[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

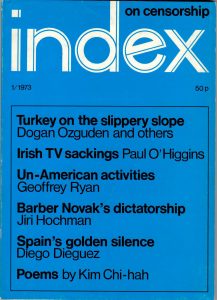

Turkey on the slippery slope, the Spring 1973 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Introduction

On 12 March 1971 the ten-year period of democratic rule that Turkey had been enjoying was brought to an end by a military coup which forced the government then in power to resign, and created in its place a new ‘ strong government’ designed to put an end to what was regarded as ‘anarchy’. This involved the immediate implementation of measures that were directed at anyone suspected of left-wing tendencies (although many of the thousands of people subsequently arrested declared that they were not only liberals but also opposed to communism) and at curtailing many aspects of intellectual life.

In the months that followed the coup scores of newspapers and publications were closed down, thousands of books were confiscated and long lists of banned titles were circulated [see below]. Many hundreds of those arrested have been held in prison for months before going on trial, and frequently they receive maximum sentences for ‘offences’ that were committed before March 1971. The publication of one ‘ offending’ book, for example, can lead to a 7 1/2 year term of imprisonment. People now tend voluntarily to burn their books irrespective of the contents. The flow of information is restricted to official communiques and those journalists who are able to find work are forced to censor themselves. Many other intellectuals will face unemployment if the universities lose their autonomy, as is proposed by a new parliamentary bill, and become subject to government control. This means they may be dismissed if they do not conform to the official line on religion, language and other matters.

In this issue of INDEX we publish material describing some of the changes that have taken place in Turkey in the last two years. Our first article places these developments in a historical context, tracing the present period back, via interludes of freedom, to earlier times of harsh repression. The author describes some of the articles in the Penal Code which, after falling into disuse in the past, are now being invoked, even when their application is inappropriate.

The author is a well-known Turkish journalist at present living abroad.

Dogan Ozgüden: The press under martial law

Under the military regime imposed on 12 March 1971, the life of the press, culture, and the arts in Turkey has been turned into a desert. Today, nobody in Turkey has the right to freedom of expression except a handful of high-ranking generals and big business-men.

After martial law was introduced, all progressive or social periodicals were closed down, hundreds of thousands of books were confiscated, the daily newspapers were compelled to change their policies, the radio television network was placed under the control of army generals, and theatres, cinemas, and all cultural activities were subject to censorship. Hundreds of writers, journalists, editors, actors, actresses, artists, novelists, and poets were detained and even tortured. Tried before military courts established by the martial law headquarters, and threatened with long periods of imprisonment, many of them have already been condemned.

In fact, the freedom of the press, opinion and the arts had already been violated during the previous six years under the rule of the Justice Party, which had engaged in man-hunts and various other forms of repression. At that time, however, the courts of the independent judiciary had been able to act as a brake, and by preventing the execution of these repressive measures they managed to maintain the right to freedom of expression.

But with the imposition of martial law on 26 April 1971, all executive and judicial power was placed in the hands of the generals by an amendment to the 1961 Constitution – and so this guarantee was lost. An amendment to Article 22 empowers the executive to limit the freedom of the press and information gathering for the ‘protection of the territorial and national unity of the state, public order, and the protection of secrecy necessary for national security’. Administrative bodies are thus authorised to confiscate andy publication or censor any correspondance at their discretion. An amendment to Article 121 puts an end to the autonomy of the TRT (Turkish Radio-Television Broadcasting Corporation) by turning it into a governmental body. The heaviest blow to the TRT’s independence was the appointment of an army general as its director just prior to the rewriting of the Constitution.

Historical Background

The situation of the Turkish press is typical of an underdeveloped country. Where the literacy rate is still 48 percent, the press’s function of providing information is limited. Printed matter cannot reach all parts of the country because 65 percent of the 37 million population still live in rural areas Therefore, radio and television still play a vital role in keeping the public informed even in urban centres. Although Turkey is the world’s fourth largest producer of daily newspapers when it comes to the ratio of newspapers to population Turkey is 79th (45 per thousand). The main reason for this paradox is that most of the local daily newspapers are only published in order to earn money by printing official advertising and do not carry information. Outside the big cities, official advertising is distributed by the provincial governors. Five daily newspapers from Istanbul alone account for almost 80 percent of the total circulation of two million; and these newspapers are under the financial domination of the big capital.

The Turkish press was first established in the latter half of the 19th century, although a Turkish printing press had been introduced as early as 1727. In the centralised, despotic structure of Ottoman society with its efficient, absolutist regime, it was impossible to create a western-type organ of opinion. The first newspapers were published in the framework of superficial reforms promised in order to guarantee the interests of western capitalists.

Nevertheless, in time the Young Turks began to publish some clandestine newspapers for the purpose of spreading their ideas; they prepared the Meşrutiyet (constitutional government) movement.

