21 Feb 2017 | Awards, Press Releases

- 受邀之评判员包括演员Noma Dumezweni; 以及Vanity Fair前主编Tina Brown

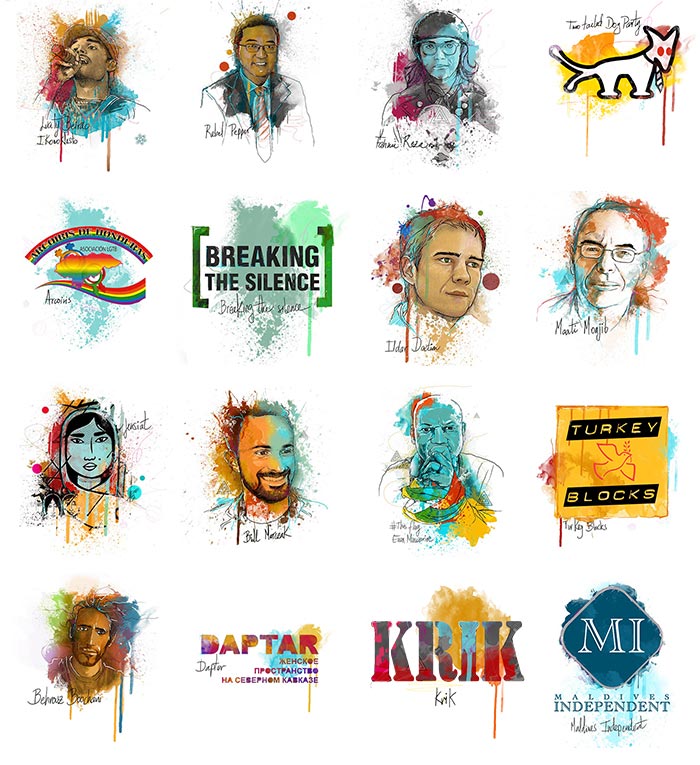

- 被列入最终候选名单的言论自由活动家一共有十六人:

此奖项之最终候选者包括被津巴布韦当局拘扣的#ThisFlag活动家,一位来自伊朗在澳洲被拘留的寻求庇护者,一位中国大陆的漫画家以及一位来自俄罗斯的人权活动家。Index on Censorship 为了奖赏在世界各地与种种审查制度搏斗多年的记者以及艺术家而拟定了这个候选名单。特别值得一提的是,被大众提名的言论自由活动家一共有四百位之多。这十六位候选者为了争取言论自由经常遭受当地政府的迫害, 有的甚至面临生命危险。

Index on Censorship 之活动总裁 Jodie Ginsberg 说过:“候选者的艺术作品无论大小,都能够在争取言论自由这方面引发显著的正面效果。此奖项认可了这十六位为了争取言论自由遭受种种迫害的最终候选者。”

