Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

#DONTSPYONME

Tell Europe’s leaders to stop mass surveillance #dontspyonme

Index on Censorship launches a petition calling on European Union Heads of Government to stop the US, UK and other governments from carrying out mass surveillance. We want to use public pressure to ensure Europe’s leaders put on the record their opposition to mass surveillance. They must place this issue firmly on the agenda for the next European Council Summit in October so action can be taken to stop this attack on the basic human right of free speech and privacy.

(Index on Censorship)

ANGOLIA

Analysis: Angola illustrates the dangers of criminal defamation laws

South African media reacted nervously when a former Sowetan journalist was found guilty this week of criminal defamation. This was not an over-reaction, if the example of Angola is anything to go by. Do we really want to be taking media management lessons from José Eduardo dos Santos?

(Daily Maverick)

AUSTRALIA

Public servants and free speech

On Monday, August 13, Canberra public servant Michaela Banerji lost a case in the Federal Circuit Court before Judge Neville, which has paved the way for her possible dismissal from the Department of Immigration.

(The Conversation)

BAHRAIN

Bahrain activists to test demo ban at U.S. embassy

Bahraini opposition activists, inspired by the success of street protests in Egypt, plan to demonstrate near the U.S. embassy on Wednesday in defiance of a government ban.

(The Daily Star)

BRAZIL

U.S.-Brazil relations face ‘challenge’ under dark cloud of NSA leaks

The United States pledged on Tuesday that Brazil and other allies will get answers about American communications surveillance aimed at thwarting terrorism, but gave no indication it would change the way it gathers such information.

(The Globe and Mail)

EGYPT

Press Freedom at Risk in Egypt

Hopes for press freedom were high after the 2011 revolution ousted Hosni Mubarak, led to an explosion of private media outlets, and set the country on a path to a landmark presidential election. But more than two years later, a deeply polarized Egyptian press has been battered by an array of repressive tactics, from the legal and physical intimidation of Mohamed Morsi’s tenure to the wide censorship of the new military-backed government. A CPJ special report by Sherif Mansour with reporting by Shaimaa Abu Elkhir from Cairo

(CPJ)

FRANCE

Twitter in hot water again in France – this time, for Homophobic Hashtags

The problem with giving into the requests of the government is that, well, you have to follow through. After an altercation with a few advocacy groups and the French government over some anti-Semitic trending hashtags earlier this year, Twitter promised to provide a streamlined access for users ( & the government) to signal inappropriate content. They also suggested that they would be turning over account information of users who use hate speech on the social network so that the French government can pursue those users for violating France’s free speech laws.

(Rude Baguette)

RUSSIA

In Russia only tyrants’ names change

The news out of Russia never seems to be new. The names change, not the essence. Nor does the reaction of Russia-watchers: a deep, hopeless, wordless sigh. As if to say: What’s to be said? Ah, Russia!

(Boston Herald)

Olympic athletes who promote ‘non-traditional sexuality’ will be arrested

Athletes at the Winter Olympics will be arrested if they breach Russia’s controversial ‘gay propaganda’ laws, the country’s interior ministry has confirmed.

(Metro)

Previous Free Expression in the News posts

Aug 13 |Aug 12 |Aug 9 |Aug 7 | Aug 6 | Aug 5 | Aug 2 | Aug 1 | July 31 | July 30 | July 29 | July 26 | July 25 | July 24 | July 23 | July 22 | July 19

Payam Feili (Photo: Nogaam)

Iran’s government has been increasing pressure on writers and artists over the past few years, but its heavy hand does not strike evenly.

Iranian poet Payam Feili, who is a gay man, is the victim of a brutal system. He was fired from his job, his translator’s house was ransacked, and the censors have shunned him.

Isolated in Iran, Feili has dedicated himself to writing. He says he lives among his ideas, a citizen of his mind: “I’m writing on the edge of crisis but I think I am doing fine. I’ve gotten used to life being full of tension, horror, disruption and crisis”.

Born in 1983, in Kermanshah, a city in western Iran, Feili has faced insurmountable obstacles as an author who, with pen as sword, is fighting back against social, cultural and political taboos. Despite the endorsement of renowned Iranian Simin Behbahani and the backing of one of Iran’s biggest publishers, Feili’s work has only once emerged from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance with a seal of approval.

Feili’s first book, ‘The Sun’s Platform’, was published in Iran in 2005, but dozens of other works submitted to the ministry have been refused publishing permission. Payam is blacklisted, not just for his words, but for his sexual orientation.