Following the proclamation of Meşrutiyet, in 1908, during a brief period of liberal rule, hundreds of newspapers began to appear with nationalism as one of their main themes. Meanwhile, the first socialist newspapers, Gave (1908-Izmir) and Amele (1909-Selanik) were published. But the dictatorship of Enver Pasha and his associates brought an end to this freedom.

This pattern of liberalisation and repression has characterized the history of the press in Turkey. For example, a new period of freedom followed World War 1, during the national liberation war (1919-22), when various newspapers were published in Anatolia for the purpose of supporting the liberation movement. It was even a social journalist, Hasan Tahsin, who fired the first shot at the enemy in Izmir prior to the national liberation war. Two socialists newspapers Yeni Dünya and Aydinlik, were also published in this period. But with the approach of victory Yeni Dünya was forbidden, and after wards all the writers and editors of Aydinlik were arrested.

Until the end of World War II, the Kemalists in power maintained a rule of terror against liberal, democratic, or socialist intellectuals. Censorship was established in order to clamp down on the press and with the adoption of articles from Mussolini’s Penal Code, all progressive thought was condemned for ‘propagandising for the dictatorship of the working class’. Nazim Hikmet, the world renowned poet, spent thirteen years in jail on this charge.

The liberalisation which followed World War II again paralleled the growth of legitimate political opposition. But after a short while bourgeois politicians decided to eliminate the left from the political arena and banned all socialist publications. The most effective daily newspaper of that period Tan was raided and destroyed at the instigation of the government. Hundreds of socialist or progressive writers, editors and artists were either arrested or compelled to flee Turkey. Meanwhile, Sabahattin Ali, an internationally known Turkish novelist, was murdered as a result of a plot allegedly hatched by the police.

In the 1946-60 period, the influence of the United States over Turkey decisively increased. Ideologically, anti-communism was adopted as a state policy and the most enthusiastic examples of McCarthyism were provided by the Turkish Press and the state owned radio station. Not only socialists, but also liberal-minded writers, thinkers, and artists who dares to criticise the hegemony of the United States were, until 1960, exposed to police terror.

The big daily newspapers which adopted a pro-American and pro-capitalist line profited from advocating that approach. While at the end of World War II the largest circulation of any one newspaper did not exceed 20-30,000, in the 1960’s the circulation of any one newspaper alone, Hürriyet, reached half a million. This was only possible because of the huge financial support every newspaper enjoyed from the state banks and the rising bourgeoisie, which placed advertisements in them.

Nevertheless, the Democratic Party in power found it hard to tolerate such ‘freedom of the press’ even without the voice of the left, and after 1954 the government strengthened its control amending the Press Law. The 1954 regulations imposed heavy fines on journalists convicted of writing articles which harmed ‘the political and financial prestige of the state’. Journalists were jailed and publishers fined as the Democratic Party became increasingly sensitive to criticism of economic problems. These measures alienated many intellectuals and contributed to the 1960 coup.

Climate of liberty

Many of the measures introduced in the 1950s to restrict the press were repealed after the coup that took place on 27 may 1960. Article 22 of the 1961 Constitution safeguarded the freedom of the press and for the first time socialist newspapers and periodicals could be published. In this climate of relative liberty socialist intellectuals found it possible to translate and publish socialist classics. For until that time not only the works of Marx and Lenin, but also books by Western socialists could not be published.

Now that workers and peasants were able to formulate their demands with the large-scale workers’ demonstrations which resulted and with the founding of a labour party and huge masses demanding their constitutional rights and expressing anti-imperialist attitudes, some of the large circulation circulation newspapers opened up their columns to leftist writers in order to obtain new readers. But the publication of anti-imperialist and socialist ideas aroused anger of the businessman who provided the main income of the daily newspapers. Accordingly the publishers of left-wing newspapers were forced to adopt a pro-capitalist and even pro-American policy in their front pages, but at the same time, in order to not lose their left-wing readers, retained left-wing columnists until the martial law of 1971 made this impossible.

In spite of this climate of relative liberty, the 1960 coup and the coalition governments which followed continues to keep the more repressive Articles 141 and 142 in the Penal Code, using them as a threat to left-wing publications. Public prosecutors also used Articles 158 and 159 concerning ‘defamation’ of the President, the Prime Minister, the Government and the security forces.

Although a system of self-censorship was adopted by the press after 1960 and a code of ethics and a Court of Honour were established with the government’s approval, this system was flouted by the mass-circulation newspapers dealing largely in sensation.

Prosecutions for press offences were reviewed by a panel of three judges. But if the journalist was accused of violating Articles 159 or 142, his case was brought before the more serious felony court where he could be sentenced to imprisonment for up to 15 years.

Channels for government influence over the press were not limited to legislation. Turkey had a system of official advertising which subsided the press, and another means of government control lay in the sale of the newsprint: the press has been handicapped by the sale of the essential product at prices higher than the market price.

Although the working journalists had obtained some social guarantees such as minimum wage regulations, compensation for dismissal, social security, etc, the employers dismissed hundreds of journalists, above all left-wing writers and editors, so that freedom of the press was also threatened by the danger of unemployment.

