17 Jun 2014 | News, Volume 43.02 Summer 2014

Former President of Poland Lech Walesa talks to the media at the Fallen Shipyard Workers Monument in Gdansk. (Photo: Michal Fludra/Alamy)

Poland had the largest alternative press on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain – and journalists couldn’t wait for the arrival of democracy. But after its heyday in the early 90s, the Polish media have lost their willingness to take on the powerful, argues Konstanty Gebert, who has kept a printing press, just in case. This an abridged version of an article from the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine – an “after the wall” special. For more, subscribe here

Twenty five years ago, as the round-table talks in Warsaw between the communist government and the opposition moved forward in the transition to democracy, the courtyard of Warsaw university became a print-lovers’ paradise. All kinds of underground publications, from books to newspapers, previously distributed only under the cover of secrecy, circulated in the open, provoking delight, outrage, concern and shock from passers-by. Watching vendors hawking my own publication, the fortnightly KOS, I grappled with the idea that we might actually become a normal newspaper, sold at newsstands and not in trusted private apartments, competing for newsprint, stories and readers in a free market of commodities and ideas. My only concern was that the promise of liberty would again prove a false dawn. I decided that, if we were to go “overground”, we should stash all our printing equipment and supplies somewhere, ready to pick up our clandestine work again if the political situation soured. This, to my eyes, was the greatest threat. Little did I know.

The alternative press had been both the backbone of the underground and one of its most distinctive features: no other communist country had an output that matched Poland’s. The Polish National Library has collected almost 6,000 different titles for the years 1976 to 1989 and the estimated number of readers is assessed at anything from 250,000 upwards. In 1987, KOS published a circular, issued by the regional prosecutor in the provincial industrial town of Płock. It informed his staff that if, during a house search (in a routine criminal investigation, not a political case), no underground publications were found, they needed to assume the inhabitants had been forewarned and had the time to clean up. In other words, the communist state assumed that the absence, not the presence, of underground publications in a typical Polish household was an anomaly that demanded an explanation.

This meant that, when the transition initiated by the round-table talks rushed forward at an unexpectedly speedy pace, we actually had trained journalists ready to take over hitherto state-controlled publications and, more importantly, set up new ones from scratch. The daily Gazeta Wyborcza (the Electoral Gazette was set up to promote Solidarity candidates in the first, semi-free elections of June 1989, but continued beyond that), which proudly advertised itself as the first free newspaper between the Elbe and Vladivostok, became an instant hit. Many formerly underground journalists, including myself, joined the paper, making it, for a while, a collective successor of the entire underground press. Its print run, initially limited by state newsprint allocations to 150,000 copies, soared to 500,000 once the remains of the communist state had been dismantled, and then dropped to under 300,000, as print media lost readers.

The newspaper’s unparalleled success (also financial: its publisher Agora went public in 1999 and shares initially did well) was due both to the extraordinary importance attributed under communism to the printed word and to the belief that the paper expressed “the truth” as opposed to “the lie” of the communist media. Under the government’s tightly controlled system of public expression (everything, down to matchbox labels, had to clear censorship), reality was defined by what was written, not by what was witnessed.

The underground press described a reality totally at odds with the image presented in the official media, yet validated by everyday experience: it was therefore “true”, and this exposed the communists as liars, who, moreover, were powerless to do anything about being exposed, since underground media continued to flourish, police repression notwithstanding. At the same time, the underground press was if not a propaganda venture at least an advocacy one, devoted not to the objective and non-partisan discussion of reality but to the promotion of a political current: the anti-communist opposition. Then we saw no contradiction in considering ourselves independent while supporting Solidarity candidates.

This contradiction was to explode shortly after. In 1990, barely a year after the transformation began, the first democratic presidential elections pitted Solidarity leader Lech Wałesa against his more politically liberal former chief adviser and first non-communist prime minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki. The unity of the anti-communist movement did not survive the defeat of its adversary – and rightly so. Gazeta Wyborcza endorsed Mazowiecki, to the outrage of many of its readers, even if they, too, voted mainly for the former PM. “Your job,” one reader wrote, “is not to tell me how to vote. Your job is to give me information so I can make up my mind myself.” The newspaper could no longer count on the uncritical trust of its readers, yet it kept the position of market leader, a rarity for a quality newspaper, until it was dethroned in 2003 by tabloid Fakt.

Gazeta Wyborcza has also become the most reviled paper, at least to its adversaries in the right-wing press. The Wałesa-Mazowiecki split exposed a deep structural fissure inside the anti-communist camp, between the conservative-nationalist Catholics, who endorsed the eventual winner, and the liberal-cosmopolitan secularists, who supported the former PM. As this fissure grew (deep internal divisions within both camps notwithstanding, and regardless of their shared hostility to the former communists), Gazeta Wyborcza became, in the eyes of the right, the embodiment of an alleged “anti-Polish” project – the fact that editor- in-chief and former political prisoner Adam Michnik is Jewish was sometimes proof enough – that had to be destroyed at all costs. The declining fortunes of the newspaper in recent years have been taken by the right as proof that Poland is now “finally becoming truly independent”.

An unexpected challenge came from the former spokesman of the communist government, Jerzy Urban, who in 1990 launched his weekly publication Nie (“no” in Polish). As Urban had been easily the most hated man in Poland, his enterprise was considered doomed in advance by most – and yet Nie proved vastly successful, claiming print runs of 300,000 to 600,000 (no independent audit was available, but these estimates are credible). The weekly publication – a mixture of Private Eye-style satire, hard porn, vulgar language and excellent investigative reporting – became an instant hit, because it concentrated on a major area neglected in the anti-communist media: the anti-communists themselves. Gazeta Wyborcza and other new or restructured media had been derelict in their duty of investigating their friends in power with the same determination and mis-trust we had previously applied against the communist authorities. This was true of our coverage not only of government, but also of the Catholic church. Remembered as a victim of communist persecution and as an ally and protector of the underground (even if the reality had been more complex), trusted and revered by the overwhelming majority of the nation, the church was really beyond public criticism. Urban rightly saw in that a potential killing.

And he went after anti-communist ministers and Catholic bishops with a vengeance that struck a chord, not only among the (substantial) former-communist readership, but also among many ordinary readers, who saw in the new authorities more of a continuation of the powers-that-be of old than we would care to admit. Even if uniformly vulgar and occasionally misinformed, his criticisms were painful and to the point. The mainstream media eventually caught up, investigating the secular and ecclesiastical authorities as they should, and, eventually, pushed Urban into a niche of spiteful readers, who appreciate his vulgarity more than his incisiveness; his weekly has a current print run of around 75,000. But it took the twin lessons of the internal political split in Solidarity and the unexpected success of a seemingly compromised propagandist to force mainstream media to understand the basic obligations of their job.

In broadcasting, changes were less dramatic, as there were no trained cadre of independent radio or TV journalists to replace the old hacks: there were hardly any underground broadcast media. More importantly, the new governments, left and right, proved just as reluctant as their predecessors to give up on controlling TV, in the unfounded belief that this helps one win elections. In fact, only one government has been re-elected in the past 25 years, even though all have had as much control over state TV as they wanted and private TV has generally been politically timid. Pressure on radio was much less obvious, and private radio stations have flourished. The most successful one is perhaps Radio Maryja, a Catholic fundamentalist broadcaster, sharply critical of democracy and European integration, and long accused of producing anti-semitic content. From being the object of criticism of the church establishment for its independently extremist line, it has become its de facto mouthpiece: it can get dozens of people out on the street and get MPs elected.

