11 Mar 2014 | Awards, News, Uganda

British theatre producer David Cecil brought worldwide attention to Uganda’s homophobic criminal code after he was arrested and charged for producing a “pro-gay” play in the country.

The Anti-Homosexuality Bill, a version of which was first introduced in 2009, was passed just before Christmas and signed by President Museveni at the end of February, meaning certain homosexual acts are now punishable with life in prison in Uganda.

The River and The Mountain tells the story of a successful young businessman who is killed by his employees after coming out as gay. Cecil was arrested in September 2012, when his theatre company refused to halt its production pending a content review by the Ugandan Media Council, and staged two performances in Kampala. The Council later deemed the play to be promoting homosexuality. Cecil spent four nights in a maximum-security prison and faced a two-year prison sentence or deportation if convicted.

The case attracted media attention both in Uganda and abroad, and Index on Censorship and David Lan, the artistic director of the Young Vic, launched a petition calling for the charges against Cecil to be dropped. It was signed by more than 2,500 people, including director Mike Leigh, Stephen Fry, Sandi Toksvig and actor Simon Callow, bringing attention to the wider issue of gay rights and freedom of expression in Uganda.

The charges were finally dropped on 2 January 2013, as the prosecution had failed to disclose any evidence. However, Cecil was re-arrested in February, spent five nights in prison, and was finally deported on the grounds that he was an “undesirable person”.

Cecil was deported from Uganda as a result of his play. He has been nominated for the Index Freedom of Expression Arts Award and spoke with Alice Kirkland about what this means to him.

Index: How does it feel to be nominated for the Index on Censorship arts award and why do you think you have been nominated?

David: The honour is bittersweet, as I am unable to continue living in Uganda because of what I did; the last year has been fraught with anxiety and uncertainty. Since meeting your representatives in early 2013, I stumbled across a load of back issues of your magazine from the 1980s. Reading through articles by Umberto Eco and Ronald Dworkin made me feel part of something bigger, a story unfolding over time.

I believe I was nominated because we were perceived as standing up for gay rights in a country where it’s hard to talk about homosexuality publicly. To me, at the time, we were just putting on a play and had little idea of how much impact it would have.

Index: You spent time in prison in Uganda for your part in the production of the “pro-gay” play The River and The Mountain. What impact has this had on your work and life since the incident? Would you or have you produced a play since on the same topic in a country that implements homophobic laws?

David: Since February 2013, I’ve been living in the UK as a deportee from Uganda, where I had spent 6 years building a career and a life with my new family (girlfriend and 2 kids, all Ugandan). With the recent (February 2014) signing of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill into law, plus other sinister developments, I now have to accept that Uganda is no longer safe for me and my family. So that chapter in my life is now closed and my family are now finally joining me here in London. This is a huge blow.

One colossal irony in all of this is that our play was not actually “pro-gay”. It simply portrayed a gay character sympathetically and satirised the politicisation of sexuality in Uganda. The people who targeted us have done all the work of promoting awareness of homosexual issues in their country.

Gay issues and rights are no obsession of mine. So, if I ever do tackle this subject again, it will be coincidental; I am primarily interested in the quality of a script or the enthusiasm of a moment.

Index: By having your production shut down, spending time in jail and facing a criminal trial you obviously had your right to free speech quashed. How did this make you feel?

David: Excited, then bemused, then frustrated, then furious, now a bit depressed – the latter mainly about Uganda, my erstwhile adopted country.

Ugandan prison was very relaxing and even pleasant. Initially, I was in the section for remand prisoners, short sentences and white-collar crime. The people were friendly, relaxed and understanding. Later, I was locked up for a week in a crowded, rough police station. That had its interesting moments, such as ghost-story-telling by candle-light, and a brilliant cast of characters. I rose to become “resident police” (prison boss) by slapping a Fagin-type with a flipflop.

My feelings are less important. I am not the victim in this story. The ones suffering are my family, and the Ugandan people.