But there were alternative means of publishing open to the left, and periodicals provided the main channel of expression. The first left-wing periodical, Yön, had appeared in 1962 and was able to carry on publication until 1967. At the beginning of 1967, the socialist weekly Ant started up and continued until the 12 March 1971 coup d’etat. During this ten-year period of relative freedom numerous other publications started up.

Meanwhile, apart from the flourishing of commercial publishers, many publishing firms were established during this period with the purpose of publishing socialist literature and scientific research on the socio-economic structure of Turkey. But the government exerted pressure not only on the periodicals, but on the firms that published them as well, and brought hundreds of lawsuits against their publishers, authors and translators. While independent judges acquitted most of them, some people were even jailed – people such as Sadi Alkniliç, Remzi Inanç, Süleyman Ege, Muzaffer Erdost, Hasan Hüseyin Korkmazgil, Mihri Belli, Vahap Erdogdu, Hüseyin Ergün. And hundreds of new legal actions and lawsuits were to become a source of permanent threat to authors, editors and translators. For example, for the authors and editors of Ant alone, the public prosecutors demanded more than 800 years’ imprisonment and for its chief editor over 200 years in all.

In addition, the distribution of these periodicals and books was systematically prevented by the government and right-wing organisations, many books being confiscated as soon as they were published.

Martial Law

With the proclamation of martial law on 26 April 1971, all executive and judicial powers were handed over to six martial law commanders coming directly under the military junta. One of the first actions taken by generals was to close down all socialist and liberal periodicals and newspapers, arresting leftist and liberal intellectuals, writers, artists and journalists. Immediately afterwards, the martial law commanders created eleven military courts in six martial law districts. Hundreds of intellectuals were tried in the newly instituted military courts, and sometimes the charges concerned ‘offences’ committed three or four years earlier, before martial law had been enforced. Even political cases that were previously brought before the civil courts were transferred to the new military courts. According to official statements the public prosecutors have brought since 1965 lawsuits against the publishers, authors and translators of a total of 145 books. Of these books 41 were formally banned and confiscated, 18 were acquitted and trials concerning the remaining 86 are still proceeding.

At first the military authorities prohibited every type of publication, film or theatre performance ‘ discrediting the government or aiming at the overthrow of basic institutions or inciting to rebellion’ and announced that any person selling a forbidden book would be detained. The security forces immediately set about confiscating every type of book, whether they were forbidden or not. The booksellers, in fear of being detained, began sending back all leftist books to the publishing houses and some intellectuals were even reduced to burning their own books. The detention of four booksellers on 2 May 1971 on charges of ‘ having sold forbidden books’ was seen as a threatening example to others. Then on 13 May 1971, the Istanbul Martial Law Headquarters published a list of 77 ‘ forbidden’ books. Yet, the publishers of 16 of the books mentioned had already been tried and acquitted by the civil courts. On 22 October 1971, the martial law headquarters of Istanbul and Ankara issued new lists including 70 ‘ forbidden’ books.

On 1 July 1972, the Third Military Court of the Ankara Martial Law Headquarters decided to confiscate 138 books on the following pretext: ‘ In each search made at the hiding places of ” anarchists”, three kinds of materials have been found: (1) arms, (2) ammunition, (3) leftist publications. These books contain propaganda for communism and have played a most important role in leading the country towards anarchy’. According to the Turkish Press Code then in force, a book could not be confiscated six months after publication date. But the military rulers ignored this law and confiscated not only socialist literature, but even a history on the Ottomans, the Kurds and the Persians, Serefname, written 350 years ago, as well as the Invisible Government, which was about the CIA and had been published before the introduction of martial law. On 28 July 1972, some 3,000 policemen headed by civil authorities empowered by a decision of the Istanbul Martial Law Headquarters raided 30 publishing houses in Istanbul. They confiscated between 250,000 and 500,000 books (650 titles, including some by Agatha Christie) and detained over 50 publishers, distributors and booksellers.

Under this pressure, freedom of the press, opinion and the arts has been completely destroyed in Turkey. All progressive publications have been closed down. The military authorities have applied strict censorship to remaining publications. All newspapers have been compelled to use insulting words in describing resistance movements. It has been forbidden to publish any information concerning the mass arrests or trials apart from that mentioned in official communiques. For example, the daily newspaper Aksam, which had launched a campaign to abolish capital punishment and prevent torture, was closed by the Istanbul Martial Law Headquarters on 17 February 1972 (and also the daily Cumhuriyei). After five days the publisher of the newspaper appealed to the Martial Law Headquarters and pledged to dismiss all left-wing elements and to fight communism, whereupon the newspaper was allowed to resume publication on 22 February 1972.

Nevertheless, the military rulers of Turkey have not found satisfaction in simply modifying the Constitution so as to provide the martial law commanders with arbitrary powers; they have ordered the government and parliament to change all laws and regulations concerning the press and the arts.

