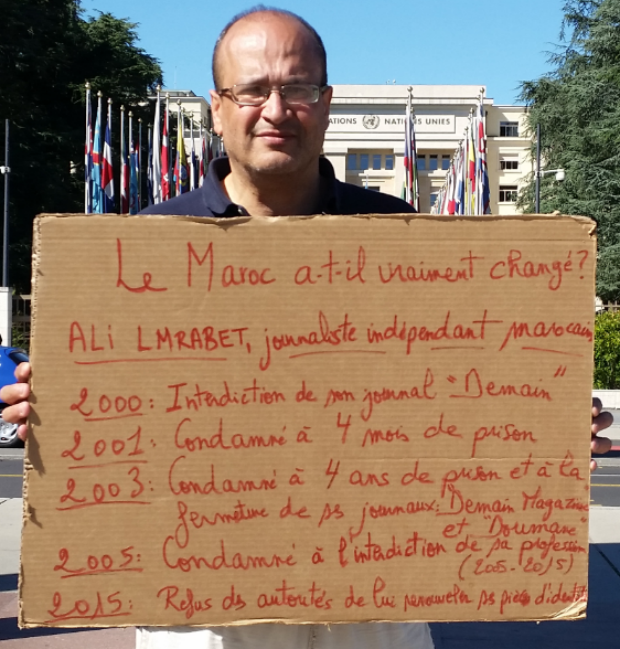

22 Jul 2015 | Middle East and North Africa, mobile, Morocco, News and features

Outside the United Nations building in Geneva, Switzerland, Ali Lmrabet is in his 28th day of a hunger strike. The journalist and satirist is protesting what he sees as the latest bid from his country Morocco to stop him from doing his job.

In a period spanning over a decade, Lmrabet, who was the editor of two satirical publications, has continuously been targeted by Moroccan authorities. In 2003, he was jailed for reporting on personal and financial affairs of Morocco’s King Mohammed VI. His magazine Demain was banned. Though initially handed down a three-year sentence, Lmrabet was released after six months. But his troubles were far from from over: in 2005, he was banned from practising journalism in his home country for ten years, over comments made about the dispute in Western Sahara between Morocco and the Algerian-backed Polisario Front.

Now authorities are seemingly using bureaucracy as a tool to try and silence Lmrabet again. As his ban expired in April this year, he returned to Morocco with the aim of relaunching Demain. But there he was denied a residency permit, without which he is unable to set up the magazine. In a further complication, he also needs the residence permit to renew his passport. When this expired on 24 June, Lmrabet, who was in Geneva to participate in a session of the UN Human Rights Council, decided to start a hunger strike.

“He is very tired,” his partner Laura Feliu told Index on Censorship in a phone interview. She explained how the heat in Geneva has played a part in leaving Lmrabet drained of energy, and while he hasn’t had any serious health problems, he is experiencing sensations of seasickness.

Lmrabet’s protest takes place outside the UN offices, though a heatwave forced him to move inside on Sunday. He sleeps in a Protestant church near the centre of the city. Subsisting on water and some sugar and salt, he has lost at least seven kilograms since the start of the strike.

“He started a hunger strike to protest because he has been denied the right to work as a journalist,” Feliu explained. But in addition to having his free expression and press freedom curtailed, he also has another problem, she adds: “He is denied his right to an identity.”

Lmrabet has support in his country. Some 100 well-known Moroccans from the worlds of media, human rights and academia have signed a petition to the government calling on him to be allowed to renew his documents and continue his work in journalism. Independent and prominent human rights organisations in Morocco are also backing him, according to Feliu.

The response from Moroccan authorities, meanwhile, has so far been unsympathetic. The country’s UN ambassador Mohamed Aujjar has urged Lmrabet to contest what he labelled an “administrative decision” in Morocco, telling AFP that “you don’t get your papers by staging a hunger strike”. Lmrabet, on his part, is unwilling to risk being stranded in Morocco without papers and the ability to work or leave the country. “No one trusts the judical system in Morocco,” he said.

Feliu says it’s difficult to know what the outcome will be, but that Lmrabet is convinced this is the only way to protest. And he remains hopeful.

“He is very convinced of his fight. He is very convinced of his cause. He says that he has the moral to do it.”

Join us 30 July at Stand Up for Satire, a fundraiser in support of Index on Censorship.

This article was posted on 21 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Jul 2015 | Art and the Law Case Studies, Artistic Freedom Case Studies

Installation image of Spiritual America 2014 at Goldsmiths College. With Permission Xenofon Kavvadias

Spiritual America 2014

Xenofon Kavvadias

As part of Index on Censorship’s programme looking into art, law and offence in the UK, this case study looks at Xenofon Kavvadias’s mission to exhibit Spiritual America by Richard Prince in public, effectively reversing the censorship of the image by Tate Modern who removed it from the gallery and the catalogue of their exhibition Pop Life, Art in a Material World 2009-10. Kavvadias called his exhibit Spiritual America 2014 and it formed part of his MA degree show at Goldsmiths College.

