19 Jun 2023 | News and features, United States

“In the past couple years, I’ve gotten kicked off of PayPal and Venmo,” sex worker Maya Morena told me. “I’ve gotten kicked off Twitter. I had 80,000 followers on Twitter; I had 30,000 followers on Instagram, I had 30,000 on Tumblr. I lost all those platforms.”

Morena’s experience isn’t unusual, though it also isn’t well known. When the right talks about censorship, it focuses obsessively on liberals protesting conservative speakers. When the left focuses on censorship, it points to the efforts by red states to criminalise the teaching of LGBT and Black studies. The longstanding, and worsening, policing and censorship of sex workers online is seen by all as either justifiable or unimportant. It is neither though; the censorship of sex workers affects their livelihood, their ability to advocate for themselves, and puts their safety and their very lives at risk.

That’s why when Twitter started promising that Twitter Blue would boost visibility and engagement on the platform, many sex workers signed up. The service hasn’t really solved sex worker’s problems. But the hopes around it, and the backlash to it, demonstrate just how isolated sex workers are, and how much they need solidarity from those who care about free speech.

A Sustained Assault on Sex Worker Speech

Government, gatekeepers and the public have long been very uncomfortable with sexual speech, going all the way back to laws that criminalised the shipping of sexual material through the mail in the late 1800s.

The early internet gave sex workers the ability to advertise directly to clients and to be visible online in ways that had been previously unimaginable. Sites like Backpage and Craigslist allowed people to promote erotic services and, importantly, allowed them to vet clients. Homicides of sex workers cratered in cities where Craigslist opened erotic services websites as sex workers were able to get off the streets and out of danger.

Despite clear evidence that free speech made sex workers safer, policy makers and anti-sex advocates insisted, with little to back them up, that adult services on the internet contributed to trafficking.

The “watershed moment” for sexual censorship, according to Olivia Snow, a dominatrix and a research fellow at the UCLA Center for Critical Internet Inquiry, came in 2018, with the bipartisan passage of FOSTA/SESTA. These laws made platforms legally responsible for user-generated sexual content. That gave many platforms an incentive, or an excuse, to purge sex workers.

Backpage was shut down by the government in 2018; Tumblr purged most NSFW content the same year. So did Patreon. Payment processors and banks have been escalating a longstanding war on sex workers, preventing them from accessing funds or doing business. Even OnlyFans, which has built its business almost entirely on sex workers, decided to get rid of sexual content, though it reversed its decision after a backlash from creators.

As sex workers have been shut out of most sites, Twitter has become more and more important to the community. “Twitter is the only major social media platform that tolerates us,” Snow said. “It is by default the least shitty of the platforms.”

Twitter Is Welcoming—But Not That Welcoming

A recent study found that 97% of sex workers rely on Twitter as their top site for finding followers. Writer and sex worker Jessie Sage explained that while she has accounts on sex worker sites like Eros and Tryst, “the people who book me tend to do so because they find me and then they go look at my socials.” Clients use Twitter to verify that sex workers are who they say they are, and to see if they have shared interests. And, Sage says, Twitter allows sex workers to share information. “Being able to connect with other sex workers allows us to create pathways and resources and screening resources for each other that keep us safe.”

Sage also says Twitter is vital because it lets sex workers show that they’re not just sex workers. “Most of my Twitter’s just talking about books I like to read and things that I’m thinking about,” she told me. “But there’s something very political about that, because I’m saying that I am a sex worker, and I’m also all of these other things. And when we get shoved off of social media, we lose that and we become dehumanised. And when we become dehumanised, our existence becomes much more ripe for abuse.”

While Twitter is somewhat welcoming to sex workers though, it’s not that welcoming. Sex worker accounts are often deprioritized by the algorithm (a process sometimes referred to as shadowbanning). Deprioritisation can mean that accounts don’t show up in search results or that they don’t show up in follower’s feeds. That makes it hard to build an audience. It can also make it easy for bad actors to impersonate sex workers and catfish clients. “Fake accounts on Twitter are able to get more followers than me, because I’m already censored,” Morena told me. “It’s a big problem for all sex workers.”

