4 Feb 2015 | Africa, mobile, News and features, Nigeria

Walls are plastered with campaign posters ahead of the 14 Feb elections in Nigeria. (Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung/Flickr)

Update: This article was posted before Nigerian election authorities postponed the polls until March 28, 2015.

As Nigeria’s 14 February general election approaches, the menace of Boko Haram has intensified. Attacks are more frequent and brutal. No Nigerian is entirely safe.

In Baga, a community in Borno state in Nigeria’s north-east, over 2000 people were reportedly killed in a single attack in January. Boko Haram is easily one of the world’s deadliest terror groups — a group that slit 61 school boys’ throats in a raid; that straps bombs on 10 year-olds; that has kept 276 school girls abducted for almost a year and is abducting more; that has killed over 30,000 Nigerians and left over 3 million displaced.

The group now controls a land mass the size of Costa Rica, collects taxes, has its own emirs and has declared a caliphate incorporating parts of Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroon. On 25 January 2014, the group, in a very daring move, made efforts to seize Maiduguri, the Borno state capital.

Boko Haram’s activities are not restricted to the north-eastern part of Nigeria as generally believed. The attacks on the UN headquarters and police headquarters in Abuja, the federal capital city, and several other deadly assaults occurred in Nigeria’s north central states.

The group’s attacks have stagnated economic growth in the north east and weakened diplomatic relations between Nigeria and neighbouring countries. In an escalation, Chadian troops have attacked Boko Haram positions in Nigeria, the BBC reported on 3 Feb.

Local views

While the group has consistently reiterated that it is out to Islamise Nigeria, a good number of Nigerians — Muslims and Christians alike — find this implausible.

Initially it was a convincing strategy because the group targeted mostly Christian places of worship and a few government institutions. Over time, however, the attacks became more random and less deliberate. Individuals of different ethnic groups and religious convictions were dragged off buses and killed in vile operations in broad daylight, typically lasting several hours with no interruption from security agencies. Entire villages have been ransacked regardless of religion or ethnicity.

Some Nigerian Christians however, opt to stick with Boko Haram’s initial script, pointing out that the group’s attacks bear a close resemblance to those of ISIS, known to have a very low tolerance for people of other faiths and liberal Muslims. A handful of northern Muslims agree with this line of thought.

There are also those who believe the group is being funded by some members of the northern Islamic political elite for selfish gain. Such theories appear to have basis in fact. At least one sitting senator and a former governor of Borno state, have been closely linked at various times to the group. Why none of them have been investigated leaves most Nigerians baffled.

There are other theories about the rise of Boko Haram that pin the blame on the government. This line of reasoning cites the president’s southern heritage for a lack of interest with the violence in the north. Southerners are seen to be taking vengeance for the loss of lives and property suffered at the hands of northerners during the Biafran War of 1967. Boko Haram also presents another route for siphoning Nigeria’s funds into private accounts.

The accusations of a self-acclaimed Australian “negotiator”, Stephen Davies, that Nigeria’s former Chief of Defence Staff, Major General Azubuike Ihejirika, a southern Christian, was actively involved in funding Boko Haram activities while working to undermine Nigeria’s army, resonated with many Nigerians of northern extraction who believe the current administration is out to cripple the region. Some southerners, on the other hand, say the northerners brought Boko Haram upon themselves and should therefore reap the fruits of their folly. Such people neither see Boko Haram as a national threat nor believe there is any truth to some of the harrowing stories coming out of the north, viewing them simply as an attempt to frustrate President Goodluck Jonathan, himself a southern Christian, out of office.

Media silence

The media in Nigeria, despite their seeming independence, are divided along political lines depending on ownership. Government media are biased in favour of the government while the private media lean towards the political loyalty of the owner. Accountability to the citizens is low.

Investigative reporting on the situation in the north by local media is limited. Local journalists are quick to point out that they lack the support of their respective organizations to report these stories. The lack of insurance, social benefits or recognition in the event of death is also cited as reasons for this reluctance. Indeed several media houses have been attacked without any response from the authorities.

Nigerians will often quote foreign press in authenticating their stories, since other local sources are generally viewed as suspect. For instance, while authorities put the deaths in Baga at 150–based primarily on guess work, foreign media reported 2,000 deaths based on satellite imagery and interviews with some who escaped the carnage.

