20 Dec 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Serbia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”97095″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]After more than twenty years of investigative reporting, one of the most popular and trusted local weeklies in Serbia, Vranjske Novine, was forced to shut down. It’s founder and editor-in-chief, Vukasin Obradovic, went in hunger strike a day later. He stressed that the fight for media freedom in Serbia was becoming meaningless, and that his move was one of a desperate journalist. The shut down of Vranjske is not a story of print media struggling in the new digital landscape. Something much more sinister appeared to be afoot.

Vranjske Novine was a local newspaper in the southern town of Vranje, but it was considered a paper of national importance.

“Vransjke wasn’t shut down because they didn’t have readers,” Andjela Milivojevic from the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia (CINS) told Index on Censorship. “They were shut down because the state did everything in their power to shut them down.”

Vranjske didn’t have it easy for years. It was facing threats, political pressure, financial difficulties and its journalists were often labelled as foreign mercenaries by pro-government media. In recent months Vranjske was subjected to investigations by the country’s tax authority and Obradovic received threats saying that they would continue to find something that would discredit the paper. It left him with no other choice than to stop his life’s work.

Three months earlier the paper had published an interview with a former director of the local tax inspection agency, a whistle blower, who revealed corruption. “We think this was the trigger,” said Milivojevic. Obradovic had to stop his hunger strike a few days later because of health problems. He planned to keep the Vranjske website open, but in early December he was forced to close that down as well due to a lack of financing.

Vranjske struggled for years. Their applications for government funds, specially allocated for journalistic productions of public interest, were consistently denied. Instead, subsidies went to pro-government media, Milivojevic explained. “For example, the money would go to a TV station owned by the son of a local politician”.

To Milivojevic and other independent journalists, the Vranjske case stands for everything that is wrong in the Serbian media landscape. And the moment Vukasin Obradovic announced his hunger strike was crucial.

“That was the trigger that moved all of us, because we just couldn’t accept that a journalist who had survived Milosevic, is forced to go in hunger strike in 2017,” she said.

Obradovic is a prominent journalist in Serbia and the former president of the Independent Journalists Association of Serbia (NUNS). As founder and chief-editor of Vranjske his career dates back to the 1990’s when Slobodan Milosevic ruled the country, then Yugoslavia. “They did stories that were important for the whole country, from war crimes during the 1990s to issues we have today,” said Milivojevic. “Stories that were awarded, stories that we all talked about.”

That same night about a hundred journalists and activists gathered in front of the parliament building in Belgrade, to show their support to Obradovic and his Vranjske. They carried banners reading ‘I stand with Vranjske’. It was the birth of the Group For Media Freedom, aimed to address the lack of media freedom in Serbia.

“We need to do something that will wake up citizens,” Milivojevic, who is one of the initiators, explained. She emphasised that it is not just an issue for journalists, but for all the Serbian citizens. “This is a fight for freedom of speech, and at the end of the day this concerns every single citizen,” she said. “We are fighting for a free democratic society in which we all can do our jobs normally.”

According to Reporters Without Borders’ annual World Press Freedom Index media freedom in Serbia has suffered “ever since Alexandar Vucic, Slobodan Milosevic’s former information minister, became Prime Minister in May 2014.” Serbia was ranked 66th, seven places down compared to 2015.

Vucic was elected president of Serbia in April 2017. During a protest outside the presidential building in Belgrade, several journalists faced violence by government security guards, but to date no one has been held responsible. “The public prosecutor said that there was no violence,” says Milivojevic. “But we have pictures showing a big man holding journalists, pushing them, holding them by the throat. We could see it with our own eyes.”

The Group for Media Freedom has compiled a list of demands that they’ve sent to government officials including the Prime Minister, Ana Brnabic.

The group has so far organised panels and debates. There was a 24 hour media blackout during which several independent media organisations and NGOs blacked out their websites to show what it would look like if there was no free media at all. But most importantly, they are going around the country, to smaller cities, to reach ordinary citizens. Handing out flyers and talking to people about what free media means for them, Milivojevic explained.

