29 May 2014 | News, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

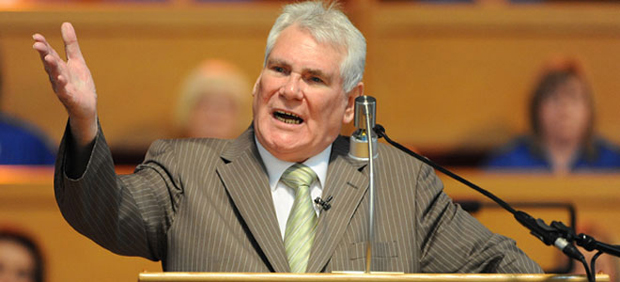

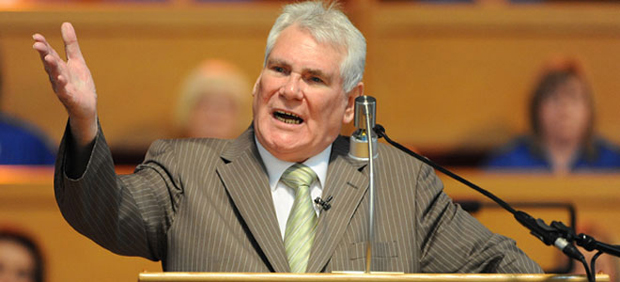

Pastor James McConnell

Belfast’s Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle is one of those things that makes a soft Southern Irish atheist Catholic like me think I’ll never truly understand Northern Ireland.

Every week, Ulster Christians flock from across the province to the 3,000-seater auditorium, there to hear Pastor James McConnell preach his Christian message. Not the Christian message of the BBC’s Thought For The Day, however; you may hear Beatitudes at Whitewell, but it’s not a place for platitudes. This is the real deal, fire and brimstone; damnation and salvation. If you’re not going to Whitewell, you’re going to Hell.

It is a comforting message, and actually, a very modern one. Think of how many politicians these days talk about how they work for hard-working-families-that-play-by-the-rules. Hardline evangelical Christianity is the epitome of that idea. We don’t refer to the “Protestant Work Ethic” for nothing.

But what we tend to forget when discussing hardliners from the outside is that there is a strong apocalyptic element in orthodox monotheistic religion. This is particularly true of Christianity. The closer to the core you get, the more you find Jesus’s teachings are essentially about the end of the world, not some vague being-nice-to-one-another schtick.

For some time, Christians have fretted over Matthew 24, in which Jesus apparently tells of the signs of his second coming, that is, to, say, the end of the world. What worries them particularly is Matthew 24:34: “Verily I say unto you, This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.”

Does this mean Jesus was telling his apostles that the world would end in their lifetime? CS Lewis, in his work The World’s Last Night, seemed to believe so, and went so far as to call the Messiah’s assertion “embarrassing”. Lewis wrote:

“‘Say what you like,’ we shall be told, ‘the apocalyptic beliefs of the first Christians have been proved to be false. It is clear from the New Testament that they all expected the Second Coming in their own lifetime. And, worse still, they had a reason, and one which you will find very embarrassing. Their Master had told them so. He shared, and indeed created, their delusion. He said in so many words, ‘This generation shall not pass till all these things be done.’ And he was wrong. He clearly knew no more about the end of the world than anyone else.”

“It is certainly the most embarrassing verse in the Bible. Yet how teasing, also, that within fourteen words of it should come the statement ‘But of that day and that hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father.’ The one exhibition of error and the one confession of ignorance grow side by side.”

Lewis, though himself a Northern Irish Protestant, was clearly not of the same cloth as Pastor McConnnell, Ian Paisley, and the other preachers of their ilk. Orwell disdained Lewis for his efforts to “persuade the suspicious reader, or listener, that one can be a Christian and a ‘jolly good chap’ at the same time.” The booming pastors of Northern Ireland, and other Christian strongholds such as the US’s Bible Belt, are very firmly convinced that the end is imminent. And thus, they do not have time to be “jolly nice chaps”. There are souls to be saved, right now.

It’s this attitude that has got Pastor McConnell into trouble in the past week. Recently, at Whitewell, inspired by the story of Meriam Yehya Ibrahim, a Sudanese woman reportedly sentenced to death for converting to Christianity, McConnell told the thousands assembled at his temple that “”Islam is heathen, Islam is Satanic, Islam is a doctrine spawned in Hell.”

In an interview with the BBC’s Stephen Nolan, McConnell refused to back down, claiming that all Muslims had a duty to impose Sharia law on the world, and suggesting they were all merely waiting for a signal to go to Holy War. A subtle examination of modern Islamist and jihadist politics this was not.

The PSNI is now investigating McConnell for hate speech. Northern Ireland’s politcians have been quick to comment. First Minister Peter Robinson backed McConnell, first saying that the preacher did not have an ounce of hate in his body, and then managing to make the situation worse by saying he would not trust Muslims on spiritual issues, but would trust a Muslim to “go down the shops for him”.

Insensitive and patronising that may be, but Robinson also touched on something more relevant to this publication when he said that Christian preachers had a responsibility to speak out on “false doctrines”.

The issue raised is this: if we genuinely believe something to be untrue, no matter how misguided we may be, do we not have a right to challenge it in robust terms? In politics we often bemoan the fact that leaders will not call things as they, or we, see them: indeed, Tony Blair, the bete noire of pretty much every political faction in Britain (a bete noire who oddly managed to win three election) has found grudging praise from across the spectrum this week for suggesting that rather than “listening to” or “understanding” the xenophobic United Kingdom Independence Party, politicians should tackle their arguments head on.

But in religion, we tend to hope that no one will upset anyone too much, in spite of the fact that, for true believers, theological issues are far more important than taxation or anything else.

When Blair’s government proposed (and eventually passed) a law against incitement to religious hatred in Britain, the opposition came from a coalition of secularists and some evangelical Christians, both groups realising, for different reasons, that being able to call an ideology false or untrue – and in the process criticise and question its adherents – was a fundamental right. The trade off in that is acknowledging others’ right to question your truths, something I suspect, judging by the recent controversy in Northern Ireland over a satirical revue based on the Bible, Pastor McConnell and his supporters may not quite excel at.

This article was originally posted on May 29, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 May 2014 | Lebanon, Middle East and North Africa, News

(Photo: Lucien Bourjeily/Twitter)

Lucien Bourjeily is smiling, and with good reason. Only two days earlier, the dark blue Lebanese passport he is holding up had been confiscated by the country’s intelligence agency, with no clear information of when he might get it back. The explanation given? “You know what you did.”

Speaking to Index on Censorship from Beirut, it’s clear that Bourjeily does know. This was not his first run-in with Lebanon’s General Security Directorate. The well-known writer saw his recent play about censorship in Lebanon banned by the agency, which counts media censorship among its many roles. His play was “unrealistic”, the censors told Bourjeily, the irony of the situation lost on them.

The experience earned him a nomination for this year’s Index awards. While he couldn’t attend the awards ceremony in London, he will be travelling to the UK in June to take part in the LIFT Festival with his latest production Vanishing State, which deals with redrawing borders in the Middle East. It was his attempt to renew his passport for this trip — another area under the jurisdiction of the directorate — that led to his latest ordeal.

Bourjeily is convinced the confiscation had been agreed on beforehand. Everyone he dealt with from the general security that day were saying the same thing, despite being in different rooms. “That’s how you know the decision had already been taken.”

A public figure in Lebanon, Bourjeily’s case drew huge media attention. People across the country rallied behind him, and lawyers offered to represent him for free. “I feel very lucky to have so much support, and that my case got so much favour in the public opinion,” he says.

He believes his latest case especially strikes a chord with his countrymen and women. “Every Lebanese loves their passport,” he says. “Freedom of movement for them is even more important than any other thing. Freedom of speech and now freedom of movement? This is too much!”

But he is not the only person to experience this. In 2010, general security confiscated the British passport of Nizar Saghieh, a dual British and Lebanese citizen. Prior to this, Saghieh had represented four Iraqis who were suing the Lebanese state over illegal detention by general security. He only got the passport back following direct intervention by then-Interior Minister Ziyad Baroud. Similarly, current Interior Minister Nouhad Machnouk stepped in on Bourjeily’s behalf, personally calling the director of the general security to demand the return of the passport.

He finally got it back on 23 May, with the message that the whole thing had been “a mistake”, and there would be an internal investigation. Bourjeily is not allowed to see the results of the investigation. He asked for justification on behalf of the Lebanese people, wondering whether the agency weren’t at least going to tell the public what they’d told him — that it had been a mistake. Again, he was told no.

Bourjeily says he will add this experience to the sequel of his banned play. He has also met with Saghieh, who heard about his case in the media, and they “discussed ways to collaborate together”. He has no doubt that this, all things considered, happy ending was down to public pressure. Others might not be as lucky.

“[What] if it [was] not me? If it’s not a person who has 30,000 followers on Facebook? If it was just any regular Joe in Lebanon? What would happen to them if they confiscated their passport?”