2017年审查指数之言论自由奖再分为四种奖项: 艺术奖,言论自由运动奖,电子活动奖以及新闻业奖。

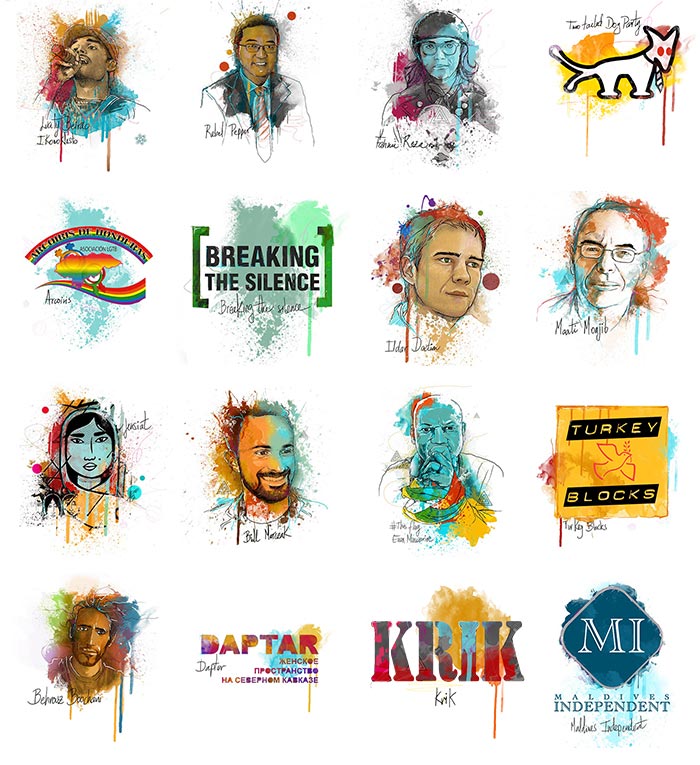

此奖最终候选者包括来自津巴布韦的 Evan Mawarire。令Evan大失所望的当地政府促使他组织#ThisFlag这项活动。一名来自伊朗库尔德族的记者Behrouz Boochani ,也是最终候选者之一。 他记载了在巴布亚新几内亚被拘留的寻求庇护者之生活点滴。候选者当中有一位来自中国大陆的漫画家,他就是笔名为“变态辣椒” 的王立铭,以其政治讽刺漫画而闻名。 其他的候选者包括首位因参与非法集会而被监禁的俄罗斯行动主义分子, Ildar Dadin, 应付达吉斯坦妇女所面临的种种压迫之组织,Daptar, 一群塞维利亚记者为了举报贪污罪行而成立的 “KRIK”组织 , 一个为讽刺匈牙利政而成立的 “两位党”,一个称为“Arcoiris”的同志人权组织(此组织的其中六位行动主义分子因给予当地同性恋社区资助而被谋杀),一位以说唱乐揭发安哥拉的政治腐败的歌手,Luaty Beirão以及一个揭露高层贪污罪行的网站,“Maldives Independent”。

第十七度审查指数 (Index on Censorship) 之言论自由奖受邀之评判员包括哈利波特女演员Noma Dumezweni,来自Hillsborough的律师Caiolfhionn Gallagher, Vanity Fair前主编Tina Brown,Superflux 创办者Anab Jain以及音乐制作人Stephen Budd。在哈利波特 · 被诅咒的孩子里扮演Hermione的Dumezweni今年被列入Evening Standard Theatre Award最佳女演员之候选名单。对于审查指数 (Index on Censorship) 之言论自由奖,她表示:“言论自由在挑赞世界观的过程中扮演十分重要的角色。“

此言论自由奖之组办当局将在四月十九日公布审查指数 (Index on Censorship) 之言论自由奖的得奖者,而这些得奖者将会获得在交际方面的培训以及定制支持和帮助以维持他们的艺术活动。2016年审查指数 (Index on Censorship) 之言论自由电子活动奖得奖者Charlie Smith(GreatFire 组织)表示:“GreatFire这个组织一向都是匿名地独自进行活动,获得审查指数 (Index on Censorship)电子活动奖以后,我们开始与一些活动主义分子结成同志关系。Index时时刻刻都会给予我们组织运作及策略方面的辅助。”

今年审查指数 (Index on Censorship) 之言论自由奖的赞助家包括SAGE出版社,谷歌,沃达丰(Vodafone),CNN, VICE News, Doughty Street Chambers以及Psiphon与Gorkana。Sebastián Bravo Guerrero 绘画候选者的插图。

- 审查指数 (Index on Censorship)是一个出版在世界各地受审查之作品的非牟利组织。

- 以下是有关审查指数 (Index on Censorship) 之言论自由奖之候选者的资料:

- 此言论自由奖之组办当局将在四月十九日于The Unicorn Theatre, London公布审查指数 (Index on Censorship) 之言论自由奖的得奖者。

- 欲知详情,或者欲与候选者安排采访,请联络Sean Gallagher(0207 963 7262/[email protected])。若您欲知有关审查指数 (Index on Censorship) 之言论自由奖之候选者的资料,请浏览indexoncensorship.org/indexawards2017。

20 Feb 2017 | News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship has recruited a new youth board to sit until June 2017. The group is made up of young students, journalists and legal professionals from countries including India, Hungary and the Republic of Ireland.

Each month, board members meet online to discuss freedom of expression issues around the world and complete an assignment that grows from that discussion. For their first task the board were asked to write a short bio and take a photo of themselves holding a quote that reflects their belief in free speech.