“People will never hear about these problems in mainstream media because they are all controlled by the ruling party,” Milivojevic said. “So we have to go on foot to the citizens and tell them what is happening. If they would know how much money is spent on corruption, how many people are employed without public competition or that the mayor of Belgrade has problematic assets, they would never vote for the ruling party.”[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/hHytKR7rtEw”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

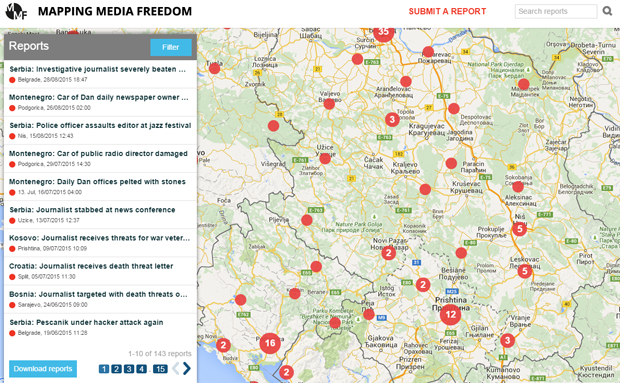

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified more than 3,700 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Sep 2015 | Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Montenegro, News and features, Serbia

“Media has a significant role in the theatre of the absurd,” a participant in a conference on the security and protection of journalists in western Balkan countries claimed.

Media workers and representatives from journalists’ associations in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro joined representatives of international organisations in Sarajevo in June 2015 to debate key issues facing the media in the region: attacks on journalists, impunity, the effectiveness of the legal system and institutional mechanisms to create a safe environment to work in.

Conference participants said media freedom is deteriorating and assigned responsibility for the decline on governments in the region, local media ownership and, especially, international institutions and organisations.

Goran Miletic, programme director for the western Balkans at Civil Rights Defenders, an NGO working in the area, said that in 2004 some of the international organisations decided to withdraw funding from local media to focus on other projects. Miletic said that reduced level of funding for media was a lost opportunity to prevent human rights abuses and further democratise the region.

International funding is vital to professionalising the media, which cannot rely on local government support. “If we analyse research on what people think of human rights defenders or journalists, they are often characterised as spies, foreign mercenaries, or enemies of the state,” said Miletic.

A lack of media plurality and news illiteracy were identified as concerns that have had a detrimental effect on the advancement of press freedom and professionalism in the region.

“Media freedom is once again one of the key challenges for the region,” said Andy McGuffie, head of the communication office of the Delegation of the European Union to Bosnia and Herzegovina and a European Union Special Representative.

Presidents of journalists’ associations focused on attacks on journalists and the effectiveness of the legal system and institutional components. Addressing the current situation in Croatia, Zdenko Duka, then president of the Croatian Journalists’ Association, underlined that “fortunately, [in recent months], there have not been too many physical assaults. Comparing assaults and threats against journalists to other countries in the region, the situation in Croatia is better.”

Croatia has a checkered history on media freedom. During the 1990s journalists were widely targeted and were under surveillance by the secret service. In the 2000s, the journalist Ivo Pukanic, was assassinated in a bomb attack at his Zagreb office. Though a court convicted six men for the murder, the person who ordered the crime has not been brought to justice.

Duka emphasised two 2014 physical assaults: an incident in Rijeka in which football club officials attacked a journalist and a photographer and the brutal attack on journalist Domagoj Margetic who was assaulted by several people near his home in Zagreb. Margetic sustained head injuries as a result of the attack, for which he received medical treatment.

Sanja Mikleusevic-Pavic, a journalist from Zagreb, agreed with Duka. “Croatia is in a much better situation than other countries,” she said. Key reasons for this include the Trade Union and the Journalists’ Association, which are very well organised and powerful, but most of all, the key role played by the public broadcaster HRT. “HRT is a strong, independent and professional public broadcaster,” said Mikleusevic-Pavic.

From her point of view, the main threat to independence and professionalism are pressures from tycoons and politicians, which, in her experience, are significant. The case of Croatian TV broadcaster RTL, which was found guilty of slander for airing a live show during which Croatian Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic accused Zagreb Mayor Milan Bandic of corruption, sets a negative precedent, particularly because another TV station that aired the same statement was not charged. As punishment, RTL has been ordered to pay 6,500 euros to the mayor.

Croatia’s new criminal code presents another obstacle to media freedom. It includes Article 148, introduced in 2013, which establishes an offence of “humiliation”, “shaming” or “vilification”. Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso said the article would allow judges to sentence a journalist if the information published is not considered being in the public interest and “for the court, it is of little importance that the information is correct – it is enough for the principal to state that he felt humbled by the publication of the news.”

