15 Sep 2016 | Tim Hetherington Fellowship

Award-winning photojournalist Tim Hetherington’s ‘Infidel’ exhibition had an emotional opening in Liverpool this week. The exhibition, being held at LJMU’s John Lennon Art and Design building, features moving and intimate images of American soldiers stationed in Afghanistan. Read in full at JMU Journalism.

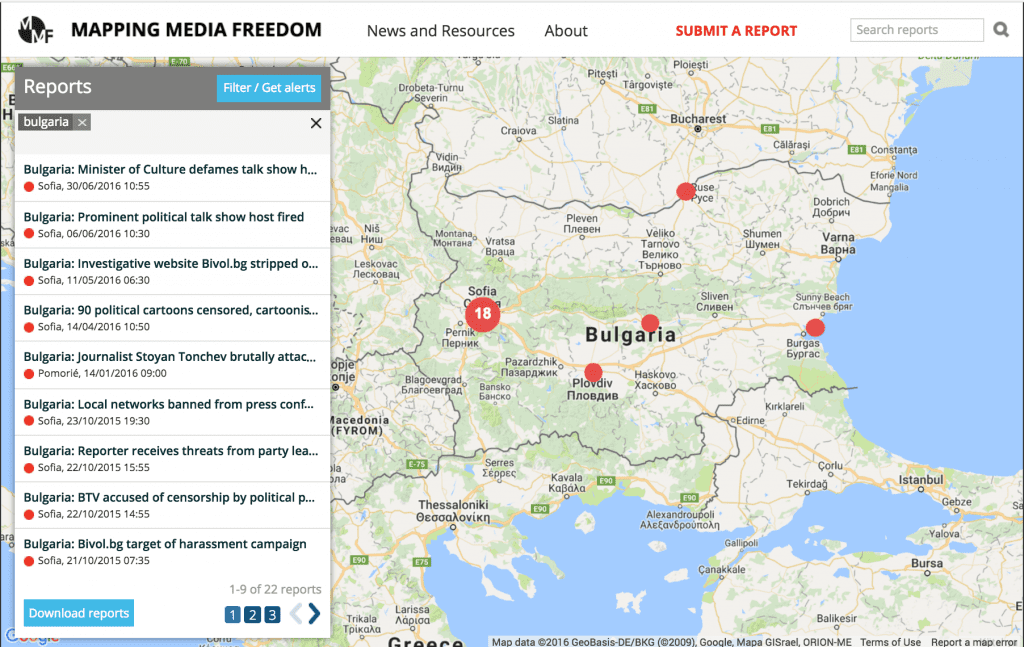

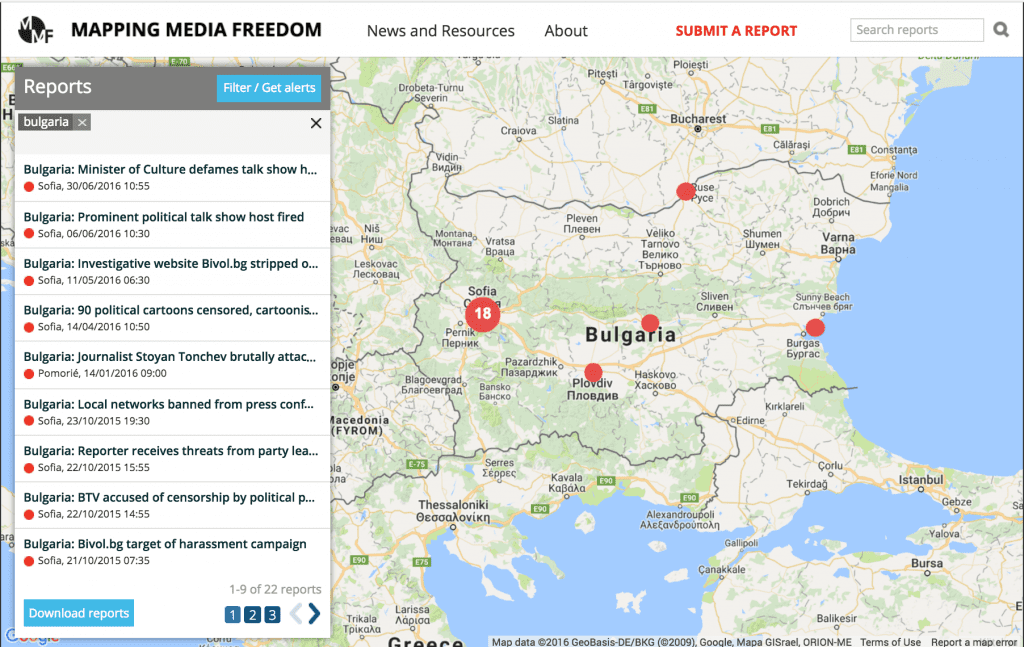

15 Sep 2016 | Bulgaria, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Between 2013 and 2015, 10 Bulgarian municipalities spent a total of 2.7 million Bulgarian lev ($1.54 million) – mainly to media companies and PR agencies – in return for positive coverage of their activities, an investigative series by news site Dnevnik.bg found.

According to the articles, the local governments of the five largest, excluding the capital Sofia, and five of the poorest cities in the country were found to be engaging in “corrupt practices” and displayed a disregard for “journalistic ethics and loyalty to the audience”.

Under the guise of using contracts to create advertisements, “job posting messages and other texts” – not only in publications but also for radio and television broadcasts – all 10 municipalities were found to be buying influence in media outlets and attempting to eliminate criticism, Spas Spasov, the author of the series, told Index on Censorship. The cities reviewed were Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Pleven, Stara Zagora, Shumen, Kazanlak, Blagoevgrad, Vratsa and Montana.

The data, which was obtained through freedom of information requests, does not claim to be exhaustive but provides an indication of administrative control over news in the cities covered by the investigative reports. “The idea behind the project was to reveal the deep crisis in which freedom of the press finds itself in Bulgaria,” Spasov said.

One visible trend in the series is that media content is sold at a discount to local governments who buy “wholesale”.

“The results of my investigation show that virtually all the media in the analysed municipalities are dependent on the public funding they get,” Spasov told Index. The lack of an advertising market outside the capital only strengthens this dependence on handouts from local government, he added.

|

This article is a case study drawn from the issues documented by Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project that monitors threats to press freedom in 42 European and neighbouring countries.

|

|

He found that in many cases the money private media outlets receive from municipal administrations often covers the entirety – or at least a significant portion – of their budgets. In one case a source told Spasov that the entire salary of a journalist was covered by Vratsa municipal funding.

In the city of Varna some advertising contracts were signed by municipal companies that are monopolies that were not in need of advertising. Spasov said that this is a way to buy political and institutional influence in a media outlet.

Many municipalities were found to be contracting “advertising” and “promotional activities” through private media despite the fact that almost every municipality has its own municipal media, through which they already publish official announcements.

“Of course, there is nothing vicious in the practice of municipal administrations buying advertising in private media,” Spasov said. He does, however, stress that in order to avoid buying media influence, local administrations and government institutions should publish their advertisements only in media outlets that comply with the Ethical Code of the Bulgarian Media.

“This code clearly stipulates that all text covered by the contracts will be marked as sponsored content but this is not the current practice,” he said, adding that vague wording–phrases such as “other texts”–helps to disguise sponsored articles published as editorial content.

This is possible because Bulgaria has no law requiring print and online media outlets to label sponsored content they are publishing. Existing regulation only addresses television advertisements.

“Transparency of sponsored content is crucial for a functioning free press. It is vital that existing legislation on advertisers be reformed swiftly to include all media outlets in order to protect the public,” Hannah Machlin, project officer for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, said.

The investigation went on to find that many media outlets from smaller municipalities were created by political entities with the purpose of bullying their opponents in local government.

Spasov told Index that if the remainder of the country’s 256 municipalities were also to be investigated, “there should be no doubt” that the findings would be similar to the 10 which were analysed in his investigation.

14 Sep 2016 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

Jailed Turkish journalist Ahmet Altan.

If made out of the right stuff a journalist is a tough nut. Some of us are, you may say, born that way. Our profession lives in our cells. We are compelled to do what our DNA instructs us to do.

Yet, these days, I can’t help waking up each morning in a state of gloom.

Never before have we, Turkey’s journalists, been subjected to such multi-frontal cruelty. Each and every one of us have at least one — usually more — serious issue to wrestle with. Many have already faced unemployment. According to Turkey’s journalist unions, more than 2,300 media professionals have been forced to down pens since the coup attempt. The silenced face a dark destiny: they will never be rehired by a media under the Erdogan yoke.

More than 120 of my colleagues are in indefinite detention – and that number does not include 19 already sentenced to prison. The latest to be added to the list are the novelist and former editor of daily Taraf, the renowned journalist Ahmet Altan and his brother, Mehmet Altan, a commentator and scholar.

The grim pattern of arrests comes with a note attached: “To be continued…”

Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk recently and eloquently summed up what Turkey is becoming: “Everybody, who even just a little, criticises the government is now being locked in jail with a pretext, accompanied by feelings of grudge and intimidation, rather than applying law. There is no more freedom of opinion in Turkey!”

Some of those who are still free, either at home or abroad, may consider themselves lucky – or at least be perceived as such. But the reality is that each and every one of us faces immense hardship.

Being forced into an exile, as I have been, is not an easy existence. Many like me have an arrest warrant hanging over their heads. Others are simply anxious or unwilling to return home.

Pressured by financial strains, a journalist in exile bears the burden of the country they have been torn from while remaining glued to the agony of others.

But there is more. Last week I offered one of my news analyses to a tiny, independent daily — one of the very few remaining in Turkey. Waiving any fee, I asked the editor — who is a tough nut — to consider publishing it. Soon, the text was filed and the initial response was: “This one is great, we will run it.”

Then came a telephone call. Because the editor and I have a friendly relationship, he was open when he told me this: “As we were about to go online with it, one editor suggested we ask our lawyer. I thought he was right in feeling uneasy because everything these days is extraordinary. Then, the lawyer strongly advised against it. Why, we asked. He said that since Mr Baydar has an arrest warrant, publishing a text with his byline or signature would, according to the decrees issued under emergency rule, give the authorities to the right to raid the newspaper, or simply to shut it down. Just like that. Tell Mr Baydar this, I am sure he will understand.”

I did understand. No sane person would want to bear the responsibility for causing the newspaper’s employees to be rendered jobless, to be sent out to starvation.

I have since published piece elsewhere.

This incident is but one in a chain, hidden in Turkey’s relative freedom. It’s a cunning and brutal system of censorship that aims to sever the ties between Turkey’s cursed journalists and their readership. It is a deliberate construction of a wall between us and the public. It is putting us in a cage even if we are breathing freedom elsewhere.

It’s enough to make George Orwell turn in his grave.

But there is some consolation. Thankfully we, the censored among Turkey’s journalists, have space to write about the truth, make comments and offer analysis in spaces like Index on Censorship. Thankfully, we have the internet, which is everybody’s open property, even if the sense of defeat when you awake some mornings leaves you convulsing in the gloom.

You know you have to chase it away and get on with what you know best: to inform, to exchange views, offer independent opinion, promote diversity, and hope that one day it will contribute to democracy.

More Turkey Uncensored

Can Dündar: “We have your wife. Come back or she’s gone”

Turkey: Losing the rule of law

Yavuz Baydar: As academic freedom recedes, intellectuals begin an exodus from Turkey

13 Sep 2016 | mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

In mobster movies the bad guys always kidnap the wife of the protagonist. They’ll phone the husband to say: “We have your wife. Do as we tell you otherwise she’s gone.”

I had not imagined that a state could become no better than a criminal syndicate. But the Turkish state has become one.

On Saturday 3 September my wife’s passport was confiscated by the police at the airport as she was en route to Berlin. She was not accused of anything criminal. She was not being searched for or tried and had no obstacles preventing her from travelling abroad. There was no legitimate reason to prevent her journey and no explanation has been given.

It is with me that they had an issue. I had broadcast footage of Turkish state intelligence smuggling arms into a neighbouring country by illegal means. They could not deny it and say: “No such thing has happened.” What they said was: “This is a state secret.”

For uncovering the state’s dirty secrets, I was given five years and ten months in prison. We had appealed the conviction to a higher court but after the coup attempt a state of emergency was declared and the rule of the law was completely suspended.

To expect justice to be served by a judiciary under the complete control of the government would have been as naive as expecting mercy from the “mob”.

I went abroad and said that I would not return until the state of emergency was lifted and the rule of the law was restored.

Then the mob took my wife hostage. We are not the only people to face such relentlessness.

The 64-year-old mother-in-law of one of the supposed coup plotters was taken to a prison in a wheelchair. The father of another accused, who was not caught, was taken into custody as he left prayer in a mosque. The passports of wives and daughters have been confiscated and hundreds of families have been forcefully separated without trial.

These are direct violations of the principle of individual responsibility for crime.

Guilt by association allows such mob-like lawlessness prevails in a country that is a member of the Council of Europe.

It was the present government that brought the coup plotters who tried to overthrow it into the state, tasked them with cleansing its opponents and made a giant out of them.

When they had a dispute over distribution of spoils and dissolved their partnership, there remained within the state a well rooted and gargantuan parallel organisation.

Then the conflict peaked on July 15 when Frankenstein’s monster attacked its creator.

The violent coup attempt was put down because the military headquarters did not lend it support and the people took to the streets. But Erdogan has treated the event — in his own words — as “a godsend”. Using the tactics used by US senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s, he has started a witch hunt that will incarcerate all opposition.

More than 40,000 people have been taken into custody while 80,000 civil servants have been removed from their duties. Dozens of journalists have been arrested. Nearly 100 media outlets have been shut down.

Yet the rage of the government has not been quelled. Now it is taking it out on the relatives of those “witches” it did not catch.

It says: “We have your wife. Come back or she’s gone.”

But we all know that at the end of the movie the bad guys are defeated, the hostages are freed and families are reunited.

I have no doubt that this is what will happen in Turkey. Those who have made a mob out of the state will be tried. Families will get back together and celebrate the end of the witch hunt and the return of freedom, democracy and justice.

We are well aware of this and we labour to make that day come true.

Can Dündar: Turkey is “the biggest prison for journalists in the world”

Turkey should drop criminal charges against journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül