This article first appeared in Volume 54, Issue 3 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Truth, trust and tricksters: Free expression in the age of AI, published on 30 September 2025. Read more about the issue here.

We are right to be concerned about what artificial intelligence is doing to our present and what it might do to our future. But I am more worried about what it can do to our past.

Access to archives is becoming harder. Manuscripts are fragile, and verifying historical evidence contradicting established narratives is time-consuming. Technology makes history seem fun and exciting by enabling direct communication with historical figures and using visuals that simplify the past, but it weakens our understanding. Artificial intelligence reshapes research by digitising archives and analysing data quickly, but it poses risks. AI often lacks academic rigour, drawing from biased sources and oversimplifying complex events. It presents information with unearned authority, spreading errors rapidly. Unlike historians, AI cannot evaluate credibility, weigh accounts or identify gaps in records.

The result is that our history runs the risk of being skewed towards what’s most accessible online: mainstream narratives drawn from popular databases, digitised books, encyclopaedias, widely-read history books and even crowd-sourced portals. Marginalised voices – Indigenous people, minorities, or communities without digitised records – risk being erased further. When AI amplifies the dominant version of events, alternative interpretations fade into obscurity.

For all its potential, AI cannot replace the human historian. Critical judgment, contextual thought and insights, and the ability to navigate conflicting evidence and picking plausible theories remain essential to safeguarding the integrity of the past.

Consider a recent experiment by Indian historian Anirudh Kanisetti. A trained engineer, Kanisetti has written two engrossing books on the Chaulukyas and the Cholas, two medieval-era dynasties of southern India. Despite his background in engineering, or perhaps because of it, he is sceptical of the use of AI in history. He decided to challenge the Goliath. He sought AI assistance and then wrote about his experience on Instagram. He calls AI “language calculators, and not very good ones”. He asked Copilot, Microsoft’s AI tool which uses OpenAI’s ChatGPT, to write an essay based on his work about a medieval regiment in India.

In its references, the tool produced a paper by an academic Kanisetti knew of, but he had never heard of this paper. He called out Copilot, and it immediately admitted it had made up the fact. Its subsequent apology was insincere. Kanisetti then posed another query, instructing Copilot to cite primary sources. This time, the bot confidently misquoted primary sources and, again, admitted the fabrication when he called it out.

Kanisetti is worried because he knows the sources and can find out when AI is lying; other users may not be that knowledgeable and may rely on AI to do the grunt work of checking citations. As he puts it: “Large language models (LLMs) are trained to seem to be helpful, so you think they have value. But they are actually faffing, lying, fabricating … Engagement generates shareholder value.”

Our information ecosystem is being destroyed, he added.

He has grasped the essence of the problem that is bothering many historians in the global south.

The future historian’s skillset

Aanchal Malhotra, who has written a fascinating history about India’s Partition, told me: “This thought of AI rewriting history is new but a terrifying one, because of the scale it can achieve.”

Doyenne of Indian history Romila Thapar told Index: “What AI can do to history is in a sense already being done by what the Hindutva-vadis [right-wing Hindu nationalists] are doing to Indian history. It is an alternative, distorted history that they are propagating. So far, professional historians are dismissing it by showing that there is no reliable evidence to provide proof of what is being stated in the Hindutva version. One can predict that with the availability of AI there can be massive forging of many documents that will be put forward as proof. So training in professional history will require the ability to recognise forged documents, especially if they are documents that are said to belong to earlier times. The historian of today has to be a multidisciplinary person, but the historian of tomorrow will also have to be trained in the technology of verifying documents and publications.”

She wonders if the techniques of historical excavation will need to change, since the authenticity of three-dimensional artefacts gathered from sites will have to be proved. As soon as an artefact is discovered, will it need to be intensively photographed and marked and documented and a tiny sample be analysed? This will make excavation absurdly expensive if the veracity of every object has to be proved, she adds. And she is concerned about how AI’s apparent ability to bring characters from the past back to life would interfere with what we know to be true.

She also worries about what AI can do to historical questioning and education. If students start asking AI to write their papers and tutorials (as many are), they will become masters at writing prompts, but not at drawing their own analysis. They will know how to use a machine, but truth will elude them. “They won’t know why they have written what they have,” she said.

