30 May 2014 | Asia and Pacific, India, News and features

Gujarat Chief Minister and BJP prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi filed his nomination papers from Vadodara Lok Sabha seat amid tight security on April 6. (Photo: Nisarg Lakhmani/Demotix)

An Indian man has found himself in trouble for allegedly posting a Facebook comments against Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The incident raises serious doubts over online freedom in the world’s biggest democracy

On March 23, shipbuilding professional Devu Chodankar posted in the popular Facebook group Goa+, that if Modi became prime minister, a holocaust “as it happened in Gujarat”, would follow. Modi was the Gujarat chief minister during the 2002 pogrom in which more than 1000 people — most of them Muslims — were killed in communal violence. Chodankar also wrote that it would lead to the Christian community in the state of Goa losing their identity. He later deleted the post. In another Facebook group he regretted his choice of words but stood by the substance of his argument, calling it his crusade against the “tyranny of fascists”.

The incident was reported to the police in March by former chairman of the Confederation of Indian Industries in Goa Atul Pai Kane, who was close to Modi’s party Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). He filed a First Information Report (FIR) to the police, under sections 153(A), 295(A) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and section 125 of the People’s Representation Act and 66-A of the Information Technology Act. Under the former, it is a crime to promote enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc., as do acts prejudicial to maintenance of harmony. Meanwhile, the latter makes it a punishable offence to send messages that are offensive, false or created for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience.

In his complaint, Kane said that Chodankar had threatened the group members not to vote in favour of the BJP, as it would virtually make Narendra Modi the prime minister of India. “I made this complaint as Chodankar issued inflammatory statements and tried to create communal hatred. He even refused to withdraw those comments. You cannot make such comments on a public forum. There has to be a limit.”

Police summoned Chodankar for the first time on May 12, and a trial court on 22 May rejected anticipatory bail. Chodankar has left Goa to evade possible arrest. Police want to interrogate him to find out whether he had any broader intentions with his comments, and whether he had plans to “promote communal and social disharmony”.

Social activists and opposition political parties feel that lodging a police complaint over a Facebook comment is an attempt to curb individual freedom, and that such cases would become the order of the day under Hindu nationalist BJP rule. Activists also believe that this type of police action is tantamount to curbing freedom of expression, ultimately meaning that you should either stay away from social media or stop speaking your mind on such platforms.

Amitabh Pandey, a media freedom activist, said: “The message is very clear. You should know how to behave in the cyber world. If you dare to write against Narendra Modi on any social media platform then you should be ready to face the consequences.”

Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) alumnus Dr. Samir Kelekar has been actively working for the case against Chodankar to be dropped. “I feel arresting a person for making a comment against someone is too much. We don’t agree with his comments but we don’t agree with police action either. His comment is not going to affect the society in any way,” he said.

This isn’t the only such case in recent times in India. On 15 May, author Amaresh Mishra was arrested in Gurgaon, in the northern Indian state of Haryana, for posting content on Facebook and Twitter against Modi and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a radical Hindu organisation associated with BJP. Charges alleged he had incited violence against Modi.

Along with social activists, many netizens are opposing the police action against Chodankar. “In a way we are living in a country which claims that we have freedom of expression, but in reality it doesn’t exist,” said Facebook user Animesh Upadhyay, adding that people don’t know which comment will be treated as an offence and might get them arrested.

However, some feel that there has to be a limit. Ashutosh Jaiswal, convener of hardliner Hindu organisation Bajrang Dal said: “The police should deal sternly with such public comments.”

Goa Chief Minister Manohar Parrikar has refused to interfere in the case. In a written statement he said: “As per Supreme Court directives, it is compulsory to register all complaints. A prominent citizen has filed a complaint and judiciary has refused to grant anticipatory bail to the accused person, which proves that there is substance in the complaint.”

He has also stated that there was “no intention” to arrest Chodankar. “He was issued two summons after which he did not appear before police, and his lawyer went for anticipatory bail…Police opposed the bail as a regular process.”

This article was posted on May 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 May 2014 | News and features, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

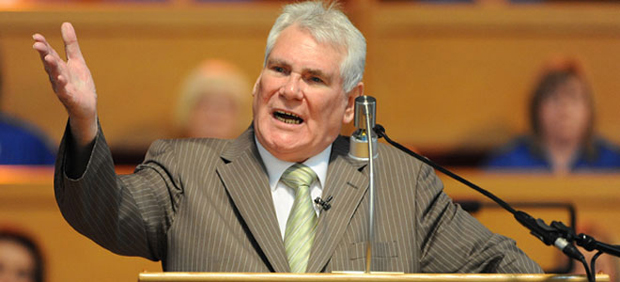

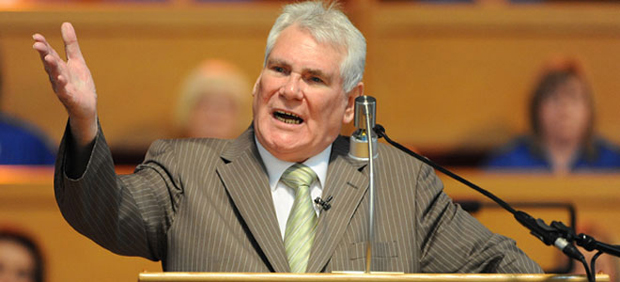

Pastor James McConnell

Belfast’s Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle is one of those things that makes a soft Southern Irish atheist Catholic like me think I’ll never truly understand Northern Ireland.

Every week, Ulster Christians flock from across the province to the 3,000-seater auditorium, there to hear Pastor James McConnell preach his Christian message. Not the Christian message of the BBC’s Thought For The Day, however; you may hear Beatitudes at Whitewell, but it’s not a place for platitudes. This is the real deal, fire and brimstone; damnation and salvation. If you’re not going to Whitewell, you’re going to Hell.

It is a comforting message, and actually, a very modern one. Think of how many politicians these days talk about how they work for hard-working-families-that-play-by-the-rules. Hardline evangelical Christianity is the epitome of that idea. We don’t refer to the “Protestant Work Ethic” for nothing.

But what we tend to forget when discussing hardliners from the outside is that there is a strong apocalyptic element in orthodox monotheistic religion. This is particularly true of Christianity. The closer to the core you get, the more you find Jesus’s teachings are essentially about the end of the world, not some vague being-nice-to-one-another schtick.

For some time, Christians have fretted over Matthew 24, in which Jesus apparently tells of the signs of his second coming, that is, to, say, the end of the world. What worries them particularly is Matthew 24:34: “Verily I say unto you, This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.”

Does this mean Jesus was telling his apostles that the world would end in their lifetime? CS Lewis, in his work The World’s Last Night, seemed to believe so, and went so far as to call the Messiah’s assertion “embarrassing”. Lewis wrote:

“‘Say what you like,’ we shall be told, ‘the apocalyptic beliefs of the first Christians have been proved to be false. It is clear from the New Testament that they all expected the Second Coming in their own lifetime. And, worse still, they had a reason, and one which you will find very embarrassing. Their Master had told them so. He shared, and indeed created, their delusion. He said in so many words, ‘This generation shall not pass till all these things be done.’ And he was wrong. He clearly knew no more about the end of the world than anyone else.”

“It is certainly the most embarrassing verse in the Bible. Yet how teasing, also, that within fourteen words of it should come the statement ‘But of that day and that hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father.’ The one exhibition of error and the one confession of ignorance grow side by side.”

Lewis, though himself a Northern Irish Protestant, was clearly not of the same cloth as Pastor McConnnell, Ian Paisley, and the other preachers of their ilk. Orwell disdained Lewis for his efforts to “persuade the suspicious reader, or listener, that one can be a Christian and a ‘jolly good chap’ at the same time.” The booming pastors of Northern Ireland, and other Christian strongholds such as the US’s Bible Belt, are very firmly convinced that the end is imminent. And thus, they do not have time to be “jolly nice chaps”. There are souls to be saved, right now.

It’s this attitude that has got Pastor McConnell into trouble in the past week. Recently, at Whitewell, inspired by the story of Meriam Yehya Ibrahim, a Sudanese woman reportedly sentenced to death for converting to Christianity, McConnell told the thousands assembled at his temple that “”Islam is heathen, Islam is Satanic, Islam is a doctrine spawned in Hell.”

In an interview with the BBC’s Stephen Nolan, McConnell refused to back down, claiming that all Muslims had a duty to impose Sharia law on the world, and suggesting they were all merely waiting for a signal to go to Holy War. A subtle examination of modern Islamist and jihadist politics this was not.

