25 Apr 2017 | Academic Freedom, Hungary, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As a new law passed by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán’s government threatens the existence of Central European University in Budapest, 70,000 people marched in protest in the capital to save it as part of the #IStandWithCEU campaign.

Among those offering supportto protect the academic freedom of one of central Europe’s most prominent graduate universities, either by writing letters or demonstrating, include more than 20 Nobel Laureates including Mario Vargas Llosa, hundreds of academics worldwide, the European Commission, the UN, the governments of France and Germany, 11 US Senators, Noam Chomsky and Kofi Annan.

Whilst the amendment, which will effectively force CEU to shut, has been signed into statute by Hungarian president Janos Ader, the university hopes to challenge the law in the Hungary’s Constitutional Court.

In a video released on 20 April, Michael Ignatieff, president and rector of CEU, said: “Three weeks ago this university was attacked by a government who tabled legislation that would effectively shut us down. We fought back and the reception around the world has been just magnificent.”

He added: “Academic freedom is one of the values we just can’t compromise.”

Orsolya Lehotai, a masters student at CEU and one of the organisers of the street protest movement Freedom for Education, told Index that initially the small group of students had hoped to “mimic democratic society” and stop the law passing in its original form.

“So far in the seven years of the Orbán government, whenever there was big opposition to something, people have taken to the streets and this has actually changed legislation, so we decided it would show a little power if we were to have people in the streets about this,” Lehotai said. “Back then [at the first protest] we were unsure when the parliamentary debate was to happen but we had had news that it was to happen on a fast-track, which to us was outrageous.”

Despite the protests and international criticism, the Hungarian government said that the law is designed to correct “irregularities” in the way some foreign institutions run campuses. Government officials maintain that the legislation is not politically motivated.

Áron Tábor is a Fulbright scholar and another CEU student who has taken to the streets. He spoke to Index about the absurdity of the Hungarian government’s stance: “This is one university, where the language is instruction is English and the programs run according to the American system.The government says that CEU is a ‘phantom university’, or even a ‘mailbox university’, which doesn’t do any real teaching, but only issues American degrees from a distance. This is a ridiculous claim.”

Gergő Brückner, a journalist at Index.hu described the political paranoia that lies behind the new laws: “One important thing to know is that Fidesz doesn’t like anything that is not part of their own Fidesz system. You can be a famous filmmaker, a university researcher or an Olympic medal winner but you must, for them, be the part of the national circle of Fidesz.”

“If you are an independent and well-funded American university – then you are not controlled, and you can easily be portrayed as a kind of enemy,” he added.

Since its establishment in 1991, CEU has made no secret of its commitment to freedom of expression. It was founded by a group of intellectuals including George Soros, who has been much criticised by Orbán.

The university was designed to reinforce democratic ideals in an area of the world just emerging from communist control. This ethos continues: in February the annual president’s lecture at CEU was given by the University of Oxford academic Timothy Garton Ash who spoke on the topic of “Free Speech and the Defense of an Open Society”.

When the law comes into force, requirements for foreign higher education institutions to have a campus in their home country mean that it will be impossible for CEU to continue operating.

Similarly, requiring a bilateral agreement between the government of the country involved, and the Hungarian government is a huge obstacle, as in CEU’s case this would be the USA but the US federal government has made it clear that it is not within their competence to negotiate this.

More generally, the ability of the Hungarian government to block any agreement raises worrying possibilities, too. Professor Jan Kubik told Index: “A democratic government has no business in the area of education, particularly higher education, except for providing funds for it. When a government tries to play an arbiter, dictating who does and who does not have the right to teach that is a sure sign of authoritarian tendency.”

Kubik, director of University College London’s School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies, along with over a thousand other international academics, has strongly criticised the new legislation, and his department is holding a rally in London on April 26.

He has also signed an open letter published in the Financial Times.

He said: “Any governmental attempt to close down a university is always very troubling. An attack on a university in a country that has already been travelling on a path towards de-democratisation for a while is alarming.

