through legal instruments such as the Lisbon Treaty and the Maastricht Treaty, but also second EU legislation. Yet, the commission has until now left the promotion of media plurality up to member states. This section will outline the ways in which some member states have failed to protect media plurality. In recent years, Italy has been the most egregious offender. Italy’s failure to protect media plurality has heightened the pressure on the European Commission to act.

The Italian “anomaly” in broadcast media included: duopoly domination in the television market, with the country’s former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi also the owning the country’s largest private television and advertising companies and a legislative vacuum that failed to prevent media concentration, as well as public officials having vested interests in the media. Legislation purportedly designed to deal with media concentration, such as the Gasperri Law of 2004, may have helped preserve them. When Mediaset owner Silvio Berlusconi became Prime Minister, he was in a powerful position, with influence over 80% of the country’s television channels through his private TV stations and considerable influence over public broadcaster RAI. This media concentration was condemned by the European Parliament on two occasions. In order to promote media plurality, in July 2010, the European Commission ruled to remove restrictions on Sky Italia that prevented the satellite broadcaster from moving into terrestrial television, in order to promote media plurality. It is possible that now the EU would have a clearer mandate to intervene using Article 11 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which came into force in 2009.[7] The Commission, however, did not intervene to prevent the conflict of interest between Premier Silvio Berlusconi, his personal media empire and the control he could exercise over the public sector broadcaster.

There are a number of EU member states where media ownership patterns have compromised plurality. A 2013 study by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom showed strong media concentrations prevalent across the EU, with the largest media groups having ownership of an overwhelming percentage of the media. These media concentrations are significantly higher than the equivalent US figures.

|

Netherlands |

UK |

France |

Italy |

| Market share for three largest newspapers |

98.2% |

70% |

70% |

45% |

|

Italy |

Germany |

UK |

France |

Spain |

Share of total advertising spend received by the two largest TV stations

|

79% |

82% |

66% |

62% |

59% |

However, the most concentrated market was the online market. The internet’s ability to facilitate the cheap open transmission of news was expected to break down old media monopolies and allow new entrants to enter the market, improving media plurality. There is some evidence to suggest this is happening: among people who read their news in print in the UK, on average read 1.26 different newspapers; those who read newspapers online read 3.46 news websites.

Yet, many have raised concerns over the convergence of newspapers, TV stations and online portals to produce increasingly larger media corporations.[2] This is echoed by the European Commission’s independent High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism. The High Level Group calls for digital intermediaries, including app stores, news aggregators, search engines and social networks, to be included in assessments of media plurality. The Reuters Institute has called for digital intermediaries to be required to “guarantee that no news content or supplier will be blocked or refused access” (unless the content is illegal).

Media plurality has not been adequately protected by some EU member states. The European Commission now has a clearer competency in this area and has acted in specific national markets. MEPs have expressed concerns over the Commission’s slow response to the crisis in Italian media plurality, a lesson that the Commission must learn from. In the future, with increasing digital and media convergence, the role of the Commission will be crucial for the protection of media plurality; otherwise this convergence could have a significant impact on freedom of expression in Europe.

[1]Index on Censorship, ‘How the European Union can protect freedom of expression’ (December 2012)

[2] p.165, Lawrence Lessig, ‘Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity” (Penguin, 2004)

27 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Since the entering into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, which made the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights legally binding, the EU has gained an important tool to deal with breaches of fundamental rights.

The Lisbon Treaty also laid the foundation for the EU as a whole to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights. Amendments to the Treaty on European Union (TEU) introduced by the Lisbon Treaty (Article 7) gave new powers to the EU to deal with state who breach fundamental rights.

The EU’s accession to the ECHR, which is likely to take place prior to the European elections in June 2014, will help reinforce the power of the ECHR within the EU and in its external policy. Commission lawyers believe that the Lisbon Treaty has made little impact, as the Commission has always been required to assess whether legislation is compatible with the ECHR (through impact assessments and the fundamental rights checklist) and because all EU member states are also signatories to the Convention.[1] Yet external legal experts believe that accession could have a real and significant impact on human rights and freedom of expression internally within the EU as the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) will be able to rule on cases and apply European Court of Human Rights jurisprudence directly. Currently, CJEU cases take approximately one year to process, whereas cases submitted to the ECHR can take up to 12 years. Therefore, it is likely that a larger number of freedom of expression cases will be heard and resolved more quickly at the CJEU, with a potential positive impact on justice and the implementation of rights in the EU.[2]

The Commission will also build upon Council of Europe standards when drafting laws and agreements that apply to the 28 member states. Now that these rights are legally binding and are subject to formal assessment, this may serve to strengthen rights within the Union.[3] For the first time, a Commissioner assumes responsibility for the promotion of fundamental rights; all members of the European Commission must pledge before the Court of Justice of the European Union that they will uphold the Charter.

The Lisbon Treaty also provides for a mechanism that allows European Union institutions to take action, whether there is a clear risk of a “serious breach” or a “serious and persistent breach”, by a member state in their respect for human rights in Article 7 of the Treaty of the European Union. This is an important step forward, which allows for the suspension of voting rights of any government representative found to be in breach of Article 7 at the Council of the European Union. The mechanism is described as a “last resort”, but does potentially provide leverage where states fail to uphold their duty to protect freedom of expression.

Yet within the EU, some remained concerned that the use of Article 7 of the Treaty, while a step forward, is limited in its effectiveness because it is only used as a last resort. Among those who argued this were Commissioner Reding, who called the mechanism the “nuclear option” during a speech addressing the “Copenhagen Dilemma” (the problem of holding states to the human rights commitments they make when they join). In March 2013, in a joint letter sent to Commission President Barroso, the foreign ministers of the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark and Germany called for the creation of a mechanism to safeguard principles such as democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The letter argued there should be an option to cut EU funding for countries that breach their human rights commitments.

It is clear that there is a fair amount of thinking going on internally within the Commission on what to do when member states fail to abide by “European values”. Commission President Barroso raised this in his State of the Union address in September 2012, explicitly calling for “a better developed set of instruments” to deal with threats to these rights.

This thinking has been triggered by recent events in Hungary and Italy, as well as the ongoing issue of corruption in Bulgaria and Romania, which points to a wider problem the EU faces through enlargement: new countries may easily fall short of both their European and international commitments.

Full report PDF: Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Footnotes

[1] Off-record interview with a European Commission lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).

[2] Interview with Prof. Andrea Biondi, King’s College London, 22 April 2013.

[3] Interview with lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).