“They refused my books, one after the other, without any explanation. They have a blacklist of authors who are simply not allowed to publish anything. Even my apolitical non-religious works, works of pure poetry, were banned. There’s nothing scary about them, but the state authorities are afraid of everything”

Observing his sharply delicate words falling from the pages of history unread, Feili began publishing his books outside Iran, knowing all too well that he was endangering himself. Officers from the Ministry of Intelligence ransacked his translator’s house and threatened him, forcing him to sever ties with Feili. After gaining notoriety abroad, the company Feili had worked for fired him without good cause. With the odds stacked against him, Feili insists on exercising his right to freedom of speech.

“If you read my books, it’s obvious I have not succumbed to self-censorship. My poems are bold and fearless. I don’t allow anybody, not me, not others, not even the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to censor my books”

Many are hoping for Rouhani’s presidency to bring around the cultural thaw that characterised Khatami’s two terms. Feili has not been swept up by the wave of hope that has captured his peers.

“Nothing essential has changed. The structure is still the same. It’s a play, a comic and ugly performance. They’re relying on the naivety of people to be able to succeed”

Embittered by 30 years of living in exile within the borders of his country, as a homosexual, and as a writer that challenges the status quo, Feili is now dedicating his time to securing funding to translate his poetry for audiences outside Iran.

“I’ve learned a lot and I know what’s going on in Iran. I know that when my homosexual narrative is woven through my words and there is a Star of David on the cover of my book, the censors won’t even bother opening it to find out what is inside. I just want to be published. I know the audience outside Iran is different, but I just want to be heard”.

This article was reported by Nogaam, a publisher of Iranian books and authors that have been censored, banned or blacklisted. Nogaam relies on donations from readers to publish their books for free download on their website. Payam Feili’s book ‘White Field’ was first published in Persian by Nogaam in London in July 2013. The publisher is currently seeking support to help Payam translate his poems, and fulfil his simple goal of being heard.

I Will Grow, I Will Bear fruit … Figs (First Chapter)

ONE

I am twenty one. I am a homosexual. I like the afternoon sun.

My Apartment is in the outskirts of town. Near the wharf. In a place that is the realm of seashells, the realm of corals, adjacent to the eternal sorrow of the turtles.

My mother lives in the waters. In the remains of an old ship. On a bed of seaweed. Her hair blazes like a silver crown above her head. My mother is always naked. She visits me every now and then. At my apartment in the outskirts of town.

She first crosses the wharf. She floats in the scattered scents of the bazaar. Then she pays a visit to the crowd of fishermen in the seaside cafés. Among their wares, a hidden pearl. And she leaves them and heads for my bed. Of course, along this entire route, she is no less naked.

Poker; that is what I call him. He is my only friend. We met during military training. He is twenty-one. He likes the afternoon sun and he is not a homosexual.

I consider this a threat. I have never talked to anyone about my sexual inclination. In fact, I hide it. Even from my few sexual partners. With them, I pretend it is my first such experience.

My sexual partners are night prowlers. Strangers. Poker is not a night prowler. Poker is not a stranger. And this is chipping away at me from the inside!

Payam Feili

Translated from the Persian by Sara Khalili | This translation appears on Feili’s blog.

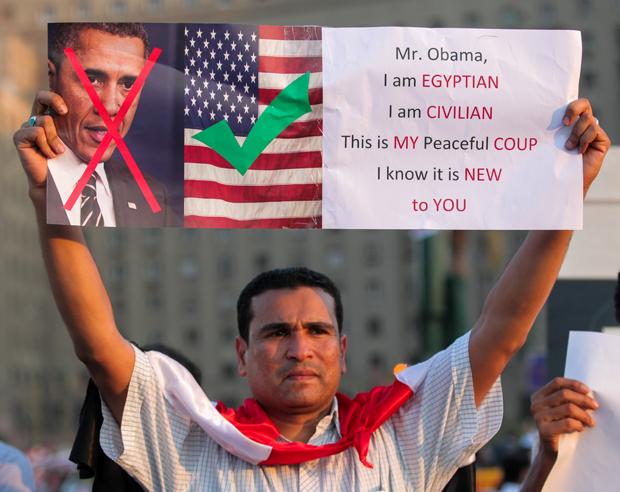

An Egyptian protestor holds a sign showing the anger of some Egyptian people towards the American government. (Photo: Amr Abdel-Hadi / Demotix)

Index on Censorship condemns today’s attacks on protest camps in Cairo and other cities and calls on Egyptian authorities to respect the right to peaceful protest. Live coverage Al Jazeera | BBC | The Guardian

Xenophobia in general and anti-US sentiment, in particular, have peaked in Egypt since the June 30 rebellion that toppled Islamist President Mohamed Morsi and the Egyptian media has, in recent weeks, been fuelling both.

