13 May 2016 | Digital Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Ukraine

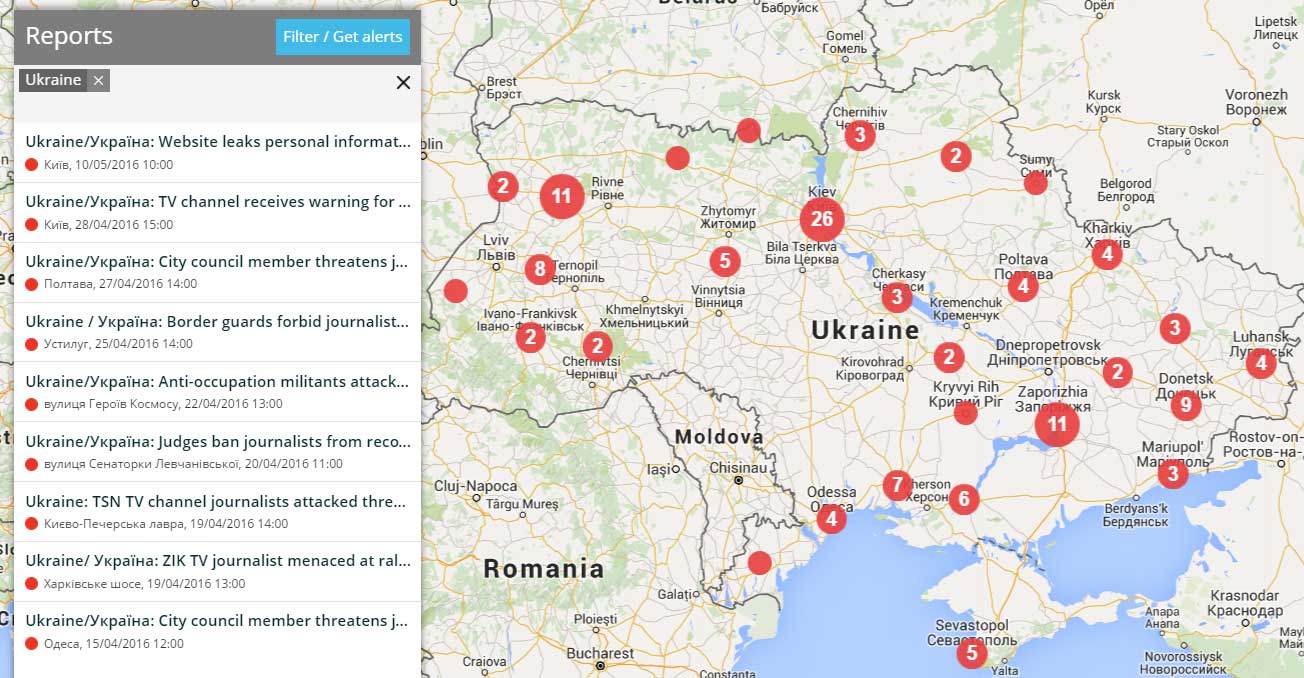

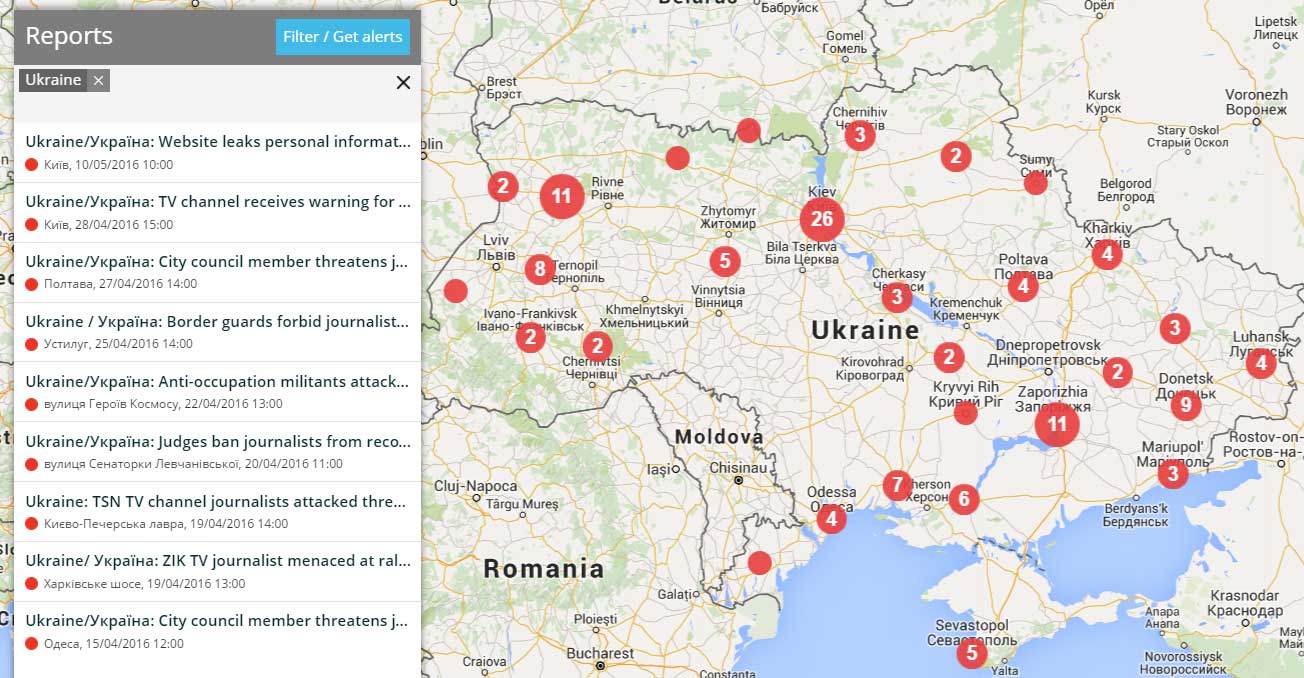

Ukraine is again at the center of an international scandal. On 10 May Ukrainian website Myrotvorets, which publishes personal data of alleged separatists, made public information about the journalists who have been accredited in the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) — the part of Donbas area beyond Ukraine’s government control.

The website, which announced on Friday 13 May that it was shutting down, leaked personal data of more than 4,000 journalists, including those working for BBC, Reuters, AFP, The Independent, Ceska televize, CNN, Bloomberg, Aljazeera, AP, Liberation, ITAR-TASS and other media.

The site published the names of the journalists, the media outlets they work for, country of origin, cell phones, email and dates of stay in the DPR.

Myrotvorets, or Peacemaker, received the data from Ukrainian hackers who had attacked DPR sites. After the data was illegally disclosed, the hackers declared a boycott and suspended their activities.

The website also accuses the journalists of co-operating with “militants of the terrorist organisation” and claims that “journalists with Russian names work for many non-Russian media (CNN? BBC? AFP?).”

Myrotvorets has long been raising concerns and criticism of Ukrainian human rights activists. Launched in the spring of 2014, it publishes the personal data of people its writers see as supporting separatism in Ukraine.

In particular, it had published the personal data of former Ukrainian lawmaker Oleh Kalashnikov and journalist Oles Buzyna. Both were murdered near their apartments shortly after the release of their information.

Breaking legislation on personal data protection and the presumption of innocence, the site has been operating for two years without any prosecution for its activities.

In April 2015, the Ukrainian parliament’s Commissioner for Human Rights Valeria Lutkovska demanded that the security service and the interior ministry block the website and prosecute those behind it. Instead, she received only threats in response.

As a result, Anton Herashchenko, the MP from the People’s Front faction and the advisor to the Ukrainian Interior Minister, who previously announced his involvement in the creation of Myrotvorets, threatened Lutkovska with dismissal. He said that operation of the website was “extremely important for the national security of Ukraine and the one, who does not understand this or attempts to hinder its operation, is either a puppet in the wrong hands or works against the national security” and the information is collected “exclusively from such open sources as social networks, blogs, online directories, news feeds”.

Lutkovska’s office of ombudsman told Mapping Media Freedom that the police launched a criminal case last year, but there are no tangible results yet and the website continues its work. The sites servers are located outside Ukraine.

In the wake of the publication of journalists’ information, Lutkovska again appealed to the interior ministry and security service aksing for the site to be blocked.

Journalists, whose personal data was published, have already received threats. Ukrainian freelance journalist Roman Stepanovych has published a threat he received via e-mail.