This article was posted on May 29 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 May 2014 | India, News, Politics and Society

Nitin Gadkari, a politician with a chequered, if not dubious record of integrity and probity, had a political opponent arrested for slander. (Photo: Amit Kumar/Demotix)

Once, President Lyndon Johnson was caught in the crossfire of an anti-Vietnam war protest. A placard was shoved in his face: “LBJ pull out, like your daddy should have done.” Sure, LBJ got the pun, as would have Anthony Weiner in our present times, but he remained unperturbed. Consider Lady Violet Bonham Carter’s biting repartee to an irresolute Sir Stafford Cripps, saying he “has a brilliant mind — until it is made up”.

Mordant wit is what makes politics and political debates sparkle with brilliance, besides deflating windbags and putting stuffed shirts in their place. Even if the “sourcasm” is discounted, plainspeak and no-holds barred verbal duels contribute in no small measure to ensuring accountability, for who isn’t mortally petrified of lacerating criticism?

Turns out that in India, folks with brittle egos and skeletons stacked up in their closets, can and will wield the law to clam a critic’s mouth shut, and even have them put in jail. And this is irrespective of resorting to some risqué puns.

Arvind Kejriwal, founder of the Aam Aadmi (Common Man) Party, who is out on a limb to eradicate the scourge of corruption, realised this to his peril when Nitin Gadkari, a politician with a chequered, if not dubious record of integrity and probity, had him arrested for slander. Slander? No, Gadkari wasn’t invoking some law of the Middle Ages or the Victorian Era. He was merely invoking Sections 499 and 500 of the Indian Penal Code which criminalise defamation, both in writing as well as verbal statements. Kejriwal called Gadkari “corrupt” because not very long ago, the latter did come under the scanner for alleged massive illegalities in his business dealings, but managed to wriggle out since no legal investigation or prosecution were launched.

These two provisions are so broad in scope that every insinuation, unless proved to have been made in “good faith”, can land someone in prison. Someone like Kejriwal, who was incarcerated for six days until he was let out on bail yesterday. Now how does one prove “good faith”, that too, “beyond reasonable doubt”, since that remains the standard of proof in criminal law? Worse, a person can be taken into custody even while this seemingly Herculean task is getting done.

As if criminalisation of libel isn’t bad enough, punishing “slander” grants almost instant impunity if one is strategic enough. Take Kejriwal’s example, again. In October and November last year, he addressed a press conference and read out from a list of charges against business tycoon Mukesh Ambani. The businessman lost no time in slapping legal notices against every television channel which broadcast the conference. Libel chill, without a shred of doubt, for all the channels went silent. Whether Ambani’s fleece is as white as snow isn’t the question; his dark deeds of pulverising criticism are, and deserve the most trenchant critique.

It is encouraging to note that already demands are being made for decriminalising libel, but unless slander is banished from the statute books, dangers would continue to lurk. The Law Commission of India has taken a laudatory and timely step by releasing a consultation paper which seeks to unshackle the media from apprehensions of libel chill. But what happens to individuals — political activists, or whistleblowers? A possible solution lies in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. wherein the Supreme Court of the United States extended the Sullivan privilege (named after the legendary NYT v. Sullivan case) — that only statements made with naked malice or reckless disregard for the truth shall be held as defamatory — available to media houses, to certain categories of individuals also. Those “seeking governmental office” and those who “occupy positions of such persuasive power and influence that they are deemed public figures for all purposes” were accorded protection. Recently, this has been adopted in international money laundering law of PEPs or Politically Exposed Persons. It includes, “individuals who are or have been entrusted domestically with prominent public functions, for example, heads of state or of government, senior politicians, senior government, judicial or military officials, senior executives of state-owned corporations, important political party officials”.

Back in 2011, the UNHRC (United Nations Human Rights Committee) issued a declaration condemning Philippines’ provisions of criminal libel as a violation of the ICCPR. One hopes India wouldn’t require such a slap on the wrists to amend the repugnant law which rewards dishonest claims of calumny.

This article was published on May 29, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

28 May 2014 | Digital Freedom, News, Politics and Society, United States

Last week saw a flurry of legislative to-and-fro on the Hill as the US House of Representatives pondered the passage of legislation aimed at ending bulk-collection by the US National Security Agency. The USA Freedom Act, or HR. 3361, was passed on Thursday in a 303-121 vote, and was hailed by The New York Times as “a rare moment of bipartisan agreement between the White House and Congress on a major national security issue”. Congressman Glenn ‘GT’ Thompson (R-Pa.) tweeted that he was the proud cosponsor of a bill “that passed uniting and strengthening America by ending eavesdropping/online monitoring.”