Fionnuala McRedmond – Dublin

Fionnuala McRedmond – Dublin

I graduated last June from the University of Cambridge with a degree in classics. I am now studying for a MSc in political theory at the London School of Economics. I was an active student journalist during my time at Cambridge, and it was there that I first developed an interest in the struggles of censorship and speech across the globe. The propensity for governments to censor speech and ideas is not a modern phenomenon. In ancient Rome book burning was not unheard of, and Cicero once expressed the all too familiar idea: “it is not permitted to say what one thinks… it is obviously permitted to keep silent.” Then, as much as now, free speech was the cornerstone of a healthy society. And then, as much as now, speech was censored by tyrannical power. I am particularly interested in the relationship between censorship and identity. In the past, and even more so now, people have been denied the right to share their words and ideas on the basis of ethnic, religious and political identity. Work by groups like Index on Censorship is crucial in protecting people’s right to speak, no matter who they are. I hope to better understand and develop these ideas with the Index on Censorship youth board.

Júlia Bakó – Budapest

Júlia Bakó – Budapest

I am a Hungarian journalist, student and activist currently living in Budapest. After finishing my first degree in journalism, I have started studying international relations.

As a journalist and as someone who is deeply committed to human rights I am naturally drawn to freedom of expression and freedom of press issues. During the last couple of years I have worked with several NGOs and other organisations like Transparency International, Amnesty International, OSCE and Atlatszo.hu. I have dealt with corruption cases as an investigative journalist, I have studied human rights monitoring and – partly because of my studies, but mostly because of my personal interest and commitment – I have tried to explore freedom of expression and other issues not just in my own country, but all over the world, to find patterns, similarities and possible measures that could be taken either on a national or international level.

The quote I chose about freedom of expression says something what we sometimes tend to forget about. Being able to express our own opinions, however right they may seem to us, should never stop us from fighting for the rights of others to be able to act the same way, even though their opinions seem fundamentally different sometimes. Granting the chance to express opinions we do not agree with is what is able to create the diversity of thought, the debate about social issues and with that democracy itself.

Samuel Earle – Paris

Samuel Earle – Paris

I currently live in Paris, where I am a freelance writer and English teacher.

I became interested in freedom of expression while studying politics at university – first at undergraduate and then at MSc level – and that continues today through my interest in journalism. What’s clear to me is that although freedom of expression is always valuable, the challenges it faces globally are never the same.

In the west, I think there is a complacency concerning freedom of expression: that stopping censorship is assumed to be enough. But I believe that in societies as unequal as our own, and where market forces reign, the value of freedom of expression can be diminished – as shown, for example, by the fake-news phenomenon.

Samuel Rowe – London

Samuel Rowe – London

I am currently a postgraduate law student, having studied literature as an undergraduate in the UK and the USA. I hope to become a public law barrister, specialising in media and information law and human rights. Like the character in Kurt Vonnegut’s Hocus Pocus, I believe that the right to freedom of speech is innate. It is not a commodity; it is not something to be bargained with. My interest in issues surrounding freedom of speech directed my undergraduate dissertation, which focused on the western surveillance state. This sort of covert action can have the effect of creating an environment of self-censorship, and often has a disproportionate impact on marginalised communities. I looked at methods of resistance (of which there are many) to see how groups maintained freedom of speech under the gaze of the state. The suppression of freedom of speech is hardly a novel phenomenon and mass surveillance is just one way in which it is currently under threat. From White House officials calling disagreeable information “fake news” to irresponsible no platforming in universities, this is an era in which the limits and value of freedom of speech are being questioned. I believe that without freedom of speech, there can be no full interrogation of the evils which face us. And without interrogation, we risk losing sight of the full scope those evils might pose.

