4 Mar 2014 | Americas, Awards, News, United States

Glenn Greenwald had previously blogged on surveillance and civil liberties for Salon and the Guardian, attracting thousands of followers with his dogged writing. Laura Poitras’s background is in documentary making, having made highly acclaimed films about Iraqis living during the US military occupation and The Oath, a film about Yemenis caught up in the War on Terror.

A lawyer by training, Greenwald built a strong reputation for detailed, forensic articles. According to the Guardian, an article by Greenwald about Poitras’s work and fears over targeting by the government was what convinced Edward Snowden to approach him with his cache of NSA files in late 2012.

Working with a range of outlets, from the Guardian to Brazil’s O Globo, Greenwald published a range of stories on the workings of the National Security Agency’s surveillance. Germany-based Poitras collaborated with Der Spiegel amongst others, generating huge debate in that country.

In August 2013, Greenwald’s partner David Miranda was detained at Heathrow Airport under terrorism legislation and had documents he had received from Poitras confiscated by UK authorities.

Interviewed by Esquire magazine, Greenwald explained why he felt it was important to uncover mass surveillance: “ultimately the reason privacy is so vital is it’s the realm in which we can do all the things that are valuable as human beings. It’s the place that uniquely enables us to explore limits, to test boundaries, to engage in novel and creative ways of thinking and being”

Nominees: Advocacy | Arts | Digital Activism | Journalism

Join us 20 March 2014 at the Barbican Centre for the Freedom of Expression Awards

This article was posted on March 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

4 Mar 2014 | Africa, News, Uganda

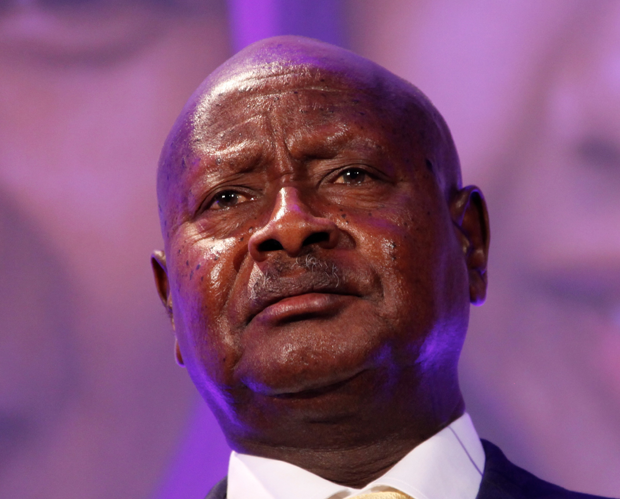

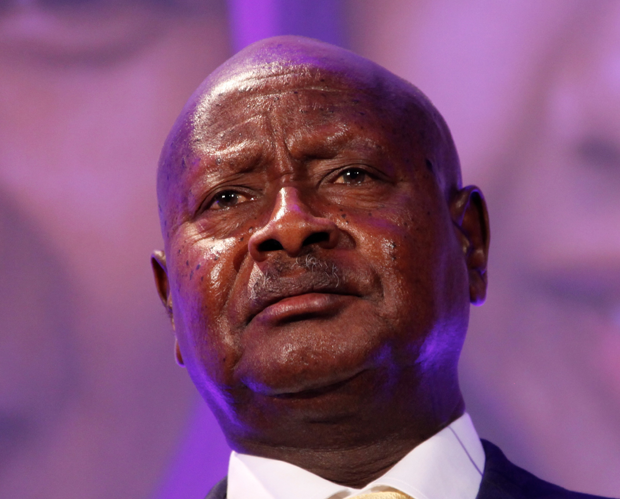

Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni (Photo: Wikipedia)

President Yoweri Museveni signed Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality bill into law on 24 February, and the fallout has already started. The World Bank has cancelled a $90 million loan to the country, European Union countries are threatening to withdraw aid, and the United States is reviewing its cooperation with Uganda. President Museveni has hit back, saying Uganda would raise its own money to fund its development projects. The US, which was the first voice its discontent, was told off: “Our relationship with the US was not based on homosexuality.” David Bahati, the MP who introduced the bill, said in an interview that the west is imposing social imperialism on Uganda, a thing they are not ready to accept.

“I will work with the Russians,” Museveni said.

So the president feels that even without the west, Uganda has development partners that it can still rely on. Considering he was not supportive of the so-called Bahati bill in its initial stages, Museveni’s last-minute change of heart is baffling.

The law stipulates that punishment for homosexuals will be a life jail sentence, while those who “attempt” to engage in homosexual acts face seven years in prison. The law also targets journalists and others seen to participate in “production, procuring, marketing, broadcasting, disseminating, publishing of pornographic materials for purposes of promoting homosexuality”. It even attempts to reach beyond the country’s borders, implong that Uganda will have to ask countries where gay Ugandans live to extradite them so that they can face the law.

