Update: On 13 July 2017 the Chinese Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, jailed for his pro-democracy work, died in hospital aged 61.

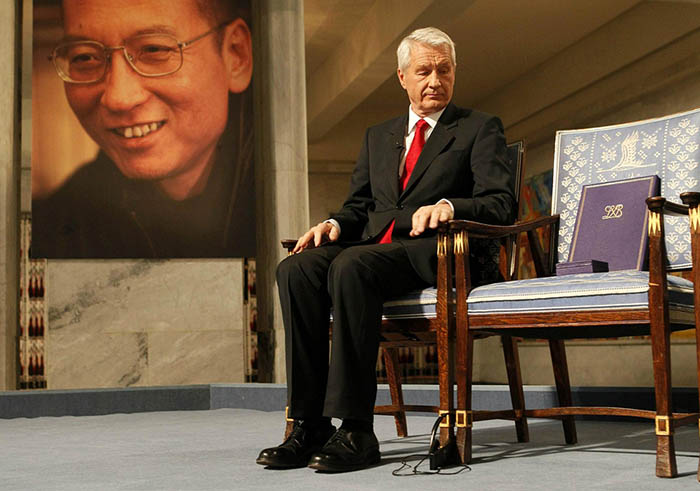

When Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, Chinese authorities were sent into a state of panic. Liu had been in prison since 2009, following the release of Charter 08, a pamphlet he co-wrote that called for greater democratic freedoms. As the world’s attention was on China and on Liu, all references to Liu and the prize were blocked online and off. Then his wife and many of his acquaintances were detained in an attempt to stop them from going to Oslo and collecting it on his behalf. At the ceremony itself, an empty chair became a stark reminder of his absence and soon the words “empty chair” started to race through the internet. These too were blocked.

Liu has since remained in prison and efforts to stamp out his name continue. But last week he once again made headlines following his release from prison on health grounds. At the time of writing, reports say Liu, who is suffering from late-stage liver cancer, is close to death. For free speech advocates around the world, this news is saddening. No figure has come to represent the fight for Chinese democracy as much as Liu Xiaobo.

Born in 1955 in Jilin province in northeast China, the son of two teachers, Liu went on to become a writer, activist and academic. It was while teaching at Columbia’s Barnard College in New York in 1989 that the Tiananmen Square protests broke out. Liu decided to return to China to take part in them on their final, fateful day. This led to his arrest and imprisonment, the first of four times.

Liu was shunned by China’s academic community when he left prison two years later, but that did not silence him and he continued to build on his reputation within China as an outspoken critic of the Communist Party. He also started a tradition of writing poems about Tiananmen every year to mark the anniversary – a powerful reminder that the government does not have a monopoly on memory.

For Liu the internet was a lifeline. He described it as “God’s gift to the Chinese people” in an essay that was published in Index on Censorship magazine in 2006. The web became his primary portal to publish his thoughts to the outside world and to reach audiences when traditional forms of media were out of bounds. Liu wrote that “the effect of the internet in improving the state of free expression in China cannot be underestimated”.

Liu’s influence peaked in December 2008 with Charter 08, a document modelled on Václav Havel’s Charter 77, written in Communist Czechoslovakia 30 years earlier. The document outlines the basic principles and fundamental rights that should govern China’s political landscape. Over 350 intellectuals and activists initially signed it, with a further 10,000 people including academics, journalists and businessmen adding their names to it upon its released. The government’s reaction to Charter 08 was swift and harsh. Liu was initially arrested two days prior to its official publication and later charged with 11 years in prison for incitement to subversion, during a trial in which he said he had no enemies. Index has repeatedly called for his release.

Isabel Hilton, a leading expert on China, told Index back in 2010 that “when the history of free expression and freedom of ideas is written, he and the other signatories of Charter 08 will be remembered as courageous citizens who sought the best for their country”.

In an interview Liu gave prior to his arrest, he said: “The way I see it, people like me live in two prisons in China. You come out of the small, fenced-in prison, only to enter the bigger, fenceless prison of society.” Since Liu’s arrest almost a decade ago, China has continued to change at breakneck speed. When it comes to human rights and free speech, sadly this change has been predominantly for the worse. The bigger, fenceless prison that Liu spoke of is today a lot more closed and draconian. China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, has overseen a huge crackdown on dissent. And the internet, God’s gift to China, is more regulated that ever before. Even seemingly innocent entertainment channels are frequently shut down, such as Kuaishou, a video-sharing site, which Index on Censorship reported on in its most recent issue.

Despite this, people continue to fight for greater freedom and rights in China, exploiting loopholes online as and when they can, and showing remarkable courage in the face of extreme adversity. The role of Liu in setting an example and providing inspiration cannot be underplayed. Liu’s Nobel chair might still be empty, but he is never forgotten, nor will he ever be.

Read more:

Liu Xiaobo’s article on the power of the internet in full

A poem by Liu translated for Index on Censorship magazine

Esteemed writer Ma Jian’s response to the Nobel Peace Prize and thoughts on Liu

The government ban of words related to Liu Xiaobo and the Nobel Peace Prize