21 Dec 2015 | Asia and Pacific, China, Magazine, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This is an extract from an article in the Winter 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. You can read the article in full here.

The streets of Dongguan in southern China have been quiet of late. In the past, China’s city of sin would hum to the sound of late-night karaoke bars offering more than just an innocent sing-along. Now these establishments have been forced underground or driven out of business entirely. Their chances of a future are not looking good. On 1 January 2016, new regulations will come into effect that dictate appropriate behaviour for the Communist Party’s 88 million members. As part of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, the new rules explicitly ban the trading of power for sex, money for sex, and adultery – but these are the foundations of business in Dongguan.

“In Dongguan, whose reputation, if not economy, practically rests on its skin trade, I’m told by several sources that the trade remains mostly out of sight nearly two years after a television report [led to]a sweeping crackdown,” said Robert Foyle Hunwick, a writer who has visited the city many times to research his forthcoming book The Pleasure Garden: China’s Hidden World of Sex, Drugs and the Super-Rich.

Dongguan is not the only city suffering from this campaign against smut – it has been lights out for many brothels across China. Nor is this crackdown limited to China’s Communist party members, as the January 2016 regulations imply. Instead, it forms part of a broader crackdown on China’s sex industry that has been underway since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012.

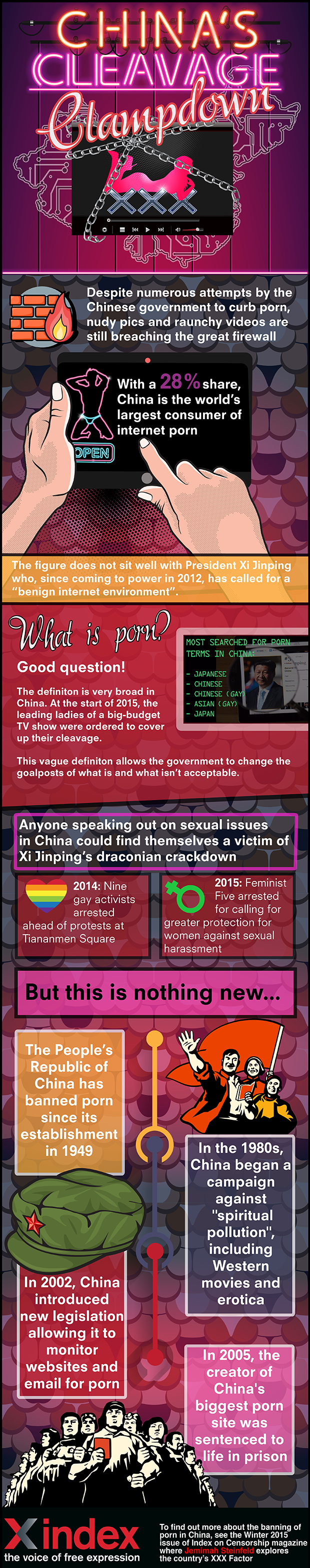

Enemy number one is internet pornography. In the most recent statistics, from 2014, China accounts for up to 28% of the world’s porn consumption, taking the global lead. It’s a statistic that does not sit well with Xi. Shortly into his term in power, he launched his first anti-pornography crusade, calling for a “benign internet environment”. An attempt was made to clear China’s internet of anything verging on pornography. A similar initiative was launched this summer, following the release of a video featuring a couple having sex in a Uniqlo store. It was the usual drill: sites were blocked or removed and anyone caught facilitating the production or distribution of pornography was arrested.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Oct 2015 | Asia and Pacific, China, mobile, News

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

With UK-China relations warming, the president of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping, will pay a state visit to the UK from 20-23 October. The UK government hopes the visit will help finalise multibillion-pound deals for Chinese state-owned companies to contribute to the building of two British nuclear power plants.

Many — including the Dalai Lama — are concerned that Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne are putting the desire for profit above concern for human rights.

Xi may be staying in luxury at Buckingham Palace during his visit, but here are just five examples of how respect for free speech in China doesn’t get past the front door:

1. Locking up artists

The soccer-loving Chinese president is due to visit Manchester City Football Club’s stadium with Cameron during his visit. But will he make time for the new exhibition by Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei in London? We won’t hold our breath.

The major retrospective of the artist’s work is currently on show at the Royal Academy of Arts. Ai — whose work is famous for addressing human rights abuses and corruption — has been harassed, beaten, placed under house arrest and imprisoned.