It was perhaps inevitable that compromise between the intelligence and judiciary committees would see various blows against the bill in terms of scope and effect. When legislators want to posture about change while asserting the status quo, ambiguity proves their steadfast friend. After all, with the term “freedom” in the bill, something was bound to give.

Students of the bill would have noted that its main author, Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wi.), was also behind HR. 3162, known more popularly as the USA Patriot Act. Most roads in the US surveillance establishment tend to lead to that roughly drafted and applied piece of legislation, a mechanism that gave the NSA the broadest, and most ineffective of mandates, in eavesdropping.

Then came salutatory remarks made about the bill from Rep. Mike Rogers[2], who extolled its virtues on the House floor even as he attacked the Obama administration for not being firm enough in holding against advocates of surveillance reform. There is a notable signature change between commending “a responsible legislative solution to address concerns about the bulk telephone metadata program” and being “held hostage by the actions of traitors who leak classified information that puts our troops in the field at risk or those who fear-monger and spread mistruth to further their misguided agenda.”

Even as Edward Snowden’s ghost hung heavy over the Hill like a moralising Banquo, Rogers was pointing a vengeful finger in his direction. There would, after all, have been no need for the USA Freedom Act, no need for this display of lawmaking, but for the actions of the intelligence sub-contractor. Privacy advocates would again raise their eyebrows at Rogers’s remarks about the now infamous Section 215 telephone metadata program under the Patriot Act, which had been “the subject of intense, and often inaccurate, criticism. The bulk telephone metadata program is legal, overseen, and effective at saving American lives.”

Such assertions are remarkable, more so for the fact that both the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board and the internal White House review panel, found little evidence of effectiveness in the program. “Section 215 of the USA Patriot Act,” claimed the PCLOB, “does not provide an adequate basis to support this program.” Any data obtained was thin and obtained at unwarranted cost.

Critics of the bill such as Centre for Democracy and Technology President Nuala O’Connor expressed concern at the chipping moves. “This legislation was designed to prohibit bulk collection, but has been made so weak that it fails to adequately protect against mass, untargeted collection of Americans’ private information.” In O’Connor’s view, “The bill now offers only mild reform and goes against the overwhelming support for definitively ending bulk collection.”

Not so, claimed an anonymous House GOP aide. “The amended bill successfully addresses the concerns that were raised about NSA surveillance, ends bulk collections and increases transparency.” Victory in small steps would seem to have impressed the aide. “We view it as a victory for privacy, and while we would like to have had a stronger bill, we shouldn’t let the perfect being the enemy of the good.”

Various members of the House disagreed. Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.) noted that the bill had received a severe pruning by the time it reached the House floor, having a change “that seems to open the door to bulk collection again.” Others connected with co-sponsoring initial versions of the bill, among them Rep. Jared Polis (D-Colo.) and Rep. Justin Amash (R-Mich.) also refused to vote for the compromise.

What, then, is the basis of the gripe? For one, the language “specific selection term”, which would cover what the NSA can intercept, is incorrigibly vague. The definition offers the unsatisfactory “term used to uniquely describe a person, entity or account.” What, in this sense, is an entity for the purpose of the legislation? The tip of the iceberg is already problematic enough without venturing down into the murkier depths of interpretation.

Even more troubling in the USA Freedom Act is what it leaves out. For one thing, telephony metadata is only a portion of the surveillance loot. Other collection programs are conspicuously absent, be it the already exposed PRISM program which covers online communications, Captivatedaudience, a program used to attain control of a computer’s microphone and record audio, Foggybottom – used to note a user’s browsing history on the net, and Gumfish, used to control a computer webcam. (These are the choice bits – others in the NSA arsenal persist, untrammelled.)

Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Amendments (FISA) Act, the provision outlining when the NSA may collect data from American citizens in various cases and how the incorrect or inadvertent collection of data is to be handled, is left untouched. On inspection, it seems the reformist resume of the Freedom Act is rather sparse.

Ambiguities, rather than perfections, end up being the enemy of the good. Laws that are poorly drafted tend to be more than mere nuisances – they can be dangerous in cultivating complacency before the effects of power. Well as it might that the USA Freedom Act has passed, signalling a political will to deal with bulk-collection of data. But in making that signal, Congress has also made it clear that compromise is one way of doing nothing, a form of sanctified inertia.

This article was posted on May 28, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org