The military appears helpless. Stories are told of soldiers who trade their arms for mufti from the locals or wear civilian clothes under their uniforms in order to enhance escape in the event of an attack. Boko Haram is considered more brutal to soldiers.

In a recent interview with CNN anonymous soldiers said that supplies and incentives are low, morale is lacking and wounded soldiers are made to pay for their treatment. A spokesperson for the military has since denied these allegations, labelling the claims “satanic”. There has been at least one incident of mutiny among the troops in the north.

Most Nigerians see BH as a threat to Nigeria’s development and would want an end to the menace. Life is now altered. Roads that were four lanes in the past are now narrowed to a lane or two in areas with a heavy government presence. The roads in the country are heavily guarded, and a general sense of unease and fear rules especially in northern Nigeria.

Will Nigerians speak to the situation in the coming presidential elections? Tough question. Ordinarily yes, Nigerians will respond by voting out a government that has shown a complete lack of determination, political will or focus to counter Boko Haram.

But this is Nigeria. The political elite have successfully used religion and ethnicity to divide the populace, wherein voting, even if it counts, will be coloured by ethnicity and religion. Even so, for the first time in the annals of Nigeria’s history, the president’s campaign convoy has been repeatedly stoned.

February 14, Valentine’s day, Nigeria’s Presidential elections day, will tell where the love truly lies.

This article was originally published on 4 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Dec 2014 | About Index, Draw the Line, Young Writers / Artists Programme

Religious freedom and religious radicalism which leads to extremism has become an increasingly difficult balancing act in the digital age where presenting religious superiority through fear and “terror” is possible both locally and internationally at internet speeds.

The ongoing series of beheading videos released by the Islamic State and the showcase of kidnapped school girls by Nigeria’s Boko Haram on YouTube are both examples that test the extent to which the UN Convention of Human Rights can protect religious freedoms. According to a report by the International Humanist and Ethical Union, Egypt’s Youth Ministry are targeting young atheists vocal on social media about the dangers of religion. In Saudi Arabia, Raef Badawi was sentenced to seven years in prison in 2013 and received 600 lashes for discussing other versions of Islam, besides Wahhabism, online.

Article 18 of the Convention states that the “right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance”. The interpretation of “practice” is a grey area – especially when the idea of violence as a form of punishment can be understood differently across various cultures. Is it right to criticise societies operating under Sharia law that include amputation as punishment, ‘hadd’ offences that include theft, and stoning for committing adultery?

Religious extremism should not only be questioned under the categories of violence or social unrest. Earlier this month, religious preservation in India has led to the banning of a Bollywood film scene deemed ‘un-Islamic’ in values. The actress in question was from Pakistan, and sentenced to 26 years in prison for acting out a marriage scene depicting the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter. In Russia, the state has banned the publication of Jehovah’s Witness material as the views are considered extremist.

In an environment where religious freedom is tested under different laws and cultures, where do you draw the line on international grounds to foster positive forms of belief?

This article was posted on 15 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

4 Sep 2014 | News and features, Nigeria, United Kingdom

Lady Apostle Helen Ukpabio was banned from travel to the UK in April 2014

Lady Apostle Helen Ukpabio is a pastor, author, film producer, actress, artist, composer and singer and founder of Liberty Foundation Gospel Ministries, based in Calabar, Nigeria. She is also, as one would suspect of someone with such a CV, possessed of admirable chutzpah.

It emerged this week that Ukpabio is threatening to sue the British Humanist Association to the tune of half a billion pounds (to be precise, £500,010,500 in costs and compensation). Ukpabio claims that the BHA, and their companions at the Witchcraft and Human Rights Information Network, have defamed her. Her specific claim against the BHA is that an article on its website claimed she believed that noisy babies may be possessed by Satan.

The article, which appeared in July 2009, says that Ukpabio wrote in her book, Unveiling The Mysteries Of Witchcraft, that “A child under two years of age that cries at night and deteriorates in health is an agent of Satan”.

In this, the article is mistaken. Ukpabio’s book does not seem to contain this sentence. Rather, under the heading “How To Recognise A Witch”, Ukpabio writes: “Under the age of two, the child screams at night, cries, is always feverish suddenly deteriorates in health, puts up an attitude of fear, and may not feed very well.”

This is not, you will see, the same. But a misquote is one thing; a libel is quite another.