History abounds with examples of misinterpretations, such as the figurine of a horse in Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan, which suggested that the horse had been domesticated as early as the second millennium BC.

Peter Frankopan, who teaches history at Oxford, told Index: “The skill of a historian is to be able to deal with complex materials… The idea of lots of forgeries is as old as writing systems. Information has always been used and manipulated to embed hierarchies, to spread falsehoods and to manipulate people – whether literate or otherwise. So training historians in the present and future simply requires the right skills to be learned, and the discipline of asking the right questions. Clearly, we have some challenges ahead; but there have always been such problems in the past.”

The risks heighten with the seductive charm of AI-generated visual imagery. Manu Pillai, who has written thoughtful and engrossing books on the history of southern India and, more recently, about the making of modern Hindu identity, told Index it was only a question of time before we find sophisticated imagery or videos generated by AI that would make the crudely written WhatsApp messages appear believable. There are twin dangers in India, he said. There is high digital access but weak digital literacy, “which means large segments of people are likely to be misled. We also live in a time when more and more people have an appetite for conspiracy theories and for ‘alt’ facts, and many therefore would be predisposed to swallow some of the material that comes their way”.

AI for good…occasionally

AI does provide notable benefits, such as drawing patterns from vast amounts of data and deciphering handwriting. It helps restore and better understand complex historical texts. The Arolsen Archives use AI to catalogue documents related to Nazi persecution victims. Yad Vashem uses AI to identify unknown Holocaust victims. The USC Shoah Foundation and Illinois Holocaust Museum use AI-driven holographic displays, voice recognition and virtual reality to create transparent, immersive experiences for remembrance and education.

AI’s inability to separate truth from lies is the real danger. As an aggregator, if it finds a particular version of a story cited more often, it is trained to assume it is part of the mainstream discourse. It overemphasises the dominant narrative over alternative views, which reinforces misinterpretations and falsehoods.