Overall, however, the underground era and the first few years after 1989 were probably the heyday of Polish journalism. But from a high point of newspapers being the visible incarnation of collective political triumph, we have come to a situation when readers read little, trust even less, and believe that media have mainly entertainment value at best, and represent a hostile power run amuck at worst. New media, though immensely popular due to high internet access (53.5 per cent), still run into the problems of bias and low credibility. The printing equipment I had stashed away a quarter-century ago still gathers dust in a Warsaw cellar, its technology as remote from today’s electronic potential as the medium it produced is from today’s media.

Konstanty Gebert is a Polish journalist. He has worked at Gazeta Wyborcza since 1992 and is the founder of Jewish magazine Midrasz. He was a leading Solidarity journalist, and co-founder of the Jewish Flying University in 1979.

This article appears in the summer 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Get your copy of the issue by subscribing here or downloading the iPad app.

17 Jun 2014 | Brazil, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, News

This is the fourth and final in a series of articles based on the Index report: Brazil: A new global internet referee?

With the adoption of a progressive legislation on internet rights, Brazil is taking the lead in digital freedom. Digital technologies have provided new opportunities for freedom of expression in the country, but have also come with new attempts to regulate content and strong inequalities between those with and without access to the internet. Old problems like violence against journalists, media concentration and the influence of local political leaders over judges and other public agents persist.

As internet penetration and access to the internet via mobile phone is increasing in the country, it is interesting to see how digital inclusion has created a new space for the exchange of ideas and reshaped the wider debate on freedom of expression. The emergence of independent media such as the collective Midia Ninja demonstrates the impact of digital on the offline free speech environment.

Brazil must now build on Marco Civil to ensure the respect of the right to freedom of expression online and offline, and promote internet rights in the international sphere.

In order for Brazil to provide a safe space for digital freedom and ensure the promise of Marco Civil is met in reality, Index on Censorship offers the following recommendations:

At the international level, Brazil should:

- Use its leadership to further promote a free and fair internet by continuing to publicly advocate for fundamental internet principles such as net neutrality, user privacy and freedom of expression in international forums

- Ensure that civil society organisations are deeply involved in the discussions and decision-making process on global internet governance, and that the outcome of international debates adequately reflect their recommendations

- Resist intervention by powerful lobby groups and governments to skew the outcome of multistakeholder gatherings

- Refuse to adopt or sign up to repressive measures and/or international agreements favouring internet censorship, top-down approach of internet governance and tighter government control of the internet

At the domestic level, Brazil should:

- Reform defamation and privacy laws to ensure they are not used to prosecute journalists and citizens who express legitimate opinions in online debates, posts and discussions

- Provide proper training to the judiciary and law enforcement agencies on defamation and other freedom of expression-related issues

- Introduce clear guidelines regarding civil defamation lawsuits, especially in regard to the use of content takedown and the setting of indemnification amounts

- Ensure that all cases of killings and other forms of violence against media professionals and human rights defenders are effectively, promptly and independently investigated, and those responsible are held accountable

- Be more transparent about the ongoing work around privacy legislation, including the Data Protection Bill

- Pursue their efforts in promoting digital access and inclusion to all Brazilians by expanding the Digital Cities programme and stick to the target of ensuring 40 million households or 68% of the population are able to access broadband by the end of 2014 as part of the National Broadband Plan

The full report is available in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]

Part 1 Towards an internet “bill of rights” | Part 2 Digital access and inclusion | Part 3 Brazil taking the lead in international debates about internet governance | Part 4 Conclusions and recommendations

This article was posted on 16 June 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Jun 2014 | Brazil, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, News

This is the third in a series of articles based on the Index report: Brazil: A new global internet referee?

Key debates are under way at international level on internet governance, with crucial decisions up for grabs that could determine whether the internet remains a broadly free and open space, with a bottom up approach to its operation – as exemplified in part by the multistakeholder approach – or becomes a top-down controlled space as pushed for by China and Russia, supported to some extent by several other countries.