Index: Can you explain about the run up to the production of the play in Uganda? Were you aware before the opening night that running the show could land you in jail?

David: It is important to note that the original genesis of the play comes from a meeting with a local theatre group, Rafiki. They, a group of young, heterosexual Ugandan actors and actresses, wanted to produce a play on the theme of “homosexuality”. I agreed to help, as long as it would be a comedy. Coincidentally, a friend of a friend was visiting from the UK at the time; this was Beau Hopkins, a poet and playwright, who agreed to work on the script according to a story developed in a collaborative workshop. Angella Emurwon, an award-winning Ugandan playwright, agreed to direct. It is important to note also that all the Ugandans involved are religious; one of them describes himself as a “devout Christian”.

Fast forward 4 months. I was told a week before the press premiere night that we needed to get special clearance from the Ugandan Media Council (UMC). I had already tried to secure this three months before and was told it was not necessary. (The junior UMC worker who told me this was correct; normally, one would not have to get any clearance for a theatre play in Uganda.) In the end, the secretary of the UMC decided to politicise what we were doing and, at the very last minute, insisted that I sign a letter asking us to desist until they had reviewed the script with their 11-strong committee. Pius, the secretary knew that this meant the play would not be performed, due to subsequent commitments of the director and the key actors, as I had already informed him of all that. The letter was cc-ed to the prime minister’s office, the chief of police, the head of media crimes CID and the minister of ethics & integrity. Because the letter made no mention of legal consequences, articles or anything binding, I signed.

I immediately visited a friend of mine, a human rights lawyer, Godwin Buwa, whose prognosis proved remarkably accurate in all but one regard. The letter was indeed a threat – it could not stand up in a court of law – however, one of the agencies cc-ed may try and act on it. I could be charged with something, possibly, but since the letter was so badly phrased, the worst I would suffer would be a few nights on remand. Since the case would have no water, I would be guilty of no crime and would not be deported.

We had a meeting with the cast. My name was on the paper, they were not in danger. We had worked too hard to be bullied into silence by a badly-phrased letter. We agreed to go ahead and face the consequences.

Perhaps I carried over an element of bravado from my experiences organising underground raves and music festivals in Europe, sometimes in the teeth of official sanction. At worst we had our sound system seized and threatened on numerous occasions, but always continued doing what we loved doing.

Index: Your trial brought global media attention to the situation in Uganda regarding the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, but did this attention do anything to change the laws in the country?

David: To make a faintly disgusting analogy, I think that much of the attention (from our case and others) has been like squeezing a pimple. It has brought the pus to the top.

It was never my attention to directly talk about minority rights or the laws in Uganda — I would not presume to do so. It is none of my business, in every sense. What we were trying to do was to make fun of the nonsense surrounding attitudes to gays – the very bigotry and politicisation that took us down – without getting involved in a “right or wrong” argument. Our play was funny; it was entertainment. I hope that we changed the attitudes of some audience members.

I believe communities are the source of meaning. The law either follows or clashes with that meaning. Sometimes a law may be passed to protect a minority; maybe…

The problem with international activism is that it plays right into the hands of people who argue that homosexuality is a “foreign menace”. At least, people who care about these issues should spend a significant amount of time in the countries to understand why ordinary, sound people may be homophobic. Then they can judge and engage with them.

Activism is a label with revolutionary connotations. I am certainly no activist. At most, we wanted to get people talking.

Index: What role does freedom of expression have to play in discussions about homophobia, especially in countries where it is a crime to be gay?

David: Without freedom of expression, government propaganda and lazy “common sense” prevails, especially regarding taboos or controversies. In a country where religious, ethnic and gender identities are so important and politicised, it is essential that we can discuss politics in terms of our identity, without fear of arrest.

Index: How important are awards like the Index on Censorship one in advocating free speech as a human right?

David: In Uganda, there’s a fantastic organisation called “Freethought Kampala”. They’d benefit from exposure and affiliation. I’d love to see the Index organising an event with their founder James Onen and his friends.