In April 2014, Jutarnji List journalist Slavica Lukic became the first Croatian journalist to be prosecuted under the article. She was found guilty of vilification. Lukic reported that a company had economic problems despite the substantial public funding it received. The company stated it felt “humiliated” and the judge fined her 4,000 Euros.

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, said in a letter to the Croatian officials that the current legal definitions of “insult” and “shaming” are “vague, open to individual interpretation and, thus, prone to arbitrary application.”

Duka said that there are more than 40 criminal insult cases pending against journalists in the country and this is clear evidence that “truth can be punishable.” Furthermore, he believes judges are not well prepared for defamation, slander and libel cases. Defamation in Croatia has not been decriminalised as it has been in Montenegro, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“The situation in Serbia is alarming. As long as there is a brutal assault on journalists, we cannot talk about freedom of speech and media freedom,” Vukasin Obradovic, president of the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia (NUNS), said in a speech at the conference.

From 2008 to 2014, Serbia has seen a total of 365 physical and verbal assaults, intimidation and attacks on the property of media professionals. Since May 2014 alone, Index’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom project has received over 48 reports of violations against Serbian media, including attacks to property, intimidation and physical violence.

In his talk, Obradovic described several incidents to illustrate the media situation in Serbia. On 14 April 2007 a bomb exploded outside the apartment of journalist Dejan Anastasijevic. No one was injured. In a statement to international media, Anastasijevic said: “It was just before 3 am on Saturday when a hand grenade went off outside the bedroom window of my Belgrade apartment, filling the room with smoke and shards of glass, leaving shrapnel holes on the ceiling and walls — some only inches above the bed. Despite the damage, we were lucky: When the police arrived, they found a second unexploded grenade on the sidewalk nearby.”

Anastasijevic was targeted because of his investigative reporting on crimes in the former Yugoslavia and criminal syndicates in Serbia, local media reported. The most recent attack followed Anastasijevic’s criticism of a lenient verdict for members of Serb paramilitaries called “Scorpions,” journalists associations said. The case has still not been resolved.

Obradovic emphasised that attacks on journalists in Belgrade often get more attention than violations that take place outside the capital.

Vladimir Mitric, a journalist from the town of Loznica, has been under police protection since October 2005 after being subjected to a brutal assault. He was attacked as he entered his apartment and struck with a blunt instrument from behind several times. He ended up with a broken hand and was very badly bruised all over his body. He is disabled as a result of that attack.

“I live under police protection that I was granted by court, not police, at my request, which is important,” said Mitric in an interview with SEEMO. A former police officer was identified as the attacker and was sentenced to six months in jail by the Loznica Basic Court. The Belgrade Court of Appeal later doubled the sentence.

However, a few months after the trial, Tomislav Nikolic, the president of Serbia, granted amnesty to the attacker and the remainder of his sentence was vacated. Threats against Mitric continue despite 24-hour police protection. Human Rights Watch reported: “The person making the threats was accompanied by a police officer who had been responsible for Mitric’s protection. The person making the threats was charged with minor offences in September, but at this writing the police officer had not been disciplined.”

Sladjana Novosel, a journalist from Novi Pazar, was targeted three times between September 2010 and March 2013. Novosel was subjected to verbal attacks, shaming and bullying. Police have, so far, failed to pursue investigations of these threats.

In another incident, Davor Pasalic, the editor-in-chief of FoNet, was attacked twice early in the morning of 3 July 2014 as he made his way home from his office. The two attacks left him with cuts and bruises, and four of his teeth were broken or knocked out. After seven months of investigation and zero progress, Pasalic sarcastically said that his case is “no big deal.” But he added that the assault has had no impact on his work.

Obradovic finished his talk by saying that “the impunity and recklessness of institutions obviously encourage attacks.”

Branislava Opranovic, member of the executive board of the Independent Journalists’ Association of Vojvodina (NDNV), focused on economic issues and ownership transparency in the media. She described the lack of ownership transparency in the media, sharing her personal experience. “I have been working for the daily Dnevnik for years and years, but still don’t know who the owner of the newspaper is.” She also mentioned other cases, including one where a man in his twenties wanted to buy nine media outlets in Vojvodina, or the episode where her coworkers were waiting patiently in a line to collect bonuses of 5 Euros despite having not received their salaries.