In September 2013, the outrage following the revelations of mass surveillance by the US and UK led President Dilma Rousseff to announce that Brazil would host an international summit – NETmundial – on the future of internet governance in April 2014. This internet governance summit – progressive in appearance – took place just two years after Brazil voted in line with countries that have a tradition of internet control at a major international conference on telecommunications in Dubai.

This section looks at Brazil’s attitude in global internet governance debates and the potential contradictions between its domestic and foreign internet policies. In the aftermath of NETmundial and a year before Brazil is to host the 2015 Internet Governance Forum (IGF), this chapter also looks at Brazil’s ability to impose itself as a world leader in internet governance debates.

Is Brazil a swing state on global internet governance? Contradictions between domestic and international policies

What is at stake during the international discussions that shape the evolution and use of the internet has implications for all. The current multistakeholder approach for internet governance supposedly includes civil society and non-governmental actors in decision-making. It is a more bottom-up and multi-layered process, allowing a range of organisations to determine or contribute towards different parts of internet governance. The consultation process at the origin of the Marco Civil law is a possible example of the multistakeholder approach in action: Civil society, private companies, academics, law enforcement officials and politicians participated in the draft.

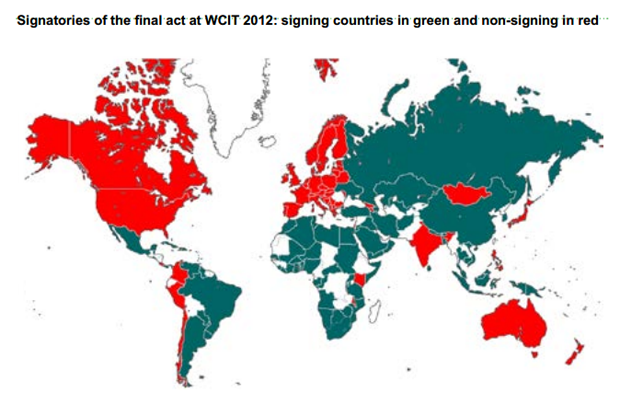

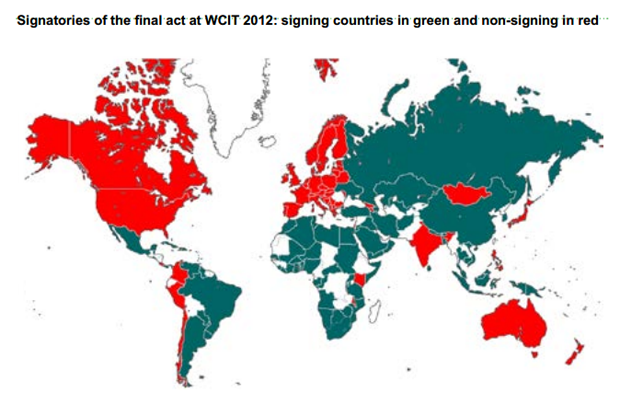

While Brazil has been pushing for stronger internet freedoms lately, especially at the domestic level, it has a history of going in the other direction. In December 2012, Brazil aligned with a top-down approach lobbied by countries that have a tradition of internet control at the Dubai World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT) summit. This meeting brought together 193 member states of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in part to decide whether or not and how the ITU should regulate the internet. On one side, EU member states and the US argued the internet should remain governed by an open and collaborative multistakeholder approach. On the other side of the divide, Russia, China and Iran lobbied for greater government control of the net. Brazil, along with the most influential emerging democratic powers (India the notable exception), aligned with this top-down approach.

This decision appeared in total contradiction with Brazil’s defence and implementation of the multistakeholder model at home with Marco Civil (see previous section on Marco Civil da Internet). At the time, the rapporteur of Marco Civil, Alessandro Molon, was opposed to the new ITU regulations and regretted that Marco Civil had not been adopted before the vote. While it is not unusual for any government to see a contradiction between domestic and foreign policy, Molon believed that the adoption of Marco Civil would have established without doubt Brazil’s policy and support for a transparent and inclusive approach to internet governance.