“Universities are like canaries of freedom and independence of the public sphere. Their death or weakening signals trouble for this sphere, a sphere that is indispensable for democracy.”

With the international condemnation of the Lex CEU amendment and a likely protracted legal battle ahead, what Kubik called “a magnificent institution of higher learning, as devoted to the freedom of intellectual inquiry and high ethical standards as any of the best universities in the world” is not expected to shut its doors this year.

Meanwhile, those fighting for fundamental freedoms in Hungary will continue to challenge Orbán. European Commission vice president Frans Timmermans said, CEU has been a “pearl in the crown” of central Europe that he would “continue to fight for”, and for as long as global opinion remains so loudly behind CEU, Orbán will find it an institution difficult to silence. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493126838618-e2c5cf5d-d00a-0″ taxonomies=”2942″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Jan 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

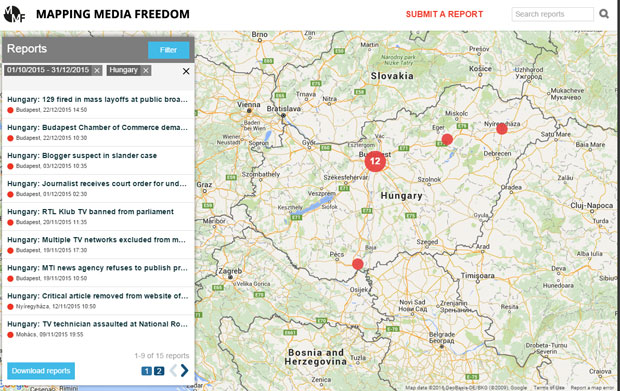

Hungary’s media outlets are coming under increasing pressure from lawsuits, restrictions on what they can publish and high fees for freedom of information requests, according to a survey of the 15 verified reports to Index on Censorship’s media monitoring project during the fourth quarter of 2015.

The Mapping Media Freedom project, which identifies threats, violations and limitations faced by members of the press throughout the European Union, candidate states and neighbouring countries, has recorded 129 verified incidents in Hungary since May 2014. In the fourth quarter of 2015 the country had the second-highest total of verified reports among EU member states and the sixth highest total among the 38 countries monitored by Mapping Media Freedom.

In 2015, Hungary was ranked #65 (partially free) on the World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders. Only two EU member states, Greece and Bulgaria received a worse score.

In autumn 2015, the law governing freedom of information (FOI) was amended after a series of investigative reports uncovered wasteful government spending through FOI requests. Under the changes, the Hungarian government was granted sweeping new powers to withhold information and allowed the government and other public authorities to charge a fee for the “labour costs” associated with FOI queries. Critics warned that fees would prevent public interest journalism, and, in at least one case, it appears they were right.

In other cases, journalists have been sued for slander and issued court orders for undercover reporting on the refugee crisis.

Here are the 15 reports with links to more information.

- 22 December 2015: Budapest Chamber of Commerce demands high price to answer FOI request

The Budapest Chamber of Commerce (BCCI) asked for 3-5 million HUF ($10,356-16,352) to answer a freedom of information (FOI) request submitted by channel RTL Klub. The Budapest Chamber of Commerce and Industry said that the price will cover the salaries of 2-3 employees who would be given the task to respond to the FOI regarding BCCI’s spending and finances.

- 22 December 2015: 129 fired in mass layoffs at public broadcaster

Even the jobs of those who work for the government-friendly state broadcaster are far from being secure. On 22 December 2015, 129 employees were laid off by the umbrella company for public service broadcasters (MTVA) in pursuit of “operational rationalisation”.

Those fired included journalists, editors and foreign correspondents. According to the MTVA, the reason for the dismissal was the “better exploitation of synergies”, “increase of efficiency” and “cost reduction”.

- 3 December 2015: Blogger suspect in slander case

András Jámbor, a blogger is suspect in a slander case because he refuted the claims of Máté Kocsis, the mayor of Józsefváros (8th district of Budapest). In August 2015, Mayor Kocsis published a Facebook post alleging that the refugees have been making fires, littering, going on rampage, stealing and stabbing people in parks.