Tarun Krishnakumar – New Delhi

Tarun Krishnakumar – New Delhi

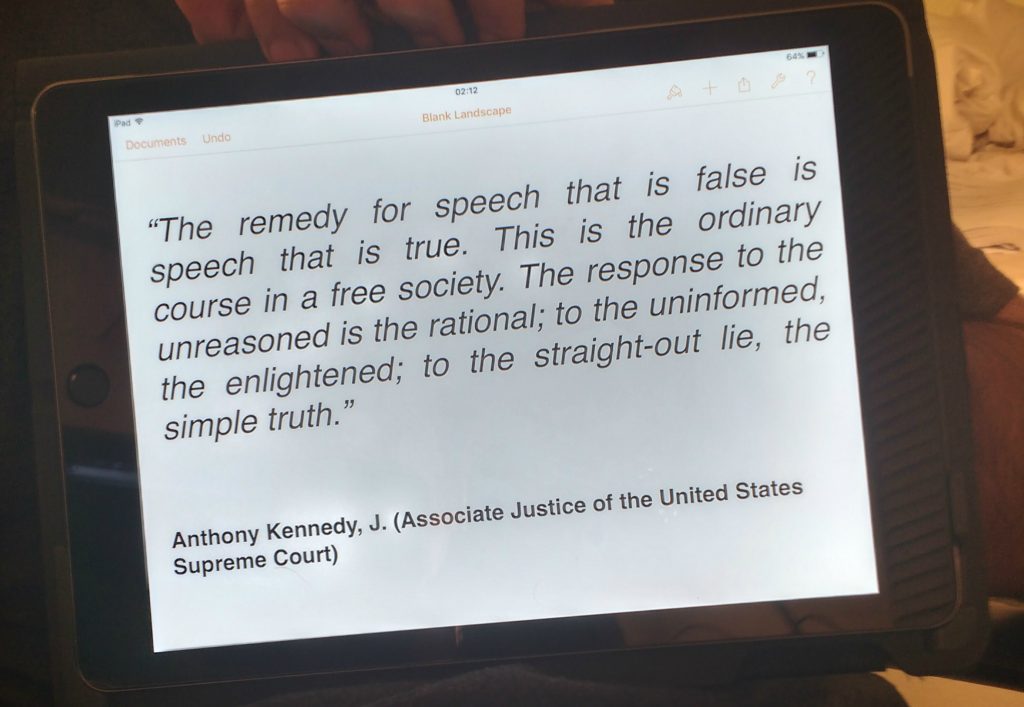

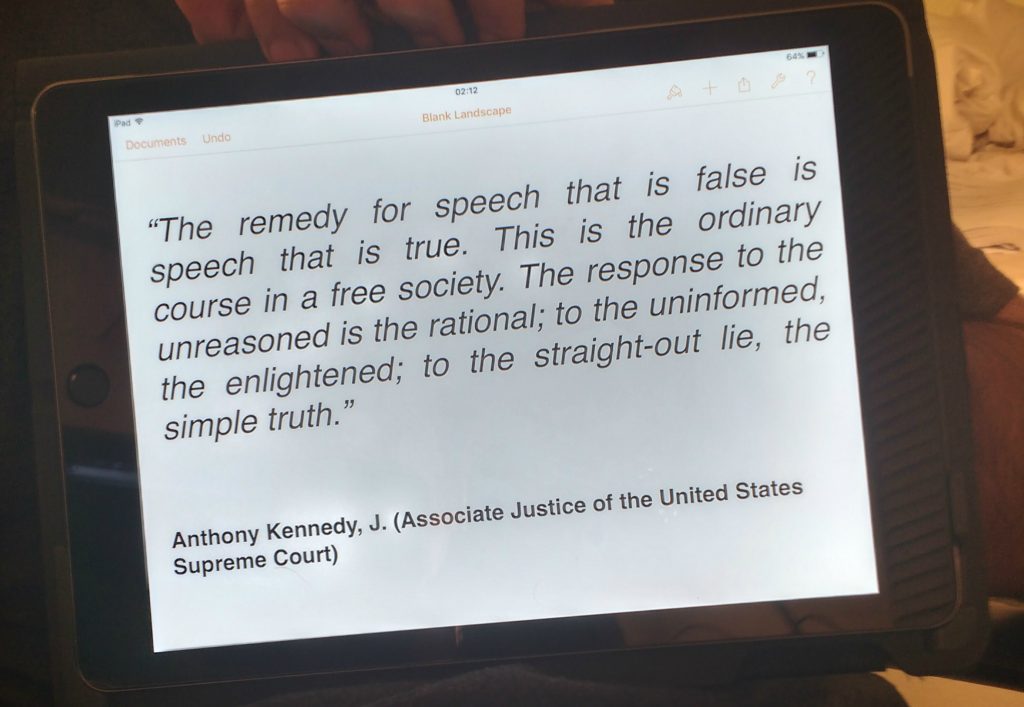

In recent times, there has been much concern expressed about the proliferation of “fake” news online and the impact it can have on democratic processes, politics and the public at large. These concerns have stirred various stakeholders – including governments, news media and internet intermediaries – into action. For instance, the German government recently declared fake news from Russia to be a significant threat to its upcoming elections. In a similar vein, internet giants like Google and Facebook – likely in the wake of unfavourable political outcomes – have been clamouring to show that they are willing to clamp down on content that is false or misleading.

In response to these developments, the quote I’ve selected manifests what, I feel, should be the appropriate response to fake speech: more “non-fake” speech – and not more regulation. While many justifications to clamp down on fake news may be well-intentioned, the history of regulating speech has shown us that inserting an intermediary into a conversation creates unintended and harmful consequences for free speech. Often this manifests as overt censorship while, in other cases, it is the creation of private arbiters of what may or may not be said on a platform – a more covert and creeping harm. Given the subjectivity in judging what news is “fake”, the debate also presents an excuse for regimes to tighten existing censorship controls or establish new ones.

The internet has given everyone an opportunity to have an equal say. This must be preserved at all costs. Fake news must be countered not through bans, blocking or regulation but by targeting the societal information asymmetries that allow it to flourish and creating conditions that facilitate society to produce more speech that is not “fake”. Policy efforts should focus on educating readers and providing them the tools to judge content for themselves – thereby minimising the effect of false or misleading content. For this, what is necessary is a culture of being exposed to a balanced diet of diverse content. When governments peddle nationalistic, religious, or political rhetoric in educational curricula and skew facts, little do they realise that they are creating the very conditions that allow “fake” news to flourish and have the harmful impacts that they complain of.

Sophia Smith-Galer – London

Sophia Smith-Galer – London

I’m a MA student studying broadcast journalism at City University in London. I studied Spanish and Arabic previously at Durham University and I’m particularly interested in how artists and writers overcome challenges to their freedom of expression in Latin America and the Middle East. As a singer I have always been intrigued by the imagery of a caged bird that sings despite its entrapment; Charlotte Bronte instead uses this metaphor to show how independent Jane Eyre has become by the end of the eponymous novel. Humans have always connected birds with freedom, or lack of – just look at Twitter’s logo – and so the quote really resonated with me.

Freedom of expression is particularly important to me as several countries that speak both of the languages I have dedicated years of study to continue to be plagued by tyrants and censors. I’m particularly interested addressing censorship in Latin America and the Middle East, especially with regard to the arts, as I’m also a classical singer and keen art historian.