The reasons behind Brazil’s vote at the WCIT are obscure. First of all it is worth noting that most Latin American countries voted in favour of the text adopting new International Telecommunications Regulations. An analysis of the region’s vote shows that beyond governments’ intentions and goodwill towards the current multistakeholder governance model, to most Latin American governments, the new regulations were not about the internet but about telecommunications. Most of these governments would have looked at the new ITRs to “reap some of the benefits of the ITRs as a whole”, especially in terms of technical facilities. Second, like India, Brazil has increasingly expressed its desire to take on the US hegemony over the internet and digital technologies. The clash between the two sides revealed at WCIT 2012 led The Economist to call WCIT 2012 a “digital cold war”. Brazil’s position is, however, more complex. Neither a supporter of the US nor Sino-Russian initiatives, Brazil has been seeking greater recognition in multilateral forums and has called for the rebalancing of international institutions. As one of the new global economic powerhouses alongside Russia, India and China, but considered the most democratic of that group with India, aligning with countries supporting tighter government control was more a statement against internet governance by institutions seen as under US control – namely ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) – and an assertion of Brazil’s sovereignty.

The revelations on mass surveillance activities carried out by the US further fuelled Brazil’s will to break from US-centric internet. Standing against mass surveillance, Brazil distanced itself from the top-down internet governance approach and called for an “open, multilateral and democratic governance, carried out with transparency by stimulating collective creativity and the participation of society, governments and the private sector.”

Shortly after announcing the organisation of an international conference to discuss the future of internet governance in response to the surveillance revelations, President Dilma Rousseff also ordered a series of measures aimed at greater Brazilian online independence and security. But what are the internet governance implications of that opposition to the US spying? By trying to get away from the US dominance of the internet, Roussef’s measures risk taking a regressive stance on the internet. Paradoxically, while asserting internet freedoms, the geopolitics behind Brazil’s response to mass surveillance could align it with countries pushing for top-down internet control both nationally and internationally.

After Snowden: Brazil taking the lead and opposing mass surveillance – but at what cost?

In September 2013, President Dilma Rousseff made a strong political response to Snowden’s revelations on mass surveillance activities carried out by the United States. In a speech delivered to the UN General Assembly, Brazil’s president accused the NSA of violating international law and called on the UN to oversee a new legal system to govern the internet. Rousseff seized the momentum created by Snowden’s revelations to question the current multilateral mechanisms in place – such as ICANN – and announced that Brazil would host an international summit to discuss the future of internet governance in April 2014: NETmundial. ICANN has faced growing criticism in recent years about the influence of the US government on its operations. In this context, the efforts of Brazil in promoting digital freedom at domestic level with Marco Civil have helped the country gain a leading role and visibility in internet rights discussions. While India used to appear as a natural leader of the debate, discussions on Marco Civil and internet legislation have reached an international audience to the extent that Indian politicians now say “India has lost its leadership status to Brazil in the internet governance space”.

Not only is Brazil one of the countries with emerging influence in the multipolar world but it is also a state whose population is increasingly engaging with the internet. The decision to host NETmundial shows both Brazil’s stand against mass surveillance – at least officially – and its ambition to take the lead on internet governance debates.

The opposition to US-led mass surveillance led Brazil to propose a series of ambitious and controversial measures aimed at extricating the internet in Brazil from the influence of the US and its tech giants, in particular protecting Brazilians from the reach of the NSA. These included: constructing submarine cables that do not route through the US, building internet exchange points in Brazil, creating an encrypted email service through the state postal system and having Facebook, Google and other companies store data by Brazilians on servers in Brazil. While the first two were an attempt at developing internet infrastructure in Brazil, forcing tech giants to locate their data centres locally to process local communications would have big implications. Not only would it be very difficult to implement at a practical level, but it would not even protect Brazilians’ data from surveillance. On the contrary, data stored locally would be more vulnerable to domestic surveillance. This proposal – even made with good intent – was sending the wrong message, especially to other countries looking to Brazil as a leader in this space. Engineers and web companies, who have their own agenda and economic interests, argued it would have a negative impact on Brazilian competitiveness, would be damaging for its tech sector and pose a threat of “internet fragmentation”. In terms of internet freedom, the measure set a dangerous precedent. Indeed, forced localisation of data relates more to measures undertaken by countries that have a reputation of internet control and repressive digital environments, such as China, Iran and Bahrain.

At a time when Brazil is gaining international exposure for defending internet freedom, it is important to stick to a progressive internet governance approach, including at the international level. The international summit on the future of internet governance – NETmundial – kicked off with Brazil reiterating its commitment to a “democratic, free and pluralistic” internet. The signing of Marco Civil da Internet into law by the Brazilian president onstage set the tone of the event: “The internet we want is only possible in a scenario where human rights are respected. Particularly the right to privacy and to one’s freedom of expression,” said Dilma Rousseff in her opening speech. She added about Marco Civil: “As such, the law clearly shows the feasibility and success of open multisectoral discussions as well as the innovative use of the internet as part of ongoing discussions as a tool and an interactive discussion platform”.

The drafting process of Marco Civil and the inclusive consultation process that has involved civil society and private sector from beginning to end served as a model for the organisation of NETmundial. The unprecedented gathering brought together 1,229 participants from 97 countries. The meeting included representatives of governments, the private sector, civil society, the technical community and academics. Remote participation hubs were set up in cities around the world and the NETmundial website offered an online livecast of the meetings.

However, despite efforts to include civil society and despite Dilma Rousseff’s speech in favour of freedoms online and net neutrality, the geopolitics around the event and pressure from some governments and private sector led to a weak, disappointing outcome document. The final version of the “Internet governance principles” document did not even mention net neutrality – a fundamental principle of the internet architecture. Disappointed and frustrated, many internet activists launched a campaign asking governments to take concrete actions to end global mass surveillance and protect the free internet. Some even came to question the multistakeholder model of internet governance.

The multistakeholder model in question

Although the process for discussion adopted by NETmundial appeared inclusive, the multistakeholder model was criticised by internet activists and described as “oppressive, determined by political and market interests”. The balance of power and weak outcome document of NETmundial led them to call the principles of NETmundial “empty of content and devoid of real power”. La Quadrature du Net, which defends the rights and freedom of citizens on the web, called NETmundial international governance a “farce” and the multistakeholder approach an “illusion”.

Although Brazil made considerable efforts to offer an event open to civil society, academics, private sector and all governments, in reality the power of non-government actors, especially of civil society, is relatively weak next to the dominance of governments, tech giants and other powerful private corporations. And, as attractive as the rhetoric of liberty and freedom might be, intrusive governance is still regarded as acceptable by governments of all kinds – even those with apparently progressive attitudes towards an open internet. This is reinforced by fears of virtual crimes and cybersecurity, which are vital areas of government policy, as recently claimed by the Brazilian minister of communications Paulo Bernardo. In Brazil, as well as in India and other democracies, the balance between freedom and security can generate contradictory positions between international and domestic policies, and security arguments have often been used to justify claims for greater state control over critical internet resources, at the risk of falling into the game of repressive regimes.

The future of internet governance is still being discussed and Brazil is under the spotlight. It is not clear yet to what extent Marco Civil will lead to a safer and better online and offline environment. Meanwhile, Brazil should not support approaches that lead to top-down control of the net or forced local hosting of data. In the aftermath of NETmundial, Brazil appears more as a leader and influencer in the global debates on the future of internet governance. However, the outcome of NETmundial underlined Brazil’s vulnerability to pressure from the US, the EU and industrial interests. Brazil must continue to build on Marco Civil in the international sphere and use its clout to promote internet freedoms.