The work illustrates many of the issues raised in Index’s Art and the Law pack on Child Protection, giving useful insights into what happens when a work is contested in this area of legislation, the negotiations with the police and how far the law is open to interpretation.

Introduction

Spiritual America by Richard Prince was exhibited as part of The Tate Modern exhibition Pop Life Art: in a Material World, October 1 2009–January 17 2010. The piece is a reproduction of an original 1976 photograph depicting Brooke Shields, aged 10, naked in a bath. The Tate took the work down apparently on the advice by the Obscene Publications Unit of the Metropolitan Police Service that the image might be in breach of the Child Protection Act 1978. Under pressure from the police, the image of the work was also redacted from the catalogue of the show.

A 14 October 2009 BBC report carried a statement from the gallery that said: “In consultation with the artist, Richard Prince, Tate has replaced Spiritual America 1983 with a later version of the work made by him in collaboration with Brooke Shields, Spiritual America IV 2005. Tate is in ongoing discussions with legal advisors about the catalogue.”

Charlotte Higgins and Vikram Dodd writing in The Guardian on 30 September 2009 reported:

The decision by officers to visit Tate Modern is understood to have been made after police chiefs saw coverage of the exhibition in today’s newspapers, rather than as a result of complaints.

Officers met gallery bosses and are also understood to have consulted the Crown Prosecution Service as to whether the image broke obscenity laws.

A Scotland Yard source said the actions of its officers were ‘common sense’ and were taken to pre-empt any breach of the law. The source said the image of Shields was of potential concern because it was of a 10-year-old, and could be viewed as sexually provocative.”

The Tate chose not to include the original picture in Pop Life: Art In A Material World, after seeking legal advice.

Research leading to the presentation of Spiritual America 2014

Kavvadias undertook to display Richard Prince’s Spiritual America in his MA show at Goldsmiths, which he called Spiritual America 2014. As well as displaying a framed replica of the artwork, a record of all his research was available to the viewer to place the image in context. Gaining as full an understanding as possible of the legal and policing positions regarding the removal of the image from the Tate in 2009 was his point of departure.

Freedom of Information Requests

Kavvadias issued FoI requests to the Tate, the Police and the CPS. All FoI correspondence was included in the exhibition.

Key findings:

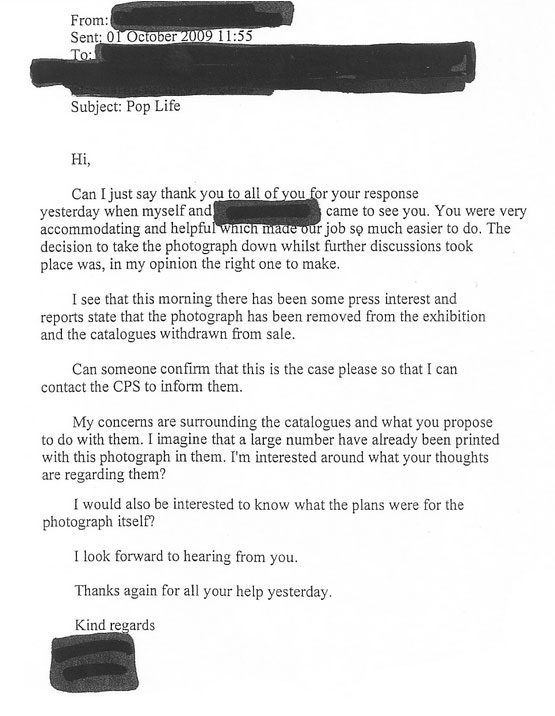

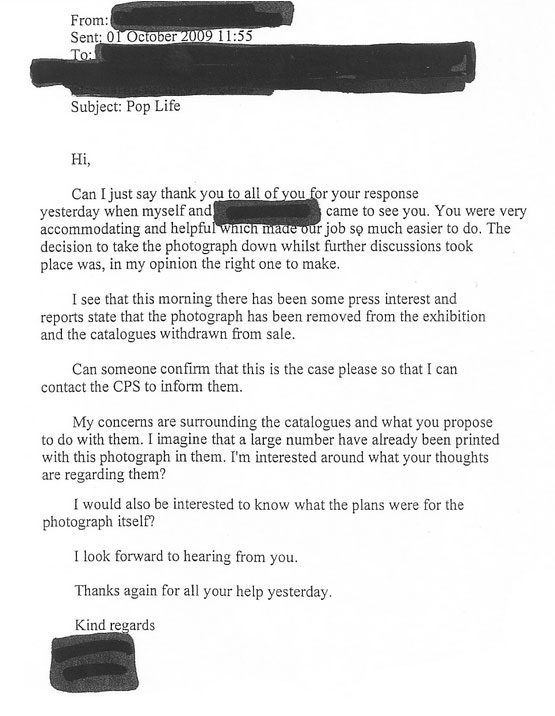

1 October 2009: The police wrote an email to the Tate regarding their visit:

2 October 2009: The police continued to put pressure on the Tate about their plans for the catalogue, writing a follow up email to the one above the next day.