This article was posted on March 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Feb 2014 | Lebanon, Volume 42.04 Winter 2013

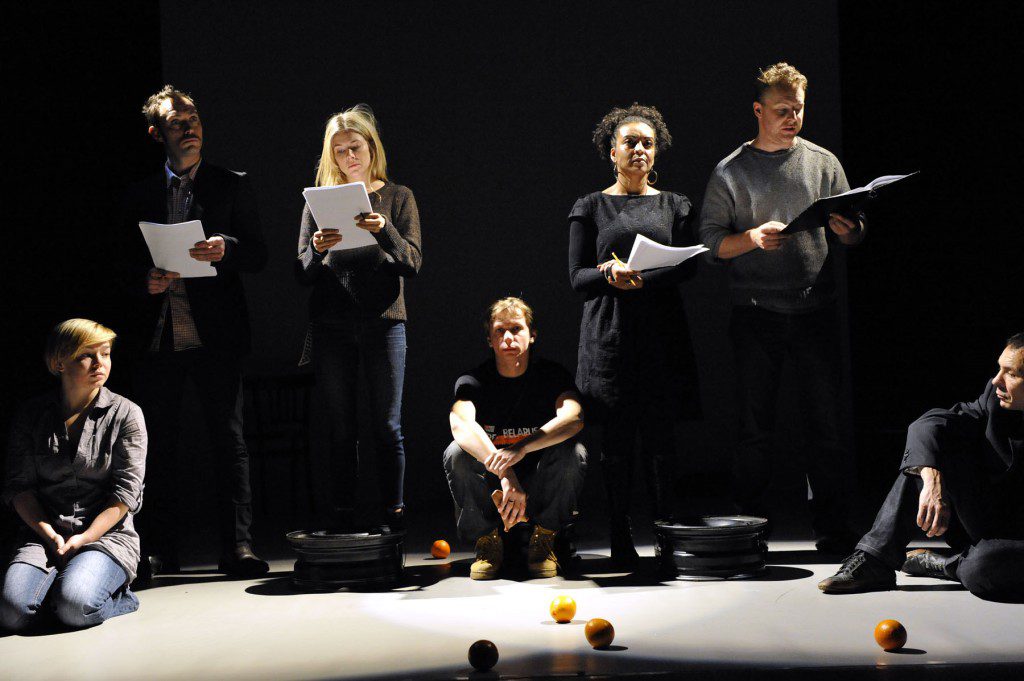

Publicity photograph for Will it Pass or Not?

(Image: http://bourjeily.com)

When writer Lucien Bourjeily made censorship the theme of his latest play, he knew he was in for a battle. And he was right. His play about censorship ended up being banned. Not surprisingly, he thinks this decision tells its own story about Lebanon today.

“Because the censorship law in Lebanon is so vague and elusive,” he says, artwork that might have received approval two years ago are “censored or banned today”. “In this climate of fear,” he adds, “the military obviously becomes more present in day-to-day life, tightening security (through countless check points in almost every corner of Lebanon) and tightening their grip on freedom of expression. For the near future, I fear that we will be hearing about more bans, more censorship, and more constraints on freedom of speech in Lebanon: censorship thrives when the state feels insecure or when it makes the common mistake of correlating security and freedom of expression.”

On 28 August, he was summoned to the Lebanese Censorship Bureau and told that his play, Will It Pass or Not?, could not go ahead. The play, which tackles the theme of censorship head on, poses the difficult question that any Lebanese artist who explores controversial or sensitive issues must consider. Prior to Bourjeily’s encounter with the interior ministry, the play was performed on university campuses to invited audiences instead of theatres. Members of the censorship board attended and broke up the performance, even though a loophole in the law meant that the play could legally be performed in the venue. So Bourjeily decided to test the board and submitted the play for their consideration. On 3 September 2013, the censorship board’s General Mounir Akiki appeared on television, presenting evidence from four so-called “critics” who insisted the play had no artistic merit and therefore would not be passed. Often, the board will recommend changes that will make an artistic work more palatable – a line removed, the omission of controversial material. But in this case, the play was simply rejected. Index decided to publish an extract of the play so readers could make their own minds up.