According to the amendment to the Code of Criminal Procedure, ‘offences against the State’ must first be investigated in order to decide whether they can be prosecuted or to establish the identity of the ‘offender’. In accordance with the amendment of the Military Criminal Code, if any journalist criticises military expenditure he can be tried in the military courts. The same amendment strictly forbids military personnel from reading political books or from recommending them to other persons in the military. Punishment for such crimes is five years’ imprisonment.

The military-backed government brought the bill amending the Film Control Act before parliament on 13 June 1972. In accordance with the draft bill, the administrative bodies would be authorised to outlaw the making of any film or to ban the showing of any film.

With the amendment of the Duties and Authorities of Police Act, the police forces are empowered to close down any theatre or cinema, to raid the offices of newspapers and publishing houses without first obtaining a court warrant, and the administrative authorities can confiscate any publication or censor any correspondence.

The military are not, however, satisfied with all these amendments and have convinced the political parties of the need to bring in further changes in the Constitution and the Press Code designed to hand more authority to the executive power. If parliament accepted these new amendments, the authorities would be able to brand all thinking citizens as ‘ enemies of the state’ and could try them in the extraordinary security courts which would be instituted under the new provisions.

Meanwhile, some circles are advocating a ‘ press amnesty’ in line with democratic ideals. These demands include only the ‘press offences’ mentioned in the Turkish Press Code and in certain articles of the Turkish Penal Code. The political ‘offences’ mentioned in Article 142 of the Turkish Penal Code are not included in the press amnesty, even though hundreds of intellectuals, journalists and artists have been charged with ‘ propagandising for communism ‘ under that article and have been given prison sentences of seven-and-a-half years for writing one article, translation, poem or speech. While in the other countries that belong to the Council of Europe communist parties are legal and can openly express their views, today in Turkey criticising the social order or publishing a book by Marx or singing a song that reflects the problems of the people is subject to seven-and-a-half years’ imprisonment under the pretext that it constitutes ‘ communist propaganda’.

Until such laws are amended or repealed, the situation in Turkey makes a mockery of its membership of the Council of Europe and its signing the European Convention on Human Rights. Article 9 of the Convention states that ‘ everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought’. It is this freedom that is at issue in Turkey and not the question of an ‘ amnesty’.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Postscript on the Universities

The following is an extract from a report on the situation of the universities and other centres of learning.

The period from 1961 to 1971 could be considered the ‘golden age’ of freedom of thought and expression in Turkey. During this period Western classical and contemporary literature. Marxist and other socialist literature were translated into Turkish and found a ready and expanding market. Young Turkish social scientists and other researchers in particular undertook extensive research into the past and present socio-economic and political structure of Turkey, and their findings were published and widely read. A lively public debate on general social topics and on the particular realities of life in Turkey began to flourish. Universities, radiotelevision institutions and the press played an active role in disseminating the discussion to the masses. From time to time, however, the voices of reaction were raised against the practice of freedom of thought and speech. At first they were unsuccessful in curbing the rising tide of open socio-political discussions of both domestic and foreign affairs, but now, since the coup of 12 March 1971, they have gained the upper hand.

The terror following 12 March was concentrated mainly on the autonomous universities. Reactionary circles started a campaign in which universities were branded as ‘the home of evil and anarchy’. University professors were publicly called ‘ provocateurs of the anarchic activities of the university youth ‘. In an atmosphere where even liberal thought was branded as ‘ communist’, ‘ the purification of the universities’ movement had no trouble starting up and is still going at full strength. Two methods are commonly used in dismissing ‘undesirable’ liberal and left-wing university professors. Either the police raid their homes, confiscating their books and using this as a justification for arresting them, which in turn becomes a justification for throwing them out of the universities.

Or liberal and leftist professors are simply dismissed from the universities. One of the first measures taken by the Erim Government after the March 1971 coup was to change the clause in the 1961 Constitution regarding the autonomy of the universities. Thus, freedom to engage in scientific research was also greatly reduced.

With parliament’s acceptance of the new ‘ University Reform Bill’ further dismissals are made very easy. Already long lists of suspected liberal and left-wing professors are being drawn up and their dismissals discussed in official circles. In this movement, it appears that the prime target will be the Social Science faculties.

The current laws and the 1961 Constitution do not recognise ‘ intellectual crimes ‘. Nevertheless, since 12 March 1971, ‘ intellectual crimes’ have constituted a significantly large percentage of persecutions.

Article 142 of the Penal Code, which was not applied for many years in the past, has now been brought into wide use. This article, which was quoted in Mussolini’s Penal Code thirty years ago, says that:

All those who, in whichsoever form, would propagandise in order to assure the domination of one social class over another, or to eliminate one social class, or in order to overthrow one or more fundamental economic and social institutions existing in the country, or would aim to destroy the political and legal order of the State, are liable to five to 15 years’ imprisonment.

