7 Nov 2025 | Middle East and North Africa, News, Yemen

On the outskirts of Sanaa, 28-year-old Badr Yaseen sits inside a four-square-metre salon. The interior wall is lined with full-length mirrors, and scissors, electric shavers, combs, and hair care products are neatly arranged on a cupboard and small shelves.

Yaseen greets each customer with confidence and warmth. Once they settle into the chair, he politely asks about their preferred haircut style before getting to work. As he cuts, he keeps up a friendly conversation, making the experience relaxed and personal.

Yaseen did not inherit his profession from his father or grandfather. He is the first in his family’s generation to take up this work. It has been a decision many in his family have called an act of “mutiny” against long-held traditions.

His brothers urged him to give up the job, and his uncles tried to dissuade him from continuing. Relatives frowned upon his choice, believing that Yaseen’s work as a barber “shames” the family. They all believe that this profession is only suitable for the “lower class”. Such beliefs run deep, woven into the fabric of social hierarchy and pride.

Yet Yaseen defied these norms. He has disregarded the opinions of his family, friends, and acquaintances. He has refused to bow to social censorship or the entrenched prejudices surrounding his choice.

In a country where a decade-long conflict has devastated the economy and wiped out countless jobs, Yaseen has prioritised survival over social status. Like him, many others have defied social norms and stereotypes, doing whatever they can to endure these harsh times.

“Not ‘wrong,’ not ‘obscene,’ not ‘immoral’.” These are the verbal bullets Yaseen fires back at anyone who criticises or disrespects him.

In Yemen, the law prohibits discrimination based on colour, origin or job. Despite that, discriminatory norms remain a prevalent plague in society.

Survival over status

Yaseen is classified as a tribesman. Married with four children, he was miserable when he was jobless two years ago, he recalls. Financial troubles darkened his life. He was willing to accept any job, except being a fighter for the war rivals in his country.

“I approached a salon owner and asked for work. He offered me a job, and I began as a barber,” Yaseen told Index.

When he started, he already had the know-how. “My brothers and close friends used to need a haircut, and I would do that. I did not do it for money. That is how I developed my skill.”

Yaseen was not planning to be a barber. It was just a favour or entertainment. Now, it is his money-making job.

“Had I been kept imprisoned by the social norms, my suffering would linger, and my children would starve. A barber is not a lower person. That is how hardships changed my mindset.”

Since 2015, a destructive civil war coupled with airstrikes has devastated Yemen, and it remains unresolved. Famine and food insecurity have prevailed, risking the lives of millions of people.

United Nations reports reveal that over 17 million people are going hungry in Yemen. This figure may rise to 18 million by February next year. Women and children are the most vulnerable.

With this bleak reality, Yaseen and countless of his like no longer disdain “lower class” jobs.

Yaseen has a friend named Nasser. Two months ago, Nasser shared his business idea with Yaseen: opening a chicken slaughterhouse. Although being a butcher is often considered a lower-class job among Yemenis, Nasser – himself a tribesman – doesn’t care about such judgments.

“Call him a butcher. That won’t cost him his life. Hunger and unemployment will,” Yaseen said with a serious tone.

The teacher-turned painter

Public employees in Yemen have not been immune from the economic consequences of the decade-long war. Those who were once proud of their job titles abandoned their careers and began entering fields they had never worked in before.

Before the war erupted in 2015, Yahia, 42, had been a passionate teacher in a government school in Sanaa. His passion died down and morale vanished as the war was prolonged. Salaries stopped coming as war rivals held one another responsible for paying public workers.

“I kept coming to the classroom for three years unpaid. I exhausted my savings and felt unprecedented financial pressure. I was compelled to take a U-turn in my professional life,” he told Index.

Over one million public employees have not been paid their regular salaries since September 2016. About 6.9 million people are estimated to live on that income.

In 2020, Yahia began working as a helper for a professional painter in Sanaa. Within six months, he learned enough about the job. Now, he considers himself as an “outstanding painter”.

Yahia feels no embarrassment when he puts on his paint-stained clothes and heads to work.