In this extract from Will It Pass or Not?–published for the first time in English–Lucien Bourjeily exposes the ridiculousness – and arbitrary nature – of the Lebanese Censorship Bureau, which commonly bans material that is deemed to be obscene, offensive to religions or politically sensitive. Use of this translated script is copyrighted, please contact the magazine editor at Index about use of this material

Scene 2

Sergeant Da’ja, 35, is at his desk, looking through some papers. Kareem, 27, a director, is sitting on a chair next to the desk

Kareem raises his hand.

Sergeant Da’ja How long have you been waiting?

Kareem About an hour.

Sergeant Da’ja What have you got?

Kareem A screenplay.

Sergeant Da’ja Go on then, show me.

Kareem Please, here you are.

Kareem passes Da’ja the screenplay.

Sergeant Da’ja You’ve been here before, haven’t you?

Kareem Yes, I submitted a request, but it just got sent back. Someone from your office contacted me.

Sergeant Da’ja Okay. But I can’t do anything with it. Revisions are done by Captain Shadid.

Kareem Can I see Captain Shadid?

Sergeant Da’ja When the Captain is willing to see you. You’ll have to wait.

Kareem I’ll wait.

Captain Shadid, 40, enters the room. Da’ja stands to attention.

Sergeant Da’ja Good day to you, sir.

Flustered, Da’ja shuffles his papers. Kareem raises his hand again but Da’ja ignores him. Da’ja enters the Captain’s office, stamps his foot on the ground and gives a military salute.

Captain Shadid What have we got today, then?

Sergeant Da’ja The Sun newspaper, as usual, sir.

Da’ja hands the newspaper to the captain.

Captain Shadid Madame Noha again, I suppose…

Sergeant Da’ja As usual, sir.

Captain Shadid Have you even read it, you little shit? No, no, no…Just the same old rubbish. Goodness me … What am I to do with her?

Sergeant Da’ja You know best, sir.

Captain Shadid Okay, what else have we got today? Are there many waiting out there?

Sergeant Da’ja There’s someone outside who’d like to speak to you … about his film script. It’s the tedious one about sectarianism in Lebanon and the guys who go to India and set up a secular state … and all that nonsense.

Captain Shadid Yes, yes, I remember. Show him in …

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir.

Da’ja stamps his feet and salutes, then leaves the room. Captain Shadid makes a phone call.

Captain Shadid Hi, Noha. Where are you? Come in to my office, please. I’d like a word.

Da’ja goes back to writing on his papers. Kareem raises his hand again.

Sergeant Da’ja Again? You’re an inquisitive type, aren’t you? Always asking questions… Okay, you can go in now.

Kareem enters Captain Shadid’s office. Captain Shadid is on the phone. He gestures to Kareem to give him the screenplay and then sit down.

Sergeant Da’ja Hello, sir. Er, one thing, sir. About your son?

Captain Shadid Yes, what about him?

Sergeant Da’ja There’s a match at 4pm today. Barcelona–Madrid. Who’s going to take him?

Captain Shadid Isn’t there anyone here? Isn’t Sobhi here?

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, Sobhi’s here.

Captain Shadid Well, send Sobhi then.

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir. Right you are, sir.

Captain Shadid Mr Kareem.

Kareem Yes, captain?

Captain Shadid Is this your first film?

Kareem It’s the first one I’ve decided to film, yes. It’s taken me three years to write the script.

Captain Shadid Three years and this is what you’ve got to show for yourself?

Kareem It means a lot to me. What do you mean by “this”?