The placing of this misquote at the centre of Ukpabio’s claim is based on the premise that it is fundamentally worse to accuse a child of being possessed by a devil than it is to accuse a child of being a witch, or possessed by a witch, or a vampire (as mentioned in the initial legal threat).

This is the stuff of a particularly heated thread on a Dungeons and Dragons board. It is not an argument that has a place in a chamber at the Royal Courts of Justice, in spite of that building’s Gormenghastish architecture.

That’s not the only reason the case shouldn’t come to court: the article in question was published over five years ago, apparently without ill effect on the lady Ukpabio. She admits to not having seen the article on the BHA website until earlier this year.

Her complaint, in reality, is not about the 2009 article, or the difference between satanic possession and witchcraft. Ukpabio’s underlying complaint is about a campaign to have her banned from the country in April 2014. It is the coverage of her controversial trip to Britain in April that her lawyer claims caused her to suffer reputational injury.

So why, rather than attack the numerous news outlets who reported negatively on her UK visit, during which a London venue cancelled her booking after being alerted to her witchfinding and exorcising activities, is she instead pursuing threatening humanists?

At the World Humanist Congress in Oxford last month, Nigerian delegates such as the brilliant, brave Leo Igwe, spoke passionately about preachers and witchfinders like the Lady Apostle. While in Britain “militant atheist” has become a term of abuse associated with the gauche tweets of Professor Richard Dawkins, in Nigeria, a forthright approach to religion and the abuses carried out in its name is a necessity. Humanists there are not fighting semantic battles; rather, they are engaged in a real struggle to save children and vulnerable people from accusations of witchcraft and possession: accusations that could lead to them being thrown out of their homes, beaten and even killed.

What scant support Nigerian activists receive comes from the international atheist and humanist community. While I would not cast doubt on western humanists’ solidarity with their Nigerian comrades, a costly court case would make anyone think twice before getting involved in faraway struggles again.

To grant Ukpabio’s claim any credence would be to severely inhibit the struggle against dangerous superstitions in Nigeria and elsewhere in Africa. To even get involved in an legal argument over whether satanic possession is worse than witchcraft would grant a glimmer of legitimacy to the abuse of children in the name of God. That is reason enough for the English High Court to dismiss the Lady Apostle’s ludicrous lawsuit.

This article was posted on Sept 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Jun 2014 | Cameroon, Iran, News and features, Nigeria, Russia

The 2014 World Cup in Brazil starts today, 32 nations preparing to battle it out across eight groups in the first stage of the tournament.

This year’s competition, like so many before it, comes with its designated group of death. For those not familiar with the lingo, it means the group containing the highest amount of strong teams. Or even more simply put, the group most difficult to progress from. (You can’t accuse the beautiful game of holding back on the melodrama).

Index has looked at the countries taking part in arguably the biggest show on earth, and put together our own group of death — the freedom of expression edition.

