18 Jan 2017 | Magazine, News and features, Turkey, Volume 45.04 Winter 2016 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Imprisoned journalists make headlines, but the Turkish government has a more insidious method for controlling the media, researchers BURAK BILGEHAN ÖZPEK and BAŞAK YAVCAN argue in an unpublished report excerpted in the winter edition of Index on Censorship magazine” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”84920″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

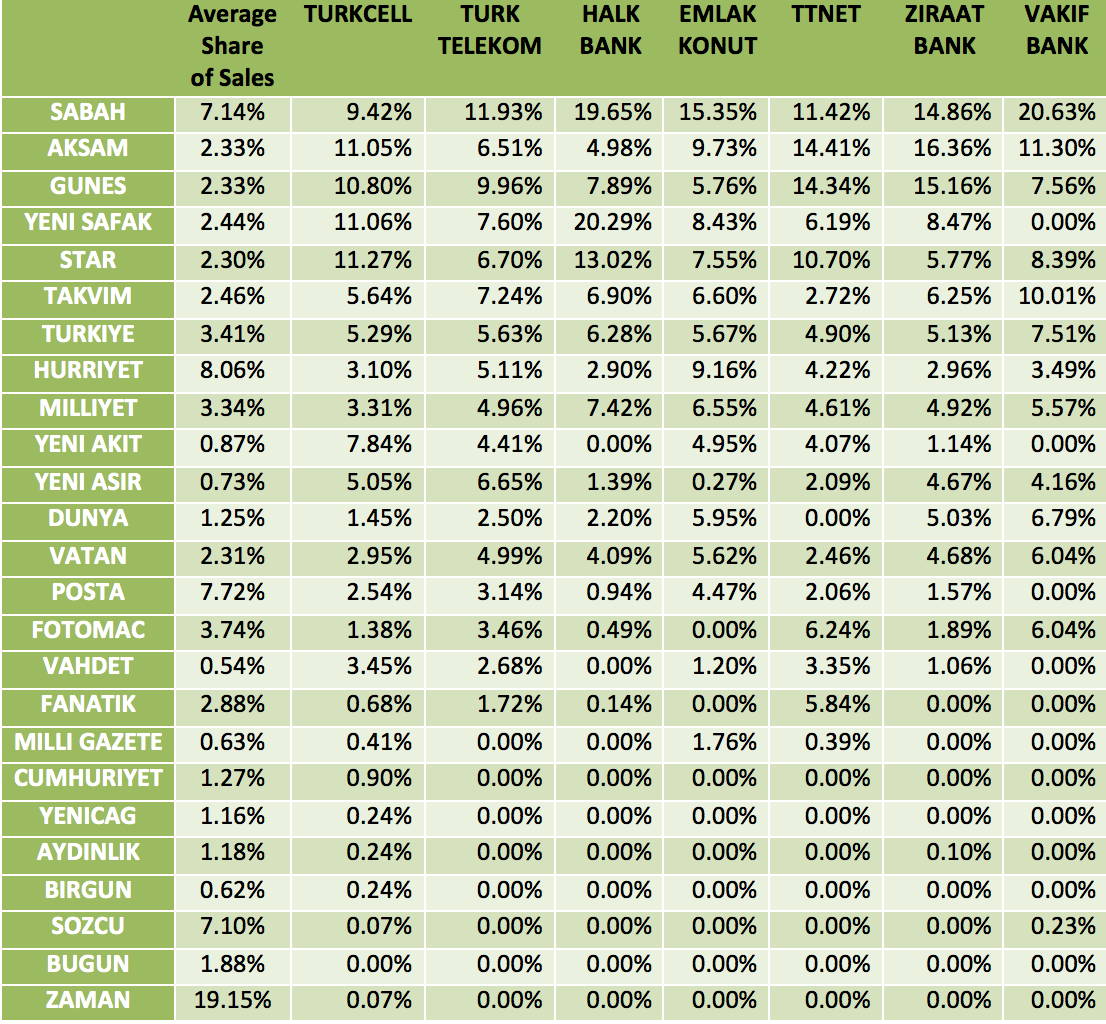

Advertising is the latest way for the Turkish government to lean on the media to stop critical stories going into the press, according to unpublished research.

The large advertising budgets of state-controlled Turkish industries like banks, telecoms companies and Turkish Airlines are being used by the government to develop a financial grip over newspapers and control what they report.

Patterns of advertising during 2015 suggest that newspapers which do not toe the government line, or are hostile, are being starved of those revenues.

For instance, Sabah, a newspaper particularly sympathetic to the government, received more than 20% of the advertising budget of the state-controlled bank Halk Bank, while the independent Hürriyet received only 2.9%, despite both having a similar circulation.

Government-controlled telecoms company Turkcell also favoured Sabah by giving it 9.4% of its advertising, while Hürriyet took just 3.1%.

The situation was similar for another state-controlled telecoms company, Turk Telekom: Sabah received more than twice Hürriyet’s share of their total advertising.

Their research found that any paper critical of the government – those associated with the social democratic movement, liberalism, Kemalism, nationalism, Islamism – was either discriminated against, or excluded entirely, when it came to crucial advertising revenue.

Table: Daily newspapers’ share of advertising from part-public firms in 2015

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Burak Bilgehan Özpek is an associate professor and Başak Yavcan is an assistant professor in the department of political science and international relations at TOBB University of Economics and Technology in Ankara. This is an extract of their article from the winter 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, which is based on their as-yet unpublished research into press freedom in Turkey. The magazine article can be read in full for free on Sage Journals until 31 January 2017.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fashion Rules” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F12%2Ffashion-rules%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear.

In the issue: interviews with Lily Cole, Paulo Scott and Daphne Selfe, articles by novelists Linda Grant and Maggie Alderson plus Eliza Vitri Handayani on why punks are persecuted in Indonesia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/12/fashion-rules/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Jan 2017 | France, Greece, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”81193″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

A Hatay court issued a detention order for Ceren Taşkin, a reporter for the local newspaper Hatay Ses, on the basis of her social media posts, news website Gazete Karinca reported.

Taşkin was detained earlier for “spreading propaganda for a terrorist group” via her social media posts. Taşkin was arrested and sent to prison on 12 January on the same charges.

Her arrest brings the number of journalists in prison to 148, Platform 24 reported.

The National Radio and TV Council has banned independent Russian television channel Dozhd from broadcasting in the country.

“The channel portrayed the administrative border between Crimea and Kherson region as the border between Ukraine and Russia,” national council member Serhiy Kostynskyy said during a council meeting, Interfax-Ukraine reported.

According to Kostynskyy, the channel repeatedly violated Ukrainian law in 2016 by broadcasting Russian advertising and having Dozhd journalists illegally enter annexed Crimea from the Russian Federation without receiving special permission.

The ban is set to be officially published by the authorities on 16 January, Interfax-Ukraine reported.

Dozhd Director Natalya Sindeyeva said that the channel is broadcasting through IP-connection without direct commercial advertising in Ukraine and follows the Russian Federation law requiring that media outlets use maps to show Crimea as part of Russia.

Dunja Mijatovic, media freedom representative at the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, wrote on her Twitter that this decision is “very damaging to media pluralism in Ukraine.”

Police arrested Giannis Kourtakis, publisher of Parapolitika newspaper, and its director, Panayiotis Tzenos, following a lawsuit filed against them for libel and extortion by the defence minister and leader of the Independent Greeks Party (ANEL), Panos Kammenos, the news website SKAI reports.

Kourtakis said he voluntarily went to police headquarters after being informed about the lawsuit, while director Panagiotis Tzenos was arrested in his Athens office.

ANEL issued a statement stressing that the lawsuit was prompted by allegedly slanderous claims about Kammenos’s son, saying that he was an “anarchist” and involved in a terrorist group on their radio programme which aired on 9 January.

In July 2015, Kammenos gave Athens press union (ESIEA) a list of journalists who had allegedly received improper funding through advertising from the state health entity KEELPNO, which included the Parapolitika executives.

According to SKAI, Kammenos claims that the journalists made slanderous statements about his son in order to make him retract allegations that the Parapolitika executives were receiving funding.

The public prosecutor who investigated the lawsuit has since reportedly dropped charges of criminal extortion.

Greece’s main journalists’ union and opposition parties have expressed concern over the general tendency of police’s interventions to journalists’ offices.

“Journalism must be exercised according to specific rules, but also press freedom must be defended and protected,” the Journalists’ Union of the Athens Daily Newspapers writes in its statement.

Vladislav Ryazantcev, correspondent for the independent news agency Caucasian Knot, reported on Facebook that he was assaulted by five unknown individuals whose faces were covered by scarves.

According to Ryazantcev, one of them grabbed his hand and asked him to “follow him for a talk.” Right after that an additional four individuals came up and started to hit the journalist on the head.

Ryazantcev reported that bystanders then helped rescued him.

“I do not know what the attack is connected to,” he wrote on Facebook. He later filed a complaint to the police.

The day before on 9 January, Magomed Daudov, speaker of the Chechen parliament, published threats against editor-in-chief of the Caucasian Knot, Grigori Shvedov, on Instagram.

A TV crew working for TF1 channel was reportedly assaulted in Compiègne while trying to film a building set to be emptied of its inhabitants because of alleged high criminality linked to drug trafficking, Courrier Picard reported.

“We tried to film a story there this morning. Our crew was attacked and stoned by thugs who stole our camera in this unlawful zone. It was very violent,” TF1 presenter Jean-Pierre Pernaud said. The assault occurred in the Close des Roses neighbourhood.

One of the journalists told Courrier Picard that the channel would file a complaint.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Jan 2017 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mehman Huseynov (Twitter)

The undersigned organisations strongly condemn the abduction and torture of Azerbaijani journalist Mehman Huseynov and call on Azerbaijan’s authorities to immediately investigate the case and to hold those responsible accountable. Moreover, Huseynov’s conviction should be overturned and the travel ban against him lifted. We further call upon the Azerbaijani authorities to immediately and unconditionally release all journalists, bloggers and activists currently imprisoned in Azerbaijan solely for exercising the right to freedom of expression.

Mehman Huseynov, Azerbaijan’s top political blogger and chairman of the local press freedom group, Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), the country’s leading press freedom group, was abducted in Central Baku at around 8 pm local time on Monday 9 January. He was pushed into a vehicle by unknown assailants and driven away. His whereabouts were unknown until early afternoon on Tuesday, when it emerged that Huseynov had been apprehended by unidentified police agents.

On 10 January, Huseynov was taken to Nasimi District Court, where he was tried on charges of disobeying the police (Article 535.1 of the Administrative Offences Code), which carries a sentence of up to 30 days in jail. The Court released him; however, he was fined 200 AZN (approx. 100 EUR).

Huseynov said he was tortured while in police custody. He reported being driven around for several hours, blindfolded and suffocated with a bag. He also said that he was given electric shocks in the car. On being brought to Nasimi District Police Department he lost consciousness and collapsed. An ambulance was called, and he was given painkillers and sleep-inducers by way of injection. His lawyers confirmed that his injuries were visible during the court hearing. The court also ordered that Nasimi district prosecutor’s office conduct investigation into Mehman Huseynov’s torture reports.

“We resolutely denounce this act of torture and wish Mehman Huseynov a rapid recovery,” said Gulnara Akhundova, the Head of Department at International Media Support. “All charges against Huseynov must be dropped unconditionally, and those responsible for his torture should be tried in an independent and impartial manner, as should those in the chain of command who are implicated”.

‘The fact the Mehman Huseynov was convicted of disobeying the police for refusing to get into the car of his abductors beggars belief. We know that the Azerbaijan authorities have a long history of bringing trumped up charges against writers and activists. His conviction should be overturned immediately’ said Salil Tripathi, Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

“This is another example of continued repression against journalists in Azerbaijan, which is why RSF considers Aliyev a predator of press freedom. Huseynov is one of dozens of journalists and citizen journalists who remain under politically motivated travel bans. Although he has been released, he remains at serious risk. The international community must act now to protect him and other critical voices in Azerbaijan.” said Johann Bihr, the head of RSF Eastern Europe and Central Asia desk.

Although Huseynov’s family and colleagues had repeatedly contacted the police since his disappearance on 9 January 2017, they were not informed about his arrest until early afternoon the following day when he was brought to court. Hence, the undersigned organisations consider Huseynov’s abduction as an enforced disappearance, defined under international law as the arrest or detention of a person by state officials, or their agents, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty, or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts. The UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances has repeatedly clarified that ‘there is no time limit, not matter how short, for an enforced disappearance to occur’. As a signatory of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED), Azerbaijan is obliged to refrain from acts that would defeat or undermine the ICPPED’s objective and purpose.

Despite the much-lauded release of political prisoners in March 2016, the persecution of critical voices in Azerbaijan has accelerated in recent months. Currently, there are dozens of journalists and activists behind bars for exercising their right to free expression in Azerbaijan.

“The government has sought to destroy civil society and the media in Azerbaijan, while developing relations with Western states to secure lucrative oil and gas deals”, said Katie Morris, Head of the Europe and Central Asia Programme at ARTICLE 19.

“While the government may release a journalist one day, the following day they will arrest or harass others, creating a climate of fear to prevent people speaking out. The international community must clearly condemn this behaviour and apply pressure for systemic reform”, she added.

“We must stop the sense of impunity on attacks against journalists and human rights defenders in Azerbaijan, of which this attack against Mehman Huseynov is a sad illustration. The international community must seriously address this climate of impunity and take concrete actions, through the Council of Europe and the United Nations Human Rights Council, to regularly monitor the human rights situation in Azerbaijan and hold the authorities to their commitments in this regard,” said Ane Tusvik Bonde, Regional Manager for Eastern Europe and Caucasus at the Human Rights House Foundation.

The undersigned organisations call on the authorities to take the necessary measures to put an end to vicious cycle of impunity for wide-spread human rights violations in the country.

We call on the international community to undertake an immediate review of their relations with Azerbaijan to ensure that human rights are at more consistently placed at the heart of all on-going negotiations with the government. Immediate and concrete action must be taken to hold Azerbaijan accountable for its international obligations and encourage meaningful human rights reform in law and practice.

Supporting organisations:

ARTICLE 19

Civil Rights Defenders

English PEN

FIDH – International Federation for Human Rights

Front Line Defenders

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights

Human Rights House Foundation

IFEX

Index on Censorship

International Media Support

International Partnership for Human Rights

NESEHNUTI

Netherlands Helsinki Committee

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN America

PEN International

People in Need

Reporters Without Borders

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1484232949524-420ae29e-2c22-0″ taxonomies=”7145″][/vc_column][/vc_row]