Captain Shadid Listen, there’s something I want to tell you. I’m saying this to you like a brother to a brother. So, this film of yours … I’m afraid it just isn’t up to scratch. The script was 120 pages. But we’ve had to do quite a lot of work on it and it’s got a bit shorter … But it’s turned out great. Let’s take the title, to start with … I mean, how dare you use a name like that? Fucked Up until Judgment Day? Did you really think that was acceptable? Really? Where did you get that idea?

And then there’s the swearing … We counted it all up: you’ve got “fuck you” four times and “you son of a bitch” 14 times. I mean, do you really think that’s reasonable?

Kareem It’s meant to show this guy’s personality: he talks a lot of crap. It’s “dramatic tension”… it’s meant to reflect real life. People do speak like that in real life, captain.

Captain Shadid Lots of people do all kinds of things but it doesn’t mean it gets our approval, my dear man. We really couldn’t condone this character … so we’ve cut him out altogether. Dramatic tension or not: there were quite a few other things we’ve had to cut out too … Like the first scene, for example. So these guys storm out of their sectarian community and stand up to the cleric. You show the priest getting up to mischief and the sheikh taking bribes.

And these guys who just run away, off to India … We can’t have it like this. We’ve got to think of our country’s image, too. So we’ve cut out that whole scene. But don’t worry – we’ll replace it with another scene with the same ending … The guys can leave the country, that’s fine … and go to India … but for tourism instead. So we’re just changing the mood a bit. The film’s much nicer this way. Better to have a film showing a nice, pleasant world rather than this ugly nightmare you had originally. Tourists are great, so the whole idea is much nicer than the stuff with the clerics and the corruption and the bribes … And at the same time, this will encourage tourism: after all, Lebanon is a superb touristic destination.

Kareem But now the film has lost its entire meaning!

Captain Shadid What do you mean it’s lost its meaning? It’s got even more meaning now! Listen, we’re a country of diversity, of coexistence … Your film was very inflammatory. It made the country look like a well of sectarian conflict, where clerics are stirring up trouble and exploiting the country’s problems for their own political motives … No, no, no – we can’t have that.

Kareem But, sir, how can we solve our country’s problems if we don’t talk about them?

Captain Shadid Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha … Ah, so you want to solve the country’s problems now, do you? With your film? Ah, that’s wonderful … Ha, ha, ha … Listen, I’ve got to uphold the law. There are certain parameters I have to work within. And the second scene, where they arrive in India and meet the Indian cleric … well, if he’s portrayed in a negative light, then – even if he’s Indian – it reflects negatively on Lebanese clerics, too. No, no, no – we can’t allow that. Why don’t we have him meeting someone else, instead – a salesman, perhaps? Something useful like that … The Lebanese are renowned for their business acumen, after all, and this would fit with the tourism angle. We’ve killed two birds with one stone … and made it all much simpler. This way, we can approve the text … As for the third scene [he looks down at the screenplay], well … I don’t really think the film needs to be 120 pages long. So, now we’ve got it down to 20 pages. It’s great… Better than nothing, anyway, so roll with it!

Kareem But, sir, now it’s just a short film!

Captain Shadid Yes, but why not? My niece made a lovely short film and it was a big hit at all the festivals round the world. What do you have against short films?

Kareem Sir, it’s just… [Gets a bit flustered] … It’s just I … I don’t understand how you’ve got it down to 20 pages!

Captain Shadid Khalas, come now – no need to get all hot and bothered. Honestly, I get hundreds of scripts on my desk every day and I assure you, your screenplay is much better this way. It’d make a lovely short film. God grant you success!

Kareem But, Captain Shadid, I’ve spent three years working on this script! Can’t we come to a compromise? Can’t we see if there are any smaller changes we could make instead?

Captain Shadid [answering the telephone] Hello? Yes, Brigadier-General. Certainly, sir. Yes, sir. I’m looking into the matter right now, sir.

Captain Shadid gestures to Kareem to see himself out of his office.