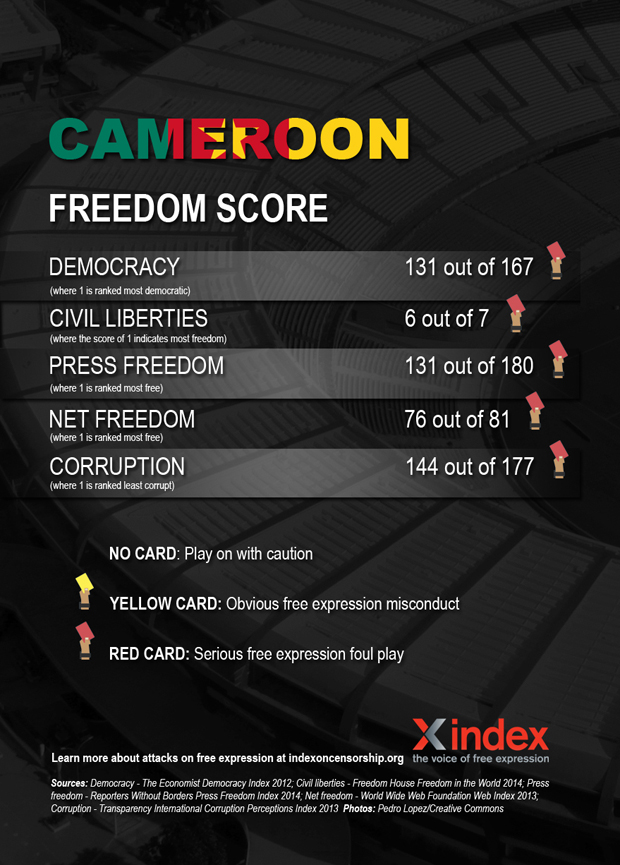

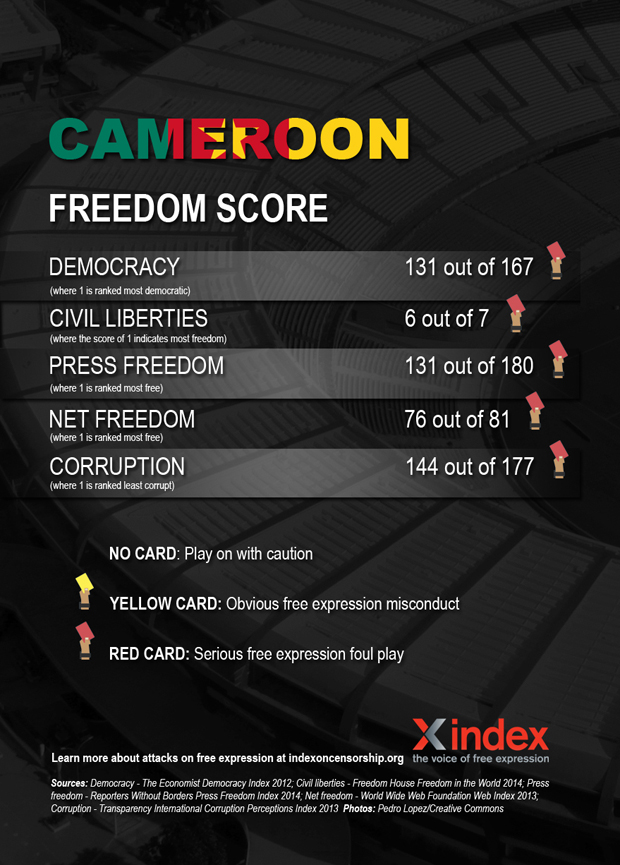

Cameroon

Cameroon — or the Indomitable Lions — have a solid track record in qualifying for the World Cup, having taken part seven time, more than any other African side. There were also the first African team to make it to the quarter final and are responsible for one of the most iconic moments in the tournament’s history. Their track record on free speech, however, is less impressive.

Freedom of expression is guaranteed in Cameroon’s constitution. Despite this, the government of Paul Biya — the country’s leader since 1982 — has been been accused numerous violations of free expression.

Large parts of the press are biased towards the ruling elite, while critical journalists face detainment, harassment and demands to reveal sources, among other things. Self censorship is widespread. In September 2013, 11 press outlets, including newspapers, radio stations and a TV station, were shut down for disrespecting “ethics and professional norms”. In 2010, former newspaper editor Germain Ngota, who had been investigating corruption allegations involving the state-run oil company, died in jail.

Freedom of assembly is often cracked down on. In 2012, former opposition presidential candidate Vincent-Sosthène Fouda and others were charged with “holding an unlawful demonstration”. The same year, security forces used tear against a crowd gathered to protest against Biya. In 2008, around 100 people were killed in clashes with police in anti-government riots.

Arts are not spared either. In 2013, Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s film Le President was banned in Cameroon because it discussed the end of Biya’s reign . In 2008, Lapiro de Mbanga, who criticised the constitutional change in term times that would allow Biya to stay in powers through song, was arrested.

Homosexuality is outlawed, and punishable by up to 14 years in prison. Human rights violations against LGBTI people, or those perceived to be, are “commonplace”. In July 2013, Eric Ohena Lembembe, director of the Cameroonian Foundation for AIDS (CAMFAIDS) was brutally murdered, in what friends suspect was an attack based on his pro-LGBTI advocacy.

Iran

Team Melli will hope that their fourth appearance at the World Cup will see them progress from the group stages for the first time. When he was elected almost a year ago, there was hope that President Hassan Rouhani would be a progressive force within Iran. The results so far have been mixed.

Since coming into power, Rouhani has taken some steps to improve press freedom, such as withdrawing 50 motions against journalists, and lifting some restrictions on previously banned topics. However, the government still controls all TV and radio, and censorship and self-censorship is widespread. The latest figures put the number of jailed journalists in Iran at 35. In January 2013, a group of journalists were arrested for allegedly cooperating with “anti revolutionary” news outlets abroad. Journalists’ associations and civil society organisations that support freedom of expression have also been targeted.

The internet and social media played a significant part in publicising and documenting the protests that followed the 2009 election, which many Iranians believed was fraudulent. The regime has banned Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and, recently, Instagram. The lead-up to the 2013 elections saw Iranian leaders tightening access to the web, and silencing “negative” news. While Rouhani — seemingly an avid Twitter user — has indicated plans to relax web censorship, the country’s plans to launch a “national internet” are said to be going ahead.

In May, eight people were jailed on charges including blasphemy, propaganda against the ruling system, spreading lies insulting the country’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Facebook. Recently, a group of young people were arrested over a video posted of them singing and dancing along to the song “Happy”, which police called was a “vulgar clip” that had “hurt public chastity”. Some commentators believe the move was meant to intimidate Iranians and discourage online criticism.

Nigeria

Brazil 2014 marks 20 years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup, and the Super Eagles arrive at the tournament as reigning Africa Cup of Nations champions. The country’s leadership, however, is not a champion of free expression.

While parts of Nigerian media is controlled by people directly involved in politics, the country can also boast a lively independent media sector. However, journalists, especially those covering sensitive topics such as corruption or separatist and communal violence still face threats. Journalists have been arrested by security forces, and media outlets have been attacked by terrorists. Legal provisions such as sedition and criminal defamation also challenge press freedom. In 2011, a journalist was arrested over stories detailing alleged corruption in the Nigerian Football Federation.

The country’s freedom of information act was put in place in 2011. However, when human rights lawyer Rommy Mom tried to use the legislation to trace some 500 million of missing aid money allocated to his flood ravaged home state of Benue, he was met with threats from people connected to the state governor, and was forced to flee.

The Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act 2013 outlawing gay marriage and relationships, was signed into law by President Goodluck Jonathan in January. The unpublished law makes it illegal for gay people to hold meetings, and outlaws the registration of homosexual clubs, organisations and associations. Those found to be participating in such acts face up to 14 years in jail.

Nigeria has come under international attention in recent months for abduction of the Chibok school girls by terrorist group Boko Haram. Among other things, Nigerians responded with the powerful #BringBackOurGirls campaign. In June however, authorities seemed to ban an offline protest against the kidnappings, before quickly backtracking. It is also worth noting that the Nigerian government has targeted journalists in their “war on terror”.

Russia

Team Sbornaya travel to Brazil in the knowledge that next time in the World Cup rolls around, they will be playing on home soil. Russia of course, recently hosted another international sporting event — the 2014 Winter Olympics. However, global attention did not improve the country’s poor record on freedom of expression. In fact, experts predicted a rise in censorship ahead of the Olympics.

Press freedom has long been under attack by Russian authorities, with TV news currently providing little beyond the official government line. In the last few months, the relatively well-respected TV channel RIA Novosti was liquidated following a decree by President Vladimir Putin, and replaced by a new press agency headed by a Kremlin-loyalist. In January, Dozhd, a popular independent TV channel was dropped by satellite and cable operators over a controversial survey. For the remaining critical journalists, Russia — one of the countries with the highest number of unpunished journalist murders — is a dangerous place to work.

The crackdown on the internet is widely believed to have started with the protests surrounding the elections securing Putin’s third term in power, organised partly through social media, but it has recently intensified. The Duma has adopted controversial amendments to an information law, targeting bloggers with blocking and fines for anything from failing to verify information posted, to using curse words. Also recently, the founder of “Russian Facebook” VKontakte says he was forced out, with the son of the head of Russia’s largest state-run media corporation predicted to take over as CEO. In 2013, the Duma approved legislation allowing immediate blocking of websites featuring content deemed “extremist”.

Public protests are discouraged through forceful responses by police, arrests, harsh fines and prison sentences. The country’s recent anti-gay legislation also pose a big threat to free expression and assembly. The ban on “promotion” of gay relationships, means that any form of expression deemed to be “gay propaganda” can be shut down. The law has also lead to physical attacks on Russia’s LGBT population.

An earlier version of this article stated that Brazil 2014 marks ten years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup. This has been corrected.

This article was published on June 12, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org