Though Bosnia and Herzegovina was the first country from the region to decriminalise defamation, in 1999, the situation is no better than in Serbia. Borka Rudic, Secretary General of the BH Journalists Association, said: “The raid of the Klix.ba offices in late December 2014 just proves this conclusion.”

In that incident, police entered and searched Klix.ba’s Sarajevo offices for a recording of a phone call in which the Republika Srpska Prime Minister Željka Cvijanović talks about “buying off” politicians. Local media reported that police were copying material from the newsroom’s computers. The police also seized computers, documents, notes and other items from the offices, according to media reports.

Despite positive developments in the law over the past 15 years, the situation has shown little improvement, as institutions are failing to properly implement new legislation, meaning protection on journalists is weak. Between 2006 and 2014, there have been approximately 400 registered cases of media rights violations, including 40 physical assaults and 17 death threats.

Bosnian journalists use a name and shame strategy, in which the identity of every person who threatens or attacks a journalist is publicised. Rudic said that the most serious incident was the attack of Professor Slavo Kukic, a prominent writer and columnist, who was severely beaten with a baseball bat in his office at the University of Mostar, on 23 June 2014.

Marko, a journalist present at the event, shared his and a colleague’s personal experiences. While working for a public broadcaster they were both victims of constant harassment by one of their deputy editors, receiving no support from senior editors or directors. This resulted in them both being admitted to a psychiatric hospital for mental health issues.

Montenegrin TV host and journalist, Darko Ivanovic, told how one of his country’s prominent politicians stated: “it is customary law to hit journalists,” when asked why he slapped a journalist.

Over the last few years Ivanovic has had his car vandalised on a number of occasions, though only one incident resulted in the arrest of a suspect, who admitted the vandalism. However, when interviewed by Ivanovic, the suspect admitted that the police gave him 5 Euros so he confessed to the crime. “There is always someone found guilty, but usually they’re not the real perpetrators. And this puts into the question the effectiveness of the system,” Ivanovic said.

Marijana Camovic, President of the Trade Union of Media of Montenegro, said at the conference “the mindset of local politicians is that for them it is impossible that a journalist could be impartial and professional.”

Tabloids in Montenegro are used for smear campaigns. Civil rights activist Vanja Calovic became the victim of just such a campaign by Informer, a daily newspaper. The tabloid’s mid-June attack against the head of the MANS NGO began with the release of a video recording that, according to the paper, proved that Calovic was “an animal abuser” and alleged that she had sexual relations with her dogs.

The NGO Human Rights Action (HRA) highlighted the perilous state of journalism in its report, “Prosecution of Attacks on Journalists in Montenegro”. The HRA outlined 30 cases of threats, violence and assassinations of journalists as well as attacks on media property between May 2004 and January 2014. “Most of these attacks have not been clarified to date. In most cases certain patterns can be observed, for example: victims are the media or individuals willing to criticise the government or organised crime,” the report said.

One-third of all incidents happened in the the last year, which to the HRA shows the atmosphere of impunity is escalating. “Such an atmosphere of impunity threatens journalists in particular, who are often victims of unresolved attacks. If the state treats these attacks passively, it becomes responsible for the suppression of freedom of speech, the rule of law and democracy.”

The assassination of Editor-in-chief of the Daily Dan, Dusko Jovanovic, who was killed in a drive-by shooting on the evening of 27 May 2004, has not been solved nine years later. Damir Mandic, the only defendant in the recent trial, claims he is innocent and accused the police of planting evidence, Balkan Insight reported. Mandic said he was in prison for 10 years although he was innocent, and his human rights had been violated. He remains the only perpetrator to be convicted.

Seven years after the brutal attack that nearly took the life of journalist Tufik Softic, Montenegrin police detained two men suspected of involvement in his attempted murder. For media unions and observers, the detentions were long overdue, but emblematic of the atmosphere of impunity in Montenegro. In November 2007, Softic was brutally beaten in front of his home by two hooded assailants wielding baseball bats. Then in August 2013, an explosive device was thrown into the yard of his family home. The journalist has been provided with constant police security since February 2014.

Besides this atmosphere of impunity that threatens journalists, Camovic spoke of other phenomena. Approximately 80 per cent of all active media workers in Montenegro are not members of any journalist’s association. When asked why they’re not active in the organisations, they had no answer.

In summing up the situation, Ivanovic said that states and political parties deliberately tolerate grey or criminal activities of media owners so they can control them easily.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|