Kareem leaves the room and sits down on a chair in Sergeant Da’ja’s office. Da’ja enters. Kareem raises his hand again.

Sergeant Da’ja What, are you still here?

Scene 5

Noha enters Captain Shadid’s office.

Captain Shadid Hi.

Noha Are you angry?

Captain Shadid Me? Why would I be angry? My wife criticises my job day in day out… and today she’s gone as far as mentioning me by name! What did you have to go and put my name in for? Why?

Noha Darling, you’re the one who’s forbidden her from putting on the play.

Captain Shadid What do you mean forbidden?

Noha Well, what else am I supposed to say?

Captain Shadid Hmmm … So … What, have you been to see this play, then?

Noha Of course. But I doubt you have?

Captain Shadid She gets naked in it!

Noha What makes you say that? Have you even seen it?

Captain Shadid No, I’ve not been to see it… But I’ve heard plenty about it from the others. What difference does it make if I’ve seen it? It contains nudity! But, anyway, nudity or not… you shouldn’t be meddling in my work!

Noha I’m just doing the same with my work as you do with yours. As a journalist, I just express my opinion about things… and then you go and meddle in my work.

Captain Shadid My job is to enforce the law.

Noha Yes, and who wrote that law?

Captain Shadid Who wrote the law? Who? The law is in the name of the Lebanese people!

Noha What, so don’t you think the Lebanese people want to go to see this play? Because there’s never an empty seat in the theatre whenever I go.

Captain Shadid Listen, I’m just doing my job… What do you want me to do? I’m your husband… So? What do you want from me? You want me to abolish censorship? Shut down the entire directorate? Sit at home and twiddle my thumbs? Give 200 soldiers the boot?

Noha Yeah, yeah, very funny.

Captain Shadid Well, it’s just not acceptable. Every day, it’s the same old story with you. Isn’t there anything else in the country you could write about besides me?

Noha I’m not the first to write about politics and have you censor it! You’re always saying, “Give it up, girl. You’re just banging your head against a brick wall.” Well, what else should I write about? First, no politics… and now art is banned as well. What should I write about, then? I may as well throw in the towel and sit at home. Is that what you’d rather? You’re always trying to censor me just like those naked women that pile up on your desk.

Captain Shadid Well, we need censorship. What would life be like without any kind of oversight? It’d be carnage… Are we back in the dark ages living in a forest? Children need oversight, society needs oversight.

Noha You said it! Children need oversight – but we’re not children! I’m not a child and I want to see the plays I want to see…Man, living in a forest in the dark ages would be better than living with you.

Captain Shadid What do you want? Shall I get your editor to censor you or shall I pull the plug on your magazine? I mean it… Do you understand?

Noha Go ahead, then, censor it. Who’s going to rush out and buy it, anyway? You guys think it’s just “oversight”… but it’s not – it’s propaganda. And forbidding things just makes them more desirable.

Captain Shadid All right, enough. But just watch it, you. I can always divorce you!

Kareem is still waiting in Sergeant’s Da’ja’s office

Sergeant Da’ja So, your name’s Dalloum? Where are you from?

Kareem The Beqaa Valley.

Sergeant Da’ja Ah, Brigadier-General Dalloum is from Beqaa. Brigadier-General Damian Dalloum.

Kareem Damian Dalloum’s a great guy.

Sergeant Da’ja You know him?

Kareem He’s my father’s cousin.

Sergeant Da’ja Wallahi, no way! His cousin? His cousin? Gosh. Wait here a minute.

Da’ja enters the Captain’s office, stamps his foot on the ground and gives a military salute.

Sergeant Da’ja Er, excuse me, sir. The chap who’s just been in to see you this morning about the Indian film … from the Dalloum family.

Captain Shadid Yes, that’s all dealt with.

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, but he’s still here waiting … We’ve just been talking and it turns out that he’s a Dalloum Dalloum … He’s related to Brigadier-General Dalloum!

Captain Shadid Damian Dalloum?