In response, Jámbor wrote a post for Kettős Mérce blog, disproving the mayor’s claims. He added that “Máté Kocsis is guilty of instigation and scare-mongering”. The mayor denounced him for slander.

On 3 December 2015, Jámbor confirmed to police that he is the author of the blog post and sustains the affirmations he made. The police took fingerprints and mugshots of the journalist.

- 1 December 2015: Journalist receives court order for undercover report on refugee camps

Gergely Nyilas, a journalist working for Hungarian online daily Index.hu, was summoned to court for his undercover report on refugee camp conditions published in August 2015.

The journalist reentered Hungary’s borders with a group of asylum seekers and, upon being detained, told the border guards that he was from Kyrgyzstan. Dressed in disguise, Nyilas reported on his treatment by border guards, the conditions at the Röszke camp, a bus ride and his experience at the police station in Győr. He eventually admitted he was Hungarian, at which point the police let him go, the Budapest Beacon reported.

Based on a police investigation, prosecutors first charged Nyilas with lying to law enforcement officials and forging official documents. The charges were then dropped but prosecutors still issued a legal reprimand against the journalist.

- 20 November 2015: Parliament speaker bans RTL Klub TV

On 20 November 2015, László Kövér, the speaker of the parliament has banned RTL Klub television from entering the parliament building, saying that the crew broke parliament rules on press coverage. According to Kövér, the journalists were filming in a corridor, where filming was forbidden, and then refused to leave the premises after they were repeatedly asked to.

The day before, on 19 November, RTL Klub was not allowed to participate at a press conference held by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and NATO secretary general Jens Soltenberg in parliament.

RTL Klub, along with other Hungarian media outlets such as 444.hu or hvg.hu, were not invited to the press conference, but RTL Klub journalists still showed up. They attempted to enter the room with the camera rolling but were denied access. This incident reportedly led to the ban on their access.

- 19 November 2015: Multiple TV networks excluded from major press conference

RTL Klub TV, 444.hu and hvg.hu journalists were not invited to a joint press conference held in parliament by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and NATO secretary general Jens Soltenberg.

RTL Klub journalists still attempted to attend by entering the room with a camera already rolling but were still barred from entering.

They were told that the meeting was “private”, and journalists were not allowed to ask questions. Bertalan Havasi, the press secretary for the Hungarian prime minister, told them that their pass was only for the plenary session and that they must leave. However, state media outlets like M1 were allowed live transmission of the press conference, and MTI, the Hungarian wire service also published a piece about the meeting.

- 19 November 2015: MTI news agency refuses to publish press release

Publicly funded news agency MTI refused to publish a press release by Hungarian Socialist Party vice president Zoltán Lukács, where he asked for a wealth gain investigation into István Tiborcz, the son-in-law of the Hungarian prime minister. MTI refused to publish the press release, claiming that István Tiborcz is not a public figure.

The business interests of the son-in-law of Prime Minister Victor Orbán are widely discussed in the Hungarian media, especially because companies connected to Tiborcz are frequently winning public procurement tenders.

- 12 November 2015: Critical article removed from website of local newspaper

An article about a photo manipulation of Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán was removed from the website of Szabolcs Online.

The article titled, A Mass of People Saluted Viktor Orbán at Nyíregyháza – Or Not?, had a photo showing that only two dozen people gathered around the Hungarian prime minister visiting the city of Nyíregyháza. Soon after the piece was published, it was removed from the szon.hu website. However, it was reportedly still available temporarily in Google cache.

The article was a reaction to a photo published by the state news agency, MTI, that was shot in such a way that it leaves the impression that there was a big crowd around the prime minister.

- 9 November 2015: TV technician assaulted at National Roma Council meeting

A technician working for Hír TV news television was assaulted at a meeting of the National Roma Council held in the city of Mohács. The technician was standing near a door, when the daughter of a member of the National Roma Council, hit him in the stomach, as she was leaving the room.