Stepanovych, who currently works mainly for Vice News, told Mapping Media Freedom: “I filmed in Donbas like a stringer for different news agencies like NBC, DW, Reuters and sometimes worked as a fixer for Die Ziet, CCTV, Aftenposten and many more. I am a native of Donetsk, but have always worked for the western media.“

Stepanovych, who is working outside Ukraine, said that he was considering asking police to investigate the threats when he returns to the country.

On May 11, journalists working for Ukrainian and foreign media issued a joint statement with Ukrainian and international media organisations demanding that Myrotvorets immediately take down the personal data of journalists, who had been accredited in the DPR:

“The Ukrainian and foreign journalists, who risked their lives to cover the events impartially and told what was happening in the occupied territories in Ukrainian and international media, were exposed to attack. In particular, it is thanks to their work we found out about the Vostok battalion, crimes of militant known as Motorola and other militants, supply of Russian weapons and many other important facts. These journalists gave information for a qualitative investigation into downing of MH17 flight in the summer of 2014, and their materials about senior officials of the occupied territories formed the basis of many investigative and analytical articles. We especially emphasise that accreditation does not mean and has never meant cooperation of journalists with any party to the conflict. Accreditation is a form of protection and safety of journalists.”

According to the Ukrainian and international media organisations, nearly 80 journalists were taken captive in 2014, many of whom suffered torture. Accreditation is the only, although minor, mechanism for protection of journalists from torture or captivity.

Lutkovska and the journalists also appealed to Ukrainian authorities asking for a launch of criminal proceedings. On the same day, the address of the European Union’s ambassador to the Ukraine, Jan Tombinski, was released. Tombinski said that publication of the journalists’ leaked personal data violated the best international practices and Ukrainian legislation. He urged Ukrainian authorities “to help ensure that this content is no longer published“.

In response, Anton Herashchenko posted on his Facebook page: “Currently, Ukraine has no lawful methods to block harmful content and has no principles of defining which content is illegal and harmful and which is not. Ukraine has also no technical possibility to block any content on the internet.”

On May 11, the Kyiv prosecutor’s office opened criminal proceeding under Article 171 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (Preclusion of legal professional activities of journalists).

12 May 2016 | mobile, News and features

Facebook made headlines this week over allegations by former staff that the site tampers with its “what’s trending” algorithm to remove and suppress conservative viewpoints while giving priority to liberal causes.

The news isn’t likely to shock many people. Attempts to control social media activity have been rife since Facebook and Twitter launched in 2006. We are outraged when political leaders ban access to social media, or when users face arrest or the threat of violence for their posts. But it is less clear cut when social media companies remove content they deem in breach of their terms and conditions, or move to suspend or ban users they deem undesirable.

“Legally we have no right to be heard on these platforms, and that’s the problem,” Jillian C. York, director for international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, tells Index on Censorship. “As social media companies become bigger and have an increasingly outsized influence in our lives, societies, businesses and even on journalism, we have to think outside of the law box.”

Transparency rather than regulation may be the answer.

Back in November 2015, York co-founded Online Censorship, a user-generated platform to document content takedowns on six social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Flickr, Google+ and YouTube), to address how these sites moderate user-generated content and how free expression is affected online.

Back in November 2015, York co-founded Online Censorship, a user-generated platform to document content takedowns on six social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Flickr, Google+ and YouTube), to address how these sites moderate user-generated content and how free expression is affected online.

Online Censorship’s first report, released in March 2016, stated: “In the United States (where all of the companies covered in this report are headquartered), social media companies generally reserve the right to determine what content they will host, and they do not consider their policies to constitute censorship. We challenge this assertion, and examine how their policies (and the enforcement thereof) may have a chilling effect on freedom of expression.”

The report found that Facebook is by far the most censorious platform. Of 119 incidents, 25 were related to nudity and 16 were due to the user having a false name. Further down the list were content removed on grounds of hate speech (6 reports) and harassment (2).

“I’ve been talking with these companies for a long time, and Facebook is open to the conversation, even if they haven’t really budged on policies,” says York. If policies are to change and freedom of expression online strengthened, “we have to keep the pressure on companies and have a public conversation about what we want from social media”.

Critics of York’s point of view could say if we aren’t happy with the platform, we can always delete our accounts. But it may not be so easy.