6 October 2009: The Head of Director’s Office, Tate wrote to the trustees:

[Formalities]…we felt that given the important issues at stake (acting within the law while defending artistic freedom of expression) and the level of public interest in the case that we should keep each of you as individual trustees informed.

At the request of the owner and as provided for under our loan agreement with him, we have returned the work to him. In light of this, we have also consulted with the artist and are considering the option of substituting the work with another worked titled Spiritual America IV.

The Tate Enterprises Ltd board will meet…to discuss their position and options with regard to the distribution of the catalogue. Legal advice has been sought to inform their decision from leading counsel and specialist solicitors. …In the meantime the catalogue will continue to be withdrawn”

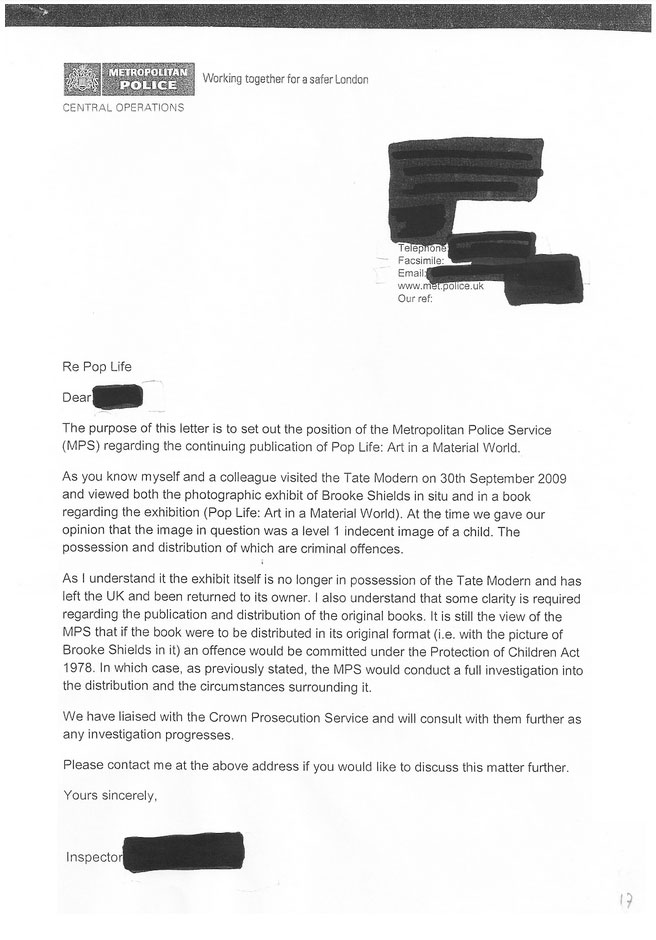

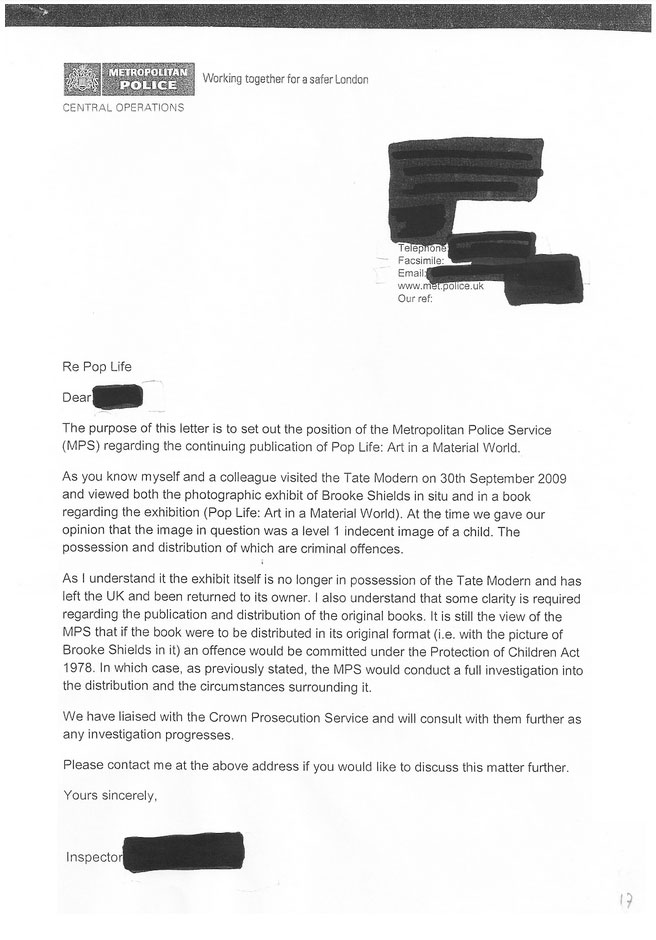

The Metropolitan Police Obscene Publications Unit wrote regarding their position as requested by the Tate:

- 12 October 2009: The catalogue was removed from sale while the Tate was taking legal advice.