Some Egyptian newspapers and television news has been awash with harsh criticism of the US administration perceived by the pro-military, anti-Morsi camp as aligning itself with the Muslim Brotherhood. The media has also contributed to the increased suspicion and distrust of foreigners, intermittently accusing them of “meddling in Egypt’s internal affairs” and “sowing seeds of dissent to cause further unrest”.

A front page headline in bold red print in the semi-official Al Akhbar newspaper on Friday 8 Aug proclaimed that “Egypt rejects the advice of the American Satan.” The paper quoted “judicial sources” as saying there was evidence that the US embassy had committed “crimes” during the January 2011 uprising, including positioning snipers on rooftops to kill opposition protesters in Tahrir Square.

The stream of anti-US rhetoric in both the Egyptian state and privately-owned media has come in parallel with criticism of US policies toward Egypt by the country’s de facto ruler, Defense Minister Abdel Fattah el Sissi, who in a rare interview last week, told the Washington Post that the “US administration had turned its back on Egyptians, ignoring the will of the people of Egypt.” He added that “Egyptians would not forget this.”

Demonizing the US is not a new trend in Egypt. In fact, anti-Americanism is common in the country where the government has often diverted attention away from its own failures by pointing the finger of blame at the United States. The public has meanwhile, been eager to play along, frustrated by what is often perceived as “a clear US bias towards Israel”.

In Cairo’s Tahrir Square, anti-American banners reflect the increased hostility toward the US harboured by opponents of the ousted president and pro-Morsi protesters alike, with each camp accusing the US of supporting their rivals. One banner depicts a bearded Obama and suggests that “the US President supports terrorism” while another depicts US ambassador to Egypt Anne Patterson with a blood red X mark across her face.

The expected nomination of US Ambassador Robert Ford — a former ambassador to Syria who publicly backed the Syrian opposition that is waging war to bring down the regime of Bashar El Assad — to replace Patterson, has infuriated Egyptian revolutionaries, many of whom have vented their anger on social media networks Facebook and Twitter. In a fierce online campaign against him by the activists, Ford has been criticized as the “new sponsor of terror” with critics warning he may be “targeted” if he took up the post. Ambassador Ford who has been shunned by the embattled Syrian regime, has also been targeted by mainstream Egyptian media with state-owned Al Ahram describing him as “a man of blood” for allegedly “running death squads in Iraq” and “an engineer of destruction in Syria, Iraq and Morocco.” The independent El Watan newspaper has also warned that Ambassador Ford would “finally execute in Egypt what all the invasions had failed to do throughout history.”

The vicious media campaign against Ford followed critical remarks by a military spokesman opposing his possible nomination. “You cannot bring someone who has a history in a troubled region and make him ambassador, expecting people to be happy with it”, the spokesman had earlier said.

Rights activist and publisher Hisham Qassem told the Wall Street Journal last week that “Egyptian media often adopts the state line to avoid falling out of favour with the regime.”

Statements by US Senator John McCain who visited Egypt last week to help iron out differences between the ousted Muslim Brotherhood and the military, have further fuelled the rising tensions between Egypt and the US. McCain suggested that the June 30 uprising was a “military coup”, sparking a fresh wave of condemnation of US policy in the Egyptian press.

“If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck, then it’s a duck,” Senator John McCain had said at a press briefing in Cairo. He further warned that Egypt was “on the brink of all-out bloodshed.” The remarks earned him the wrath of opponents of the toppled president who protested that his statements were “out of line” and “unacceptable.” The Egyptian press meanwhile has accused him of siding with the Muslim Brotherhood and of allegedly employing members of the Islamist group in his office.

The anti-Americanism in Egypt is part of wider anti-foreign sentiment that has increased since the January 2011 uprising and for which the media is largely responsible. Much like in the days of the 2011 uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak, the country’s new military rulers are accusing “foreign hands” of meddling in the country’s internal affairs, blaming them for the country’s economic crisis and sectarian unrest. The US has also been lambasted for funding pro-reform activists and civil society organizations working in the field of human rights and democracy.

Ahead of a recent protest rally called for by Defense Minister Abdel Fattah El Sissi to give him “a mandate to counter terrorism”, the government warned it would deal with foreign reporters covering the protests as spies. As a result of the increased anti-foreign rhetoric in the media, a number of tourists and foreign journalists covering the protests have come under attack in recent weeks. There have also been several incidents where tourists and foreign reporters were seized by vigilante mobs looking out for “spies” and who were subsequently taken to police stations or military checkpoints for investigation. While most of them were quickly freed, Ian Grapel — an Israeli-American law student remains in custody after being arrested in June on suspicion of being a Mossad agent sent by Israel to sow “unrest.”

Attacks on journalists covering the protests and the closure of several Islamist TV channels and a newspaper linked to the Muslim Brotherhood do not auger well for democracy and freedoms in the new Egypt. The current atmosphere is a far cry from the change aspired for by the opposition activists who had taken to Tahrir Square just weeks ago demanding the downfall of an Islamist regime they had complained was restricting civil liberties and freedom of speech.

The increased level of xenophobia and anti-US sentiment could damage relations with America and the EU at a time when the country is in need of support as it undergoes what the new interim government has promised would be a “successful democratic transition.”

Midia Ninja is a two-year-old media collective in Brazil that has risen to prominence for its reporting during mass demonstrations. (Photo: Midia Ninja)

Holding to their motto of “independent narratives, journalism and action”, a group of young journalists called Mídia Ninja (Ninja Media) used the recent demonstrations in Brazil’s major cities as a stage for their guerilla approach to journalism, using smartphones and social media platforms to reach their audience.

Mídia Ninja was formed two years ago as a hub for independent journalists in Brazil to tell stories with a social twist that traditional media was not covering. Until June this year, the group had 20 people working full time in six of Brazil’s major cities – São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Belo Horizonte, Porto Alegre and Fortaleza.

“We’re interested in showing the ‘B-side’ of things, exploring different narratives”, says Rafael Vilela, a Mídia Ninja member from São Paulo.

The group came to prominence in June, when they did onsite reporting and live streaming of the mass demonstrations in São Paulo and Rio against rising transport fares that evolved into a movement against the status quo. Being at the core of the action, they were able to shoot and broadcast on their Facebook page some of the most graphic videos of the clashes between protesters and the police.

Using smartphones and cameras, Mídia Ninja’s members mixed with the protesters, and ended up being targeted by the police as well. Three of them were arrested in Rio in July 22nd, during a demonstration against Governor Sergio Cabral.

This demonstration was the point where Mídia Ninja’s work drew the attention of mass audiences. Rede Globo, Brazil’s biggest TV network, showed the group’s interview with protester Bruno Ferreira Telles, who was arrested on the 22 July protest for allegedly throwing incendiary bombs against the police, and was charged with attempted murder.

In his interview, Bruno claimed he was innocent and urged Mídia Ninja to retrieve a video documenting he ran from the police with nothing in his hands – until then, police claimed he carried incendiary bombs when arrested. The video of barehanded Bruno being chased and detained was shown by Globo, and it helped his case. All charges against Bruno have been dropped.

Their work during the demonstrations raised Mídia Ninja’s profile in Brazil, especially through social media. The group’s Facebook page, which now is their main platform, grew from a little over 2,000 fans before June to more than 160,000, and their network of collaborators grew to more than 2,000 people.

“We’re still figuring out how to organize our collaborators work, because it’s so many people”, says Vilela.

The central core of Mídia Ninja is a group of one hundred people gathered in Brazil’s main urban areas. They have no salary: most of their expenses ares paid by Fora do Eixo (Out of the Axis), a network of cultural producers that began by financing independent music festivals in Brazil’s smaller urban areas, and ended up organizing bigger events related to film, music, visual arts and street art.

Most of Mídia Ninja’s members come out of journalism workshops created by Fora do Eixo, and some of them live at São Paulo’s Casa Fora do Eixo, a house where the network’s members can live and work as a community, sharing expenses.

After the street demonstrations became less massive, Mídia Ninja moved forward to cover other social issues like indigenous peoples’ rights. Their goal is to broaden their work.

“Since June we’ve been very focused on the demonstrations, but that’s not the only thing we want to do. There are many things to be written about – in culture, in sports, in daily life”, says Vilela.

Now Mídia Ninja’s main goal is to launch crowdfunding campaigns to support their activities – like launching a website, which is on the way.

Mídia Ninja is not free of criticism. One of their soft spots is precisely their closeness to Fora do Eixo. Many artists accuse Fora do Eixo and its coordinator Pablo Capilé of profiting at their expense, and also of exploiting young activists to work for the network for free.

Some media specialists even dispute if the work Mídia Ninja does should be seen as journalism, because of the way they become participants of the events they were supposed to report.

Digital Journalism professor Marcelo Träsel from PUCRS University in Porto Alegre, for example, says there seems to be a “promiscuous relation” between Mídia Ninja’s journalists and their objects.

“The fact that Mídia Ninja members were arrested alongside demonstrators shows that maybe they are exceeding their role of ‘eyewitness of facts’ that journalists so often claim.”

In the other hand, Träsel concedes that, for not playing the “impartiality card” that became common among big media, Mídia Ninja should be regarded differently than most outlets.

“It’s unfair to judge (Mídia Ninja’s) practices using the ethical code that operates in more traditional newsrooms. The question here is to know to which extent Mídia Ninja’s audience is conscious of the difference between their model and the one from big media, and to recognize the filters this audience uses when they get information from one and from the other”.