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir…

Captain Shadid Well, why didn’t he say so?

Sergeant Da’ja I don’t know, sir, I don’t think he realised.

Captain Shadid What do you mean – he didn’t realise?

Sergeant Da’ja He didn’t realise that Brigadier-General Dalloum worked here in the directorate.

Captain Shadid How could he not know?

Sergeant Da’ja He might not have known. What would you like to do, sir?

Captain Shadid This film … we’ve had a look at it, right?

Sergeant Da’ja Yes … it’s a bit disrespectful in places, with some swearing … and the title’s rather strange …

Captain Shadid The film’s fine.

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir, there’s not really much to say about it.

Captain Shadid We could perhaps just change the title.

Sergeant Da’ja But it’s fine, otherwise.

Captain Shadid Yes, yes. What are you doing waiting out there? Show him in.

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, sir.

Da’ja steps back to his own office

Sergeant Da’ja The captain would like to see you.

Kareem stands up and enters Captain Shadid’s office

Captain Shadid Come in, Dalloum. Please, sit down. This is my wife, Noha. She writes for the Sun newspaper.

Kareem A pleasure to meet you. I always read your paper.

Captain Shadid Mr Kareem, your film is wonderful.

Kareem The short or the long version?

Captain Shadid No, the long version, of course! It’s a great film, wonderful!

Kareem But weren’t there a few things …?

Captain Shadid No, no. We’ve just gone back and had another look, and you were right: there’s not really anything to worry about. It’s very realistic, after all, and it’s got just the right amount of social and political criticism.

Kareem You mean, you’ll give me permission to film it?

Captain Shadid Yes, yes, of course. Don’t you fret! [To Noha] This film gets our full approval. You see: if it’s a great work of art, we approve it, and if it’s not, we don’t. It’s simple. Why do you always have to make such a mountain out of a molehill?

Captain Shadid God bless you, Mr Kareem. Go and see Sergeant Da’ja and he’ll sign it off.

Kareem Yes, captain. Thank you very much, sir!

Sergeant Da’ja Wallahi! So the captain has given you the go ahead?

Kareem steps back into Sergeant Da’ja’s office.

Kareem Yes, er …

Sergeant Da’ja He hasn’t changed the title?

Kareem No, it’s as it was.

Sergeant Da’ja It’s a wonderful film, very deep. It made a great impression on us all. I was the one who suggested that the captain had another look. So, I’ll just sign it off, and then you come back tomorrow for the permit – if it’s not too much trouble?

Kareem Not at all. It’s no trouble.

Sergeant Da’ja And Brigadier-General Dalloum will be here tomorrow too, so you can say hello. I’ll take you to see him. So, please, mind how you go. And what else have I forgotten? Ah yes, here’s my phone number, just in case.

Kareem Your number?

Sergeant Da’ja Yes, come to me direct, if there’s anything at all you need!

Use of this translated script is copyrighted, please contact the magazine editor at Index about use of this material

Translated by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

Director and filmmaker Lucien Bourjeily brought interactive, improvised theatre to Lebanese audiences, introducing the first improvisational theatre troupe, ImproBeirut, to the Middle East in 2008. His hard-hitting play 66 Minutes in Damascus, which draws on journalists’ and activists’ descriptions of Syrian detention centres, showcased at the London International Festival of Theatre in summer 2012, receiving critical acclaim. With Kiki Bokassa, he is the co-founder of the Visual and Performing Arts Association, which advocates the use of creative arts to help resolve social issues. Bourjeily is the winner of the 2009 British Council’s Young Creative Entrepreneur Award; he won the title of best director at the 2008 Beirut International Film Festival for his debut film Taht El Aaricha; and was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship in 2010, graduating with a Master in Fine Arts in Film from Loyola Marymount University (Los Angeles). He is also the author of Index on Censorship’s Tripwires manual.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2013 print edition of Index on Censorship magazine. It was posted to indexoncensorship.org on February 12, 2014