- 13 October 2009: Metropolitan Police Service Directorate of Public Affairs Central Operations Press Desk, writing to head of communications at the Tate: “I’d just like to raise how categorical you interpret the police advice as having been. We did not state that we definitely considered the image to be indecent but explained that it may be, and that if it was then an offence would be committed if it was displayed. Police can never say when someone will be prosecuted, as that is a decision for the CPS, but did inform yourselves we would consult with the CPS. This is the MPS position as we have been and will continue to, explain to reporters.”

- 13 October 2009: The plan to obscure the image was in place.

- 13 October 2009: Tate asked Richard Prince for approval to obscure the image on the catalogue.

- 16 October 2009: In an email written to the police in support of including the image in the catalogue, Nicholas Serota compiled a list of freely available books featuring “Spiritual America”. Serota, who was Deputy Director of the Tate at the time, wrote: “As outlined already, we presented the work in the exhibition and catalogue because of its art historical significance in the study of 20th century art, as well as its intrinsic artistic merit”.

- 28 October 2009: The decision was made for the director of the Tate to write to the director of Public Prosecutions seeking clarification on the legal position concerning the work, and guidance on whether a prosecution would follow should the catalogues be distributed again. There is no written reply to this request. However, in 2013, Index spoke to the former DPP, Sir Keir Starmer who had been in post at the time of the controversy, and he said that he received many letters from arts organisations with similar requests but he cannot give advice as to whether a prosecution would follow. This is the work of the courts. However he felt there was a strong case for drawing up guidelines on how CPS reached a decision when considering whether or not to prosecute where artwork is involved.

- The legal advice was redacted from the FoI though the explanation of the offences and possible sentencing was made available. See below:

Additional Research

Availability of the image

Kavvadias carried out his own research into the availability of the image in books mentioned in Serota’s list, one of which was written by a professor at Goldsmiths. He researched the libraries of four leading art colleges in London and the British Library, where he easily located the books. He sent an FoI request to the British Library for their position regarding the advice Metropolitan Police gave to Tate. The British Library replied after two months, with a full and considered response robustly defending the books.

Ethics approval from Goldsmiths

The fact that one of the books containing the image was written by a Goldsmiths’ professor reinforced the view held by all of the committee that the Richard Prince picture is an accepted artwork. However, given that this defence failed to convince the legal team working with the Tate, it was not enough itself. They wanted reassurance on three additional concerns:

- the possibility of harm, including damage to reputation of the minor in the original

- that displaying the image might be in breach of copyright

- that the image was not presented in a sensational way that could bring the college into disrepute; they retained the right to withdraw until Kavvadias’ work was in situ in his exhibition

Issue of harm

Kavvadias addressed the issue of harm by presenting the history of the image:

- The original image, by Gary Gross, was commissioned by the Playboy publication Sugar ‘n’ Spice in 1976. Consent was given by Brooke Shield’s mother. She was paid $450 for the rights to the image.

- In 1983 Brooke Shields sought an injunction from the New York State Court of Appeals to bar further publishing of the image. Her motion was denied. According to the court’s ruling, “It should be noted that plaintiff did not contend that the photographs were obscene or pornographic. Her only complaint was that she was embarrassed because ‘they [the photographs] are not me now.'” While the judges found that the photographs were not pornographic, the court left in place an earlier decision that barred the sale of the photo to pornographic magazines.(Shields v. Gross, 58N.Y.2d338,448 N.E.2d108,461 N.Y.S.2d 254,9 Media l Rep. 1466 (N.Y.1983).

- Richard Prince purchased the rights to the image after the court ruling.

- Prince displayed the framed image with the title Spiritual America in 1983 in a New York gallery he rented, amid considerable controversy. Prince later created an edition of 10 prints.

- The image has subsequently been displayed in galleries around the world:

- Valencia, IVAM Centre del Carme, Spiritual America, 1989 (another example exhibited).

Cologne, Museum Ludwig, Ars Pro Domo, May-August 1992, p. 238 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Dirty Data, June-August 1992, p. 75 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, Whitney Museum of American Art; Dusseldorf, Kunstverein; San Francisco, Museum of Modern Art; and Rotterdam, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Richard Prince, May 1992-November 1993, p. 86 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- Munich, Kunstverein and Hamburg, Kunsthaus, Someone Else with my Fingerprints, April-July 1998, p. 75 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, Museum of Modern Art, Fame After Photograph, July-October 1999 (another example exhibited).