The current London exhibition almost didn’t go ahead as the British Embassy in Beijing turned down Ai’s request for a business visa in connection with his criminal conviction for tax fraud — an accusation he denies. British Home Secretary Theresa May eventually overturned the embassy’s decision, but only after a mass public outcry. This shouldn’t be the height of the British government’s efforts to address Chinese human rights abuses.

2. The use of online “opinion monitors”

China’s Terracotta Army, the 8,000-strong force of sculptures depicting warriors and horses, was purpose-built to protect emperor Qin Shi Huang, who died in 210 BC, in his afterlife. In the modern day, China’s army of “opinion monitors”, which has been purpose-built to protect China’s current leaders from criticism and dissent, dwarfs anything the Qin dynasty could muster.

Last year, Index on Censorship reported that the Chinese government is expanding its censorship and monitoring of web activity with a new training programme for an estimated two million flies on the firewall.

China’s hundreds of millions of web users increasingly use blogs to condemn the state, but posts are routinely deleted by government employees. In 2012, monitors banned more than 100 search terms relating to the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protest of 1989 and even shut down Google services.

3. Banning books

Often overshadowed by China’s internet censorship, we shouldn’t forget that Chinese authorities have a rich history of restricting free expression in literature. In 1931, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was banned for its portrayal of anthropomorphised animals for fear children would regard humans and animals as equal. During Chairman Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, all aspects of arts and culture had to promote and aid the revolution. Libraries full of historical and foreign texts were destroyed and books deemed undesirable were burned.

The country’s post-Mao transition has been marked by a commitment to “modernising”. While the Chinese populace has access to more information than ever before, their leaders’ continuation of banning books on grounds of non-conformity and deviance are anything but modern.

Publications which are still banned — often for perceived politically incorrect content — include the memoirs of Li Rui, a retired Chinese politician and dissident who caused a stir in the CCP by calling for political reform; Lung Ying-tai’s Big River, Big Sea about the Chinese Civil War; and Jung Chang’s best-selling Wild Swans, a history that spans a century, recounting the lives of three female generations in the author’s family.

4. Detaining activists

Recent years have been marked with an intensification of the crackdown on dissent. On 6 March 2015, just days before International Women’s Day, the Chinese government detained a number of high-profile feminist activists. They were accused of creating a disturbance and, if convicted, could have received three-year prison sentences.

The women had been linked to several actions over the years which highlight issues such as domestic violence and the poor provision of women’s toilets, obvious embarrassments to the authorities.

As a result of their detention, China’s small, but increasingly vocal feminist movement was dealt a heavy blow. Demonstrations were cancelled and debate was effectively silenced. Five of the activists were released fairly quickly, but five more were in prison until 13 April, with two being denied treatment for serious medical conditions while in custody.

5. Repressing Uyghur Muslims

China continues to persecute the largely Muslim minority Uyghurs of Xinjiang. A tough system of policies and regulations deny Uyghurs religious freedom and by extension freedom of expression, association and assembly.

The abuse of national security and anti-terror laws to persecute Uyghurs and further deny them freedom of expression was highlighted in the recent ban by the Chinese authorities on 22 Muslim names in Xinjiang in an apparent attempt to discourage extremism among the region’s Uyghur residents. Many children were barred from attending school unless their names were changed.

Ryan McChrystal is the assistant online editor at Index on Censorship

6 Nov 2012 | Asia and Pacific, China

The world’s two biggest superpowers are about to choose their next leaders. While the American battle is laid bare for all to see, in China, Beijing’s new emperor and his closest advisers are something of a mystery.

Chinese flags (Shutterstock)

That hasn’t stopped the rest of the world debating what Xi Jinping (China’s most likely candidate for the new Communist Party chief) and his top officials will mean for the country. So far it’s all guesswork, and there are some widely differing opinions from Xi the reformer, to Xi the hardliner. Here’s a round-up of the predictions from Tokyo to Washington.

Hong Kong

While there is virtually no discussion in mainland media about the new incoming Politburo, Hong Kong-based pundits are free to publish their views. According to AFP, Hong Kong-based website Mirror Books is pessimistically predicting that the new line-up will be dominated by conservatives and not reformers. It predicted the line-up “would include Zhang Dejiang, Yu Zhengsheng, Liu Yunshan, Zhang Gaoli and Wang Qishan, citing sources close to the party.”

Hong Kong political commentator Willy Lam was positive: “This looks like the line-up. It is not one that will be good for reform hopes”.

Australia

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute argues that it will be business as usual under Xi. He won’t be “making any drastic domestic changes”, argues Hayley Channer, because of his “allegiance to the Communist Party.” But compared to current premier Hu Jintao, Xi is “more approachable as well as more confident.” Channer suggests that domestic problems will keep Xi busy and away from acting too feisty in regional politics.

Kevin Rudd, the Chinese-speaking former Australian prime minister, pointed out last month that the new government — likely to be announced on 8 November, two days after the US elections — will have the same key goal as all other Chinese governments since 1949: that is “the new leadership will seek to sustain the political pre-eminence of the Chinese Communist Party within the country.” This will be tough, Rudd says, because of corruption, economic issues, and the need to boost the country’s international standing.

In terms of issues of free speech, Xi will be walking into a much freer China: “Democratic forces within China also now have greater space to operate than used to be the case,” Rudd writes. “There is now a much more open debate about Chinese policy questions in the Chinese media.”

And while the Party itself is off limits and will continue to be so as a topic of public discussion, Rudd suggests that “the public debate, both in the mainstream media, the social media and on the ground through popular protest activity over local decisions, is now a firm and probably fixed feature of Chinese national political life.”

We can only bide our time, he says, to see how much Xi is prepared to allow this develop.

Xi Jinping during a trip to Dublin, Ireland, February 2012. Art Widak | Demotix

Japan

Dr. Satoshi Amako at The Association of Japanese Institutes of Strategic Studies bleakly pedicts that Xi will be more hardline than Hu.

“Some analysts contend that [Xi] will adopt more conservative policies and try to strengthen one-party rule domestically,” Amako says. “ His statements are conservative but reformist, China-centric but internationalist.”

Xi will have to grapple with a number of crucial issues, one of which is the struggle between a growing need among the people for more freedoms and the supremacy of the Party. He says:

China’s open reform policies not only realized economic growth but also generated a sense of rights, and the Communist Party has applied a strong brake to social and political liberation. On the other hand, various steps have been taken to introduce a degree of flexibility. Nevertheless, resistance from minorities, farmer movements, frequent civil and mass protests, civil rights movements aimed at raising public awareness of rights, and expansions of “free spaces” by informal media are now all evident.

Amako, sadly, offers no prediction over how Xi will attempt to juggle this one.

United States

Xi’s strong ties to the military could mean that he will be a “formidable leader for Washington to contend with”, writes Jane Perlez in the New York Times. With an increasingly stronger People’s Liberation Army (PLA), Xi is likely to focus on making China more assertive on the world stage, particularly in Asia, Perlez cites analysts as saying.

Not so, says infamous former US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger. After he held talks with Xi this year he said he was convinced China’s new leader would bring sweeping reforms to the country.

“It’s unlikely that in 10 years the next generation will come into office with exactly the same institutions that exist today,” Kissinger said.

Like Rudd, Kissinger believes internal issues will dominate Xi’s agenda so that he will not be looking for confrontation with the West:

What we must not demand or expect is that they will follow the mechanisms with which we are more familiar. It will be a Chinese version (…) and it will not be achieved without some domestic difficulties.

According to The Diplomat, Xi’s “confidence” — which Channer in the Australian Strategic Policy Institute also referred to — may be good or bad. A. Greer Meisels writes:

It could mean that President Xi may be more difficult to work with, at least from an American perspective, because he may feel as if the U.S. should be more deferential to China and its core interests. On the other hand, he could be easier to deal with because he may have the confidence to make bolder moves on the foreign policy, political, and economic reform fronts.

So again we’re advised to “wait and see”. And we may have to wait some time: The Diplomat warns that it will be at least one to two years before Xi will have amassed enough “political capital” to make his mark.

United Kingdom

The Economist asks if Xi has “the courage and vision to see that assuring his country’s prosperity and stability in the future requires him to break with the past?” In other words, Xi must start to relax the party’s grip on power to deal with the problems facing China today: a slowing economy, corruption and growing social discontent.

Social media and growing incomes have meant people are more willing and able to voice their complaints, and news of protests can now be debated nationwide.

Xi could, the Economist says, privatise rural land and give it to peasants. The judicial system needs to properly address grievances, and “a free press would be a vital ally in the battle against corruption.”

While the magazine concedes this scenario is highly unlikely, it argues that Xi has no choice if he wants a strong a stable China in the years to come.

More on this story:

China will change leaders, but keep censorship

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]