It is interesting to note that in Mussolini’s Penal Code the duration of imprisonment for the above-mentioned offence was from one to five years (Article 272 of the Italian Penal Code). Recently a lecturer in sociology in the Faculty of Political Sciences, Ankara, Dr Ismail Besikoi, who had already been imprisoned for more than a year, was sentenced to 13 years in accordance with Article 142 of the Turkish Penal Code for writing a book on the social structure of Eastern Turkey. There are other similar cases, such as that of Professor Mümtaz Soysal (see INDEX vol. I, no.l p.90).

In the hands of Martial Law Courts, Article 142 is widely applied and words such as ‘struggle’ and ‘class’, which are usually taken out of the context in which they appear are considered sufficient evidence for applying it.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”black” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

The prevalent ideology and the ruling authorities brand almost everyone from the leader of the Republican People’s Party, Mr Bulent Eçevit, to the General Secretary of the Turkish Federation of Trade Unions, Mr Halil Tunç, as ‘ communist’ simply because they use the term ‘social justice’. All liberal and left thought is lumped in one basket and treated in the same way. The majority of the people are now being tried in Turkey not for their deeds but for their actual or suspected thoughts.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Prime Minister Melen on the freedom of press

From Cumhuriyet 7 January 1973

Prime Minister Melen, in reply to a question about whether freedom of the press exists in Turkey, said: ‘ As you know, neither the Constitution, nor the Penal Code, nor the Press Code was modified in a manner which can be said to limit freedom of the press. It follows, therefore, that freedom of the press exists. But, it should always be borne in mind that there also exists Martial Law. The allegations that freedom of the press and the freedom of expression have been restricted are completely unjustified. On the contrary, the press now enjoys many facilities previously denied to it. They can, for example, buy their paper and ink freely.’ When asked of his opinion on the unprecedented number of journalists arrested in recent years, Prime Minister Melen said: ‘ I do not think that they are arrested because they are journalists. They are arrested because they have violated the laws. Do you not think so?’ When reminded that a number of journalists were arrested and eventually convicted for their political views, Prime Minister Melen said: ‘ I think we must agree on the definition of ” freedom of expression “. It, of course, does not mean that anybody can say whatever he likes. If a journalist undermines the foundations of the State or propagates communist ideas in his writings, this must not be regarded as a part of freedom of expression or freedom of the press.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Osman Turkay: International federation of Journalists in Istanbul

Further light on the situation of the press was shed when the International Federation of Journalists (FIJ) held their 11th General Assembly in Istanbul in September last year. Osman Turkay, a Turkish-Cypriot writer living in this country, describes the proceedings.

On Monday, 11 September 1972 the International Federation of Journalists (FIJ) with the participation of about 70 delegates from the member countries, opened the meetings of their 11th General Assembly in Istanbul. The main item on the agenda was press freedom both in Turkey and the rest of the world. Holland and Western Germany had boycotted the General Assembly on the grounds that press freedom was severely restricted in Turkey and in the existing circumstances, Turkish journalists would not be able to speak their minds. This claim was not entirely without foundation, and it came as no surprise to those who did attend the meetings that secret agents of the so-called Melenist democracy had been planted among everybody from the people sitting in the waiting-room to the cleaners of the meeting hall. Detectives posing as journalists were recording every single detail of what was said. The meeting hall was, in fact, under heavy guard.

On one occasion the President of the American Union of Journalists, Mr Charles A. Perlik, missed the coach taking the foreign delegates to the meeting. He was staying at the Tarabya Hotel in Bosphorus. He called a taxi to take him to Cagaloglu, where the congress was taking place, but as he was about to get into the car, three young men came up to him, brought out their cards proving their identity as detectives, and asked whether they could accompany him to the meeting hall. Mr Perlik refused, but he later informed the Turkish Union of Journalists about the incident. The following day while talking with Mr Karl Gustave Mihanek, the International President of the FIJ , he made this protest:

‘The congress has been unsuccessful in only one matter and that was the release of the imprisoned Turkish journalists. I would much appreciate it if Turkish policemen, instead of guarding us here, would go and release those Turkish journalists. Or if our friend the policeman who here, at this very moment, is taking notes as if he were a journalist, would go instead and concern himself with the safety of the Turks outside this meeting hall.’

Heartened by the encouraging speeches of support made by their guests, Turkish journalists began to talk freely. But on one occasion Mr Yusuf Mardin, the acting Director of Press and Broadcasting, was observed in the meeting hall saying quietly to Mr Sadullah Usumi, the President of the Turkish Union of Journalists: ‘You dare to do this here, but don’t forget that when the torrents have gone away, the sands are left behind!’

Although these words contained an open threat, it was disregarded. At that moment the speaker was Mr Bulent Eçevit, the leader of the Republican People’s Party, who was a journalist of longstanding, and he was talking about the importance of press freedom. He remarked that in the countries where freedom of expression was restricted, people were deprived of an opportunity to expound their own ideas about the problems they faced. But Mr Turhan Feyzioglu, the leader of the small party to which Mr Melen, the Prime Minister belongs, shouted out: ‘Take care! He is inciting you against the government!’