The mother of the aggressor, Jánosné Kis denied any wrongdoing, although her daughter actions were captured on film.

- 4 November 2015: Government could force media to employ secret service agents

Hungarian media is demanding that the government repeal a plan that could force newspapers, television and radio stations as well as online publications to add agents from the constitution protection office (national intelligence and counterintelligence) to their staff, the Associated Press reported.

The Hungarian publishers’ association claimed that if the draft proposal by the interior ministry is passed by parliament, it could “harshly interfere with and damage” media freedom, and would facilitate censorship. The association represents over 40 of Hungary’s largest media companies.

- 4 November 2015: Government official asks to criminalise defamation in media law

Geza Szocs, the cultural commissioner in the Hungarian Prime Ministry, has asked for a modification of Hungary’s media law that would criminalise defamation, in an article for mandiner.hu. Szocs has also asked for a stricter regulation of damages caused by defamatory articles.

The commissioner wrote the piece in response to a series of articles published by index.hu, which criticised the Hungary’s presence at the 2015 Milan World Fair, a project that Szocs was managing.

- 26 October 2015: Journalist told to delete photographs of government official

A journalist working on a profile of András Tállai, Hungarian secretary of state for municipalities, was asked to delete pictures he had taken of the politician eating scones.

“Don’t take pictures of the state secretary while he is eating,” a staff member told the journalist, who works for vs.hu.

The journalist briefly interviewed Tállai, who is also head of the Hungarian Tax Authority, in the township of Mezőkövesd, where the politician started the conversation by asking, “Why do you want to write a negative article about me?”. Tállai then smiled and asked the journalist, “You are registered at the Tax Authority, right?”

- 22 October 2015: Public radio censors interview with prominent historian

Editors at MR I Kossuth Rádió, part of Hungarian public radio, did not broadcast an interview with János M. Rainer, one of the most acclaimed historians on the 1956 Hungarian revolution.

“We don’t need a Nagy Imre-Rainer narrative!” was the justification given by one of the editors to censor the content, the reporter who interviewed Rainer claimed.

- 17 October 2015: State press agency refuses to publish opposition party press release

Hungarian state news agency MTI refused to publish a press release issued by Lehet Más a Politika (LMP), an opposition parliamentary party.

In the press release, LMP criticised MTI by stating the Hungarian government is spending more money every year on the news agency, yet MTI fails to meet the standards of impartiality and is being transformed into a government propaganda machine.

- 7 October 2015: National press barred from asking questions at conference

Hungarian journalists were not allowed to ask questions at a press conference held after a meeting between the Hungarian president János Áder and the PM of Croatia, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic.

Only international journalists from Reuters and the Croatian state television were allowed to ask the politicians questions.

17 Nov 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, mobile, News

In February, journalists working at Hír TV, a Hungarian television news channel, and the daily Magyar Nemzet faced a difficult decision: they had 48 hours to decide whether to accept a job offer by the Hungarian public media. If they stayed, they found themselves “persona non grata” in the government circles. Even worse, their jobs and professional future became uncertain.

The story began when the Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán had a fall out with his friend and long-time ally Lajos Simicska. The wealthy businessman – owner of a considerable media portfolio, with the Hír TV and Magyar Nemzet being the most important outlets – was the closest supporter of Orbán for 35 years.

There are many speculations, but nobody quite knows what the real reason for the dispute between the two is. The conflict became public when Simicska commented in the opposition-friendly newspaper Népszava that there will be a “total war” if the government adopts the so-called media tax that would affect his media interests.

As a reaction to Simicska’s comments, a number of his media executives resigned citing “reasons of conscience”. Among them was Gábor Liszkay, the editor-in-chief at the Magyar Nemzet, the second largest daily newspaper in Hungary, who took the paper’s entire senior management with him.

This was the moment when Simicska – who, until this point was known for his extremely discreet way of handling his business interests – went public and repeatedly called Viktor Orbán a “prick”. He also insinuated that Fidesz might murder him.

“On that day, without any formal procedure, they effectively fired the 250 people from Hír TV from the Regime of National Cooperation,” Péter Tarr, the deputy director of Hír TV, said in an interview.

In a few days, journalists and staff members, who until that point were close supporters of the Orbán government, were seen as “traitors” and “enemies” by the government. Their image became nearly as bad as the opposition journalists regularly labeled as “liberal”.

MTVA, the Hungarian public media facing criticism for being the mouthpiece of the Fidesz government, somehow obtained the names and salaries of Hír TV staff. Soon many journalists working at media outlets controlled by Simicska received well-paid job offers from MTVA.

“Nearly every staff member was offered a new job with considerably better pay, and the actual offer depended on his or her status within the editorial team, professional experience and reputation,” a member of senior management at Magyar Nemzet who wished to remain anonymous told Index on Censorship. “They clearly tried to collapse the media outlets controlled by Simicska.”

Some staff members said that the media portfolio controlled by Simicska is a sinking ship, and they should accept the offer while they can. “The curtains will soon fall and they will pour salt into the earth where the television once stood,” recounted Tarr.

“The strategy was to attract the key people and to wait for the editorial teams to collapse like a domino,” our source said. “They didn’t want to spend too much money. They speculated that later the majority of the journalists will appear on the job market anyway, and at that time they will be able to negotiate on totally different terms.”

Although many important staff members jumped ship from both Hír TV and Magyar Nemzet, the editorial teams managed to do the daily workload.

Once things calmed down, both media outlets found themselves free of the constant government control they were previously used to. Nobody from the Fidesz communication staff held meetings with the Hír TV senior management, instructing them who they should invite, what type of programming they should produce or what questions they should ask. As for Magyar Nemzet, the “commissars” (people who clearly had a political mission) disappeared from the editorial rooms.

“After March 15th […] we were free to decide all of this for ourselves and we now keep ourselves to the so-called BBC principles of professional journalism,” explained Tarr in the interview.

“There is a sense of freedom in the editorial room,” our source working at Magyar Nemzet said, adding: “There are no expectations that lead to self-censorship, nobody has to write things he considers problematic from a professional point of view.”

If the complete takeover failed, the government will make the life of journalists as hard as possible. “Some top officials refuse to talk to Magyar Nemzet, and the lower ranking government clerks are obeying the orders they received from the top,” the journalist said. “We can use only a few people from the government as sources.”

“At the public media, there are instructions that journalists working for Magyar Nemzet can not be invited, or employed. Before, I was invited very often to comment on foreign policy issues,” another senior staff member working for Magyar Nemzet told us. “Now I receive no invitations.”

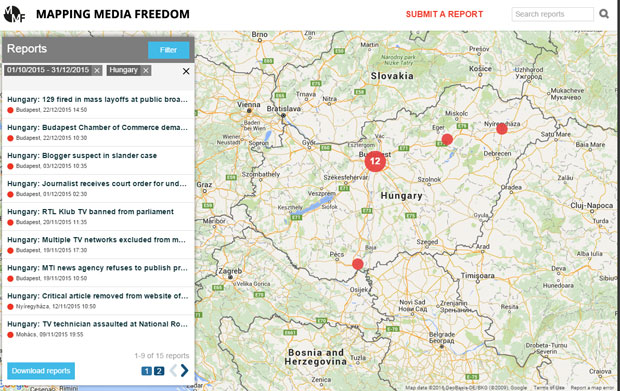

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

1 May 2015 | Denmark, European Union, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Macedonia, mobile, News, Poland, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom

As we approach World Press Freedom Day, the right to freedom of expression will again be celebrated as an inalienable European value across the continent — by the public, the media and politicians alike. But to many, this will mean little more than engaging in a well trodden mental routine. We hardly consider the difficulties that freedom of expression faces in practice.

In the first part of 2015, more than a third of journalist killings in the word took place in two European countries; France and Ukraine. If it is true that Europe’s reactions to the Charlie Hebdo attack — the majority of them very emotional — were salubrious, they simultaneously gave rise to ambiguous situations. Many of the leaders that will on 3 May reaffirm their commitment free expression, supported the same message by taking part in the historic march in Paris on 11 January.

But upon seeing Angela Merkel, some were also reminded that Germany continues to treat blasphemy as a crime — as do Denmark, Spain, Poland and Greece, among others. Ireland, whose Enda Kenny was also in attendance, has a constitution which specifically mentions blasphemy and in 2010 enacted a new law against it. All these European countries defend themselves by saying that they do not apply their laws against “blasphemers”. That argument does not carry much weight when it comes to opposing those countries — Saudi Arabia, Iran, various Asian countries — that have tried to turn blasphemy into a universal crime recognised by the UN.

Spain’s Mariano Rajoy too marched in solidarity, but his government has taken steps to promote changes in the penal code that would “represent a serious threat to freedom of information, expression and the press”.

And what was Viktor Orban doing in Paris? The Hungarian president has reunified Hungary‘s public media so as to better bind them to his own party. Despite being the leader of an EU country, Orban has followed Vladimir Putin’s example. In this experimental model, the Andrei Sakharov Center and Museum is no longer ordered to close as it was in the old days, but rather fined 300,000 roubles (€5,000) for failing to register as a “foreign agent”. One day brings an announcement of compulsory registration for bloggers in Russia; another day, harassment against Russian and Hungarian NGOs perceived as “unpatriotic”.

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutohlu traveled to Paris, only to later label Charlie Hebdo’s post-attack issue a “provocation”. A reminder: Turkey is an EU candidate country where dozens of journalists have been sentenced to prison, and where various internet sites, including those that dared to reproduce some of Charlie Hebdo’s caricatures, have been blocked.

But also present at the march, were various representatives of European journalists — myself included. Just behind the Charlie Hebdo survivors, we carried a banner with the message “Nous sommes Charlie”.

Walking next to me was Franco Siddi, of the Italian National Press Federation. He talked to me about how imprisonment for defamation is still a possibility in Italy, though the European Court of Human Rights has ruled it a disproportionate punishment.

In my home country Spain too, this possibility of imprisonment remains, even if under Spanish jurisprudence freedom of expression consistently prevails over the demands of plaintiffs. In Italy, the situation is the same, yet my Italian colleagues point out that in 2014 alone, 462 journalists in the country were threatened with legal action for alleged acts of defamation. And while the current proposal for reform being considered foresees eliminating the possibility of jail time, it increases the potential fines.

This is not the only potential legal threat facing European journalists. Long before 9/11, there existed a reflexive habit of passing “urgent” laws under security pretexts, as in the UK during the most difficult years of the Northern Ireland conflict. The current model is the United States’ Patriot Act, which has recently been discussed in France. Meanwhile, in Britain and Spain are debating what free expression activists describe as “gag laws”. In Macedonia, the sentencing of the investigative journalist Tomislav Kezarovski to two years in prison under one of these security inspired laws stands out as a warning sign.

Against this worrying backdrop, across Europe journalists, freedom advocates, campaigners and even politicians are standing up for press freedom. When Gvozden Srecko Flego, member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, recently highlighted the cases of Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Azerbaijan as particularly problematic, he also suggested a countermeasure. He recommends “organising annual debates […], with the participation of journalists’ organisations and media outlets” in the respective parliaments of each state.

Media concentration, one of the most serious challenges to media pluralism and free expression in Europe, is being tackled. One proposal, which some international bodies have already accepted, would create a “Media Identity Card” requiring owners to publicly identify themselves and thus create an environment of more open and transparent media ownership.

When defending freedom of expression as a European value, we cannot allow ourselves to simply fall in into mental routines. This World Press Freedom Day we need both words and actions.

Paco Audije is a member of the Steering Committee of the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This column was posted on 1 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org