The PSNI is now investigating McConnell for hate speech. Northern Ireland’s politcians have been quick to comment. First Minister Peter Robinson backed McConnell, first saying that the preacher did not have an ounce of hate in his body, and then managing to make the situation worse by saying he would not trust Muslims on spiritual issues, but would trust a Muslim to “go down the shops for him”.

Insensitive and patronising that may be, but Robinson also touched on something more relevant to this publication when he said that Christian preachers had a responsibility to speak out on “false doctrines”.

The issue raised is this: if we genuinely believe something to be untrue, no matter how misguided we may be, do we not have a right to challenge it in robust terms? In politics we often bemoan the fact that leaders will not call things as they, or we, see them: indeed, Tony Blair, the bete noire of pretty much every political faction in Britain (a bete noire who oddly managed to win three election) has found grudging praise from across the spectrum this week for suggesting that rather than “listening to” or “understanding” the xenophobic United Kingdom Independence Party, politicians should tackle their arguments head on.

But in religion, we tend to hope that no one will upset anyone too much, in spite of the fact that, for true believers, theological issues are far more important than taxation or anything else.

When Blair’s government proposed (and eventually passed) a law against incitement to religious hatred in Britain, the opposition came from a coalition of secularists and some evangelical Christians, both groups realising, for different reasons, that being able to call an ideology false or untrue – and in the process criticise and question its adherents – was a fundamental right. The trade off in that is acknowledging others’ right to question your truths, something I suspect, judging by the recent controversy in Northern Ireland over a satirical revue based on the Bible, Pastor McConnell and his supporters may not quite excel at.

This article was originally posted on May 29, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 May 2014 | Lebanon, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

(Photo: Lucien Bourjeily/Twitter)

Lucien Bourjeily is smiling, and with good reason. Only two days earlier, the dark blue Lebanese passport he is holding up had been confiscated by the country’s intelligence agency, with no clear information of when he might get it back. The explanation given? “You know what you did.”

Speaking to Index on Censorship from Beirut, it’s clear that Bourjeily does know. This was not his first run-in with Lebanon’s General Security Directorate. The well-known writer saw his recent play about censorship in Lebanon banned by the agency, which counts media censorship among its many roles. His play was “unrealistic”, the censors told Bourjeily, the irony of the situation lost on them.

The experience earned him a nomination for this year’s Index awards. While he couldn’t attend the awards ceremony in London, he will be travelling to the UK in June to take part in the LIFT Festival with his latest production Vanishing State, which deals with redrawing borders in the Middle East. It was his attempt to renew his passport for this trip — another area under the jurisdiction of the directorate — that led to his latest ordeal.

Bourjeily is convinced the confiscation had been agreed on beforehand. Everyone he dealt with from the general security that day were saying the same thing, despite being in different rooms. “That’s how you know the decision had already been taken.”

A public figure in Lebanon, Bourjeily’s case drew huge media attention. People across the country rallied behind him, and lawyers offered to represent him for free. “I feel very lucky to have so much support, and that my case got so much favour in the public opinion,” he says.

He believes his latest case especially strikes a chord with his countrymen and women. “Every Lebanese loves their passport,” he says. “Freedom of movement for them is even more important than any other thing. Freedom of speech and now freedom of movement? This is too much!”

But he is not the only person to experience this. In 2010, general security confiscated the British passport of Nizar Saghieh, a dual British and Lebanese citizen. Prior to this, Saghieh had represented four Iraqis who were suing the Lebanese state over illegal detention by general security. He only got the passport back following direct intervention by then-Interior Minister Ziyad Baroud. Similarly, current Interior Minister Nouhad Machnouk stepped in on Bourjeily’s behalf, personally calling the director of the general security to demand the return of the passport.

He finally got it back on 23 May, with the message that the whole thing had been “a mistake”, and there would be an internal investigation. Bourjeily is not allowed to see the results of the investigation. He asked for justification on behalf of the Lebanese people, wondering whether the agency weren’t at least going to tell the public what they’d told him — that it had been a mistake. Again, he was told no.

Bourjeily says he will add this experience to the sequel of his banned play. He has also met with Saghieh, who heard about his case in the media, and they “discussed ways to collaborate together”. He has no doubt that this, all things considered, happy ending was down to public pressure. Others might not be as lucky.

“[What] if it [was] not me? If it’s not a person who has 30,000 followers on Facebook? If it was just any regular Joe in Lebanon? What would happen to them if they confiscated their passport?”

This article was posted on May 29 2014 at indexoncensorship.org