Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Farida Shaheed

Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights

Mónica Pinto

Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers

David Kaye

Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression

Seong-Phil Hong

Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention

Special Procedures Branch

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

United Nations Office at Geneva

8-14 avenue de la Paix

1211 Geneva 10

Switzerland

Dear Special Procedure mandate holders,

We are writing to urge you to pay continuing attention to the arbitrary arrest, detention, and conviction of the Qatari poet Mohammed al-Ajami, widely known as Ibn al-Dheeb.

Al-Ajami’s case has been the subject of a December 2012 communication to the government of Qatar from the Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights, the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, and the Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers1, discernable steps to address the issues set forth in the communication.

The arrest of Mohammed al-Ajami for the contents of his poetry is a violation of his right to freedom of expression and his right not to be arbitrarily deprived of liberty, and his conviction to 15 years in prison results further from a violation of his right to a fair trial. Amnesty International considers him a prisoner of conscience and he should be released immediately and unconditionally.

Various UN mechanisms have addressed al-Ajami’s case, as well as the human rights situation in Qatar more generally. Shortly before al-Ajami’s conviction in November 2012, the UN Committee against Torture criticized violations of due process by the State of Qatar in its consideration of the country’s second periodic report.2 The Committee recommended that Qatar “promptly take effective measures to ensure that all detainees, including non-citizens, are afforded, in practice, all fundamental legal safeguards from the very outset of detention.” It also expressed concern that persons detained under provisions of the Protection of Society Law (Law No. 17 of 2002), the Law on Combating Terrorism (Law No. 3 of 2004),and the Law on the State Security Agency (Law No. 5 of 2003) “may be held for a lengthy period of time without charge and fundamental safeguards, including access to a lawyer, an independent doctor and the right to notify a family member and to challenge the legality of their detention before a judge.” The Committee specifically cited Mohammed al-Ajami as an example of the fact that persons detained under these laws are often subject to incommunicado detention or solitary confinement. Though the Committee urged Qatar to amend its laws and ensure that fundamental safeguards are provided, Qatar has not taken any steps to address these concerns.

As noted above, al-Ajami’s case received additional attention from special procedures of the Human Rights Council through a joint communication issued on 21 December 2012, shortly after his original sentencing. The Special Rapporteurs in the Field of Cultural Rights, on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, and on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression expressed concern in a joint communication to the Qatari government that the arrest, detention, and sentencing of al-Ajami may have been “solely related to the peaceful exercise of his right to freedom of opinion and expression.” The Special Rapporteurs further noted concerns regarding the fairness of his trial and his treatment while in detention.3

On 14 February 2013, the Qatari government responded to the UN human rights experts by asserting that the government followed the proper procedures throughout al-Ajami’s case, and that the State “[keeps] in mind [its] obligations under international conventions and standards related to human rights and their 1 but the Government of Qatar has thus far not taken any implementation.”4 We believe that the Qatari government’s response did not accurately represent the administration of justice in this case, and the authorities took no further action of which we are aware.

On 8 January 2013, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) again voiced concern over the situation of Mohammed al-Ajami. The OHCHR’s spokesperson told reporters: “We are concerned by the fairness of his trial, including the right to counsel.” She additionally pointed to allegations that al-Ajami’s initial statement may have been tampered with in order to wrongly incriminate him.

In 2014, during a review of its human rights record in the context of the Universal Periodic Review, the Government of Qatar expressly rejected a recommendation to release Mohammed al-Ajami.5 At the same session, the government pointedly accepted a recommendation to “continue and strengthen relations with OHCHR.”6 We urge you to remind the Qatari government of this commitment.To the best of our knowledge, the United Nations has not taken any action on Mohammed al-Ajami’s case since his final appeal in October 2013. Thus, we respectfully ask that you continue to dedicate attention to his case and follow up on his arbitrary imprisonment, and insist that Qatar take corrective action to address the human rights violations that have been committed against him. We also ask that you raise these concerns with the Government of Qatar and follow up on the unaddressed recommendations set forth in past communications.

While we understand that his treatment while in prison has been generally acceptable, it remains the case, in our view, that he has been unfairly tried and convicted and, for that reason, this is a matter of an ongoing injustice.

Thank you for your time and consideration. Please do not hesitate to contact us if you need more information or clarifications.

Yours sincerely,

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain

Amnesty International

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information

Article 19

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

English PEN

FreeMuse

German PEN

Index on Censorship

International Federation for Human Rights

Irish PEN

PEN American Center

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders

Salam for Democracy and Human Rights

Split This Rock

Background

State security officials summoned Mohammed al-Ajami to a meeting on 16 November 2011. Upon arrival, authorities arrested him on suspicion of insulting the Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, and “inciting to overthrow the ruling system.”

The charges against al-Ajami related to a 2010 poem (“The Cairo Poem”) he had recited and which the Qatari authorities allege to have criticized the Emir. The poem nevertheless referred to the Emir as “a good man” and expressed “thanks” to him, and it formed part of a ‘call-and-response’ type of exchange that is a popular form of recitation. Al-Ajami recited it during a private gathering in Cairo in August 2010, after which one of the attendees posted a video of the event online.

On 29 November 2012, a lower court sentenced al-Ajami to life imprisonment following an unfair trial. The court reportedly heard testimony from three “poetry experts” employed by the government’s culture and education ministries, who testified that the poem represents an insult to the Emir of Qatar and his son.

On 25 February 2013, an appeals court reduced al-Ajami’s life sentence to 15 years. The Court of Cassation, Qatar’s highest court, upheld the 15-year sentence on 20 October 2013. Al-Ajami’s only remaining path to freedom is a pardon from the Emir.

The administration of justice in this case has been grossly flawed and has resulted in the arbitrary detention of Mohammed al-Ajami.

We believe that the legal basis of the charges against Mohammed al-Ajami – based in Articles 134 and 136 of the Qatari Penal Code – do not constitute internationally recognizable criminal offenses, unlawfully restrict the right to freedom of expression, and expressly contradict Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which states that: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

The authorities held him for a prolonged period of pre-trial solitary confinement. Following his arrest on 16 November 2011, Mohammed al-Ajami was held incommunicado for three months before he was allowed visits from his family. The first trial session was held in March 2012. Throughout the pre-trial investigations and despite petitions to the judge about his treatment, he was held in solitary confinement in a very small cell.

While he was being held in solitary confinement, authorities forced al-Ajami during interrogations to sign a document falsely stating that the poem was read in a public place in the presence of the press, according to information available to our organizations. In November 2011 and, reportedly, in subsequent court sessions, the lawyer of Mohammed al-Ajami asserted to the court that the poem was recited only in private.

We are concerned that the period of pre-trial detention without charge may have exceeded even Qatar’s own laws. Court documents indicate that the duration of pre-trial detention was within the limits provided for in Qatari law – which allows, in specific circumstances, up to six months detention before trial.

However, Mohammed al-Ajami’s former lawyer indicated in writing that the period of pre-trial detention exceeded the six months provided for in law. He indicated that charges had first been set out in June 2012.

Our organizations are unable to resolve this contradiction. We urge the Special Procedures branch to investigate these competing claims.

The trial was held behind closed doors without legal basis, and the court disregarded Mohammed al-Ajami’s right to choose his own legal representation by its imposition of another lawyer in place of the one he had chosen.

There was a lack of separation of investigative and decision-making powers, infringing on the principle of impartiality. According to information available to the signatories, Mohammed al-Ajami’s lawyer requested at the first session of the Doha Criminal Court that the presiding judge exclude himself from the case as he had conducted the pre-trial investigation. The judge rejected the lawyer’s request.

Al-Ajami was denied the right to be present at the trial. During the final hearing in October 2012, the court expelled Mohammed al-Ajami for being unruly. In his absence, and without measures taken to preserve the rights of the defense, the court proceeded to schedule the judgment to be held on 29 November 2012. Mohammed al-Ajami was not informed of the date. On the day of the verdict, the prison authorities did not bring Mohammed al-Ajami to court. Nevertheless, according to sources who informed al-Ajami’s former lawyer, the judge pronounced to the court “on the attendance of Mohammed al-Ajami, we have sentenced him to life.”

State security officials in Qatar continue to detain people in the absence of due process under laws that increasingly contribute to an environment that stifles and criminalizes expression. Mohammed al-Ajami is just one of the victims of this political reality. The international community should not ignore this violation of the right to freedom of expression or the failure to ensure fair trials in Qatar.

1 The letter, dated 21 December 2012, is referenced AL Cultural rights (2009) G/SO 214 (67-17) G/SO 214 (3-3-16); QAT 1/2012 and can be accessed at https://spdb.ohchr.org/hrdb/23rd/public_-_AL_Qatar_21.12.12_(1.2012).pdf

2 See: Committee against Torture: Concluding observations on the second periodic report of Qatar, adopted by the Committee at its forty-ninth session (29 October-23 November 2012), 25 January 2013, UN reference: CAT/C/QAT/CO/2

3 The letter, dated 21 December 2012, is referenced AL Cultural rights (2009) G/SO 214 (67-17) G/SO 214 (3-3-16); QAT 1/2012 and can be accessed at: https://spdb.ohchr.org/hrdb/23rd/public_-_AL_Qatar_21.12.12_(1.2012).pdf

4 Referenced 532 and QAT 1/2012, the letter can be accessed at: https://spdb.ohchr.org/hrdb/23rd/Qatar_14.02.13_(1.2012)_rescan.pdf

5 See paragraph 125.7 of the Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review – Qatar, issued by the Human Rights Council at its twenty-seventh session, dated 27 June 2014, is referenced A/HRC/27/15.

6 See paragraph 122.16 of the UPR report.

Freedom of speech clashing with commercial concerns has been an ongoing theme for many media and internet companies operating on an international stage, but it’s rare that a country’s liberal approach to expression is presented, in itself, as a prime investment opportunity.

Now Qatar, the richest country in the world, is positioning itself as a liberal alternative to the other resource-rich Gulf states – as revealed in an op-ed by the CEO of a premier London-listed Qatari investment fund.

The chairman of the Qatar Investment Fund PLC, Nick Wilson, authored an article this week on ArabianBusiness.com, claiming the country “has a habit of pushing its progressive agenda, to the irritation of its more conservative neighbouring states elsewhere in the Gulf Co-operation Council.”

Qatar Investment Fund manages approximately £200m in assets – investing into Qatari equities and employing dozens of fund managers. Its website trumpets Qatar as one of the worlds fastest growing economies, as well as pointing to its hugely lucrative gas exports.

But in this piece, the investment managers emphasised a different aspect of Qatar – the the “liberal minded” Al Jazeera TV network and an apparent commitment to free speech, especially when compared with its Gulf neighbours.

“We’ve seen the consequences of blocking access to information in other countries of the region.”

“Qatar is a bastion of free speech – and the flow of information should help to create a benign environment for investors.” he added.

The piece also pointed towards progressive women’s rights in Qatar, noted the political unpredictability of the region, but concluded that Qatar was “less frightened of change,” and “safe for business.”

As Wilson mentioned, Qatar now faces an unprecedented rift with the other GCC members – in particular Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and UAE who dramatically withdrew their envoys from Doha recently. He noted that Qatar had not withdrawn their envoys in retaliation, suggestive of their “liberal” tendencies.

But Qatar’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood both in Egypt and the Gulf, has set it contrary to GCC security policy – with UAE and Saudi Arabia having designated the Brotherhood “a terrorist organisation.”

And Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a provocative Islamist preacher and key Muslim Brotherhood member, is based in Doha. He presents a weekly show and sermon on the Arabic version of Al Jazeera, reportedly watched by 20 million viewers.

The outspoken preacher recently incensed the UAE by denouncing the Emirates political policies as “un-Islamic,” in response to an Islamist crackdown orchestrated by UAE’s sophisticated state security apparatus.

Qatar, as Wilson noted in his article, has irked its neighbours by allowing al Jazeera, al Qaradawi and the Muslim Brotherhood to be supported by Qatar’s extensive financial resources.

It now faces potential sanctions from Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain has even called for the GCC to be split up – unless Qatar shuts down the al-Jazeera TV network, ejects al-Qaradawi and stops support for Islamists.

While secretive Qatar is keen to maintain its supportive stance of the Brotherhood, it’s unclear whether freedom of expression comes into play or if there are wider geopolitical considerations at play.

More likely it is the latter – analysts reaction to the Qatar Investment Fund’s glowing appraisal of Qatar’s “liberal” values has been muted.

“Qatar may be a freer society than some of it’s neighbours, but this is hardly a useful measure,” says David Wearing, a PhD candidate and Gulf Expert at SOAS University in London.

“Objectively, it is an autocratic monarchy; not liberal, and certainly not democratic. Some space exists in Qatar for criticism of other regional governments, but not of the Doha regime itself.”

Wearing pointed to the case of Mohammed al-Ajami who was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment in October 2013, for “insulting the emir.”

Nader Hassan, a professor at the University of South Alabama, thinks the op-ed may fit into a broader PR narrative which is sanitising Qatar’s human rights reputation.

“Qatar has been playing a very skillful public relations game,” he told Index, “portraying itself as a beacon of free speech and press freedom in the region.”

“Compared to its more powerful neighbor, Saudi Arabia, this may be true. However, there are significant restrictions on press freedom in Qatar.

“Al Jazeera, for example, almost never carries any critical pieces on Qatar, such as the abuse of migrant workers.”

Hassan admitted that some Al Jazeera pieces favoured openness and journalistic professionalism- but concluded that calling the network “liberal” was “far from the truth.”

This article was posted on 21 March 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

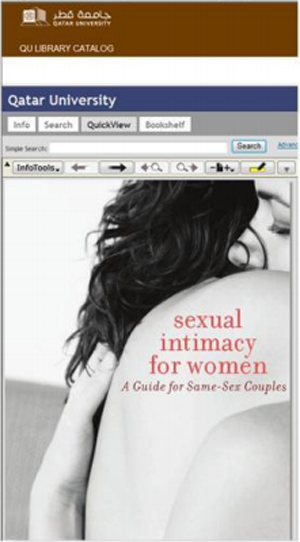

A group of students at the University of Qatar have started a petition to remove “inappropriate” books from the university library.

A group of students at the University of Qatar have started a petition to remove “inappropriate” books from the university library.

In a message circulated online, the students state that:

These books which are available with a click of a button call for adultery and homosexuality; they also represent the sin for the youth to seduce them and ruin their morals…We hope that people with conscience would move to get rid of such administrations who brought corruption upon our educational institutions.” (PDF: Arabic)

While specific books were not mentioned, the petition included book covers featuring female nudity.

The university responded with a statement explaining that titles are automatically added to the library through subscriptions to foreign and international publishing houses. They are planning to form a committee to prevent this from happening again, and have put in place a “censoring policy” to be able to “delete the books which are against our culture according to clear standards before they reach the library’s index.”

ASwiss television channel claimed on 18 April that two of its reporters were detained without charge in Qatar for 13 days. The RTS network alleges that the pair were in the country to shoot a documentary about Qatar hosting the World Cup in 2022. The two, a journalist and a cameraman, were allowed to return to Switzerland on Friday (15 April) after paying a court ordered fine.