On the first day of the International Congress press freedom in Turkey and Greece were given priority. But meanwhile the National Union of Turkish Journalists had issued a report concerning the current situation of the Turkish press designed to coincide with the opening of the International Congress. In this report, the Turkish Union pointed out that freedom of the press was part and parcel of a political whole, and also claimed that changes in the law introduced during the previous two years had restricted that freedom. The report said that both government and economic pressures were brought to bear on the progressive press.’ This new state of affairs, which we hope will be transitional, not only restricts freedom but also attempts to reduce the effectiveness of the press to nil. In these circumstances journalists have had to place controls on themselves to such an extreme degree that they have avoided printing even the most innocent reports.’

On 13 September a delegation of six journalists representing the International Congress visited the four Turkish journalists in Cagmalsilar Prison in Istanbul. Mr Kenneth Morgan, President of the National Union of British Journalists, was in the delegation, and he interviewed the imprisoned journalists. This interview he read out to the Congress the following day, and immediately afterwards the Congress requested the Turkish authorities to release the journalists from prison.

On 15 September, the International Congress of the FIJ ended. It closed with a serious warning to the Turkish authorities, saying that although the situation was different from that in Greece, Turkey might nevertheless find herself placed in the dock by the Council of Europe if she did not change her policy of oppression. In the communique issued at the end of the Congress, the following passage regarding Turkey was included:

‘We call upon the Turkish authorities to respect the freedom of the press and freedom of thought in accordance with the rules and principles of the Turkish Constitution, with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and with the European Human Rights Convention which Turkey has signed. Our Congress wishes to make it known that these principles have been undermined by Turkey and that the political and economic pressures exerted on the Turkish press give cause for concern. Turkey should return to the principles of her constitution and fulfill her international obligations in order to guarantee freedom of the press and freedom of expression.’

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

‘Hope’ fades: How a film jury came to change its mind

On Thursday 28 September 1972 Mr Yilmaz Güney, the famous Turkish film-star, and Mr Abdurrahman Keskiner, the film director, were brought under armed guard into the dock of the Central Criminal Court in Istanbul, to be tried for smuggling a film called ‘Hope’ out of Turkey in order to enter it in the Cannes Film Festival. Meanwhile at the Gold Cocoon Film Festival being held in Adana in Southern Turkey, a majority on the jury had voted in favour of awarding the first prize to another of Mr Güney’s films, entitled Baba (‘The Father’), and they named him Turkey’s best male film star. Osman Turkay comments:

The news appeared in all the headlines the next day and even the state-controlled Turkish Broadcasting and TV Services gave prominence to the story. But things were not so smooth as they appeared. At Adana, the head of the film jury, Mr Sevket Rado, made preparations to leave together with three other members of the jury, and refused to attend the Festival Banquet because he claimed that six of the members of the jury who had voted in favour of Mr Güney were ‘intellectually conditioned people, which is to say that they sat on the jury simply in order to award first prize to an accused man’. Mr Rado said that this was obviously the case because those who had voted in favour of Mr Güney now wanted their voting cards to be burned. The real reason was more probably fears about their sympathies becoming known, such being the formidable power of censorship. However, Mr Rado put the cards into a sealed bag which he then delivered to the authorities.

Although Mr Rado and the three members of the jury had intended to leave Adana in protest, the Lord Mayor and the authorities managed to persuade them to stay and revise the jury’s decision. This they did, meeting the following day at the Lord Mayor’s Palace and altering the decision, which had already been made public, so that Mr. Güney and his film were excluded from the competition. The first prize was now awarded to Karadogan and Mr Cüneyt Arkin was named as the film star of the year. Mr Arkin, however, refused to accept the prize. Despite the ensuing scandal the head of the jury, Mr Rado, was apparently too busy to announce the new results of the Gold Cocoon Film Competition and made no attempt to counter the allegations of hidden censorship.

Meanwhile Mr. Güney was defending himself before the Military Tribunal in Istanbul. Six months earlier he had been arrested and imprisoned in the Selimiye Kişla, which had originally been built by Sultan Selim as military headquarters. He had once before been sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment on charges of communist propaganda. Now he was under arrest for smuggling his film ‘ Hope’ out of Turkey without a licence. The film had been banned in Turkey shortly after they had decided to send it to Cannes. The military prosecutor had asked for a five-year sentence on this charge alone. Yet Mr Güney talked optimistically and full of confidence:

‘From the beginning of my artistic life until yesterday, I did my best to bring the Turkish film industry up to a contemporary level. Yes, I did indeed send out of Turkey a film which was considered to be of great artistic value in Turkish culture. But my ultimate objective was to win an international prize on behalf of my country. It will only be an honour for me to have been punished for this ideal.’

The director of the film, Mr Abdurrahman Keskiner, who was also charged, defended Mr Güney and himself by telling the crowded courtroom:

‘Yilmaz [Güney] and I made this film specially for a competition. It won the Gold Cocoon first prize last year and was warmly praised by the Turkish Press. After that we decided to send it to the Cannes Film Festival. But just at that time the Central Film Commission banned it. We objected to this decision and the Commission lifted the ban. Then a man called Ahmet Saygili came to Turkey from Germany and took the film to the Cannes Festival. But we were too late. So our film was only shown at the Directors’ Festivities where it earned the title of one of the best ten films.’

O.T.

Mr Güney was subsequently released pending police investigations into his case, and his trial was adjourned. Editor.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Seized books

After the proclamation of martial law in Turkey the military authorities issued a series of lists of forbidden books and authorised the confiscation of books from booksellers and publishers. INDEX has received copies of two such lists, of which the one published here is most complete. The books are listed under the names of the publishers that issued them.

ANT Publications

Urban Guerrillas: C.Marighela (translated)

Fascism and the Revolutionary Popular Front: Cetin Özek (Turkish)

Diary of a Guerrilla: Che Guevara (translated)

Fundamental Book of Marxism: E. Burns (translated)

Progressive Movements in Turkey: Y. Sertel (Turkish)

File on Greece: K. Kakalas (translated)

Black Power: S. Carmichael (translated)

The Book of Honour: S. Senel Han (Turkish)

The Giant With Blue Eyes: Z. Sertel (Turkish)

The People’s War in Palestine and the Middle East: N. Havatme (translated)

Capitalism in Turkey and Class Struggles: A.Snurov and Y.Rozaliev (translated)

Like a Novel: S.Sertel (Turkish)

A Handbook of Marxist Economy: E.Mandel (translated)

National Liberation Movements in the East: Lenin (translated)

SER PRESS PUBLICATIONS

Lessons of October: Trotsky (translated)

Selected Works, Vol. II Book 1 and Selected Works Vol. I: Mao Tse Tung (translated)

On Culture and Cultural Revolution: Lenin (translated)

Economic Policy from the Marxist Angle: J.Ibarrolla (translated)

United Front Against Fascism: G.Dimitrov (translated)

Party Struggles in the Mass: Lenin (translated)

Socialist Revolution in Vietnam: Le Duan (translated)

The Theory of Relativity: A.Einstein (translated)

On Youth: G.Dimitrov (translated)

PAYEL PRESS Publications

Arts and Literature: Lenin (translated)

Which Inheritance of Thoughts We Deny: Lenin (translated)

The Development of Capitalism in Russia: Lenin (translated)

My Friend Che Guevara: R.Rolo (translated)

The Economic Content of Popularism: Lenin (translated)

Socialism and Political Struggle: G.V.Plekhanov (translated)

Peasants’ Struggles in Germany: F.Engels (translated)

Manuscripts of 1844: K.Marx (translated)

People’s Comintern in China: Helen Marchisio (translated)

The Establishment of Socialism in the Soviet Union: A.Fadeyev (translated)

Inferno of Treblinka: V.Grossman (translated)

People’s Democracies: P.Paraf (translated)

SOCIAL Publications

Fundamental Problems of Marxist Ideology: G.V.Plekhanov (translated)

New Democracy: Mao Tse Tung (translated)

Cement (novel): Gladkov (translated)

Fundamental Principles of Socialist Philosophy: G.Politzer (translated)

Labour, Price and Profit: K.Marx (translated)

Dialectical Materialism: Kusinen (translated)

National Liberation Movements in Africa: B. Davidson (translated)

Classes in Capitalist Societies: M. Bouvier (translated)

Marxism and Language: J.V.Stalin (translated)

German Ideology: K.Marx (translated)

ÖNCÜ (Vangard) Publications

Politics and Philosophy: Marx and Engels (translated)

Manifesto:Marx and Engels (translated)

Epics of September (poems): G.Milef (translated)

Memoirs 1893-1917 (seized while printing at printers’ plant): Lenin (translated)

From Hegel to Marx-Studies of Ideological Developments in Marx (seized while printing at printers): (writer unknown)

Scientific Communism (seized at the printers): (writer unknown)

An Anthology of Soviet Poets (67 poets): Compiled by Attila Tokatli and Ülkü Tamer

Friedrich Engels: P.Louis (translated)

Women and Communism: Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin

An Introduction to the Criticism of Economic Politics: Marx (translated)

Sociology of Marx: H.Levebre (translated)

The First International: J.Duclos (translated)

Philosophy of Hegel and the Historical Consciousness of Marx: M.Beer (translated)

Gracchus Babeuf: J.Lepine (translated)

Social Classes in Turkish Society: Ibrahim Türk (Turkish)

TOPLUM Publications

Socialist Turkey: A.Faik (Turkish)

Letters: Lenin (translated)

The Capitalist Exploitations: A.Barjonet (translated)

Women and Socialism: A.Bebel (translated)

Chinese Revolution and Aftermath: J.J.Brieux (translated)

What is meant by Marxist Philosophy?: W.Rochet (translated)

Disintegration of the Left in Turkey: Dr C.Yetkin (Turkish)

The Forest: W.J.Pomeroj (translated)

Strategy and Tactics for Youth: A.Faik Cihan (Turkish)

HABORA Publications

Marxism in the Twentieth Century: R.Garaudy (translated)

Lenin: J.Stalin (translated)

The American Communist Party: Ahmet Agin (Turkish)

The Leipzig Trial: E.Fischer (translated)

Anarchism: Kropotkin (translated)

Newspapers & periodicals

This is a provisional list of newspapers and periodicals that have been closed down by the authorities for varying periods of time. The date of the closure order is given on the right.

Cumhuriyet: 28 April 1971

Aksam: 28 April 1971

Işci Köylü, Devrim, Proleter Devrimci Aydinlik: 29 April 1971

Türkiye Solu, Aydinlik Sosyalist Dergi, Dagyeli

Ant, BugUn, Babialide Sabah: 30 April 1971

Emek: 2 May 1971

Vatandas, Cukurova: 27 May 1971

Ittihad: 8 June 1971

Dünya, Yeni Asya, Bizim Anadolu: 8 July 1971

Four newspapers in Diyarbakir: 10 August 1971

Halkin Dostlari: 13 September 1971

Hüryol, Adalet, Vatandas: 13 September 1971

Ortam: 8 October 1971

Ege Ekspres, Günaydin: 12 October 1971

Bizim Anadolu: 24 October 1971

Yanki: 8 November 1971

Demokrat Izmir: 23 November 1971

Aksam: 17 February 1972

Baris: 13 March 1972

Günaydin: 16 March 1972

Son Havadis: 2 May 1972

Yeni Gun: 7 June 1972

Toplum: November 1972

Yeni Ortam: November 1972

Hürriyet: January 1973

Detained and arrested

These are some of the journalists, writers and faculty members who have been detained or arrested.

Journalists

Cetin Altan, Dogan Kologlu, Ilhan Selcuk, Erol Türegtün, Oktay Kurtböke, Gafsan Seyfettinoglu, Süleyman Galioglu, Dogan Avcioglu, Ilhami Soysal, Nurettin Pirim, Ali Sirmen, Tanju Cilizoglu, Altan Ӧymen, Osman Saffet Arolat, Emil Galip Sandalci, Esin Talu Celikkan, Yasar Uçar, Vahap Erdogdu, Mete Dural, Özer Esmer.

Writers

Fakir Baykurt, Yasar Kemal, Samin Kocagöz, Aziz Nesin, Nevzat Ustün, Hasan Izzettin Dinamo, Fazil Husnü Daglarca, Dursun Akçam,Sabahattin Eyüboglu, Azra Erhad, Tahsin Saraç, Sevgi Soysal, Nihat Behram, Siar Yalçin, Ali Faik Cihan, Mehmet Emin Bozarslan, Musa Anter, Erdal Ӧz, Faik Muzaffer Amaç, Sina Ciladir.

Radio-television employees

Erdal Boratap, Sezai Colakoglu, Ela Güntekin, Sahabettin Kalgay, Semih Sermet, Ayhan Karapars, Fatma Ipek Erkeller.

Translators

Matilda Gökçeli, Seçkin Cagan, Abdullah Nefes, Tektas Agaoglu, Can Yücel.

Publishers-editors

Muzaffer Erdost, Masis Kürkçügil, Ilhan Kalaylioglu, Süleyman Ege, Cigdem Ӧzgüden, Zeki Oztürk, Ramazan Yasar, Bülend Habora, Necdet Sander, Kemal Karatekin, Vedat Günyol.

Artists

Yilmaz Güney, Asik Fermani, Bülend Balakoglu, Turban Selçuk, Muammer Sun, Ayse Emel Mesçi, Zeymep Sagnak, Mustafa Coskun, Avni Yalçin, Vasig Ongören, Erkan Yücel, Ayse Semra Erdogmus, Metin Erksan, Penina Bencoya, Mehmet Keskinoglu, Asik Mahzuni.

University professors’and lecturers

Mümtaz Soysal, Tarik Zafer Tunaya, Ismet Sungurbey, Muammer Aksoy, Bahri Savci, Cetin Ozek, Dogu Perinçek, Ugur Alacakaptan, Bülend Nuri Esen, Cahit Talas, Rauf Nasuhoglu, Burhan Cahit Unal, Nihat Sisli, Oguz Aksu, Behice Boran, Sadun Aren, Oya Köymen, Oya Sencer, Oruç Bilgiç, Mehmet Selik, Ӧzer Ozankaya, Mete Tuncay,

Ismail Besikçi, Idris Küçükömer, Aydin Karagözoglu, FerhanBaydak, Muzaffer Sipahioglu, Caglar Kirçak, Aysel Ӧgüt, Edip Yazgan, Erdem Aksoy, Kemal Erdogdu, Mukbil Ӧzyörük, Adil Özkol, Ugur Mumcu, Halil Berktay, Nuri Colakoglu, Eyüp Cüneyd Akalin, Omer Madra, Ahmet Gürcan Kumrulu.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores 1968 – the year the world took to the streets – to discover whether our rights to protest are endangered today. Including Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy, and Micah White.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]