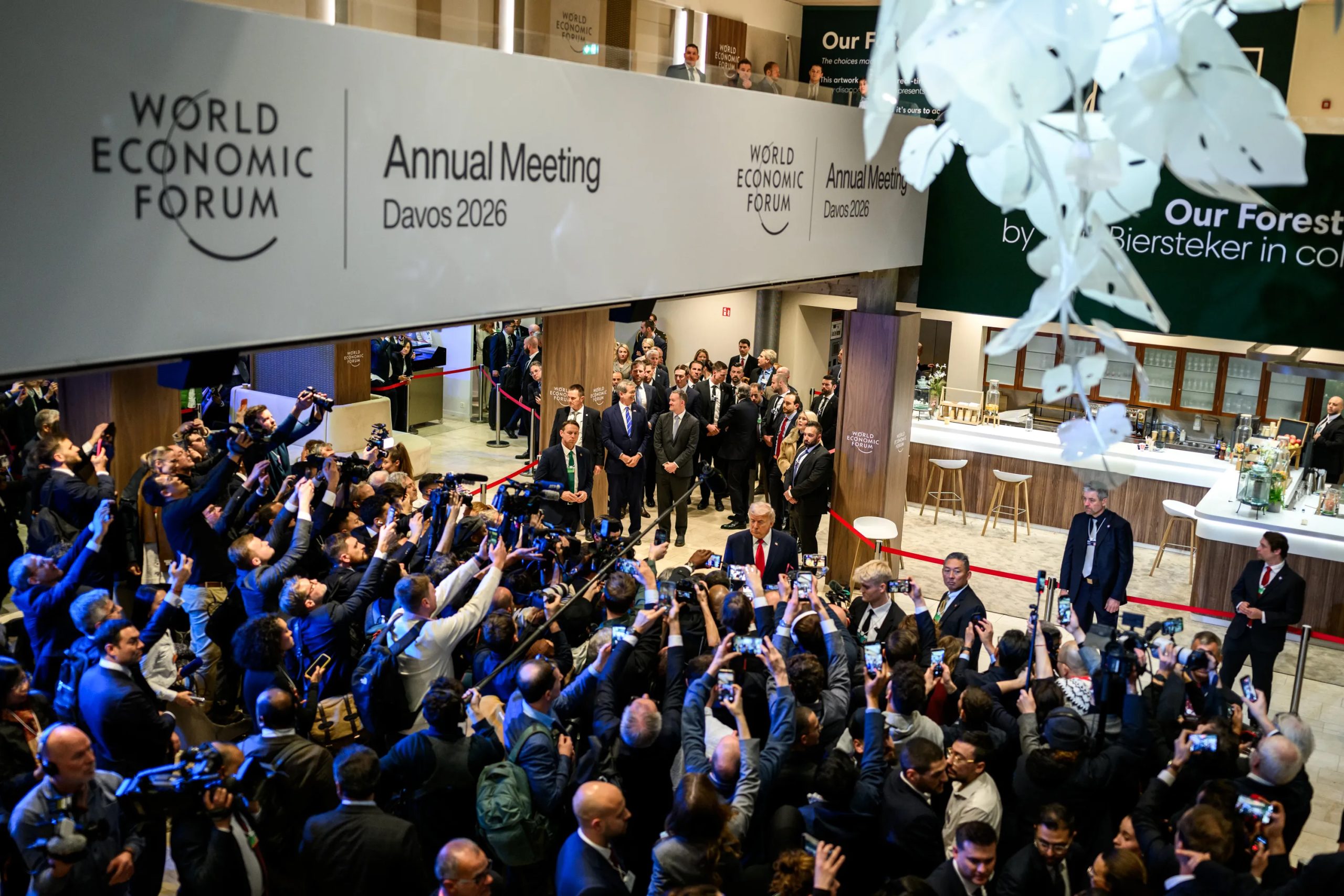

Manila-based Singaporean historian Thum Ping Tjin (better known as PJ Thum) is wary. The founder of New Naratif notes that throughout human history, tools have emerged to make our communication and information exchange quicker, and these tools have raised alarms. They have inevitably been co-opted by those with money and power in order to get more money and power. “They have used those tools to present versions of history to further their own goals,” Thum said.

“In many cases, the worst-case scenario you fear already exists,” he told Index. “Southeast Asian governments have long used their resources to fabricate, censor and present their own version of history and their power to enforce it. Singapore has had an entire industrial complex of official historians repeating the ‘official’ version of history. Professional historians who seek to correct the record are treated as public enemies.”

Thum himself underwent hours of gruelling questioning by government officials when he critiqued Singapore’s official interpretation of how it got separated from Malaysia, and the government introduced a new law intended to attack disinformation but which in effect ensured that the dominant, state-approved narrative would prevail.

Alarmed by the attacks on crucial aspects of American history, primarily dealing with race, the American Historical Association Council has issued guidelines based on principles that reinforce the need for historical thinking, reminding us that AI produces texts, images, audio and video, but not truth. It also warned about AI’s tendency to hallucinate and introduce false certainties.

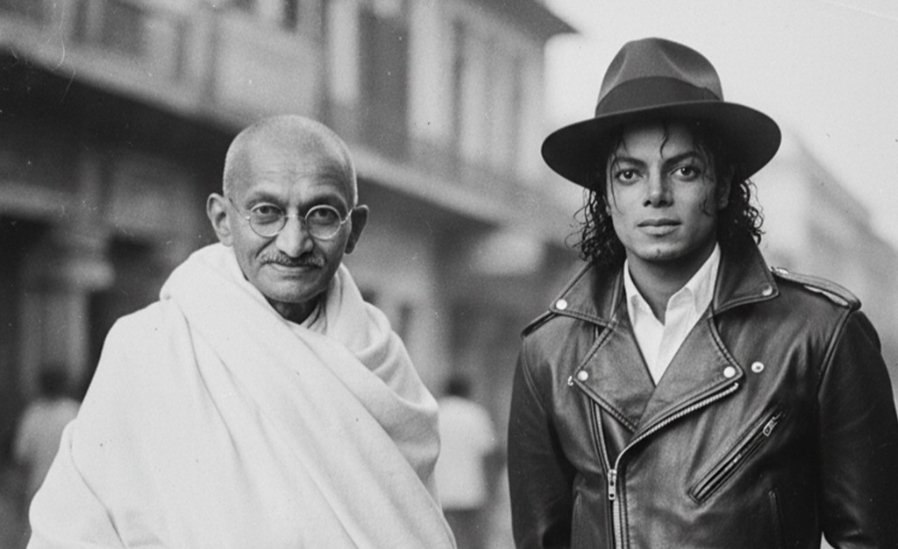

AI’s biggest impact on history is deepfake technology. Erasing inconvenient truths or spreading lies isn’t new – Joseph Stalin famously airbrushed Leon Trotsky out of photos. In the late 1990s, a Malaysian newspaper altered photos to remove Anwar Ibrahim after he fell out with prime minister Mahathir Mohammed.

The problem of AI fakes

Forged documents have long confused historians; for example, Nazi era expert Hugh Trevor-Roper believed the fake Hitler diaries were genuine because of their voluminous content. The fabricated 1903 Protocols of the Elders of Zion fuelled antisemitism and conspiracy theories. Recently, AI-generated deepfake videos, such as one of US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, which depicted her in Congress arguing that a jeans ad featuring Sydney Sweeney was racist, have gone viral, highlighting new dangers in disinformation.

Kanisetti points out that many Indians consume historical materials now through videos. These don’t claim authenticity, but to the untrained mind the realistic-looking videos appear to be well-researched. “The right wing has no incentive to doctor primary sources yet, because the general public is already uninterested in the ambiguities of evidence-based history,” he said. Many viewers want affirmation of their beliefs; they no longer care if what they are seeing is accurate.

In What is History?, EH Carr wrote: “The facts speak only when the historian calls on them: it is he who decides to which facts to give the floor, and in what order or context.” The selection of facts is integral to historical research. Good historians must be aware of their personal biases and the context of their work. Only humans have the capability to understand the emotions involved and the ethical choices that need to be made; it is why at universities, history is part of the humanities department and not in a scientific lab.

Historians are quick to caution. One of the biggest risks is Holocaust denial and revisionism. Unesco published a report last year with the World Jewish Congress, which showed how hate groups could use AI to deny the Holocaust, including by fabricated testimonies and altered historical records. The Historical Figures app allows users to ‘chat’ with prominent Nazis such as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, and it falsely claims that Goebbels (for example) was not intentionally involved in the Holocaust and had tried to prevent violence against Jews. Unesco has its own recommendations for ethics in AI, which it urges governments to follow. It has also asked tech companies to improve their standards and act responsibly.

But governments have neither the capacity nor, in some cases, the willingness to prevent disinformation from spreading widely. Can states be trusted? Can corporations, which are incentivised by maximising shareholder value? Open-source algorithms, digital watermarking and community-based content moderation are all necessary potential solutions, but none is sufficient. Educating the public, particularly young people, on how to critically evaluate information and recognise misinformation is crucial to combat the negative impacts.

Thum told me: “The only defence against this is by educating ourselves to be more sceptical and information-literate; by democratising the tools and skills of history; and by teaching people to be more sceptical and critical of those with information and power, so that we are less likely to be tricked by AI or whatever the next technology is.”

In 1987, I interviewed Salman Rushdie in Bombay, as the city was then known, when he had completed writing The Satanic Verses. Other than his editors, few knew what the novel was about.

When I asked him, he said: “It is about angels and devils and how it is very difficult to establish ideas of morality in a world which has become so uncertain that it is difficult to even agree on what is happening. When one can’t agree on a description of reality, it is very hard to agree on whether that reality is good or evil, right or wrong. When one can’t say what is actually the case, it is difficult to proceed from that to an ethical position. Angels and devils are becoming confused ideas … It is an attempt to come to grips with that sense of a crumbling moral fabric or, at least, a need for the reconstruction of old simplicities.”

AI makes us believe in simplicities, that truth is easy to access, and that answers to complex questions are just one click away. It is the product in our age of instant gratification. Reality, like history, is more nuanced. The challenge lies in our not being condemned to repeat it.