Twitter Blue to the Rescue, Sort Of

In December, new Twitter owner Elon Musk claimed that for $8/month, Twitter Blue users would begin to be prioritised in search and in conversations on Twitter. Many sex workers hoped Twitter Blue would give them more visibility.

Sex worker Andres Stones says that in his experience post-Musk Twitter has strangled his engagement and has “had a very large and negative impact” on his business.” It’s not clear whether this is because Musk is more aggressive in restricting adult content, or whether the new Twitter simply throttles engagement for everyone who isn’t on Twitter Blue. Either way, Stones says, “I started subscribing [to Twitter Blue] out of necessity.” It hasn’t gotten him back to where he was before, but it’s at least slowed the slide. “It’s been helpful only insofar as not having it was a death knell for engagement.”

Other sex workers report similar experiences. Morena says it hasn’t been that helpful, though it’s given her content an “extra push.” Sage struggled because Twitter Blue didn’t allow her to change her screen name easily, which made it difficult for her to advertise her travel dates.

Block the Blue

Sex workers saw Twitter Blue as a possible way to navigate censorship and deprioritisation on the one important social media platform that warily tolerates their existence. But in the broader cultural conversation, Twitter Blue was portrayed as a service solely for Elon Musk superfans and fascist trolls.

Mashable reported on a Block the Blue campaign, which encouraged Twitter users to adopt a Blocklist targeting all Twitter Blue accounts. It was embraced by NBC News reporter Ben Collins, Alejandra Caballo of the Harvard Law Cyberlaw Clinic and other large progressive accounts. Twitter comedian and celebrity @dril told Binder, “99% of twitter blue guys are dead-eyed cretins who are usually trying to sell you something stupid and expensive.” Blocking them, @dril suggested, was funny and a way to undermine Musk’s right wing political agenda.

But a small study by TechCrunch found that the vast majority of Twitter Blue accounts were not right wing harassment accounts. Instead, people used the service because they wanted features like the ability to post longer videos, or two-factor authentication—or because they were, like sex workers, businesspeople trying to boost engagement.

Ashley, a sex worker and researcher of online platform behavior who did her own study of Twitter Blue users, told me that the Block the Blue list is frustratingly counterproductive. The best way to block hateful trolls, she argued, is to block the followers of large right-wing troll accounts.

“I’m all in favour of users being empowered to block people,” she says, “but combined with the fact that so many sex workers are using this, [Block the Blue] is really just sharing a sex worker block list. Because there’s way more sex workers than hateful people on there.”

No Voice

Ashley adds that the majority of Twitter Blue users are probably just random people experimenting with the service. The point though is that sex workers are using the service at high rates, but have had little success in getting their interests, or existence, recognised by progressives who are supposedly fighting for marginalised people. Matt Binder, who wrote the Mashable article about Block the Blue, told me he doesn’t believe that sex worker concerns did much to interrupt or slow the Block the Blue campaign which has “become somewhat of a meme on the platform,” he said. (He added that he thinks more people block individual users than use the block list, and doesn’t think there’s been much “friendly fire.”)

Musk and the right are no friends to sex workers; as Snow told me, the right-wing “neo-fash, neo-Satanic Panic” targeting LGBT people is built on terror and hatred of anything associated with sexuality, which includes sex workers (many of whom are LGBT themselves.) But progressive leaders often don’t feel accountable to sex workers either, and mostly ignore sex workers when they say (for example) that blocking everyone using Twitter Blue will further isolate them.

Twitter Blue isn’t a solution. But it’s a reminder that sex workers face extreme and debilitating censorship. More people need to listen to them.

26 Mar 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Richard Littlejohn, Libby Purves, Michal Hvorecký, Karoline Kan, Andrew Morton, Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Rituparna Chatterjee and Julie Posetti”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

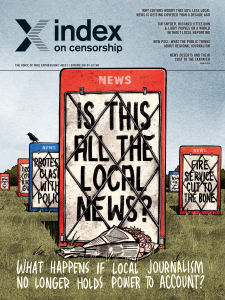

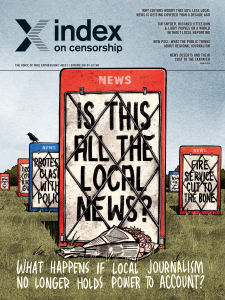

Is this all the local news? The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The spring 2019 edition of Index on Censorship looks at local news in the UK and around the world and what happens when local journalism no longer holds power to account.

Our exclusive survey of editors and journalists in the UK shows that 97% are worried that local newspapers don’t have the resources any more to hold power to account. Meanwhile the older population tell us they are worried that the public is less well informed than it used to be. Local news reporting is in trouble all over the world. In the USA Jan Fox looks at the news deserts phenomenon and what it means for a local area to lose its newspaper. Karoline Kan writes from China about how local newspapers, which used to have the freedom to cover crises and hold the government to account, are closing as they come increasingly under Communist Party scrutiny. Veteran English radio journalist Libby Purves tells editor Rachael Jolley that local newspapers in the UK used to give a voice to working-class people and that their demise may have contributed to Brexit. In India Rituparna Chatterjee finds a huge appetite for local news, but discovers, with some notable exceptions, that there is not enough investment to satisfy demand. “Fake news” is on the rise, and journalists are vulnerable to bribery. Meanwhile Mark Frary examines how artificial intelligence is being used to write news stories and asks whether this is helping or hindering journalism. Finally an extract from the dystopian Slovak novel Troll, Michal Hvorecký published in English for the first time imagines an outpouring of state-sponsored hate

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Is this all the local news?”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The future is robotic by Mark Frary Would journalists have more time to investigate news stories if robots did the easy bits?

Terrorising the truth by Stephen Woodman Journalists on the US border are too intimidated by drug cartels to report what is happening

Switched off by Irene Caselli After years as a political football, Argentinian papers are closing as people turn to the internet for news

News loses by Jan Fox Thousands of US communities have lost their daily papers. What is the cost to their area?

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson On the death of local news

What happens when our local news disappears by Tracey Bagshaw How UK local newspapers are closing and coverage of court proceedings is not happening

Who will do the difficult stories now? by Rachael Jolley British local newspaper editors fear a future where powerful figures are not held to account, plus a poll of public opinion on journalism

“People feel too small to be heard” by Rachael Jolley Columnist Libby Purves tells Index fewer working-class voices are being heard and wonders whether this contributed to Brexit

Fighting for funding by Peter Sands UK newspaper editors talk about the pressures on local newspapers in Britain today

Staying alive by Laura Silvia Battaglia Reporter Sandro Ruotolo reveals how local news reporters in southern Italy are threatened by the Mafia

Dearth of news by Karoline Kan Some local newspapers in China no longer dig into corruption or give a voice to local people as Communist Party scrutiny increases

Remote controller by Dan Nolan What happens when all major media, state and private, is controlled by Hungary’s government and all the front pages start looking the same

Rocky times by Monica O’Shea Local Australian newspapers are merging, closing and losing circulation which leaves scandals unreported

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Turning off the searchlights by Alessio Perrone The Italian government attempts to restrict coverage of the plight of refugees crossing the Mediterranean

Standing up for freedom Adam Reichardt A look at Gdańsk’s history of protest and liberalism, as the city fights back after the murder of mayor Paweł Adamowicz

After the purge by Samuel Abrahám and Miriam Sherwood This feature asks two writers about lessons for today from their Slovak families’ experiences 50 years ago

Fakebusters strike back by Raymond Joseph How to spot deep fakes, the manipulated videos that are the newest form of “fake news” to hit the internet

Cover up by Charlotte Bailey Kuwaiti writer Layla AlAmmar discusses why 4,000 books were banned in her home country and the possible fate of her first #MeToo novel

Silence speaks volumes by Neema Komba Tanzanian artists and musicians are facing government censorship in a country where 64 new restrictions have just been introduced