Public opinion goes both ways. Many are happy that the president is standing firm against “the west” and the perceived scheme of promoting homosexuality in Uganda and Africa at large. Others claim that the president signed this law to achieve cheap popularity with the 2016 elections around the corner. It is also claimed that President Museveni is just playing his usual political games. When the anti-homosexuality bill was passed by parliament early this year, one of the president’s legal brains, Fox Odoi, publicly stated that if the president ever assents to this law, he would challenge it in court.

Odoi has now teamed up with Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda to take the case to the constitutional court. It is alleged that this was Museveni’s game plan: sign the law, annoy the west and appease the locals, and then have his henchmen challenge this law in court and make sure it remains there forever. In this case, the west will soften their stance towards Museveni, and the locals will be told to be patient and leave the legal process to take its course. In that case, he will have killed two birds with one stone, and would go for the 2016 elections with both the west and the locals in his pockets.

Civil society has also been critical, not because the anti-homosexuality law is unnecessary per se, but they have questioned whether homosexuality is the biggest problem Uganda faces today, and warrants such urgency. With high youth unemployment, squalid conditions in health facilities and theft of public funds in government institutions, they believe priorities should lie somewhere else other than “fixing” homosexuality.

“The timing for the assenting to this law by the president is meant to divert the country’s attention from the discussion on the deployment of Ugandan forces in South Sudan and our mandate there. This law is very diversionary, and it is unfortunate that Ugandans have swallowed the president’s bait,” said Godber Tumushabe, a renowned civil society activist.

Opposition leader Kizza Besigye has criticised the new law, saying that homosexuality was not “foreign” and that the issue was being used to divert attention from domestic problems. “Homosexuality is as Ugandan as any other behaviour, it has nothing to do with the foreigners,” said Besigye. He accused the government of having “ulterior motives” and using the issue to divert attention from other issues, including Uganda’s military backing of neighbouring South Sudan’s government against rebel forces.

Sweden’s Finance Minister Anders Borg, who visited the country a day after the signing of the law, said it “presents an economic risk for Uganda”.

But Besigye accused them of double standards, saying that their cutting of aid over gay rights alone was “misguided”:

”They should have cut aid a long time ago because of more fundamental rights, our rights have been violated with impunity and they kept silent,” he said.

This article was posted on March 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Mar 2014 | Iran, Middle East and North Africa, News

(Image: Meysam Mim/Demotix)

It has been six months since Hassan Rouhani took office as the 7th president of Iran’s Islamic government. Considering his government a moderate one, in the first weeks of his tenure, as he introduced his cabinet members, the cultural industry hoped for conditions to take a turn for the better after 8 years of suppression brought about by former president Ahmadinejad and the hardliners. Although the situation seems to be neither dramatically better nor worse, Rouhani is sending mixed messages on artistic freedom.

There have been positive steps, like in September 2013 the government reopened Iran’s House of Cinema. The former government had announced this non-governmental organisation was considered an illegal entity and dissolved it two years previously. The new Ministry of Culture announced that it had been shut down by the previous government but never dissolved, “as a registered organisation has an legal identity and cannot be dissolved by the Ministry”. Many celebrated and veteran filmmakers, even those who boycotted cinema during Ahmadinejad’s time, attended the ceremony of reopening the House of Cinema to show their support for new policies towards more freedom for artists.

There was also some good news for the literary community. Cheshmeh, a major publishing house, got its licence back in January 2014. Ahmadinejad government had revoked it in June 2012 for being “insulting to Imam Hossein, the third Imam of Shiites”. Before this accusations Cheshmeh had received several notices to stop “promoting western ideas”.

Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance Ali Jannati, was early drawn into the spotlight, participating in press conferences about his policies on books and films. Jannati announced he would move towards removing the procedures of pre-publication licensing of books, which has sparked both new hopes and new concerns. Iranian authors saw this as a good opportunity to send their old books to publishers, but publishers were concerned that publishing books which have no guarantee of being approved, could be an expensive exercise amid paper price increases.

However, Jannati later stated that the Islamic Republic of Iran has principles that need to be upheld, and while they would need to maintain the current review and permission process, they may be able to accelerate the process. The first action of the new minister was to return books that had been in the hands of the auditing committee for an extended period of time. This did not mean that the books had been accepted, and the list of required amendments handed back to publishers and authors demonstrated that the government’s approach and attitude, at least as of yet, has not changed.

Rouhani and Ali Jannati both had meetings in the past six months with Iranian artists in both publishing and cinema, promising to pursue positive changes to facilitate the licensing procedures for books and making movies. Ali Jannati also said that artists need a secure space rather than a space controlled by security forces to be able to function. Rouhani said that art can not be commissioned or controlled. They both insist that controlling cultural industry is not the government responsibility and they suggest it would be better to shift the controlling system to the artists themselves.

Specifically regarding books, they’ve said the publishers should take the responsibility for the scrutiny of books, which diverts attention away from the government. This could pose a great danger to the publishing industry, with an increased risk that publishers could take a stricter approach to censorship than the government because they have more to lose. In a gathering with cinema industry practitioners in early January, Hassan Rouhani mentioned that now is the time to stop making sad and dark movies and encouraged movie makers to instead make hopeful and optimistic works. This seemed an official order rather than an inspiration.

