UN report cites serious human rights violations in Xinjiang but ultimately fails the Uyghurs

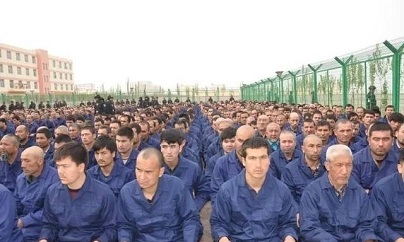

Detainees at a re-education camp in Xinjiang. Photo WeChat/Xinjiang Juridical Administration

“Serious human rights violations” have been committed in Xinjiang and the arbitrary and discriminatory detention of Uyghurs “may constitute…crimes against humanity” according to a controversial UN report that the Chinese government has been trying to quash.

The report also concludes that allegations of patterns of torture or ill-treatment, including forced medical treatment and adverse conditions of detention, as well as allegations of individual incidents of sexual and gender-based violence are “credible”.

What is also abundantly clear is that the report does not make mention of the word “genocide”, something that has left many campaigners unsatisfied.

The UN report goes so far as to push any mention of “suspicious deaths” occurring inside Xinjiang’s re-education centres into a footnote, saying that despite being presented with allegations on these by interviewees it had “not been possible to verify [them] to the requisite standard”. Restricting the ability of the UN to verify claims of human rights abuses is an effective method by which states, such as China, can effectively game the UN’s investigative process. By ensuring the body cannot access the evidence it needs, China can ostensibly shape what the UN can say without exerting any overt control or interference.

Last month it was revealed that the Chinese mission to the UN was lobbying to prevent the release of the report into human rights abuses in Xinjiang. The publication of the report, first commissioned in 2018, had been repeatedly delayed after having been completed in September 2021. Under tremendous pressure from other UN member states, the report was finally made available on 31 August in the last minutes of UN High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet’s term.

The release of the report has not been welcomed by the Chinese government. In its response to its publication, China’s mission to the UN said: “Based on the disinformation and lies fabricated by anti-China forces and out of presumption of guilt, the so-called ‘assessment’ distorts China’s laws and policies, wantonly smears and slanders China, and interferes in China’s internal affairs”.

The attempt to block the report’s publication may come as a shock to some but this incident is only the most recent attempt by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to silence Uyghurs both within and outside China and to discredit those who try to shine a light on their treatment. In the past, the UN has abdicated from its duty to challenge this global campaign against the Uyghurs. The publication of the report is a notable improvement on the UN’s poor track record. But the controversy surrounding the report’s release has left few critics of the UN optimistic about the ability of the organisation to defend Uyghurs in the future.

Michelle Bachelet meets Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2014, photo: Gobierno de Chile

The release of the Xinjiang report reflects a significant departure from the UN’s traditional soft-touch approach to managing its relationship with China. For example, earlier in 2022 Michelle Bachelet became the first UN High Commissioner to visit China in 17 years. While Bachelet praised China’s progress in labour standards and gender rights, she mentioned only in passing the treatment of Uyghurs, which according to credible reports, includes mass enslavement and systemic rape. Bachelet later admitted that her access to Uyghurs was severely restricted, ostensibly because of COVID-19 regulations, but to many her relative silence appeared to validate the Chinese government’s narrative surrounding events in Xinjiang. After her visit, The Global Times, a Chinese newspaper known for inevitably toeing the government line, ran an opinion piece praising Bachelet for changing her perspective on Xinjiang. The piece celebrated Bachelet’s adoption of CCP terminology – highlighting her use of “the term ‘Vocational Education and Training Centre’ instead of the so-called ‘re-education camp’” – and attributed her much-publicised decision not to run for a second term as High Commissioner to pressure she faced after speaking out in favour of China’s counter-terrorism measures.

Bachelet appeared to accept at face value claims that the re-education camps had “been dismantled” and appeared overly optimistic about “China’s stated aim of ensuring quality developed closely linked to developing the rule of law and respect for human rights”. While she expressed some half-hearted concern about the “lack of judicial oversight” in Xinjiang and mentioned Uyghurs she had met before her trip to China who had lost contact with their relatives, her condemnation of the treatment and mass detention of Uyghurs across the region was decidedly muted. Instead she praised China’s “tremendous achievements” in labour and gender rights, an insult to the victims of slave labour and sexual abuse in the camps. She concluded that “there is important work being done to advance gender equality, the rights of LGBTQI people or people with disabilities and all the people among other [groups]”.

China’s mission to the UN now says that the content of the report “is “entirely contradictory to the formal statement issued by [Bachelet]” following her visit. Just like the Global Times, China’s mission is falsely pointing to Bachelet’s Xinjiang trip as an exoneration of the CCP.

Bachelet herself emphasised that her visit “was not an investigation”, which begs the question why it happened in the first place. All her soft touch approach achieved was to grant the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) a significant PR win.

UN whistleblower Emma Reilly

To understand why UN officials like Bachelet have traditionally been so cautious about criticising China, Index spoke to Emma Reilly (left), an Irish former human rights officer at the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Reilly was fired in 2021 after blowing the whistle in 2017, revealing how the UN had for years been passing the names of Uyghurs set to testify before the UN to the Chinese government. Reilly explained to Index that Eric Tistounet from the OHCHR told concerned staff that “not giving them over would further Chinese distrust of the UN”.

One of the names on the list was Dolkun Isa who now resides in Germany. After the UN passed over his name to the Chinese authorities, his remaining family members who still resided in Xinjiang received a visit from the police. His parents later died in a re-education camp in circumstances that are still unclear. Reilly told Index that another person the UN exposed without their knowledge died upon their return to Xinjiang.

After the UN issued a medical report about Reilly, the Swiss police visited Reilly’s house and prevented her from attending a meeting about the issue she had exposed. In doing so, the UN effectively transformed the Swiss police into a tool of CCP censorship.

A tribunal was initiated to investigate Reilly’s case with the assistance of Rowan Downing QC, a former President of the UN Dispute Tribunal and an international war crimes judge. When it became clear that Downing’s ruling would not be favourable towards the UN, he was removed from his position. Downing compared this move to a coup.

Reilly told Index that the UN’s general reluctance to criticise the CCP is based on the misguided assumption that significant concessions need to be made to maintain a friendly relationship with the Chinese government. According to Reilly, it is commonly believed at the UN that increased engagement with the Chinese government will lead it to internalise global norms of human rights. But the opposite appears to be the case. In fact, the Chinese government has proven itself to be a powerful norm maker of its own as it becomes increasingly assertive in the UN.

Rosemary Foot’s book “China, the UN and Human Protection” seeks to explain the paradox of a China that is significantly more prominent in the UN system yet increasingly resistant to many of its central tenets. Most significantly, the Chinese government has sought to bolster the importance of sovereignty and undermine the universal nature of human rights.

For example, China had only used its security council veto power six times before the outbreak of the Syrian civil war. It then used it seven times to block resolutions condemning the Assad regime. The Chinese government believes that the treatment of Syrians, Uyghurs and other groups should be treated as “internal affairs” and economic growth should be seen as the principal means of improving human rights. As Kenneth Roth, the former executive director of Human Rights Watch, recently wrote, “if Beijing had its way, human rights would be reduced to a measurement of growth in gross domestic product”.

In her discussion with Index, Reilly expressed dismay that her case had received the most attention from right-leaning outlets sceptical of the UN project. Other outlets tended to focus on the treatment of whistleblowers rather than the behaviour she was uncovering and the necessity of systemic reform. Like many other UN whistleblowers, Reilly remains committed to the UN project and wants it changed, not abandoned.

Disempowering the UN (like the Trump administration tried to do by making significant cuts after its recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel was rejected) will only empower the Chinese government to fill the vacuum. But the typical relationship the UN has had with the Chinese government swings the pendulum too far in the opposite direction. The UN must not allow itself to become a tool for China to censor its opponents but starving the UN of funds, undermining its mandate, and expecting it to reform is not a tenable solution that protects universal rights and targeted groups, including Uyghurs both in China and elsewhere.

Given the UN’s poor track record of endangering critics of the CCP, does the release of the Xinjiang report suggest the arrival of the kind of systemic reform that Reilly and others have called for?

Critics are sceptical that this recent development (while welcome) reflects a newly assertive United Nations. The next step would be for an independent investigation to be conducted into events in Xinjiang. Calls for such an investigation have also come from within the UN system after 50 UN human rights experts urged the Human Rights Council in 2020 to establish an independent UN mandate to monitor and report on human rights violations in China. According to the OHCHR’s own statement on this recommendation “unlike over 120 States, the Government of China has not issued a standing invitation to UN independent experts to conduct official visits.” However, two years later and progress has been glacial. Considering that the release of a report took almost three years once it was completed and was only possible after overwhelming pressure from other member states, any next step looks like an insurmountable challenge requiring consistent international solidarity and pressure at a time of growing international tension. The Chinese government cannot exert total influence over the UN to silence all of its critics but as demonstrated by the delays of the Xinjiang report, the UN process remains too easy for human rights abusers to impede.

Reilly remains critical of the UN. Now that the UN has officially recognised in its report that the CCP carries out “reprisals against Uyghur and other predominately Muslim minorities abroad in connection with their advocacy, and their family members in [Xinjiang]”, their continued smear campaign against her and refusal to condemn the policy she exposed is an increasingly untenable position.

There is also the question of how permanent the UN’s apparent change of strategy will be. It is notable that Bachelet only felt capable of releasing the report upon her departure from office when she would not have to face the consequences of her decision. Perhaps that now Bachelet is gone, her brief experiment with explicitly calling out the CCP’s human rights abuses will be replaced with business as usual.

If the UN has only just reached the stage of officially recognising that this years long campaign is actually taking place, let alone taking active measures to stop it, who can Uyghurs rely on?

[Index made repeated requests to the United Nations for comment on this article but no replies were received at time of publication.]

To learn more about the censorship of Uyghurs in Europe, read Index’s Banned by Beijing report “China’s Long Arm”: https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2022/02/landmark-report-shines-light-on-chinese-long-arm-repression-of-ex-pat-uyghurs/