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

The year of the troll by Michal Hvorecký This extract from the novel Troll describes a world where the government controls the people by spewing out hate 24 hours a day

Ghost writers by Jeffrey Wasserstrom The author and China expert imagines a fictional futuristic lecture he’s going to give in 2049, the centenary of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

Protesting through poetry by Radu Vancu Verses by one of Romania’s most renowned poets draw on his experience of anti-corruption protests in Sibiu

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Press freedom: EU blind spot? By Sally Gimson Many European countries are violating freedom of the press; why is the EU not taking it more seriously?

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with editor of chinadialogue, Karoline Kan; director of the Society of Editors in the UK Ian Murray and co-founder of the Bishop’s Stortford Independent, Sinead Corr. Index youth board members Arpitha Desai and Melissa Zisingwe also talk about local journalism in India and Zimbabwe

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with editor of chinadialogue, Karoline Kan; director of the Society of Editors in the UK Ian Murray and co-founder of the Bishop’s Stortford Independent, Sinead Corr. Index youth board members Arpitha Desai and Melissa Zisingwe also talk about local journalism in India and Zimbabwe

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Dec 2018 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 47.04 Winter 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Liwaa Yazji, Karoline Kan, Jieun Baek, Neema Komba, Bhekisisa Mncube, Yuri Herrera, Peter Carey, Mark Haddon”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at why different societies stop people discussing the most significant events in life: birth, marriage and death.

In China, as Karoline Kan reports, women were forced for many years to have only one child and now they are being pushed to have two, but many don’t feel like they can talk about why they may not want to make that choice. In North Korea Jieun Baek talks to defectors about the ignorance of young men and women in a country where your body essentially belongs to the state. Meanwhile Irene Caselli describes the consequences for women in Latin America who are not taught about sex, contraception or sexually transmitted infections, and the battle between women campaigners and the forces of ultra conservatism. In the USA, Jan Fox finds Asian American women have always faced problems because sex is not talked about properly in their community. President Trump’s new “gag” law which stops women getting advice about abortion is set to make that much worse. In the far north of Scotland, controversy is raging about gay marriage. Joan McFadden finds out about attitudes to gay marriage on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland, and catches up with the Presbyterian minister who demonstrated against the first Lewis Pride. In Ghana Lewis Jennings finds there are no inhibitions when it comes to funerals. Brightly coloured coffins shaped like coke bottles and animals are all rage.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”104226″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Birth, Marriage and Death”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Labour pains by Daria Litvinova: Mothers speak out about the abuse they receive while giving birth in Russian hospitals

When two is too many by Karoline Kan: Chinese women are being encouraged to have two babies now and many are afraid to talk about why they don’t want to

Chatting about death over tea by Tracey Bagshaw: The British are getting more relaxed about talking about dying, and Stephen Woodman reports on Mexico’s Day of the Dead being used for protest

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: Taboos in the boozer. Death finds a gloomy bunch of stiffs in an English pub…

“Don’t talk about sex” by Irene Caselli: Women and girls in Latin America are being told that toothpaste can be used as a contraceptive and other lies about sex

Death goes unchallenged by Wendy Funes: Thousands of people are murdered in Honduras every year and no one is talking about it – a special investigation by Index’s 2018 journalism fellow

Reproducing silence by Jan Fox: Asian-American communities in the USA don’t discuss sex, and planned US laws will make talking about abortion and contraception more difficult

A matter of strife and death by Kaya Genç: Funeral processions in Turkey have become political gatherings where “martyrs” are celebrated and mass protests take place. Why?

Rest in peace and art by Lewis Jenning: Ghanaians are putting the fun into funerals by getting buried in artsy coffins shaped like animals and even Coke bottles

When your body belongs to the state by Jieun Baek: Girls in North Korea are told that a man’s touch can get them pregnant while those who ask about sex are considered a moral and political threat to society

Maternal film sparks row by Steven Borowiec: South Korean men are getting very angry indeed about the planned film adaption of a novel about motherhood

Taking Pride in change by Joan McFadden: Attitudes to gay marriage in Scotland’s remote islands are changing slowly, but the strict Presbyterian churches came out to demonstrate against the first Pride march in the Hebrides

Silence about C-sections by Wana Udobang: Nigeria has some of the highest infant and maternal mortality rates in the world, in part, because of taboos over Caesarean sections

We need to talk about genocide by Abigail Frymann Rouch: Rwanda, Cambodia and Germany have all dealt with past genocides differently, but the healthiest nations are those which discuss it openly

Opposites attract…trouble by Bhekisisa Mncube: Seventy years after interracial marriages were prohibited in South Africa, the author writes about what happened when he married a white woman

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]

Snowflakes and diamonds by Jodie Ginsberg: Under-18s are happy to stand up for free speech and talk to those with whom they disagree

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Killing the news by Ryan McChristal: Photographer Paul Conroy, who worked with Sunday Times correspondent Marie Colvin, says editors struggle to cover war zones now

An undelivered love letter by Jemimah Steinfeld: Kite Runner star Khalid Abdalla talks about how his film In the Last Days of the City can’t be screened in the city where it is set, Cairo

Character (f)laws by Alison Flood: Francine Prose, Melvin Burgess, Peter Carey and Mark Haddon reflect on whether they could publish their acclaimed books today

Truth or dare by Sally Gimson: An interview with Nobel prize-winning author Svetlana Alexievich about her work and how she copes with threats against her

From armed rebellion to radical radio by Stephen Woodman: Nearly 25 years after they seized power in Chiapas, Mexico, Zapatistas are running village schools and radio stations, and even putting people up for election

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Dangerous Choices by Liwaa Yazji: The Syrian writer’s new play about the horror of a mother waiting at home to be killed and then taking matters into her own hands, published for the first time

Sweat the small stuff by Neema Komba: Cakes, marriage and how one bride breaks with tradition, a new short story by a young Tanzanian flash fiction writer

Power play by Yuri Herrera: This short story by one of Mexico’s most famous contemporary authors is about the irrational exercise of power which shuts down others. Translated into English for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

Index around the world – Artists fight against censors by Lewis Jennings: Index has run a workshop on censorship of Noël Coward plays and battled the British government to give visas to our Cuban Index fellows 2018 (it took seven months)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

The new “civil service” trolls who aim to distract by Jemimah Steinfeld: The government in China are using their civil servants to act as internet trolls. It’s a hard management task generating 450 million social media posts a year

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”104225″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The winter 2018 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with Times columnist Edward Lucas, Argentina-based journalist Irene Caselli, writer Jieun Baek and law lecturer Sharon Thompson

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”104225″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The winter 2018 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with Times columnist Edward Lucas, Argentina-based journalist Irene Caselli, writer Jieun Baek and law lecturer Sharon Thompson

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

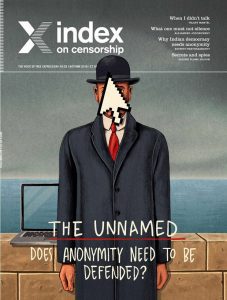

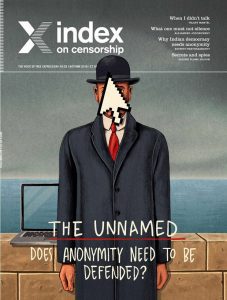

19 Sep 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Autumn 2016 magazine cover

Anonymity is out of fashion. There are plenty of critics who want it banned on social media. It’s part of a harmful armoury of abuse, they argue.

Certainly, social media use seems to be doing its best to feed this argument. There are those anonymous trolls who sent vile verbal attacks to writers such as US author Lindy West. She was confronted by someone who actually set up a fake Twitter account under the name of her dead father.

Anonymity has been used in other ways by the unscrupulous. Earlier this year, a free messaging app called Kik was the method two young men used to get in touch with a 13-year-old girl, with whom they made friends online and then invited her to meet. They were later charged with her murder. Participants who use Kik to chat do not have to register their real names or phone numbers, according to a report on the court case in the New York Times, which cited other current cases linked to Kik activity including using it to send child pornography.

So why do we need anonymity? Why does it matter? Why don’t we just ban it or make it illegal if it can be used for all these harmful purposes? Anonymity is an integral part of our freedom of expression. For many people it is a valuable way of allowing them to speak. It protects from danger, and it allows those who wouldn’t be able to speak or write to get the words out.

“If anonymity wasn’t allowed any more, then I wouldn’t use social media,” a 14-year-old told me over the kitchen table a few weeks ago. He uses forums on the website Reddit to have debates about politics and religion, where he wants to express his view “without people underestimating my age”.

Anonymity to this teenager is something that works for him; lets him operate in discussions where he wants to try out his arguments and gain experience in debates. Anonymity means no one judges who he is or his right to join in.

For others, using a fake or pen name adds a different layer of security. Writers for this magazine worry about their personal safety and sometimes ask for their names not to be carried on articles they write. In the current issue, an activist who works helping people find ways around China’s great internet wall is one of our authors who can’t divulge his name because of the work he does.

Throughout history journalists have worked with sources who want to see important information exposed, but do not want their own identity to be made public. Look at the Watergate exposé or the Boston Globe investigation into child sex abuse by priests. Anonymous sources can provide essential evidence that helps keep an investigation on track.

That right, to keep sources private, has been the source of court actions against journalists through the years. And those who choose to work with journalists, often rely on that long held practice.

Pen names, pseudonyms, fake identities have all have been used for admirable and understandable purposes over the centuries: to protect someone’s life; to blow a whistle on a crime; for a woman to get published at a period when only men did so, and on and on. Those who fought for democracy, the right to protest and other rights, often had operate under the wire, out of the searching eyes of those who sought to stop them. Thomas Paine, who wrote the famous pamphlet Common Sense “Addressed to Inhabitants of America”, advocating the independence of the 13 states from Britain, first published his words in 1776 anonymously.

From the early days of Index on Censorship, when writing was being smuggled across borders and out of authoritarian countries, the need for anonymity was paramount.

Over the years it has been argued that anonymity is a vital component in the machinery of freedom of expression. In the USA, the American Civil Liberties Union argues that anonymity is a First Amendment right, given in the Constitution. As far back as 1996, a legal case was taken in Georgia, USA, to restrict users from using pseudonyms on the internet.

Today, in India, the world’s largest democracy, there are discussions about making anonymity unlawful. Our article by lawyer and writer Suhrith Parthasarathy considers why if minister Maneka Gandhi does go ahead with plans to remove anonymity on Twitter it could have ramifications for other forms of writing. As Anja Kovacs of the Internet Democracy Project told Index, “democracy virtually demands anonymity. It’s crucial for both the protection of privacy rights and the right to freedom of expression”.

We must make sure that new systems aimed at tackling crime do not relinquish our right to anonymity. Anonymity matters, let’s remember it has a role to play.

Order your full-colour print copy of our anonymity magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Copies will be available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Carlton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

The full contents of the magazine can be read here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89160″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011400799″][vc_custom_heading text=”Going local” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011400799|||”][vc_column_text]March 2011

If the US’s internet freedom agenda is going to be effective, it must start by supporting grassroots activists on their own terms, says Ivan Sigal.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89073″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422013512242″][vc_custom_heading text=”On the ground” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013512242|||”][vc_column_text]December 2013

Attacked by the government and the populist press alike, political bloggers and Twitter users in Greece struggle to make their voices heard.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89161″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011409641″][vc_custom_heading text=”Meet the trolls” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011409641|||”][vc_column_text]June 2011

Whitney Phillips reports on a loose community of anarchic and anonymous people is testing the limits of free speech on the internet.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The unnamed” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2016 Index on Censorship magazine explores topics on anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world.

With: Valerie Plame Wilson, Ananya Azad, Hilary Mantel[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80570″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/the-unnamed/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]