The Iranian Writers Association has not been officially allowed to work or organise any gathering and event for over 15 years. In an recent interview, the cultural deputy of the Ministry of Cultural and Islamic guidance said, on the topic of the writers association resuming its activities: “Some members are dead and the rest are not into working anymore. So the Association can shed skin which is for the benefit of the Association and other writers.”

Shed skin means that the troublemakers in the eyes of the government — writers working against suppression and censorship — must leave so others could stay. The response of Writers Association was simple and clear: “If shedding skin means don’t say and don’t write, it is never possible.”

This article was posted on March 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Mar 2014 | Gambia, News

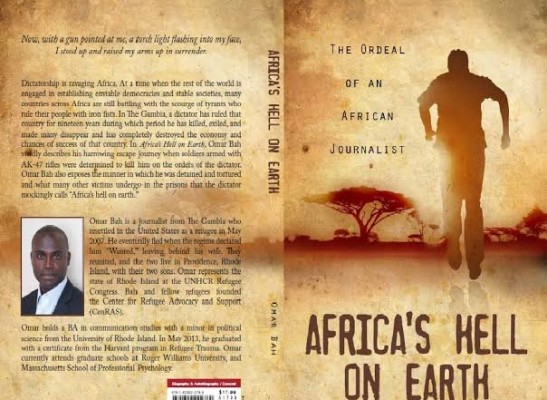

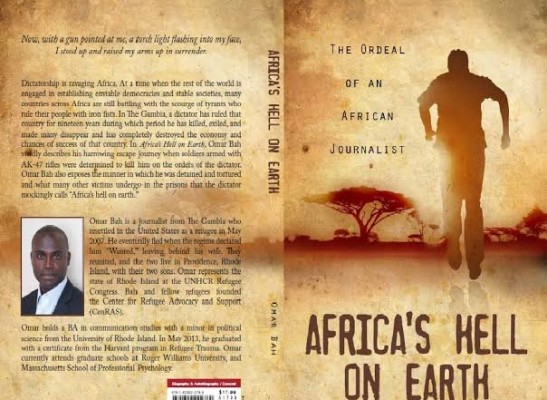

Driven into exile by the brutal regime of Gambia’s president, Yahya Jammeh, journalist Omar Bah’s dramatic flight from his homeland is recounted in his memoir Africa’s Hell on Earth: The Ordeal of an African Journalist.

An outspoken critic of the country’s autocratic ruler, Bah was forced to flee Gambia for neighbouring Senegal, where he was welcomed by other Gambian exiles who had settled in Dakar. Later, his path led him to Ghana and eventual resettlement in the US.

“I wanted to use my new found freedom in America to speak up because I regained the voice I lost. The book is my source of rejuvenation, my symbol of refusal to be silenced, and the avenue to continue to expose corruption, mismanagement, torture, repression, killings and the general dictatorship in The Gambia. I feel I owe it to the suffering people in The Gambia”, he stated.

Bah fell from grace after he was suspected of the being an informant for US-based Freedom, an online news site critical of the Jammeh regime, while working for the pro-government Daily Observer newspaper.

As a US resident, Bah says he feels challenged to speak about the injustices and give a voice to the voiceless since he now has the ability to speak up against the dictatorship in the Gambia without fear of reprisal.

“The name of this book, Africa’s Hell on Earth, refers to the nickname of the infamous Gambian prisons where so many people have disappeared. The prisons are overcrowded, and there are lots of diseases, torture, executions and suffering. Worse still, majority of the detainees are there simply because they oppose the regime. The Gambian dictator, Yahya Jammeh, has ruled for nineteen years. During this period, he has killed, tortured and exiled many Gambians.”

He said the Gambia is a country where is so much poverty while the powers that be live in luxury without regard to the poor and sick population. The writer bemoaned the situation of the Gambian people, who are subjected to summary executions if they dare oppose the regime.

In a review of Bah’s book Demba Ali Jawo, a former president of the Gambia Press Union, described it as an accurate depiction of the obstacles Gambian journalists have faced since the Jammeh regime came to power. Jawo called the book an invaluable reference for those interested in documenting the atrocities being committed against innocent Gambians by their own government.

According to Jawo, Bah narrowly escaped a dragnet that had been thrown around the Gambian capital, Banjul, to arrest him. A soldier let Bah pass through a checkpoint.

“By letting Omar go, the soldier not only risked his own job and life, but he also had to forego promotion and even compensation if he had handed him over to the authorities”, Jawo observed.

Bah now lives in Rode Island with his wife and two sons is attending graduate school through scholarship. He is the founder of the Center for Refugee Advocacy and Support and represents the state of Rode Island and the Northeast region at the Washington-based UNHCR Refugee Congress.

“When I look back at my journey, I feel my struggle was worth it. Despite the danger I had put myself in, and all that I went through, the nation of the United States of America, out of all the countries in the world, gave me the opportunity to begin a second life. Today, I feel my new life in America, though just starting, has been dearly meaningful. I am thankful to this country.”

He advised fellow refugees and immigrants make use of the opportunities that they have in the US and remember that there are millions who remain in the camps with no hope of rebuilding their lives.

This article was published on March 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org