- New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, The American Century-Art & Culture 1950-2000, September 1999-February 2000, p. 285, no. 466 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- Minneapolis, Walker Art Center; Paris, Centre Pompidou; Mexican City, Museo Rufino Tamayo and Miami Art Museum, Let’s Entertain, February 2000-November 2001, p. 254 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- Basel, Museum für Gegenwartskunst and Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, December 2001-July 2002, Richard Prince: Photographs, p. 115 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, New Museum of Contemporary Art, East Village USA, December 2004-March 2005, pl. 113, p. 75 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; Minneapolis, Walker Art Center and London, Serpentine Gallery, Richard Prince: Spiritual America, September 2007-Summer 2008, p. 46 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Pictures Generation 1974-1984, April-August 2009, pl. 231 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- London, Tate Modern; Hamburger Kunsthalle and Ottawa, The National Gallery of Canada, Pop Life: Art in a Material World, October 2009-September 2010, pp. 123 and 196.

- Source: Christies

- In 2005, Brooke Shields, 40, posed for Richard Prince, in a bikini, taken in a similar pose to the original.

- Spiritual America was auctioned for $3,973,000, Sale 3495, at If I Live I’ll See You Tuesday: Contemporary Art Auction 12 May 2014 New York, Rockefeller Plaza

Richard Prince on Spiritual America

“In 1987, after I joined up with Barbara Gladstone, I editioned it. Ten copies and two APs [artist’s proofs]. I had my lab print it on ektacolor paper at 20 x 24”. The first one I sold, was to Stephan, my plumber friend and drummer for the Glenn Branca band. I sold it to him for a hundred dollars and some plumbing work. A couple of years later, I heard he sold that copy to Jay Gorney for four grand. Ten years after that Myer Viceman sold the original 8 x 10” back to Barbara Gladstone for two hundred thousand dollars. Then the 8 x 10” sold to Per Skarsted and later he made a special room for it, (all alone… painted the walls red) and showed it at Art Basel and sold it to Michael Ringier for one million dollars. A couple of years ago Michael lent it to the Tate Modern for some POP show organized by Alison Gingeras and Jack Bankowsky and it was ‘confiscated’ by the London police. The Tate didn’t do much protesting… they caved in to the ‘authorities’ and let them cart it away. It was never re-hung at the Tate and it was eventually returned to Michael Ringier. (Last I heard, Michael lives with Spiritual America in his home outside of Zurich).” Source: ASX

Copyright Infringement

As for possible copyright infringement, because Kavvadias was making a replica of the entire work, including placing it in a frame similar to the one used by Richard Prince, he had to demonstrate clearly to the university that he had the relevant permissions. Given that Richard Prince based his career on copying images and putting them into a new context, Kavvadias did not anticipate a problem. Kavvadias was using the image under Fair Use in US Copyright law for non-commercial and/or academic purpose. However, in order to reassure Goldsmiths, he took two steps:

He tweeted Richard Prince that he had been accused of copying his work. Richard Prince retweeted his message.

Kavvadias wrote to Prince’s London gallery informing them that he was attempting to legitimise the artist’s work that had been criminalised in the UK. They wished him luck.

Legal Advice — Second Opinion

Kavvadias interviewed lawyer Mark Stephens of Finers Stephens Innocent on 4 February 2013, regarding the legal advice given to the Tate to redact the image. Stephens made it clear he didn’t think there was any possibility that the CPS would have recommended a prosecution. Taking the CPS three stage test of whether to prosecute: the first, which asks is there sufficient evidence, is covered, because the image is the evidence. But he claimed it would have failed the other two:

- “that there has to be better than 50% chance of a successful prosecution: ‘Although I could see several charges that could be laid, [they] would be very difficult to succeed.'”

- “that it has to be in the public interest. Stephens stated that, in his opinion, it was not in the public interest to ‘bring the prosecution against Britain’s foremost cultural institution when the image has been around since the seventies, the culture across the planet have shown it and exhibited it without complaint. Even if you prosecute successfully this particular institution, which was displaying just one copy of this image, this was not going to eradicate the image, this was not going to eradicate any harm. If there was any harm, that occurred when this image went viral, effectively when it went on the internet…'”

The Police

Kavvadias wrote to the police informing them that he intended to display this work as part of his Masters thesis at Goldsmiths and gave them the dates. He didn’t ask them for advice or permission. He kept the email trail as evidence of his transparency. They didn’t respond.

21 Jul 2015 | Art and the Law Case Studies, Artistic Freedom Case Studies

A scene from The Freedom Theatre’s UK tour of The Siege. Image courtesy of The Freedom Theatre

Throughout Index on Censorship’s Art and the Law information packs, the lawyers who wrote them stress that the packs offer guidance only and are not a substitute for legal advice. Knowing about the law helps an artist or an organisation identify when there could be a legal issue arising from an artwork. But each artwork is case specific so the advice is to contact a lawyer, if you are in doubt about whether or not you may be in breach of the law.