“I left the classroom and set aside the markers, picking up brushes and rollers instead. Surviving amid war is an accomplishment,” he said, his voice filled with gratitude.

The veiled seller in the qat market

The 2024 Humanitarian Response Plan for Yemen estimated that 18.2 million people required humanitarian assistance, including 4.2 million women and 4.8 million girls. But not every woman waits for assistance or surrenders to hunger.

Um Ahmed, 30, sits on the ground in a popular market in Sanaa selling bags of qat, a narcotic leaf ubiquitously consumed in Yemen. She begins at 11am and leaves at 2pm.

She places the qat bundles before and beside her. Customers stand or sit to pick and look at the product. Bargaining over the price begins. Eloquent and confident, she is a glib bargainer. Her face is veiled. Only her narrow eyes are visible.

Qat selling is dominated by men in Yemen. However, Um Ahmed and others of her like have tried it and fared well. Today, she does not fear what society thinks of her.

“When I started this work four years ago, few encouraged me and many found it weird. But the weird thing is to stay idle, starving to death,” Um Ahmed told Index.

She earns 5,000 Yemeni riyal ($20) a day. Her profit can increase or decrease.

“Today, I spend on myself and my three children and save some of my income. If I continued being ashamed of work and became obedient to unfair social norms, I would be a hungry loser,” she says.

7 Nov 2025 | Asia and Pacific, Burma, China, News, Volume 54.03 Autumn 2025

If you had told Sai a month ago that his latest exhibition would force him to flee across the world, he might not have been surprised.

After spending hundreds of days hiding above an interrogation centre in his home country of Myanmar, sneaking cameras illegally through military checkpoints and risking his life raising awareness about the horrors of the junta through art, he seems immune to shock.

He told Index that to get out of the country and come to Thailand in 2021, he had to “imagine himself dead”.

This experience influenced his work as an artist and curator who has become renowned for his powerful works about the trauma of political persecution and Myanmar’s military coup.

His latest Bangkok show, co-curated with his wife, is Constellation of Complicity: Visualising the Global Machine of Authoritarian Solidarity. It links his experiences with artists from around the world in a powerful exploration of how authoritarian regimes collude internationally in systems of repression. But for some, its message struck too close to home.

It opened at the end of July at the Bangkok Arts and Cultural Centre (BACC), where Sai and his wife had settled in exile. But shortly after it opened, he says that Chinese embassy officials arrived with Thai authorities and demanded that it be shut down.

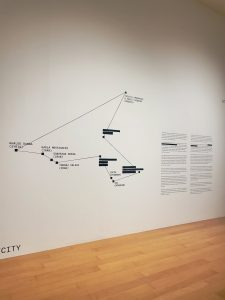

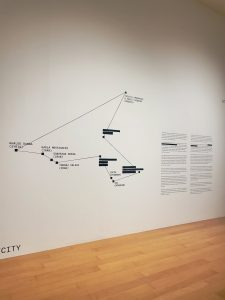

A display showing artist names which were redacted after complaints from Chinese embassy officials in Thailand. Photo: Pran Limchuenjai

A compromise was reached, but what followed was a wave of censorship that stripped the audacious exhibition of artists’ names, politically sensitive references and some of its bravest works.

The names of Uyghur artist Mukaddas Mijit, Tibetan artist Tenzin Mingyur Paldron and Hong Kong artist duo Clara Cheung and Gum Cheng Yee Man were all blacked out and their works pared down or removed entirely.

Tenzin Mingyur Paldron was the most heavily censored, with the televisions screening his video installations about the Dalai Lama and LGBTQ+ Tibetans switched off.

Tibetan and Uyghur flags were removed and a description of the censored artists’ homelands was concealed with black paint. An illustrated postcard comparing China’s treatment of Muslim populations to Israel’s was also taken down.

Sai, who goes by a single name to protect his identity after repeated warnings that he is being sought by the junta, is no stranger to state power.

His father, the former chief minister of Myanmar’s biggest state, was abducted and jailed on falsified charges after the 2021 coup. His mother lives under 24-hour surveillance, constantly fearing for her safety.

This experience has shaped both his politics and his practice. “My works usually combine social experiment with institutional critique,” he explained. “But since 2021, it has mostly been reflective of my lived experience.”

This inspired the most recent exhibition, which brings together exiled Russian, Iranian, Syrian, Burmese, Tibetan, Uyghur and Hong Kong artists. It’s a snapshot of life under repression, mapping the contours of a global authoritarian network.

“We formulated what would happen if all of the oppressed united together against the few [oppressors],” Sai explained about his defiant stance which quickly stoked retaliation.

“We were very used to absurdity, with what happened to my father, my country, my loved ones. But this was another international-level absurdity happening – the absurdity of transnational repression.”

Thailand, which Sai had once seen as a place of refuge where a large community of pro-democracy artists and dissidents from Myanmar could work with relative freedom suddenly felt perilously unsafe.

“Thailand has long tried to balance being a host for dissidents with keeping strong relations with China,” he said. “The intervention by the CCP, and Thailand’s willingness to comply with it, shows just how fragile that space really was.”

After being informed that police were looking for them, Sai and his wife booked flights out of the country. They fled within hours and are now seeking asylum in the UK.

But he is sympathetic towards the BACC. It is funded by the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, and he said it decided to censor the show due to its “connection to city authorities and the political sensitivities such as threats to diplomatic relations between Thailand and China”.

“They were under immense pressure and chose partial censorship as a way of protecting the institution,” he concluded.

However, the irony was almost too much to bear as the Chinese response handed the exhibition, which might otherwise not have been noticed, a global platform. The artists who had their names blocked out have gone viral, reaching new heights of fame. Visitors have flocked to the exhibition, while the gallery has faced uproar for its decision to bow to censorship.

Sai also says it also taught him a valuable lesson. “When we got out [of Myanmar] we promised that we would make something for our country. Now we’ve learned something – we can’t just do it for our own country, because all of these geographical boundaries are just constructs. We live in one world, and we need to fight against global repression together.”

7 Nov 2025 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, News, Statements

During a one-day mission to Budapest on 22 October 2025, partner organisations of the Council of Europe’s Platform for the safety of journalists met with journalists, media representatives, legal experts and representatives of civil society to discuss key issues affecting media freedom, rule of law and free expression. Stakeholders described a severely restricted media environment within which independent journalism operates, while also highlighting the deep political polarisation shaping the run-up to the expected April 2026 elections.

In the past year, the ruling party Fidesz has maintained the most sophisticated system of media capture and control yet seen within the European Union, constructed through sustained dominance over public media, continued consolidation of private outlets under allied ownership, and persistent distortion of the market through control over state advertising, with severe consequences for media pluralism and independent journalism.

While online harassment against independent media has long been documented in Hungary, including campaigns aimed at representatives of the Platform partners, the polarised and divisive nature of the election campaign has increased the severity and nature of the threats. Multiple stakeholders reported targeted harassment and smear campaigns directed at independent journalists and outlets by representatives and supporters of the two most prominent parties and media outlets deemed friendly to the ruling party, many of which are owned by the Government-linked KESMA foundation. The partners were alarmed by reports that journalists have been smeared online and in the media as being affiliated with opposing political parties in an attempt to discredit them as trusted and independent sources of public interest information.

The partners also sought to assess the impact that the draft bill on the Transparency in Public Life had on the work of journalists, media outlets and civil society. If passed, it would have allowed for the blacklisting, financial restriction and potential closure of media outlets receiving foreign funds, having a deeply chilling effect on media. For those able to remain open, they may be forced into exile to be able to continue reporting. The mission heard that the bill remains shelved, with no current indication Fidesz plans to reintroduce it ahead of the 2026 election.

However, the ruling party’s two-thirds parliamentary majority and recent extension of the state of emergency mean the bill could be passed immediately, without public consultation. Many representatives spoke of the uncertainty this proposed bill caused, as well as the resources expended by many to establish contingency plans to ensure they can continue their vital work. With its reintroduction still a possibility, the bill continues to pose an existential threat to what remains of Hungary’s free press.

The Platform further notes that although the foreign funding bill was withdrawn, the Sovereignty Protection Office (SPO), the Government office that would be charged with overseeing the proposed law, has spearheaded the attempted delegitimization of media which receive any form of foreign funding or grant, portraying them as foreign agents and traitors. The SPO’s reports have fed wider online harassment and hate against journalists working for these titles online and on social media, including referring to independent journalists as “political pressure groups”. The SPO has also supported campaigns led by the ruling Fidesz party to target journalists and civil society such as the smearing of leading independent outlets and NGOs.

The Platform’s partners are also concerned about the rise of legal harassment directed at journalists and media outlets, including abusive claims based on GDPR regulations or press correction procedures. While we support processes to hold journalists to account and ensure inaccuracies are addressed, we are concerned by reports that this process has been used to target factual if critical reporting. With the capture of Hungary’s courts by the ruling party a persistent issue, such legal harassment can have a disproportionate impact on public interest reporting.

No progress has been made by Hungarian authorities in aligning domestic law with the EU’s European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) since its full entry to effect in August 2025. Those we met confirmed the absence of any engagement with media outlets or civil society towards this goal. Instead, the Hungarian government has presented the regulation as an authoritarian dictat from Brussels and has challenged the EMFA before the European Court of Justice, seeking to have it nullified.

Following revelations about the abuse of zero-click spyware Pegasus against multiple journalists by Hungarian intelligence services in 2021, initial investigations by the prosecutors failed to provide answers and, to date, no individual or authority has been held responsible for these attacks on journalistic privacy and source protection. Unjustified national security justifications have been used to shield the responsible state institutions from accountability, resulting in a state of impunity.

Beyond such surveillance, the partners also discussed the threat of Distributed Denial of Service (DDOS) attacks, a form of digital censorship which left the websites of more than 40 different media offline for several hours after a spate of attacks in recent years. Although police arrested an individual they claim is responsible earlier this year, it is unclear when they will face trial and questions remain over whether the cyber-attacks were carried out with external coordination and resources.

The Platform partners note that after the mission ended, the Hungarian portfolio of Ringier, a Swiss media company, which includes the most popular tabloid, Blikk, was purchased by Indamedia, a pro-government media group. The acquisition, made ahead of next year’s election, is yet another example of the consolidation of media under ownership of private business interests close to the government and looks likely to further erode media pluralism in Hungary ahead of the vote.

Despite severe pressures on media freedom, quality and independent journalism continues to exist in Hungary and a cohort of outlets maintain a strong commitment to fact-based, public interest reporting. This is reinforced by high-levels of public support, which has translated to significant subscription funding and solidarity when an outlet is targeted. However, these outlets continue to face sustained economic, political and legal challenges and their foothold remains extremely fragile.

The platform delegation included representatives from the Platform secretariat, ARTICLE 19, Committee to Protect Journalists, European Broadcasting Union, European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, European Federation of Journalists, Index on Censorship, International Federation of Journalists, International Press Institute and Reporters Without Borders.

Prior to the commencement of the mission, partners reached out to organise meetings with the Prime Minister and the SPO. On behalf of the Prime Minister, Zoltan Kovacs confirmed that he was unavailable to meet due to prior commitments, while the partners never received a response from the SPO.

Signed by:

Index on Censorship

ARTICLE 19

International Press Institute (IPI)

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

Justice for Journalists Foundation

Committee to Protect Journalists

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Rory Peck Trust

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

PEN International

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

7 Nov 2025 | News

Today the Tackling Transnational Repression in the UK Working Group, which Index co-founded, sent a letter to the Home Secretary, Rt Hon Shabana Mahmood. It was in response to the UK Government’s disappointing and underwhelming response to the report produced by the Joint Committee on Human Rights looking at

the threat of transnational repression to those based in the UK.

Without more transparency and an approach anchored in the experiences of targeted communities in the UK, we cannot offer the protection and supported needed by those targeted for speaking out in the public interest. You can download the letter

here or read it below.