The full report is available in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]

Part 1 Towards an internet “bill of rights” | Part 2 Digital access and inclusion | Part 3 Brazil taking the lead in international debates about internet governance | Part 4 Conclusions and recommendations

This article was posted on 16 June 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Jun 2014 | India, News, Politics and Society

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

How does one gauge if some online communication, especially a tweet or a Facebook post, is “of a menacing character”? How does one determine, even with an iota of objectivity, if such communication can be “grossly offensive”, or causes “annoyance and inconvenience” to another person? And, to top it all, what does it say about the reasonability, let alone legal validity, of a statutory provision which imposes criminal liability on anyone caught in its tangle? If only the legality was an issue. For, it could still be fought out in the courts. But when this provision becomes the basis for an alarming number of instances of vigilantism, spiralling into riots, then the repugnancy hits one smack in the face.

So is the case with Section 66A of India’s Information Technology Act, which reads:

66A. Punishment for sending offensive messages through communication service, etc.

Any person who sends, by means of a computer resource or a communication device,—

(a) any information that is grossly offensive or has menacing character; or

(b) any information which he knows to be false, but for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill will, persistently by making use of such computer resource or a communication device, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and with fine.

As reported, Facebook posts are landing people on the wrong side of the law. Meanwhile, it turns out that the arrestee had the cops set upon him because he had dared criticize the chief minister, so Section 66A becomes a tool for vendetta. To make matters worse, “concerned citizens” have started forming vigilante groups to spot such online posts, and bring the offenders to justice. And as it happens in India, to buttress the allegation of “derogatory” or “grossly offensive”, in almost every case, the provisions dealing with the offences of blasphemy or spreading communal hatred are clubbed with Section 66A. If at all something could be blasphemous to the most elementary tenets of freedom of expression, this could qualify as one.

In the city of Pune, someone posts morphed images of revered historical figures and demagogues, and it sets off a communal conflagration and an orgy of vandalism, leading the police to declare that even those who “Like” Facebook posts which could be deemed “offensive” shall be booked.

Section 66A is modeled on the same lines as that of Section 127(1)(a) of UK’s Communication Act, 2003 because both seek to penalise “grossly offensive” online communication. However, the provision in the UK law was “read down” by the House of Lords in 2006, meaning the Court laid down parameters regarding how it was to be interpreted. In Director of Public Prosecutions v. Collins the Court held that the phrase must be construed according to standards of an open and just multi-racial society, and that the words must be judged taking account of their context and all relevant circumstances. The Lords added that “there can be no yardstick of gross offensiveness otherwise than by the application of reasonably enlightened, but not perfectionist, contemporary standards to the particular message sent in its particular context.” That such rulings do not obliterate the vice of such provisions is proved by what by now has attained notoriety as the “Twitter joke trial”. A frustrated Paul Chambers tweeted – “Crap! Robin Hood Airport is closed. You’ve got a week and a bit to get your shit together otherwise I am blowing the airport sky high!!” and all hell broke loose with the authorities mistaking this venting as one of “menacing character” and booking him under terrorism charges. The House of Lords rescued him from the clutches of the law, but not after we were painfully made aware of the perils of ambiguous legal phraseology.

Even though a constitutional challenge to Section 66A is pending before the Supreme Court, the government, instead of following common sense and unwilling to let go of its power to threaten people into silence, issued a set of guidelines in January 2013, apparently to prevent misuse of the provision. These guidelines mandated that only senior policemen could order arrest under this section. This was nothing but a fig leaf to protect an ostensibly unreasonable law, because no safeguards can protect against blatant arbitrariness when there is statutory sanction for the same.

The spate of violence and persecution which threatens to spiral out of control couldn’t have come as a more dire warning to the Indian government- that Sec 66A must be repealed sans further ado, and more criminalization of free speech.

This article was posted on June 16, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![Read the full report in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/brazil-cover.jpg)