Constantin Eckner – St Andrews

Constantin Eckner – St Andrews

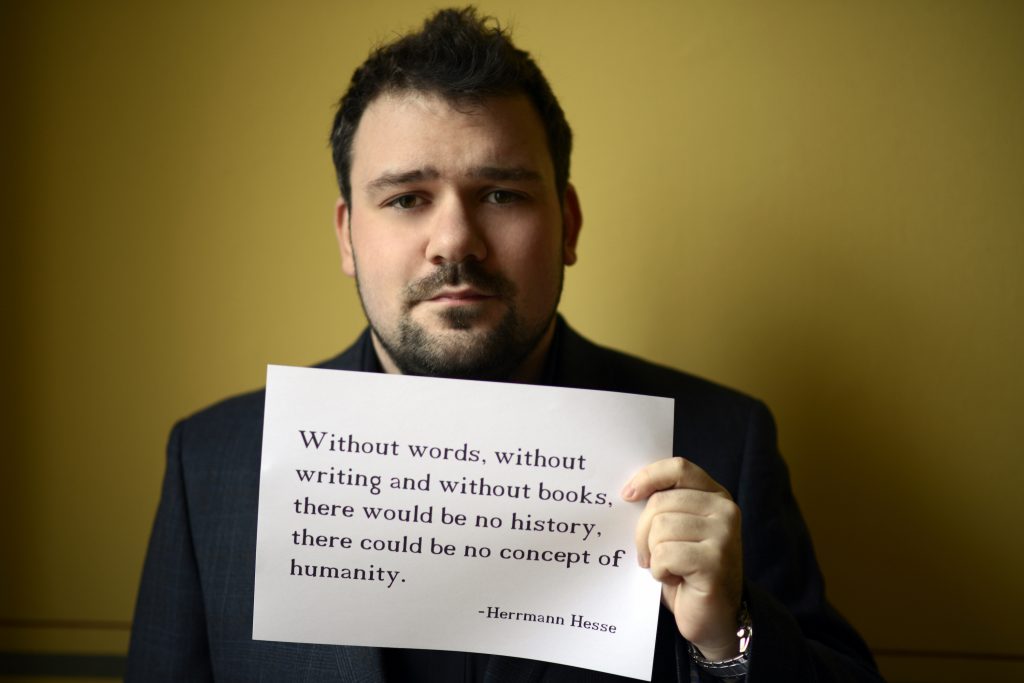

I am originally from Germany. I graduated from University of St Andrews with an MA degree in modern history. Currently, I am a PhD candidate specialising in human rights, asylum policy and the history of migration. Moreover, I have worked as a writer and journalist since I was 17 years old, covering a variety of topics over the years. Longer stays in cities like Budapest and Istanbul have raised my awareness for pressures exerted upon freedom of expression.

I chose this particular quote, because Hermann Hesse emphasised the importance of the written word and how it had an impact on the concept of humanity. In his time, Hesse was conscious that without writing it was not possible to express thoughts and spread ideas. Therefore, all those who fought the existence of the written word threatened humanity which was a frightening thought for a humanist like Hesse.

In a perfect world, every human being would live without fear of state censorship and potentially facing repercussions for the words they write—or for the pictures they draw, for the photos they shoot, for music they play.

Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm

Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm

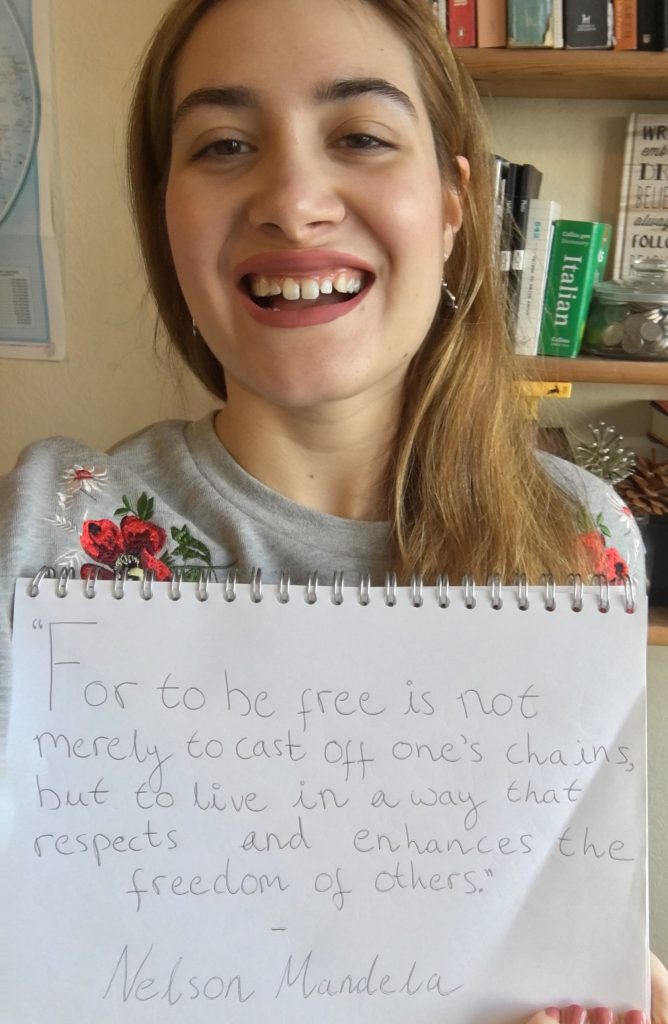

I’m half Brazilian and half Czech, raised in Sweden, but currently living in London where I work in communications for a mental health charity. I‘m also a Latin America correspondent for the International Press Foundation (IPF), a platform where young journalists get to write about stories that matter the most to them. It was during my time at Kingston University, studying journalism and French, when my interest in censorship and freedom of expression first emerged.

During my undergraduate studies I learned how important a free press is for a working democracy. It is a platform bringing together multiple voices, by sharing news, ideas and holding those in power to account. However, many journalists around the world suffer repression for simply doing their job and for using their right to free speech.

