18 Apr 2023 | Afghanistan, FEATURED: Francis Clarke, News

Last Thursday, human rights organisation Anotherway Now hosted a screening of the Sky News documentary ‘Defying the Taliban: women at war in Afghanistan’. This was followed by a panel discussion hosted by Index on Censorship’s Editor-at-large Martin Bright.

Part of the discussion challenged the British government to create a route for Afghan women to apply safely for asylum into the UK. Zehra Zaidi, from the advocacy group Action for Afghanistan, said people need to show they are taking up the issue with the government. She added: “We also need to show it’s not a vote loser. That it’s the right thing to do, and the compassionate thing to do. We must keep fighting.”

The first of three documentaries looking at the fight for women’s rights in the world’s most hostile environments, Special Correspondent Alex Crawford travelled to Afghanistan over a year after the Taliban takeover.

Despite being a country where women’s rights plummeted under one of the most oppressive regimes in the world, we saw young women training as gynaecologists and paediatricians, with higher-level education currently allowed for women. However, with secondary education banned for young girls and women, it’s clear this will be a rare sight in the future. With medics generally only treating their same sex in Afghanistan, a ticking time bomb awaits.

What was striking is how women operated in the underground. Crawford used her network of contacts to show us a hidden world, including a safe house in Kabul run by rights activist Mahbouba Seraj, who is a 2023 Nobel Peace Prize nominee. A rare refuge from the brutal world outside, Seraj explained she takes in abused women and girls from all over Afghanistan, adding: “The Taliban don’t want us to exist. That’s why there’s no schools or work, or why women shouldn’t be walking on the street.”

Seraj doesn’t fear the Taliban though. “I find it ridiculous, insulting and annoyingly childish. But am I scared? No”, she said.

A secret network of schools also operates across Kabul, run by volunteers who teach maths and English to a younger generation of girls.

We’re shown secret workshops where women make art out of weapons and bullets; and make beautiful dresses where they can artistically portray their tough situation. Proceeds are used to feed their families, but also gives the women the freedom to expose their treatment in a male-dominated society. However, the freedom to artistically express is no longer an option for Farida (not her real name), once one of Afghanistan’s most celebrated painters. She said: “The Taliban burnt my gallery and said you can’t work on (paint) the faces of women.

“It killed me. We are empty. Now we don’t have hopes, and we don’t have dreams.”

Postcards of artwork by Farida that was smuggled out of Afghanistan (source: Sky)

During the post-screening discussion, Crawford explained the Taliban’s hypocrisy as the official reason given for banning women from attending medical school is male/female segregation isn’t possible, but female-only medical schools are closed anyway.

Zahra Joya, an exiled Afghan journalist and founder of Rukhshana media, urged everybody to keep the conversation about Afghanistan alive after the screening. She said: “This film shows the full-scale war against women in Afghanistan. Keep them in your mind and speak up.”

Calling for a show of hands from the audience, Zaidi asked the audience if anybody knew there is currently no asylum route into the UK for Afghan women. “There is none!”, she exclaimed. “None of those women in the film can apply to the British government for asylum. Our petition alone in August had 470,000 signatures to prioritise Afghan women and girls.”

Zaidi believed the Afghanistan crisis is being purposely mixed up with the small boats’ crisis and “illegal” migration bill, so it won’t stand on its own as a genuine issue in the UK. To wrap up, she offered her dream encounter with the British home secretary.

“I like a challenge. I see myself sitting opposite Suella Braverman inviting Afghan refugees to the UK if it’s the last thing I do!”

14 Apr 2023 | Ireland, Northern Ireland, Opinion, Ruth's blog, United Kingdom

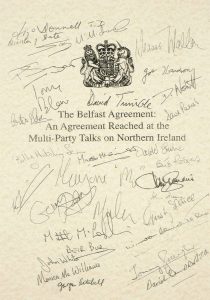

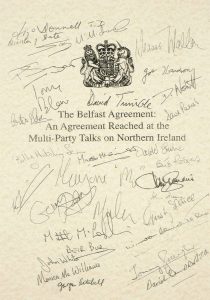

A copy of the Belfast Agreement signed by the main parties involved and organised by journalist Justine McCarthy of the Irish Independent newspaper. Photo: Whyte’s Auctions

Every day the professional staff at Index meet to discuss what’s going on in the world and the issues that we need to address. Where has been the latest crisis? What do we need to be aware of in a specific country? Where are elections imminent? Do we have a source or a journalist in country and, if not, who do we know? During these meetings we are confronted with some of the worst heartbreak happening in the world. Journalists being murdered, dissidents arrested, activists threatened and beaten, academics intimidated and while we know that we are helping them by providing a platform to tell their stories it can be soul destroying to be confronted by the actions of tyrants and dictators every day.

Which is why grabbing hold of good news stories helps keep us on track. The moments when we’ve helped dissidents get to safety, when a tyrant loses, when an artist or writer or academic manages to get their work to us. These are good days and should be cherished for what they are – because candidly they are far too rare.

It’s in this spirit that I’ve absorbed every news article, reflection and op-ed column discussing events in Northern Ireland 25 years ago. I was born in 1979, my family lived in London – the Troubles were a normal part of the news. As I grew up, the sectarian war in Northern Ireland seemed intractable, peace a dream that was impossible to achieve. But through the power of politics, of words, of negotiation, peace was delivered not just for the people of Northern Ireland but for everyone affected by the Troubles. That isn’t to say it was easy, or straightforward and that it doesn’t remain fragile, but it has proven to be miraculous and is something that we should both celebrate and cherish.

The Good Friday Agreement delivered the opportunity of hope for the people of Northern Ireland. It gave us a pathway to build trust between communities and allowed, for the first time in generations, people to think about a different kind of future. For someone who firmly believes in the power of language, who values the world of diplomacy and fights every day for the protection of our core human rights there is no single moment in British history which embodies those values more than what happened on 10 April 1998.

We can only but hope that other seemingly intractable disputes continue to see what happened in Belfast on that fateful day as inspiration to challenge their own status quo.

31 Mar 2023 | FEATURED: Mark Frary, News, Saudi Arabia

Salma is one of many Saudi prisoners of conscience to go on hunger strike

Salma al-Shehab, a 34-year-old mother of two and former PhD student at the University of Leeds, who in 2021 was handed a 34-year-long jail sentence for tweeting her support for women’s human rights defenders in her native Saudi Arabia, has gone on hunger strike.

Salma was arrested in January 2021 while on a visit home from the UK to see her family. She then faced months of interrogation over her activity on Twitter.

In March 2022 she was sentenced to six years in prison by the country’s Specialized Criminal Court (SCC) under the vague wording of the country’s Counter-Terrorism Law, but this was increased on appeal to an unprecedented 34-year term followed by a 34-year travel ban.

The SCC was originally established to try terrorism cases but its remit has widened to cover people who speak out against human rights violations in the country. Salma is one of a number of people tried by the SCC who have been handed farcically long sentences for simply expressing their human rights. The SCC is the main tool with which Saudi Arabia has effectively criminalised freedom of expression.

In January this year, Salma’s sentence was reduced to 27 years after a retrial was ordered. During the retrial, the presiding judge denied Salma the right to speak in her defence.

Salma has been joined on hunger strike by seven other prisoners of conscience, who have been handed jail terms longer than those which would be handed out to hijackers threatening to bomb a plane.

In Saudi Arabia, prisoners of conscience often go on hunger strike to protest their treatment. Those resorting to this include women’s rights activist Loujain Al-Hathloul, the blogger Raif Badawi, the academic and human rights defender Mohammad al-Qahtani, the writer Muhammad al-Hudayf and the lawyer Walid Abu al-Khair.

ALQST’s head of monitoring and advocacy, Lina Alhathloul, the sister of Loujain, said: “Knowing how harshly the Saudi authorities respond to hunger strikes, these women are taking an incredibly brave stand against the multiple injustices they have faced. When your only way of protesting is to risk your life by refusing to eat, one can only imagine the inhumane conditions al-Shehab and the others are having to endure in their cells.”

ALQST says that in previous hunger strikes, prison officials often wait several days before taking any action. “When they have eventually acted, it has been to threaten the prisoners with punishment if they continue their strike, and then place them in solitary confinement in dire conditions, subjecting them to invasive medical examinations and threatening to force-feed them. Phone calls, visitors and activities are also denied, in an attempt to coerce prisoners to end their hunger strikes,” the organisation said.

Salma and her fellow hunger strikers should never have been arrested and jailed in the first place for simply exercising freedom of expression that people take for granted in countries other than Saudi Arabia. They should have their sentences quashed and released from prison immediately.

17 Mar 2023 | News, Rwanda, Statements, United Kingdom

Home Secretary Suella Braverman will be accompanied by journalists from GB News, the Daily Mail and Daily Telegraph. Photo: UK Home Office

For the second time in twelve months, Index on Censorship has submitted a Council of Europe alert related to the exclusion of media outlets from official UK Government visits.

On 17 March, the UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman MP is due to travel to Rwanda to reaffirm the UK Government’s commitment to its controversial plan to send refugees, asylum seekers and migrants to the African country as part of the UK Government’s pledge to reduce illegal immigration.

During the trip, the Home Secretary is to meet with representatives of the Rwandan Government and visit facilities set up as part of the Migration and Economic Development Partnership, which forms part of the new Illegal Migration Bill, which is currently making its way through UK Parliament. However, as reported by The Independent, she will only be accompanied by representatives from outlets including GB News, the Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph. The BBC, The Independent, The Guardian, Daily Mirror and i newspaper have not been invited.

Martin Bright, Index on Censorship’s Editor at Large said: “We are concerned to hear that journalists from organisations judged to be critical of the government’s immigration policy have not been invited to accompany the Home Secretary on her trip to Rwanda. Democracy depends on an open and transparent relationship between government and the media, where all journalists are able to scrutinise the government. Index on Censorship believes that access to Government ministers, both domestically and as part of international visits, should not be treated as a reward for favourable coverage.”

In May 2022, Index on Censorship submitted an alert to the Council of Europe Platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists when Braverman’s predecessor, Priti Patel excluded a number of media outlets from an April 2022 trip where she signed the original deal in Kigali. At the time, the Home Office denied excluding certain journalists in an effort to avoid scrutiny. A Home Office spokesperson told the Press Gazette: “The Home Office fully adheres to the Government Communication Service Propriety Guidance when dealing with members of the media”. A spokesperson for The Guardian said: “We are concerned that Home Office officials are deliberately excluding specific journalists from key briefings and engagements”.

All alerts posted to the platform are submitted to the relevant Council of Europe member state for response. While the original alert was published on 9 May 2022, there has been no state reply as of 17 March 2023. According to the Council of Europe’s own analysis, in 2022, the UK had a reply rate of 18%.

At the time of publication, the Home Office has not commented on the exclusion of media outlets ahead of Suella Braverman’s official visit.