Recently, York found herself banned from Facebook for sharing a breast cancer campaign. “Facebook has very discriminatory policies toward the female body and, as a result, we see a lot of takedowns around that kind of content,” she explains.

Even though York’s Facebook ban only lasted one day, it proved to be a major inconvenience. “I couldn’t use my Facebook page, but I also couldn’t use Spotify or comment on Huffington Post articles,” says York. “Facebook isn’t just a social media platform anymore, it’s essentially an authorisation key for half the web.”

For businesses or organisations that rely on social media on a daily basis, the consequences of a ban could be even greater.

Facebook can even influence elections and shape society. “Lebanon is a great example of this, because just about every political party harbours war criminals but only Hezbollah is banned from Facebook,” says York. “I’m not in favour of Hezbollah, but I’m also not in favour of its competitors, and what we have here is Facebook censors meddling in local politics.”

York’s colleague Matthew Stender, project strategist at Online Censorship, takes the point further. “When we’re seeing Facebook host presidential debates, and Mark Zuckerberg running around Beijing or sitting down with Angela Merkel, we know it isn’t just looking to fulfil a responsibility to its shareholders,” he tells Index on Censorship. “It’s taking a much stronger and more nuanced role in public life.”

It is for this reason that we should be concerned by content moderators. Worryingly, they often find themselves dealing with issues they have no expertise in. A lot of content takedown reported to Online Censorship is anti-terrorist content mistaken for terrorist content. “It potentially discourages those very people who are going to be speaking out against terrorism,” says York.

Facebook has 1.5 billion users, so small teams of poorly paid content moderators simply cannot give appropriate consideration to all flagged content against the secretive terms and conditions laid out by social media companies. The result is arbitrary and knee-jerk censorship.

“I have sympathy for the content moderators because they’re looking at this content in a split second and making a judgement very, very quickly as to whether it should remain up or not,” says York. “It’s a recipe for disaster as its completely not scalable and these people don’t have expertise on things like terrorism, and when they’re taking down.”

Content moderators — mainly based in Dublin, but often outsourced to places like the Philippines and Morocco — aren’t usually full-time staff, and so don’t have the same investment in the company. “What is to stop them from instituting their own biases in the content moderation practices?” asks York.

One development Online Censorship would like to see is Facebook making public its content moderation guidelines. In the meantime,the project will continue to strike at transparency by providing crowdsourced transparency to allow people to better understand what these platforms want from us.

These efforts are about getting users to rethink the relationship they have with social media platforms, say York. “Many treat these spaces as public, even though they are not and so it’s a very, very harsh awakening when they do experience a takedown for the first time.”

11 May 2016 | About Index, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

Journalists Erdem Gül and Can Dündar in November 2015 (Photo: Bianet)

The sentencing of journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül to years in prison for sharing state secrets underscores how Turkey’s government is crushing critical voices. The trial follows Dündar and Gül’s investigative reporting on links between the Turkish intelligence services and arms to Islamist groups in Syria. Dundar has been sentenced to five years and 10 months, and Gul to five years.

Index on Censorship condemns this clearly political ruling and calls for an end to judicial harassment of Dündar, Gül and all journalists in the country. The country’s drastic decline has been well documented by Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project and Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index. The closure of the seized Zaman newspaper group is only one recent example of the government’s draconian attitude toward independent media.

“The Turkish government is now resorting to locking up journalists like Dündar and Gül, who sought to reveal information of public interest, something journalists around the world do every day. Yet they are paying a heavy price. The sentencing is an example of an ongoing decline in Turkey’s attitude to freedom. It has entered a new dark age where the truth is forbidden and even a hint of dissent is not tolerated,” Melody Patry, senior advocacy officer, Index on Censorship, said.

From the outset of the case in November 2015, Dündar, the editor-in-chief of daily newspaper Cumhuriyet, and Gül, head of the paper’s Ankara bureau, were accused of spying and terrorism after the paper published evidence in May 2015 of Turkey’s intelligence services’ involvement in Syria’s civil war. In the wake of the revelations, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, president of Turkey, publicly declared that Dundar and his paper “will pay for this”.

Dündar nearly paid with his life. Shortly before a court issued his sentence, a man identified in Daily Sabah as Murat Şahin attempted to shoot the editor, but was thwarted by the intervention of Dundar’s wife and an onlooker.

Both Dündar and Gül are free on bail as they appeal their sentences.

11 May 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Letters

E. Belit Sağ is a Turkish activist and artist

It was my intention for a long time to publish a statement about the censorship of my video Ayhan and me (2016), part of the group exhibition Post-Peace that was censored by Akbank Sanat. When the exhibition was censored, I wanted to prioritise the group statement of the collaborators and artists of the exhibition. The group statement is out, and it’s now my turn. I would like this statement to be seen as a contribution to the statements made by Katia Krupennikova, the curator of the show; the jury of the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015; Anonymous Stateless Immigrants Movement; and the artist and contributors of the exhibition Post-Peace. With this statement, I aim to share my own experience.

I am the only artist from Turkey that was supposed to take part in the group exhibition Post-Peace. My initial proposal was specifically about Turkey. This proposal went through a censorship process starting months before the originally planned opening date. I’d like to share my experience with the hope that it will shed a little bit of light on the censorship that of the exhibition itself and the problem of censorship in the art field more generally.

The group exhibition Post-Peace was initially planned to take place in Amsterdam. I was invited by the curator at this early stage. Later on, with this exhibition concept, Katia Krupennikova applied for and won the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015. The exhibition moved from Amsterdam to Istanbul. In one of the talks Katia had with Akbank Sanat managers in November 2015, she mentioned to them my proposal. They told Katia that the political situation in Turkey is tense and that they can not commission the proposed work. Katia asked for an official statement from the director of Akbank Sanat, Derya Bigalı. She didn’t receive a reply. I met Katia when she came back to Amsterdam. We wrote together to Zeynep Arınç from Akbank Sanat, with whom Katia has been in contact throughout the process. We asked for a formal rejection letter from the director, explaining the reasons for their decision. Zeynep Arınç replied to our email informally telling Katia that Akbank Sanat can not commission this work.

My initial work proposal, censored by Akbank Sanat, was about Ayhan Çarkın. Ayhan Çarkın was part of JITEM, an unofficial paramilitary wing of the Turkish Security Forces active in mass executions of the Kurdish population in the 1990s. As a part of the deep state and JITEM, Ayhan Çarkın confessed in 2011 that he led operations that killed over 1000 Kurdish people during the 1990s. These confessions were made on television, and videos from those confessions are accessible on Youtube. The work I was planning to make was about Ayhan Çarkın’s personal transformation, how historical reality is constructed, and how to think about the term ‘evil’. This work, which was only a written proposal at that point, was censored by Akbank Sanat, even though it was part of the curator’s exhibition concept from the very beginning, and was chosen by an international jury as part of the exhibition for Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015.

This was the first time something like this had happened to me. Instead of leaving the exhibition, Katia and I came up with a proposal for a new work. The new work was going to talk about the censorship of my previous proposal, as well as the politics of images of war in Turkey. Akbank Sanat requested to see the script of this new work. Katia didn’t respond to this request, and I told her that I’m not in favour of showing the script, due to Akbank Sanat’s attitude up till that point. Consequently, we asked the founder of the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition, curator Başak Şenova, for her opinion on this issue. At first she supported us, but after she consulted with Akbank Sanat she told us that the refusal by Akbank Sanat is understandable. To be honest these reactions made me feel alone. Turkey is really going through a tough period, and I started questioning why, as an artist, I was putting the whole institution at risk.

In December before I started producing my second proposal I realised that I did not feel comfortable with accepting the situation as it was. I decided to make the censorship public, by writing a letter and sending it to the press. I met with Katia and we started writing an email explaining the situation to the jury. In mid-January, before we finalised the letter, Katia told me that she talked to Akbank Sanat and they agreed to the new proposal and no longer demanded to see the script in advance. I started making the video. I got in contact with Siyah Bant, a group that deals with censorship in the field of art in Turkey. I got a lot of support from them, which helped against the feeling of isolation such censorship cases cause. Also, we started thinking about ways to deal with this specific case. The final video took shape as a result of this process. I believe watching the video complements this statement.

Ayhan ve ben (Ayhan and me) from belit on Vimeo.

The video was finalised on 23 February, and Katia Krupennikova presented all the works to Akbank Sanat for a technical check on the same day. The exhibition was supposed to open on 1 March, and it was cancelled/censored on 25 February. There was no exhibition announcement on Akbank Sanat’s website or social media accounts, or there was any exhibition poster at Akbank Sanat’s space at any point. This makes me think that Akbank Sanat has been considering this decision for a long time, but didn’t communicate it to the curator or any other contributor of the show.

I don’t know and will never get definite confirmation whether the cancellation of Post-Peace was related to the content of my work or not. However, this does not change what happened. Together with Siyah Bant, we prepared a press release explaining the censorship prior to the cancellation of the exhibition. Even if the exhibition had not been cancelled, I was planning to publicise my experience of Akbank Sanat’s censorship.

In the 90s, Akbank Sanat hosted a painting exhibition by Kenan Evren. Kenan Evren is the leader of the 1980 coup d’etat in Turkey. Akbank Sanat has had several censorship cases in its history. Akbank Sanat gave Kenan Evren the possibility to exhibit his work as an “artist”, without questioning his leading role in the 1980 coup, from which the country still suffers. Akbank Sanat has never taken responsibility for this exhibition nor the role they took in it and what it means for Turkey. I do not believe that Akbank Sanat has or aims to acquire the ethical and conceptual capacity to host any exhibitions. The Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition that they have sponsored for the past four years is an important award in the international art world, which gives them a prestige they do not deserve.

At this point I have a number of questions to ask:

– Why does Akbank Sanat have the right to bypass the jury of Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015 and the originally accepted plan of the exhibition? As mentioned in Başak Şenova’s statement following the cancellation: “Afterwards, Akbank Sanat unquestioningly implements all aspects of the exhibition”

– How does Akbank Sanat position itself in relation to the jury of the competition, the founding curator, the curator, and the artists of the exhibition?

– Why didn’t Akbank Sanat discuss the possibility of cancelling the exhibition together with the curator, the artists and the jury prior to the cancellation? Why does Akbank Sanat take decisions from the top, thereby marginalising the contributors and blocking their participation in decision-making mechanisms concerning the very exhibition they have been commissioned to make?

Institutions like Akbank Sanat will not admit that they censored the content of any exhibition, and will not take responsibility for the situation. These institutions interfere with cultural content due to their connections to corporations and banks, allied with oppressive government policies. This paves the way for normalising censorship and abusing the political situation of the country as an excuse, as in the text explaining the cancellation by the director of Akbank Sanat (“Turkey is still reeling from their emotional aftershocks and remains in a period of mourning.”).

I believe we need to expose these government-allied mentalities and structures over and over again. Institutions like Akbank Sanat can continue their activities because every time they censor the cultural arena they get away with it; their acts are not revealed, they are not held accountable, and they continue to receive support. Letting this happen deserts the fields of culture and art, and distances them from the struggles going on in the country. At the same time, this acceptance and silence obstructs those people and institutions that bravely resist, and further restricts already shrinking zones of freedom. We, as cultural and art workers, can counter this by refusing to accept the silencing of artistic expression.

Any cultural and art worker who is ignorant of the ongoing oppression in Turkey, who does not call censorship by its name, who does not see or fails to recognise the ongoing massacres in Kurdish lands becomes part of this oppressive structure. I have channels to speak out, I do not want to intimidate people who don’t have access to such channels, or who have to stay silent in order to avoid risking their lives. It is exactly for this reason, that we have to speak out en masse. I also think that ‘speaking out’ can happen in a variety of ways, just as acts of resistance do.

Although I have a hard time believing it myself, almost everyone I met in Cizre (a Kurdish town inside Turkey bordering Syria) in 2015, has either been killed or else left Cizre in order to stay alive. I owe this statement to the people I met in Cizre. Many other Kurdish towns and cities have suffered from or are currently undergoing similar attacks by Turkish State security forces. Every struggle in this region is connected, even though some might want to separate them. The one sharp difference is that some people get censored and others get killed in this country. Exactly because of this, we, the ones who get censored, need to keep ourselves connected to other resistances and realise of our privilege.

With this letter I wish to show solidarity with those working in the fields of culture and art who have already experienced or might experience similar censorships. My statement aims to express that we do not have to bear those abuses alone, with the hope that more of us will be able to speak up, and the hope that we can act collectively.