For me, Nelson Mandela‘s quote represents the importance of respecting and listening to each other, even with different views, but also highlighting the voices of those who are forced into silence.

Interviewing journalists from Venezuela and Pakistan, who face these types of constraints, has made me more engaged in sharing stories concerning freedom of expression, not only by journalists, but also by artists and activists. In the future, as a journalist, I want to focus on freedom of expression and by being part of the youth advisory board, I will be able to expand my knowledge and have great conversations with other young people who are passionate for justice and social change.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”More from the youth advisory board” category_id=”6514″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Feb 2017 | Awards, China, Digital Freedom, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

GreatFire are the 2016 Digital Activism Fellow

The 2016 Digital Activism Fellow GreatFire is a collective of anonymous individuals using technology to combat China’s draconian internet censorship regime. Charlie Smith answers questions about recent developments of China’s Great Firewall.

Index: The Chinese government warned in December that its controls on the internet are necessary to prevent foreign powers from “destabilising the state”. Would Great Fire be considered to be associated with such powers? What would be the consequences of this?

Smith: I don’t think the Chinese authorities fully understand how the internet works. They have this great image in their mind of creating “cyber sovereignty” but this is an impossible task. The internet by nature is international. Information is exchanged across borders. So, yes, foreign powers are destabilising China’s internet every minute. In the opinion of the Chinese authorities, I guess this happens every time somebody says “Xi Jinping is a totalitarian despot” or shares a photo of the great leader with his pants too high.

But even if the authorities were able to establish what they think is “cyber sovereignty”, they would quickly find that many Chinese also like saying nasty things about Xi Dada.

Index: Why do you think the latest crackdown on VPNs, requiring government registration for all VPNs based in China, is not as serious as it has been made out to be? Do you think it will make any difference to the way circumvention tools operate?

Smith: It is normal that the authorities ask that telecoms companies check to see who is using their services. There are a lot of cheap domestic VPN providers – some of whom probably do not have the interests of Chinese consumers at heart. It’s a good thing if they go out of business. Consumers will choose other solutions – other circumvention tools, foreign VPNs – and in the process learn more about how circumvention works in China. Educating the market at this stage will be very very valuable.

I think this is also one of the first times that the authorities have said that VPNs serve a purpose. If they continue with this line of messaging, they are actually saying that using a VPN is legal, not illegal. Companies are the main drivers here. If companies have problems accessing the resources that they need to run their businesses, the government will hear about it.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”85698″ img_size=”medium” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/02/six-sites-blocked-by-chinas-great-firewall”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Index: You wrote pessimistically on your blog of Google’s attempts to end censorship, and mentioned that yourselves and other companies could have far more success with access to Google’s resources. How optimistic do you feel about reaching those goals if Google continues to drag its feet?

Smith: If Google continues to sit back and do nothing except take credit for working hard to “end online censorship everywhere” we will still reach our goals. We could get there faster if we worked with Google, but they are not essential to the solution. The only explanation for Google’s inaction in fighting censorship is that they want to “re-enter” the China market by self-censoring Google Play. This would not affect our day-to-day operations too much, but it would really signal the beginning of the end in terms of working in partnership with the Chinese authorities on censorship. Google would join Apple, LinkedIn, Microsoft and many others as a bad actor, leaving only one path forward for new entrants to the China market – self-censorship.

Index: There has been talk of Chinese tech companies poaching talent from the US en masse amid President Trump’s crackdown on foreign labour and uncertainty around his stance towards Silicon Valley. Do you think this would give extra momentum to the anti-censorship movement in China?

Smith: Good question – never thought of that before.

Yes, I think this would greatly help the anti-censorship movement. There is a lot of Chinese talent overseas. It will be hard for them to come back to China and suddenly have to do without the social media and networks that they have established overseas. That shared frustration will lead them to find a better solution than just a VPN.

Index: How has your VPN monitoring service been progressing? Have numbers/uptake improved?

Smith: I think Circumvention Central has shown that VPNs are quite volatile in China. What works today may not work as well tomorrow, which you can see in our data. I think we’ve seen Chinese internet users gravitate to made-in-China solutions, like Shadowsocks.

Index: Should we be worried about China launching international state-run media through CCTV? How would it be comparable to the impact of Russia Today, for example?

