10 Sep 2015 | mobile, News and features, South Africa

Back in the days when the ruling National Party and their thought police ruled South Africa with an iron fist, one of the most powerful bodies tasked with enforcing Apartheid’s staunch Calvinistic values was the Film and Publications Board (FPB). A group of conservative, mainly Afrikaans men and women, it was their job to scrutinise and censor publications: books, movies and music.

Anything depicting even a hint of a mixing of races resulted in either an outright ban or, in the case of movies, ordered to make jarring cuts that often edited out key parts of the story. Suggestions of sex – between people of different colours – was verboten. Anything of a perceived political nature that didn’t fit in with ruling party’s narrow views was instantly banned.

The power to ban publications lay with the minister of the interior under the Publications and Entertainments Act of 1963. An entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica explains its purpose: “Under the act a publication could be banned if it was found to be ‘undesirable’ for any of many reasons, including obscenity, moral harmfulness, blasphemy, causing harm to relations between sections of the population, or being prejudicial to the safety, general.”

The result was that literally thousands of books, newspapers and other publications and movies were banned in South Africa – and possession of them was a criminal offence.

It led to some truly bizarre rulings, like the banning of Anna Sewell’s classic book Black Beauty because the censors, who clearly didn’t bother to read it, thought it was about a black woman.

I still have clear memories of returning from visits to multiracial Swaziland with banned publications hidden under carpets, slipped behind the dashboard or under spare wheels. That was how I got hold of a copy of murdered Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko’s I Write What Like and exiled South African editor Donald Woods’ Cry Freedom, about the life and death of Biko.

I still remember clearly how my heart skipped a beat when border guards checking through my car got uncomfortably close to uncovering my contraband literature. It was a huge risk because, had it been discovered, it would have meant prosecution and a criminal record for possession of banned literature.

Even having a copy of Playboy was a criminal offence and more than one South African found himself with a criminal record after a copy of the magazine was found stashed in his luggage on his return to South Africa from an overseas trip.

But when South Africa’s new, post-Apartheid constitution came into effect in 1996, it brought new freedoms for South Africans: books and movies banned by the Apartheid government were unbanned. Sex also came out into the open and, for those so inclined, pornography became freely available in the ubiquitous sex shops that opened their doors on high streets and side streets all over the country.

Then, the world wide web was in its infancy in South Africa, available only to the academics and privileged few who could afford it. But now, almost two decades later in a move that has raised fears of a new wave of censorship, the South African government last month approved a bill that has been widely criticised for seeking to curb internet freedoms. Informed by a draft policy drawn up by the FPB it seeks to amend the Film and Publications Act of 1996 – which had itself, replaced the Apartheid-era version of the Act – by adapting it for 21st century technological advances.

The amendments “provide for technological advances, especially online and social-media platforms, in order to protect children from being exposed to disturbing and harmful media content in all platforms (physical and online)”, according to a recent cabinet statement.

“The bill strengthens the duties imposed on mobile networks and internet service providers to protect the public and children during usage of their services,” it said, adding that the regulatory authority would not “issue licences or renewals without confirmation from the Film and Publication Board of full compliance with its legislation.”

The draft policy covers several areas including preventing children from viewing pornography online, hate speech and racist content.

But it also led to fear that it could be used to impose pre-publication censorship. These fears were allayed to some extent when a compromise was reached exempting content published by media registered with the Press Council of South Africa, which recently revised its press code to include regulation of online content exempted from the bill. But this is cold comfort for media who are not members, leaving them and bloggers, social media commentators and ordinary citizens vulnerable.

As it now stands anyone uploading content to the internet or posting content to social media would need to register with the FPB and submit their content before publishing anything. The proposed changes to the law would severely limit South Africa’s hard-earned, constitutional right to free speech, warn critics, who believe it would not pass constitutional muster.

This is reinforced by a legal opinion prepared for the Right to Know Campaign (R2K), which believes that the proposed bill is unconstitutional in several areas and also “unjustifiably limits the right to freedom of expression”. Opponents have made it clear that if it passes into law they will take it to the Constitutional Court.

There is no doubt that the battle lines have been drawn. Already 32,000 people opposing the bill have signed an Avaaz petition, while another 9,000 people have signed an R2K petition.

But the real issue is whether the FPB would be able to enforce it and whether trying to police the internet is just as bizarre as their predecessor’s banning of Black Beauty.

This column was posted on 10 Septemeber 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Aug 2015 | mobile, News and features, South Africa, Youth Board

This is the seventh of a series of posts written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board.

Members of the board were asked to write a blog discussing one free speech issue in their country. The resulting posts exhibit a range of challenges to freedom of expression globally, from UK crackdowns on speakers in universities, to Indian criminal defamation law, to the South African Film Board’s newly published guidelines.

Simeon Gready is a member of the Index youth advisory board. Learn more

Earlier this year, South Africa’s Film and Publication Board (FPB) released their Draft Online Regulation Policy.

The proposed regulations of this policy have huge implications for freedom of expression in South Africa, which can be summarised into the following:

• The policy claims to apply to films, games and “certain publications”. This is vague language that allows it to cover anyone publishing anything on the Internet.

• The policy allows for regulation of private personal communications.

• The policy states that anyone wishing to publish content on the internet need to apply and pay for an agreement with the FPB, meaning that individuals would be required to pay for their fundamental human right to freedom of expression.

• The policy further violates freedom of expression in that it asserts that it retains the right to take down “violent” content published by media outlets, thereby disallowing the media from being able to carry out its social responsibilities.

• The policy allows “classifiers” from the FPB to search distributor’s premises, unhindered and with no responsibility for loss or damage.

Worryingly, it has recently been announced that this policy has been approved to inform a new film and publications amendment bill. If signed into law, the repressive tactics outlined above could become a reality for South African citizens.

Simeon Gready, South Africa

Related:

• Anastasia Vladimirova: A ruthless crackdown on independent media

• Ravian Ruys: Without trust, free speech suffers

• Muira McCammon: GiTMO’s linguistic isolation

• Jade Jackman: An act against knowledge and thought

• Harsh Ghildiyal: Defamation is not a crime

• Tom Carter: No-platforming Nigel

• Matthew Brown: Spying on NGOs a step too far

• About the Index on Censorship youth advisory board

• Facebook discussion: no-platforming of speakers at universities

6 Aug 2015 | mobile, News and features, South Africa

Despite Standing Order 156 incidents of police harassment of journalists continues. (Photo: Jaxons / Shutterstock.com)

Raymond Joseph has joined Index as a columnist

Working as a reporter in the spiraling cauldron of violence in South Africa of 70s and 80s, I learned early on to be wary of the police, who would often harass, bully and even detain journalists for doing their job.

Often it happened when police, armed to the teeth, went into operational mode, firing teargas, baton rounds and even live ammunition to brutally break up protests.

While reporters were also targeted, it was photographers and cameramen who were really in the firing line. Toting cameras, they were easily visible. Their pictures or footage were regularly destroyed by police and their equipment damaged or confiscated.

As a young reporter, I became adept at stashing exposed rolls of film, slipped to me by photographer colleagues, down the front of my trousers to hide them from the police.

Anyone who worked as a journalist in those turbulent times has stories to tell of being pushed around and bullied by the police who saw the media, especially those working for the anti-apartheid era English language Press, as “the enemy”.

Fast forward two decades into post-apartheid South Africa and practically every working journalist also has a story of police harassment to tell, often arising from incidents when they were reporting or filming police officers. Many less serious incidents go unreported, accepted by journalists as part of the job.

This is happening despite the South African Police Service’s own Standing Order 156 that sets out how the police must behave towards the media. The language used is unequivocal and leaves no room for misunderstanding. It makes it clear that police cannot stop journalists from taking photos or filming, including photographing police officers. It also states that “under no circumstances” may media be “verbally or physically abused” and “under no circumstances whatsoever, may a member willfully damage the camera, film, recording or other equipment of a media representative.”

Yet despite high-level meetings between media and the police’s top brass, who say that such actions are not condoned, incidents continue to occur. The most recent meeting was in June this year between the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF) and the Johannesburg Metro Police after a photographer and TV cameraman were roughed up when they filmed officers arresting a drunk driver.

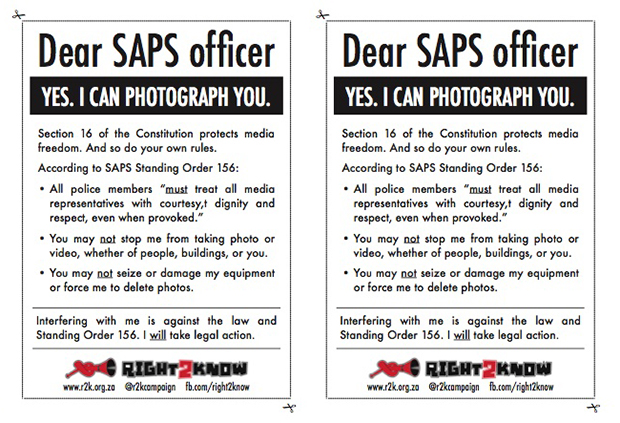

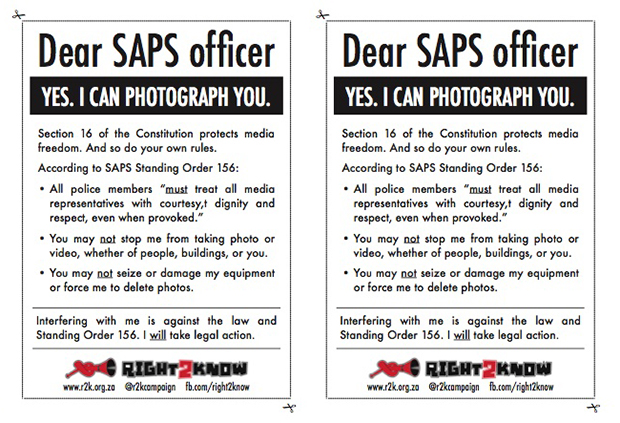

Incidents are happening so regularly that the Right2Know Campaign has published a booklet and cards explaining their rights for journalists to give to police if they are interfered with while on the job.

But, problematically, Standing Order 156 only deals with media and makes no mention of civilians who film the police using mobile phones.

“One shortcoming that we discovered in putting this together is that there isn’t enough protection for bystanders with cell phones,” says R2K spokesman Murray Hunter. “Under the Constitution, everyone has the same right to freedom of expression – working journalists and ordinary people alike. It’s especially important since bystanders with cell phones are often sources for mainstream media.

“But the direct orders that we refer to in this advisory only instruct police not to interfere with old-school media workers. So bystanders may still find themselves in a situation where the Constitution recognises their right to freedom of expression, but a police officer on the ground doesn’t.”

An example of the important role now played by citizens in newsgathering is the video footage shot by a bystander on a mobile phone of police brutalising taxi driver Mido Macia for an alleged minor parking offence. Sent anonymously to the Daily Sun newspaper, it led to the dismissal of nine policemen, who are now on trial for the killing of Macia.

One beacon of hope is that Standing Order 156 is under review after SANEF complained to the police about repeated media harassment. R2K sees this as an opportunity to include protection of the rights of citizen reporters, as well as media professionals, says Hunter.

But that could take time and involve protracted negotiations. And even if it happens there is no guarantee that police will heed the force’s own rules, or that the harassment of journalists and others will end.

It seems that the more things change, the more they will stay the same.

This column was posted on 6 August 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

21 May 2015 | Events, mobile

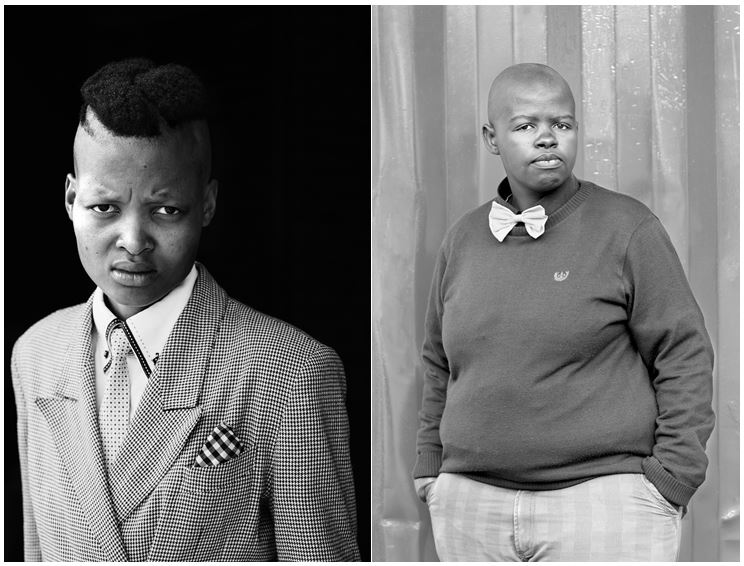

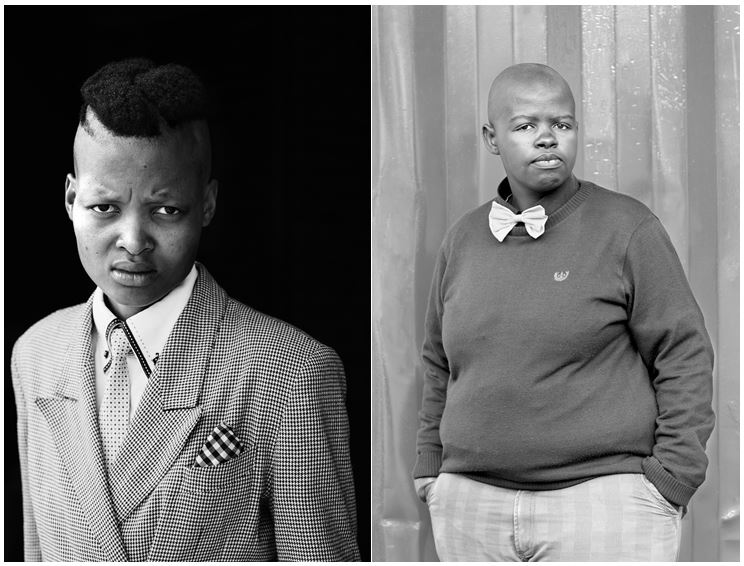

South African photographer and human rights campaigner Zanele Muholi won the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Arts Award in 2013.

Writer, campaigner and broadcaster Bidisha joins her in London to discuss the power of art in activism and the importance of visibility and representation in combating prejudice and human rights abuse.

Zanele will also be discussing her Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2015 nominated work Faces and Phases which is currently on display at The Photographers’ Gallery, London (17 Apr – 7 Jun) and at the Brooklyn Museum, New York (1 May – 1 Nov)

WHEN: Tuesday 26th May 2015, 6.30pm

WHERE: London College of Fashion, London, W1G 0BJ

TICKETS: £12 with promo code PGMEMBER (normally £20) / available here