This short case study of the Palestinian Theatre Company’s first UK tour illustrates how the legality of The Siege was challenged in the media and how the touring venues responded to meet the challenge.

Background

The Freedom Theatre’s first UK tour, 13 May-20 June 2015, took the premiere production of The Siege to 10 UK venues: The Lowry, Manchester; Lakeside Theatre, Colchester; Battersea Arts Centre, London; The Hub, Leeds; St Mary in the Castle, Hastings; The Merlin, Frome; Birmingham Rep, Birmingham; The Cut, Halesworth; The Tron, Glasgow.

The show tells the story of the 2002 siege of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, which was an international news story. The production illustrated the siege from the perspective of the Palestinian fighters who spent 39 days inside the church. The company researched the show by interviewing some of the fighters who are now living in exile in different countries.

In programming The Siege, Battersea Arts Centre (BAC) had anticipated that it and other participating venues might receive some critical feedback connected with the tour. Indeed, the 3 May 2015 Mail on Sunday contained an article with the headline: UK taxpayers fund ‘pro-terrorist’ play – £15,000 of public money given to show based on the words of Hamas killers. The Times of Israel also reported on the production with the strapline – “2002’s hostage standoff at Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity gets historically questionable treatment in play set to tour England”

The BAC responded to the media reports. This is an excerpt from the briefing document:

- Battersea Arts Centre has agreed to help the Freedom Theatre in their liaison with the press in the UK and to act as a go-between between the company and the other 9 venues on the tour

- We are seeking legal advice from freedom of speech lawyers to reassure ourselves that nothing in the show is in contravention of UK counter-terrorism legislation

- We are looking carefully at the curation of discussions alongside the show which give the opportunity for points of view opposed to the Freedom Theatre point of view to be aired

- We are talking to our Board, funders and others to brief them on the current situation, to share information and to take their advice

- In the light of recent articles we are updating an internal document of Q&As to help us answer any questions likely to be levelled at us or other venues from the press/others. The key principle espoused in these answers is that Battersea Arts Centre (as is true of most if not all of the other venues on the tour we imagine) are providing a platform to this theatre company in the interests of freedom of expression, but BAC is not subscribing to any one particular point of view. We have previously given a platform to a theatre company that presented a piece from an Israeli perspective on the conflict in Israel/Palestine”

This last point, by referring to freedom of expression, cites the venues’ right to freedom of expression as laid out in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Seeking legal advice

In the Q&A mentioned above, one question raised a legal issue: Does this play glorify terrorism? It was also echoed in the media that alleged the play was “pro terrorist”.

Glorification of terrorism is a crime with serious consequences if convicted. While the guidance in our pack goes into some detail of defences for artists and arts organisation, it also stresses that the pack is not a substitute for legal advice. If you are unsure about your responsibilities under the law at any time, you must obtain independent specialist legal advice.

In order to be as confident as possible of the content in The Siege, BAC sought independent legal advice from three different sources: a Trustee contact; an Arts Council contact; Liberty. The Lowry also sought independent legal advice.

This was a sensible belt and braces approach because lawyers’ advice often varies according to interpretations of the law. Lawyers can only advise after all, so it was sensible to go three ways. All three gave advice pro-bono.

BAC created a summary statement from this advice and shared it with the other nine venues. They included a disclaimer that other venues used it at their own risk. It was advice, rather than a watertight guarantee that there couldn’t be other interpretations placed on the script. But it succeeded in its main purpose, which was to reassure the touring venues of their legal position, and enabled them to stand up to hostile press if necessary.

The statement helpfully demonstrates how freedom of expression is qualified by other considerations. In other words, once the lawyers were satisfied that the play didn’t breach legislation, then the right to freedom of expression can be upheld. Here is the summary:

The Siege does not infringe Section 1 of the Terrorism Act 2006, which prohibits the encouragement or glorification of terrorism. The play focuses on the personal struggles of the Palestinian fighters on a human level in attempting to survive the siege. It does not encourage audience members to emulate their conduct. Although the play is likely to be interpreted as sympathetic to the fighters, the sympathy is based on their struggle to survive as people and not on any violent acts or participation in terrorist groups. Violence is at no point encouraged in the play.

The presentation of The Siege, which depicts real-life events expressly from the point of view of the Palestinian fighters, is covered by Article 10 of the Human Rights Act: the right to freedom of expression, including artistic expression. Since The Siege does not commit an offence under the Terrorism Act 2006, and therefore poses no reason for this freedom of expression to be curtailed, prohibiting the play would likely be a breach of Article 10.”

David Jubb, artistic director of Battersea Arts Centre, reflected on the tour:

It was interesting to see the way that language was used in some of the reporting of The Siege. As well as raising the general temperature around the tour and adding to a sense of controversy, the use of legalistic language also introduced questions about the legal status of the show.

We felt that seeking legal advice would be useful to us in a number of ways: to inform our Q&As so that we could confidently answer any question that posed a direct legal challenge to the work; and to settle any anxiety that any staff or Trustees might understandably feel, to demonstrate that the artists and the organisation were on a solid legal footing.

This latter point was especially useful for Trustees who are one-step removed from the day-to-day and for good governance in these matters must be reassured that all risks have been assessed. Perhaps the most productive decision was made by all participating venues together: that we would support each other in the run-up to and during the tour, and work closely with the company at all times.

I know that we at Battersea Arts Centre learnt a lot from the great work of the Lowry and others. Providing each other with a support network ensured that we felt less isolated during stressful moments.”

A short survey was sent around to the venues on the tour asking if there were protests and about their contact with the police. The feedback was that the police were supportive and responsive and acted as useful liaisons between the venue and the protesters. Most venues informed the police of the forthcoming production about one week in advance. One venue approached the police a month in advance, but it seemed to “get lost in the system”. There were protests at many of the venues, but all were peaceful and took place without incident.

21 Jul 2015 | Art and the Law Case Studies, Artistic Freedom Case Studies

Installation image from Xenofon Kavvadias: The law is no less conceptual than fine art at 10 Vyner Street. With permission of the artist.

“The law is no less conceptual than fine art”

Exhibition of Illegal Books by Xenofon Kavvadias

10 Vyner Street London E8

5th May – 17th June 2011

Description of the work

In this show books that are or can be considered illegal under contemporary UK anti-terrorist legislation were displayed as an art installation. The books represented the full spectrum of ideologies and beliefs that can be considered illegal in the UK.

The books were uniformly hard-bound without titles, accompanied by text describing the content and context in which it was published. Background information, correspondence and records of interviews were displayed in the gallery.

The gallery was well lit and the viewer was encouraged to take time to read the books and accompanying information. Each week of the six-week exhibition, one book that could not exist outside the specific conditions that were created in the gallery was burned and the ashes were displayed in specially made glass vases. By the end of the exhibition, all such books were burned.

In the installation Kavvadias explicitly stated that the documents neither expressed his views nor had his endorsement.

Background

Kavvadias started the project in 2005 believing that the new anti-terrorist legislation was highly problematic and represented an erosion of civil liberties – a hypothesis that he wanted to test as an artist, from the standpoint of an individual, independent investigator who has unique access through exhibition to the public, the media, the law and the policy maker.

I am not a lawyer, in fact when I started out I wasn’t sure what I was. The choices seemed to be: journalist, activist, artist. I chose the latter.”

The legislation

As the Report of the Eminent Jurists’ Panel on Terrorism, Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights 2009 noted:

Many participants at the U.K. hearing raised concerns that the breadth and the ambiguity, of the offence of ‘glorification’ create a risk of arbitrary and discriminatory application. The risk of such abuse is exacerbated by the fact that the offence applies also to past acts of terrorism and to terrorist acts occurring in other countries. Witnesses expressed concern that such wide-ranging laws reduce legitimate political debate, particularly within immigrant or minority communities.”

Aware of the grey areas the legislation created, Kavvadias’ show was an attempt to plot the margins of legality with regard to counter terrorism legislation – what can be seen, said or thought.

The methodology

Kavvadias identified the steps he needed to take to be able to demonstrate, in court if necessary, that his motivation was as an artist. The artwork was both his presentation of texts and objects in a carefully curated space, and the evidence for his defence.

Here is a brief summary of his interactions with the police, lawyers and a member of the House of Lords, who helped him to answer the underlying questions his project raised.

The Police

Having first secured support for this project from Leeds Metropolitan University where he was studying at the time, Kavvadias approached the police and had an hour-long interview with the Counter Terrorism Special Branch in Leeds. He made a record of the interview during which he went through a list of the materials he thought he could not present. He asked the police to respond to these materials during the interview. He was asking for advice, not permission.

The police tried to advise Kavvadias on what — in their view, following available guidance — he could and couldn’t collect and discussed examples of material that had been used by the police to secure convictions.

The police always had a feeling of a line – ‘if you cross the line it will be illegal and we will have to arrest you’. This is a preventative measure from the police – they want to present a line, they don’t want to give you the grey area, so that you stay safely within the legal side. Even if later the court might say – ‘no there is no case’. The police have an interpretation of the law and this understanding is later modified by a court.”

The State Machinery

Kavvadias wrote to the Press & Broadcasting Advisory Committee (DPBAC) at the Ministry of Defence (MoD) asking if he could display restricted MoD documents that he found on Wikileaks. He received the following reply:

“I have no objections from Defense Advisory Notice standpoint to your displaying the first and second pages of the subject document as part of your project.”

With this letter to support him, Kavvadias displayed the first and second page of a document, leaked by Wikileaks, that gives an idea of the level of surveillance capabilities of the UK.

The Lawyers

The first legal opinion Kavvadias sought was from Liberty and he got a very detailed letter back, explaining how the legislation can be applied, where he needed to be extremely careful and how he should position himself. “It was very illuminating and very useful and it was one point of view,” Kavvadias said.

Kavvadias then approached Gareth Pearce, a British solicitor and human rights activist, who connected him with Alastair Lyon one of her team, and subsequently talked to Matrix Chambers’ Matthew Ryder QC in detail about his project. All the lawyers he approached supported the project and thought it was an important piece of work. While they disagreed about what was the greatest specific risk, the lawyers agreed that extreme care should be taken on how the whole show would be staged.

All agreed that at the entrance of the gallery there should be a very clear public disclaimer that the artist and gallery do not advocate violence and to distance themselves from the content. It should be made absolutely clear that the exhibits were to be seen and discussed, but not recorded — no photography, no note taking — to minimise dissemination. No part of the installation should be available on the internet.

The biggest challenge was the contradictory advice – ultimately you have to make up your mind – Liberty, MR, Lord Carlile – all liked the project. No-one took an absolute position so it was my decision. I felt I had the information – the facts were in front of me and I had to make up my mind to stick with it.”

The Law Lord

Encouraged by the support from the lawyers, Kavvadias went on to one of the highest authorities in the land – Lord Carlile of Beriew, Independent reviewer of terrorism legislation UK 2011– a Law Lord. He wrote to Carlile and received the following reply:

Thank you for your letter of February 25th.

I was interested by your MA project and am sure that there is a visual art context into which counter-terrorism legislation can be put.

Artists sometimes take risks with the Law to achieve full expression, however the Law will not be suspended for such projects. When people take a close interest in terrorism websites, or sites containing material that might prove of interest to terrorists, the authorities would be negligent if they did not take an interest in such activities, if aware of them. I am sure that you are exactly as you describe, an artist acting in good faith, but the police and others will not necessarily take that at face value and understandably so.

The authorities are under no obligation to advise whether proposals made by a citizen will lead to prosecution, and there is case law to say they need not do so. Indeed the giving of such advice would be a departure from normal practice by both the police and the Crown Prosecution Service. In the event of prosecution being considered the CPS would certainly take into account Zafar1 in assessing whether there was enough evidence or whether or prosecution was in the public interest.

The best and short answer to your question is that you are unlikely to be prosecuted and if prosecuted, not convicted, if you do not break sections 57 or 58 of the Terrorism Act 2000. The responsibility for what you do is yours: I am sure you are conscious of this, and in following your studies, document what you do and why by notes.

I am sure that your course supervisors will advise you on boundaries with the advantage of knowing your work. Central St Martins is an excellent and celebrated art school and the staff there possess well-honed judgement about the boundaries between conceptual art and politics and the Law.

I am sorry that I cannot answer your question more directly, but I am afraid that the Law is no less conceptual than fine art.

Best wishes

Yours sincerely

Signed –

Alex Carlile.

1. R v Zafar & others [2007] Imran Khan and Partners represented Aitzaz Zafar when in 2007 he, together with Irfan Raja, Awaab Iqbal, Usman Malik and Akbar Butt were jailed for between two and three years each by the Old Bailey for downloading and sharing extremist terrorism-related material, in what was one of the first cases of its kind. The prosecution alleged that they had collected extremist material for the purposes of terrorism. The men argued that they had no real terrorism links and were driven by intellectual curiosity. Four of the men were students at the University of Bradford. Following their convictions, the men appealed and on the 13/02/2008 the Court of Appeal overturned their convictions. In their ruling, the three Appeal Court judges said the trial jury should have been told to decide whether there was a connection between the extremist literature and a clear terrorist plan. http://www.ikandp.co.uk/ViewCaseStudy.asp?CaseID=76

Having managed to engage a high level politician and lawyer, Kavvadias felt that it would be extremely hard for the police to characterise him as someone who was acting recklessly.

The Gallery

10 Vyner Street gallery owner Peter Gallagher-Witham was interested in freedom of speech and felt it was worth investing in and thought it was a good work of art. He also felt that it was controversial and would attract attention. Despite the gallery owner’s belief in the work, he had a lot of reservations; he was worried that the police would come to the gallery and he would be accused of dissemination of terrorism.

He really wanted some sort of reassurance, but there is not an absolute reassurance. There are steps that can minimize risk. I never expected a public gallery to take this work because of the nature of the work being too contentious.

This was the last exhibition in 10 Vyner Street, which closed at the end of Kavvadias’s show.

The Reaction

Like most artists, Kavvadias wanted publicity for his work, but in this case, it was not just the exposure for the work that he was looking for. The press was interested because Lord Carlile, a senior law lord, had responded to an artist; this was newsworthy. The Guardian wrote an article which took the project into the public domain, opening it to scrutiny by an infinitely wider group, including the police. During the exhibition, Sir Allan George Moses, a former Court of Appeal judge, visited the gallery and left a positive comment. The police did not openly visit the gallery.

There were no legal repercussions for Kavvadias as a result of the exhibition.