Smith: China has deep pockets and is really only getting started in terms of establishing their media footprint overseas. They can afford to lose as much money as is needed to get these operations up and running and then to keep them running. But at the moment, the actual content is so poor, it’s laughable. RT seems to at least have professionals working both in front and behind the cameras. I don’t think CCTV quite has the human resources aspect of this down pat yet, but in time, they will compete for talent. However, by the time they are really ready to challenge other media outlets, I believe that foreign governments will likely place obstacles in CCTV’s path if China has not reciprocated by loosening her own media restrictions.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1487260544112-fa906890-8334-4″ taxonomies=”8199″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Feb 2017 | China

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The New York Times is blocked in China.

Last month, China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology unveiled the country’s a new 14-month campaign to tighten control over the internet. The Chinese government is specifically concerned about virtual private networks, which punch holes through the country’s so-called “Great Firewall”. Without the VPNs, China’s internet users are unable to browse some of the world’s largest web sites. So the campaign made big news around the world.

But Charlie Smith of the 2016 Index on Censorship Digial Activism Award-winning GreatFire, an anonymous collective fighting Chinese internet censorship, told us that the VPN campaign is “actually kind of being mis-reported by the press, in general. It’s not as big a deal as it is being made out to be. We’d make a lot of noise if it was a big deal.”

Here are just six sites that are regularly blocked by China’s Great Firewall:

- YouTube

YouTube was first blocked in March of 2008 during riots in Tibet and has been blocked several times since, including on the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests in 2014. At the time of the Tibetan riots, much of China’s population speculated that the YouTube ban was an attempt by the government to filter access to footage that a Tibetan exile group had released.

- Instagram

It’s typical for China’s internet censors to go into overdrive during politically sensitive events and/or time periods, which is why it doesn’t come as a surprise that Instagram was blocked in 2014 after pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. To some, the block on Instagram during the protests exposed Beijing’s fears that people in the mainland might be inspired by the events taking place in Hong Kong. While some parts of the social media site may be restored, the site is still listed as 92 percent blocked.

- The New York Times

In late December 2016, the Chinese government made waves by ordering Apple to remove their New York Times app from the Chinese digital app store. According to the newspaper, the app had been removed on 23 December under regulations prohibiting all apps from engaging in activities that endanger national security or disrupt social order. The New York Times website as a whole has been blocked since 2012 in China, after the newspaper published an article regarding the wealth of former prime minister Wen Jiabao and his family. People turned to the NYT app after the blockage in order to maintain access to the the paper’s stories. Now that the app is blocked as well, the New York Times is only available to those who had downloaded the app before its removal from the store.

- Bloomberg

In June of 2012, the popular business and financial information website published a story regarding the multimillion dollar wealth of Vice President Xi Jinping and his extended family. Considering this story too invasive, the Chinese government blocked Bloomberg and has yet to reopen the site to the public. At the time, the Chinese government was going through a period of transition, as power shifted from then President Hu Jintao to Jinping.

- Twitter

Censors in China blocked access to Twitter in June of 2009 in anticipation of the 20th anniversary of the pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square. The move seems to reflect the government’s anxiety when it comes to the anniversary and the sensitive memories that come with it. The blocking of Twitter has also allowed for the rise of the Chinese app Weibo, a censored Twitter clone, which quickly became one of China’s most popular.

- Reuters

One of the more recent bans by the Chinese government came in the form of the international news agency Reuters. In March 2015, the organisation announced that both its English and Chinese sites were no longer reachable in the country . China has blocked media outlets like Reuters in the past, but these moves have always come after the release of a controversial story. In the case Reuters, the ban seemed to have come out of nowhere, with the reason behind the blockage still unclear.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1487260644692-d841ab7e-8ed3-4″ taxonomies=”85″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Fionnuala McRedmond – Dublin

Fionnuala McRedmond – Dublin Júlia Bakó – Budapest

Júlia Bakó – Budapest Samuel Earle – Paris

Samuel Earle – Paris  Samuel Rowe – London

Samuel Rowe – London Tarun Krishnakumar – New Delhi

Tarun Krishnakumar – New Delhi Sophia Smith-Galer – London

Sophia Smith-Galer – London Constantin Eckner – St Andrews

Constantin Eckner – St Andrews Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm

Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm