Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103683″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]The head judge cleared his throat and called the journalist. As soon as he pronounced her name, “Seda Taşkın,” in his high-pitched voice, a look of incredulity spread across the faces of the handful of people watching the trial in the austere courthouse in Muş, a small town in Turkey’s far east. One lawyer, startled, dared to point out the unexpected sequence of words: “Did you just call her ‘Seda?’” Rıdvan Konak asked.

For the first time throughout the trial, the judge’s impassive eyes betrayed a glimpse of nervousness. It must have dawned on him: During the previous hearings, he had insisted on calling her “Seher,” the name on her ID card. After all, the prosecution had claimed that “Seda” was nothing but a code name for her allegedly illegal activities. In fact, Taşkın’s purported code name was the sole shred of ostensible evidence for the prosecution’s charge of “membership in a terrorist organisation,” and the judge was absent-mindedly throwing it away.

A faint and uneasy smile formed below his thin moustache. “You thought all along that we were fixated on that, but we were not,” he managed to reply, looking awkwardly at lawyers from his raised platform. It was an explanation he mumbled aloud twice – just like a little boy caught in flagrante delicto trying to convince his parents that he wasn’t misbehaving. It was also an odd excuse given that the court had twice refused to release the journalist on the grounds that more evidence was needed to prove that all her family and friends had called her “Seda” since she was a toddler. Yet a hopeful question popped up in everyone’s mind. Could this slip of the tongue be a good omen?

The fact the head judge so naturally ended up calling the journalist by the name everybody used showed how much regard the court paid to the accusations levelled by the prosecution. The journalist’s lawyer, Ebru Akkal, said distorted evidence and interpretations were common in free speech cases. “But in Seda’s case, we are dealing with blatant lies,” Akkal said. Taşkın, a reporter focusing on culture, education and women’s rights, was accused of sharing articles on her social media accounts – none of which were written by her.

“Let’s imagine for a moment that they were claiming that Seda killed someone. But the prosecutor is unable to present the weapon with which the crime was committed or establish the place where the murder occurred,” Akkal explained. “What’s more, the person whom they claim was killed is not dead but stands before them. This is the kind of case that Seda was faced with.”

And it did feel as though Taşkın was being personally targeted by the anti-terrorism unit of Muş in light of the massive rights violations she experienced from the moment of her arrest, including a fabricated tipoff, physical and psychological ill-treatment during custody, threats, as well as blackmail.

Nevertheless, Akkal said they expected Taşkın’s release until the very moment that the verdict was pronounced. The judges overseeing the case, however, opted to change the goalposts at the last minute, suddenly and arbitrarily replacing the original accusation with the vaguer charge of “aiding a terrorist organisation without being a member.” The court also refused to provide any additional time to the defense to object to the charge as required.

“I think that the court was convinced that Seda had nothing to do with a terrorist organisation. But they needed to find a charge because they couldn’t let any individual who got into the authorities’ grip go without a sentence,” Akkal said.

The court eventually handed Taşkın four years and two months on the charge of “aiding a terrorist organisation without being a member” and three years and four months on the charge of “conducting propaganda,” adding up to a total of 7.5 years in jail. The journalist, who has already spent 10 months in pre-trial detention at the Silivri Prison in Ankara, will remain in jail during the appeal process. Taşkın was forced to make all her defense statements via video-conference broadcast on a screen inside the courtroom 1,000 kilometers from the capital.

The court had already buried police irregularities by refusing to investigate the identity of the person who gave the tipoff despite repeated requests by lawyers. The extension of the email address in the files, which authorities neglected to black out, clearly indicated the tipoff came from a member of the police department. The judges also refused to heed Taşkın’s long account of the abuse, strip searches, beatings and threats she suffered. But by sentencing her, they have closed the case with a minimum of fuss for the police and the prosecutor.

Taşkın’s lawyers expressed indignation at the court’s handling of the case, describing it as blatant bias. “If the judges are to wash the prosecutor’s hands and the prosecutor, in turn, the police’s hands, why not just let the police run the investigation and issue a verdict?” Akkal said.

“Eclectic and sensitive”

Only two years ago, Taşkın was thrilled when she learned that she had been appointed to the eastern city of Van by the pro-Kurdish Mezopotamya News Agency. She thought that her new position in the agency’s second largest regional office would give her invaluable experience as a journalist in a much tougher environment. The decision also meant leaving her family home in Ankara for the first time in her life. Her parents, however, were concerned about her plans, since journalists working in Kurdish provinces have become even more vulnerable to arrests and detentions since authorities declared a state of emergency in 2016.

She possibly chose the most difficult context possible to work “in the region,” as many reporters in the field refer to the Kurdish southeast. The crackdown on Kurdish media intensified during a military assault that was launched in the winter of 2015 and peaked under the state of emergency clampdown. Many journalists were tracked, investigated, threatened and some, such as Nedim Türfent, jailed and charged with terrorism offenses.

Ultimately, Taşkın’s motivation and determination won her family over, and the young journalist went to begin her work.

The poise she showed was a pleasant surprise for her elder sister Yelda. “We saw the change,” she says. “Seda is someone very emotional and restless. Although she tried, she didn’t graduate from university. So, Seda started as an intern at the agency and was hoping to study journalism after garnering some experience.”

In Van, she felt empowered to express her personality, especially when covering stories that were colourful or touching more so than merely political. “She was eclectic. Her sensitivity and inner conscience allowed her to report on universal subjects such as ecology or women’s issues,” her sister said. She toured villages around the Van Lake, met local people and developed her passion for photography to such a degree that she didn’t want to go back to Ankara.

Then, one day in December 2017, her agency sent her to Muş to report on as many articles as she could. It was Taşkın’s first time in the rural and conservative province. She travelled first to Varto, a former Armenian town populated today by a majority of Alevis – a community whose belief system is often labelled as a heterodox and progressive form of Shia Islam – who had fled Dersim during the state-perpetrated massacres of 1938. Dersim, today called Tunceli after the name of the Turkish state’s military operation, is also the hometown of Taşkın’s family.

After reporting on the newly established culture and solidarity association in Varto, she returned to the provincial center, a place firmly under the control of the police. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) had won the municipality over the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) and kept the city under strict state authority. She would be arrested shortly thereafter.

Bizarre significance of hearing dates

According to her lawyer Akkal, the mere fact that proceedings were conducted in Muş seriously affected the course of the trial. “The rulings of courts are so inconsistent and unpredictable. Had Seda been arrested in Ankara she wouldn’t even have stayed in prison a day. At worst, she would have been released at the first hearing,” Akkal said. “A very different approach exists in places such as Muş, Bitlis or Van. People are declared guilty at the moment they are arrested. [Authorities] don’t follow the evidence to find the suspect, they collect the evidence based on the suspect instead.”

Taşkın’s case followed the same trajectory. Among the several reports she was covering, Taşkın met with the family of 80-year-old Sise Bingöl, who has been in jail on terror charges since 2016 despite suffering from heart and lung disease. The recordings of her interview with Bingöl’s relatives, which were found after Taşkın was arrested, were used as evidence in the trial even though the journalist never published them. Once she was taken in custody, police seemed to have dissected her Facebook and Twitter accounts to find any post that could make a terrorism charge admissible in the eyes of the Turkey’s ever less independent judiciary.

Taşkın’s former colleague Hayri Demir, a journalist based in Ankara who followed the last hearing in Muş, stressed that social media posts containing news reports should be considered as a journalistic activity in itself. “Social media has become a publishing space for journalists. It’s a space where journalists share their own and their colleagues’ articles,” said Demir, who himself is facing 10.5 years for five tweets – all of which lacked any personal comment – on Turkey’s military operation against the Syrian town of Afrin in January.

“It’s six days per character,” he joked. “They are trying to entirely silence journalists by even incriminating their social media posts.”

Accusing journalists of sharing other people’s news articles also violates the individuality of criminal responsibility, a critical principle of modern criminal law.

But aside from the dubious practices of the authorities, there was one aspect to Taşkın’s case that seemed to amount to psychological harassment: The symbolic dates of the hearings. The second hearing of the case was held on 2 July, the 25th anniversary of an attack by an extremist mob in Sivas that killed 33 Alevi artists. The third hearing was set on 12 September, the anniversary of the 1980 coup, which resulted in imprisonment and torture for thousands of left-wing and pro-Kurdish activists. The fourth and last hearing was on 10 October, the third anniversary of Turkey’s deadliest-ever terrorist attack, which the Islamic State perpetrated against peace activists in Ankara. As for the date of the first hearing, 30 April, that happened to coincide with the liberation of Muş from foreigners after World War I.

The journalist was the first one to notice the significance of the dates, Akkal said. “She told me, ‘Ebru, they are doing it intentionally.’ I don’t believe that the dates were randomly chosen either.”

The verdict will become definitive if the regional court rejects her appeal – and because Taşkın’s sentences are each under five years, she will not have recourse to the Supreme Court of Appeals if the lower court rules against her. Regional courts are hardly known for their initiative, but both lawyers and taşkın retain their hopes for a rare fair reassessment of the case. In the meantime, lawyers have applied to the Turkish Constitutional Court to halt the execution of the sentence based on a precedent for journalists Mehmet Altan and Şahin Alpay. In January 2018, the Constitutional Court ruled that the imprisonment of both journalists not only violated their right to security and freedom but that there was not enough evidence to hold the men. Although first instance courts controversially refused to implement the decision, the pair was released at the end of a legal row months later.

Taşkın’s lawyers are also preparing to file an application at the European Court of Human Rights, although Akkal noted that it will take at least a year for either of Turkey’s top courts to make a decision. Taşkın, meanwhile, may face years in prison waiting for justice to be served. “After the initial shock of the verdict, she is now calm. She is trying to spend her time productively,” Akkal said.

Her sister Yelda said Seda had started to learn English in prison and was reading lots of books. “We were expecting her to be released in each hearing. But we would like anyone who is unfairly imprisoned to be free,” she said, adding that Seda has tried to remain conscious of the fact that she is not the only journalist in jail.

Indeed, during her defense, Taşkın not only called for her release but expressed her wishes that all her colleagues would walk free – an expression of human solidarity against organised unlawfulness that has riddled the law, one unjust sentence at a time.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1542196485676-71e5a902-cafb-4″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”81952″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]While the scale of Turkey’s crackdown on freedom of expression in the post-coup-attempt emergency rule era has been intense, the assault on dissenting voices predated the failed putsch.

Whether it they were Kurdish writers at the turn of the decade, or worked for Feza Publications just months before the night elements of the military betrayed their fellow Turks, journalists that offered alternative viewpoints were long in president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s crosshairs.

In the case of Feza’s popular publications — among them Zaman and the English-language Zaman Daily — which had been raided and its employees arrested on several occasions since 2014 as the shakey rule of law eroded in Turkey. In a March 2016 move that was condemned internationally, Feza Publications was targeted with the imposition of government-appointed trustees. This resulted in the termination of hundreds of media professionals from journalists to advertising reps and the literally overnight change from independent and critical outlets to government propaganda sheets.

An appeal on the takeover of Feza was made to the European Court of Human Rights to address a clear violation of the right to freedom of expression, among others. Yet the application was rejected on what was seen as questionable grounds, becoming one of the many disappointing decisions taken by the international court.

Takeover

The assault on Feza Publications was ordered by the Istanbul 6th Criminal Court of the Peace on Friday 4 March 2016. By nightfall, the police had raided the Zaman newspaper office, using tear gas and water cannons on the protestors outside. The Saturday edition of Zaman was the last version of a free newspaper. The front page headline declared “the constitution suspended” and noted that Turkish press had seen one of its “darkest days”. The Sunday edition, under new ownership, was a disconcerting contrast. The front page showed a smiling president Erdogan holding hands with an elderly woman, coupled with an announcement that was he hosting a Women’s Day event. The main headline was “Historic excitement about the bridge”, a reference to a span being built across the Bosphorus with state funding.

Newly appointed government trustees immediately interfered with editorial decisions. A staff member commented that: “Before the takeover, our deadline was 7:30pm. The trustees moved that deadline to 4:30pm, and in the remaining three hours they censored and changed the paper to fit their new ‘line’.” The new management had also banned staff access to the newspapers’ archives.

The police who had raided the office on the Friday, stayed on to check staff IDs and prevent groups of three or more from assembling. Hundreds of Feza Publications employees were then dismissed under Article 25 of the Turkish labour law which lays out that contracts can be annulled without prior notice if an employee displays “immoral, dishonourable or malicious conduct”. Those dismissed have recounted how they received a generic letter which gave no explanation the accusations.

Considered enemies of the state, former Feza Publications employees found it difficult to obtain new jobs. They were left to survive on little to no income; Article 25 outlines that those dismissed are not eligible for redundancy packages or other compensation And recruiters were right to be weary; four-and-a-half months after the takeover, the July 16th coup attempt occurred, and purges began on a massive scale. Thousands of journalists were dismissed, and dozens were detained on terrorism-related charges. Feza Publications, already marked as Gulen-linked and thus terrorist – without the presumption of innocence – during the takeover, was a prime target. Thirty-one Zaman employees are currently standing trial, with nine, including Şahin Alpay, facing life sentences. In January 2018, Turkey’s constitutional court ordered that Şahin Alpay, alongside journalist Mehmet Altan, be released from pre-trial detention.

After the lower courts refused to comply, the ECtHR ruled that their detention was unlawful and that they should each be compensated €21,500.

The other journalists, unable to garner the same international support, have remained in pre-trial detention. Zaman’s Ankara chief Mustafa Ünal, arrested purely because of his newspaper columns and facing the same circumstances as Alpay, has also applied to the ECtHR. But his application was rejected, and after almost two years behind bars he expresses in despair “my scream for justice has faded away in a bottomless pit”. He is not alone, with the ECtHR and international community doing little in light of the Feza Publications debacle and abolishment of the freedom of expression in Turkey.

Appeal to the ECtHR

The Feza Publications takeover and ensuing rights violations, on top of individual pleas for justice, has led to appeals for the entity itself. Two shareholders of Feza Gazetecİlİk A.Ş. (the Feza stock company) took the matter of government-appointed trustees to the Turkish constitutional court. When this appeal failed, they applied to the ECtHR regarding violations of: Article 10, right to freedom of expression; Protocol Article 1, right to property; Article 7 and 6.2, no punishment without law and presumption of innocence; and Article 8, respect for private and family life. Dated 29 July 2016, the application was rejected by ECtHR Judge Nebojsa Vucinic on 14 December 2017 with reference to the Köksal v. Turkey decision.

The decision is reference to a case surrounding Gökhan Köksal, a teacher and one of over 150,000 dismissed from their jobs after the coup attempt. The ECtHR had rejected his appeal on the basis that he must first apply to the Turkish State of Emergency Commission, i.e., first exhaust all domestic avenues. The Köksal decision was problematic. The State of Emergency Commission was established in January 2017 for appeals against dismissals and closures assumed under the state of emergency imposed since 20 July 2016. To date, the Commission has only approved 310 out of 10,010 finalised cases, a 3% success rate. There are almost 100,000 cases still under examination. Many consider the mechanism to be inefficient, and its impartiality questionable. It should not be considered a reliable domestic avenue. Reference to the State of Emergency Commission in relation to Feza Publications poses a further problem; the appointment of government trustees occurred four-and-a-half months before the state of emergency was implemented.

The ECtHR decision is completely inadequate. Although some Feza employees were dismissed under state of emergency decrees, other dismissals and violations pertaining to the Human Rights Convention commenced well before. Although all Feza media outlets (Zaman and Zaman Daily, the Cihan News Agency, Aksiyon magazine, and the Zaman Kitap publishing house) were closed via emergency decree in July 2016, Feza shareholders are not entitled to apply to the State of Emergency Commission. Only persons in charge of the legal entities or institutions at the time of closure – by that point, the government appointed trustees – have the right to apply. Such a situation is implausible, leaving the ECtHR as the only option. Besides, it has been shown that regardless, neither the State of Emergency Commission nor the Turkish judicial system should be considered viable domestic avenues to appeal rights violations.

This ECtHR decision, one in a long line of disappointing rulings for Turkish victims, is seriously flawed. The ECtHR must reconsider the Feza Publications application, alongside those such as Köksal v. Turkey which only pave the way for future rejections. Without adequate ECtHR rulings there is little hope for the upholding of human rights, such as freedom of expression, in Turkey.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100019″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]In the wake of the 15 July 2016 coup attempt, Turkey has become a “de facto permanent” emergency regime. The state of emergency, which has been extended six times, has become a convenient pretext for the government to crack down on freedom of expression.

The resultant purge has had draconian impacts: 5,822 academics sacked, 189 media outlets shuttered and 319 journalists arrested or prosecuted. The country’s judicial system has been decimated, with 4,560 judges and prosecutors dismissed. The government’s near-complete takeover of the judiciary and its direct defiance of the rule of law has debased freedom of expression in the country.

Examples of how the executive arm of the Turkish government is pulling the strings of the judiciary are not hard to find.

“Public indignation”

On 31 March 2017, the chief judge and two members of the Istanbul 25th High Criminal Court, who ordered the release of 21 journalists, and the prosecutor, who requested the releases, were suspended and later faced a disciplinary hearing. The 21 journalists were kept waiting in a prison van until a new arrest and detention order was issued by another court, which was under an onslaught of attacks from pro-government social media accounts.

Judicial Council deputy president Mehmet Yilmaz explained the reasoning behind the suspension of the judges: “The evidence has not been collected…and the release decision issued…has caused public indignation and harmed public conscience.”

If members of the judiciary can be suspended because their decision has caused “public indignation and harmed public conscience”, this suggests that judges in Turkey are without any protection from external pressures.

In another case, on 31 January 2018, a court ordered the release of Amnesty International’s Turkey chair Taner Kilic, but just hours later another demanded his re-arrest. Amnesty’s secretary general Salil Shetty said: “Over the last 24 hours, we have borne witness to a travesty of justice of spectacular proportions. To have been granted release only to have the door to freedom so callously slammed in his face is devastating for Taner, his family and all who stand for justice in Turkey.”

Taner’s renewed detention came after a decision from the Istanbul trial court to conditionally release him before his trial. However, after the prosecutor appealed, a second court in Istanbul accepted this appeal and quashed Taner’s release.

“I do not know why I was imprisoned a year ago and why I was released”

In another example of government interference, Turkish-German journalist Deniz Yücel, who reported for Die Welt newspaper, was arrested on 27 February 2017 in Istanbul. At the time, Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, summarised the accusations against Yücel saying: “He is not a correspondent; he is a terrorist. … This person hid in German consulate for a month as a representative of PKK, as a German spy. We have recordings, everything. This is the very spy terrorist.”

Erdogan also reportedly said that Yücel would not be released so long as he was the president. Yücel’s detention continued for almost a year without charge.

On the eve of his official trip to Germany on 15 February 2018, prime minister Binali Yildirim responded to protests and open requests from the German government for Yucel’s release. He said: “I think that a development will take place soon.” In a joint press conference with German chancellor Angela Merkel on 15 February 2018, he said: “What is necessary shall be done within the scope of the rule of law; what is required of us is to clear the way for the courts. … I hope that the trial will take place within a short time and a result will be achieved.”

On 16 February 2018 the Istanbul High Criminal Court accepted an indictment against Yücel that sought an 18-year sentence, yet the court also simultaneously ordered his release. Yücel flew to Germany on the same day. No international travel ban was imposed, despite the high sentence the prosecutor was demanding, which is the regular practice in “terror” related cases.

After his release, Yücel reported that he was given a 13 February 2018 ruling by the Third Criminal Peace Judgeship which detailed an order for his continued detention. “I am free despite this. I do not know why I was imprisoned a year ago and why I was released today. Is it not strange? Anyway, it does not matter. After all, I know that neither my jailing — more precisely my being taken as a hostage a year ago — nor my release today is in accordance with the rule of law at all. I know this very well.”

It’s clear that Yücel’s release and ability to leave the country were the result of political deals and the high criminal court was taking orders from the executive branch of government.

“Attempting to overthrow the constitutional order”

Within hours after Yücel’s release, six other individuals, including five journalists, were issued life sentences for “attempting to overthrow the constitutional order”. Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan, Nazli Ilicak, Yakup Şimşek, Fevzi Yazıcı and Şükrü Tuğrul Özsengül were all handed sentences after being convicted of involvement with the attempted coup, despite a clear lack of direct evidence.

“The court decision condemning journalists to aggravated life in prison for their work, without presenting substantial proof of their involvement in the coup attempt or ensuring a fair trial, critically threatens journalism and with it the remnants of freedom of expression and media freedom in Turkey,” said David Kaye, the United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression.

The constitutional court decided on 11 January 2018 that the freedom of expression and liberty of the two journalists Mehmet Altan and Şahin Alpay had been violated. Following the decision, deputy prime minister and government spokesperson Bekir Bozdağ stated on his Twitter account that the constitutional court had overstepped its boundary drawn up by the constitution and legislation. Under pressure from the government, the decisions made in the cases of Alpay and Altan were not implemented by Istanbul courts. This was due to almost the same reasoning as used by the government spokesperson.

Despite the dictum that the court’s decisions are final and binding on the legislative, executive and judicial matters, the courts of the first instance have not implemented the decision.

Another disappointment for the freedom of all arrested journalists

In another case, after an application by journalist Sahin Alpay, the constitutional court delivered the decision on 19 March 2018 that found Alpay’s rights were violated under the European Convention on Human Rights. By contrast, the Istanbul court followed the ruling this time and issued Alpay’s conditional release. Surprisingly, nothing was heard from the executive on this occasion. This development has been regarded by some as the government’s tactical move to avoid a possible European Court of Human Rights ruling on related pending cases to the effect that the constitutional court is not an effective remedy.

Turkish human rights lawyer Kerem Altıparmak tweeted that the Turkish government’s move was intended to send a message to the ECtHR that the constitutional court is a viable domestic remedy. Yaman Akdeniz, another prominent law professor and rights defender, said that ECtHR’s rejection of examination of the cases of journalists relying on the Article 18 of the European Convention on Human Rights is another disappointment for the freedom of all arrested journalists.

“A disgrace to Turkey’s justice system”

On 9 March 2018 a Turkish court sentenced 25 journalists to imprisonment on the grounds of allegedly being members of a terrorist organisation. The prosecutor’s primary evidence was that the journalists had criticised the Turkish government and Erdogan on social media. On these charges, 23 of the accused journalists were given between two and seven years in prison. Nina Ognianova, the Committee to Protect Journalists Europe and Central Asia programme co-ordinator, described the decision as “a disgrace to Turkey’s justice system”. She called on authorities to drop the charges on appeal.

The judiciary’s exposure to outside influences and pressures have turned the Turkish judicial system into a nightmare for journalists, academics, rights defenders, philanthropists and even judges themselves.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524736212391-dfe96d06-6795-2″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” content_placement=”middle” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1521806157541{margin-top: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MMF_2017_web-cover.jpg?id=98589) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1521805928920{margin-top: 0px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Deaths” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

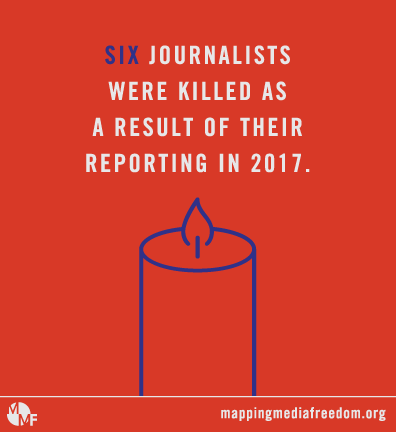

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Physical assaults and injury” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

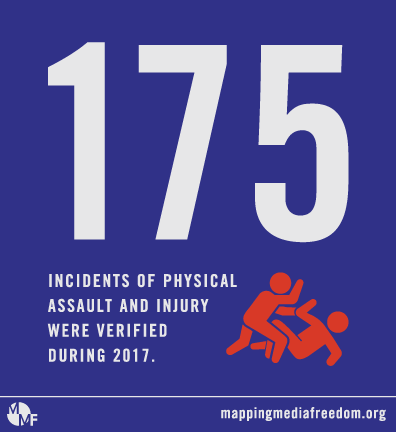

Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).

Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10). [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Arrests/Detainments” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July Afgan Mukhtarli was kidnapped from Georgia, where he had lived in self-imposed exile for three years, and taken to Azerbaijan. While in prison, he suffered serious health problems and lost a significant amount of weight. In January 2018 he was sentenced to six years in prison by an Azerbaijani court.

A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July Afgan Mukhtarli was kidnapped from Georgia, where he had lived in self-imposed exile for three years, and taken to Azerbaijan. While in prison, he suffered serious health problems and lost a significant amount of weight. In January 2018 he was sentenced to six years in prison by an Azerbaijani court. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Criminal charges/civil lawsuits” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. In Italy, lawsuits demanding millions of euros in damages were filed throughout the year. In March Claudio Riva, former owner of the steelworks company Ilva, sued newspaper Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno for €2.2 million in damages, for publishing an article about pollution allegedly linked to the company’s operations in Taranto. Riva’s lawyers asked for €550,000 in compensation for each of the four damaged parties: Riva Forni Elettrici SPA, Claudio Riva, Fabio Arturo Riva and Nicola Riva. In October Il Locale News was sued for €1 million by Giancarlo Guarrera, an engineer and director of Airgest, the company that manages Trapani airport in Sicily. On 8 November 2016 Il Locale News featured an article on financial issues at Airgest.

There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. In Italy, lawsuits demanding millions of euros in damages were filed throughout the year. In March Claudio Riva, former owner of the steelworks company Ilva, sued newspaper Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno for €2.2 million in damages, for publishing an article about pollution allegedly linked to the company’s operations in Taranto. Riva’s lawyers asked for €550,000 in compensation for each of the four damaged parties: Riva Forni Elettrici SPA, Claudio Riva, Fabio Arturo Riva and Nicola Riva. In October Il Locale News was sued for €1 million by Giancarlo Guarrera, an engineer and director of Airgest, the company that manages Trapani airport in Sicily. On 8 November 2016 Il Locale News featured an article on financial issues at Airgest. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Legal measures” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In the United Kingdom, the offshore company Appleby, which was at the heart of the Panama Papers scandal, launched breach of confidence proceedings against the Guardian and the BBC on 18 December, in an attempt to force them to disclose the documents used in the investigation. Appleby said the documents were stolen in a cyberattack and there was no public interest in the revealing of their contents.

There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In the United Kingdom, the offshore company Appleby, which was at the heart of the Panama Papers scandal, launched breach of confidence proceedings against the Guardian and the BBC on 18 December, in an attempt to force them to disclose the documents used in the investigation. Appleby said the documents were stolen in a cyberattack and there was no public interest in the revealing of their contents.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Job loss” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).

There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5). [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Intimidation” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

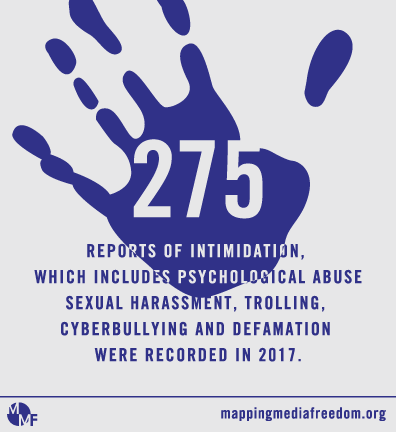

Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the BBC’s political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned a security detail at the Labour party conference in late September following online threats and abuse. The journalist attracted anger from some Labour supporters for her coverage of the 2016 Labour leadership race and the party’s poor performance in local elections, while a petition for her to be fired received 35,000 signatures.

Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the BBC’s political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned a security detail at the Labour party conference in late September following online threats and abuse. The journalist attracted anger from some Labour supporters for her coverage of the 2016 Labour leadership race and the party’s poor performance in local elections, while a petition for her to be fired received 35,000 signatures.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Attacks to property” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service. Her brakes had been cut and her anti-lock braking system was damaged. Zavialova called the police but, according to the journalist, they did not properly investigate the scene, failing to take fingerprints or full details of the damage.

There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service. Her brakes had been cut and her anti-lock braking system was damaged. Zavialova called the police but, according to the journalist, they did not properly investigate the scene, failing to take fingerprints or full details of the damage.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Blocked access” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.

There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Work censored or altered” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a concerted effort by press officers at the local council to control statements made by staff to journalists. Both complained that press officers were exerting pressure on staff to change statements that reflect badly on the council.

In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a concerted effort by press officers at the local council to control statements made by staff to journalists. Both complained that press officers were exerting pressure on staff to change statements that reflect badly on the council.[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”black” style=”dashed”][vc_column_text]

During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara. At a rally in Moscow on 26 March, police detained RBC correspondent Timofey Dzyadko, Mediazona publisher Piotr Verzilov, Open Russia correspondent Sofiko Arifdzhanova, Public Television of Russia journalist Olga Orlova, Echo of Moscow journalist Alexandr Pluschev and Kommersant-FM reporter Pyotr Parkhomenko. At the same rally, Guardian correspondent Alec Luhn was detained after he took a photo of a protester being arrested. He spent more than five hours at a police station without an explanation of why he was detained. Luhn was eventually charged with participating in an unsanctioned rally, even though he showed officers his press accreditation. At least nine media workers were detained across Russia on 8 October during further protests organised by Navalny.

During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara. At a rally in Moscow on 26 March, police detained RBC correspondent Timofey Dzyadko, Mediazona publisher Piotr Verzilov, Open Russia correspondent Sofiko Arifdzhanova, Public Television of Russia journalist Olga Orlova, Echo of Moscow journalist Alexandr Pluschev and Kommersant-FM reporter Pyotr Parkhomenko. At the same rally, Guardian correspondent Alec Luhn was detained after he took a photo of a protester being arrested. He spent more than five hours at a police station without an explanation of why he was detained. Luhn was eventually charged with participating in an unsanctioned rally, even though he showed officers his press accreditation. At least nine media workers were detained across Russia on 8 October during further protests organised by Navalny. Although the number of violations reported to Mapping Media Freedom that took place in Turkey decreased between 2016 and 2017 — from 231 to 135 — the country remains the number one jailer of journalists in the world with 151 media workers behind bars by the end of 2017. In all, 65 journalists were jailed and sentenced on charges including the spreading of terrorist propaganda. At the trial of journalist Nedim Türfent, who reported on security operations in Turkey’s Kurdish majority provinces, at least a dozen people claimed they were tortured by police.

Although the number of violations reported to Mapping Media Freedom that took place in Turkey decreased between 2016 and 2017 — from 231 to 135 — the country remains the number one jailer of journalists in the world with 151 media workers behind bars by the end of 2017. In all, 65 journalists were jailed and sentenced on charges including the spreading of terrorist propaganda. At the trial of journalist Nedim Türfent, who reported on security operations in Turkey’s Kurdish majority provinces, at least a dozen people claimed they were tortured by police. A total of 92 violations of media freedom were recorded in Belarus throughout 2017, including the detainment of 101 journalists. In all, 30 journalists received criminal charges. A wave of detentions occurred on the Belarusian holiday Freedom Day on 25 March, when 36 journalists were placed in custody. Olga Morva, Philip Warwick, Andrey Dubinin, Valery Shchukin, Katsiaryna Bakhvalava, Ihar Ilyash and Volha Davydava said they were beaten by police while under arrest. Warwick, from the United Kingdom, said he was denied the right to contact his embassy after being handcuffed and hit in the face; he spent over six hours at the police station. The apartment of journalist Maryna Kastylyanchanka, who works with human rights organisations, was searched. She was later jailed for 15 days for disobeying police and participating in the unsanctioned mass protests.

A total of 92 violations of media freedom were recorded in Belarus throughout 2017, including the detainment of 101 journalists. In all, 30 journalists received criminal charges. A wave of detentions occurred on the Belarusian holiday Freedom Day on 25 March, when 36 journalists were placed in custody. Olga Morva, Philip Warwick, Andrey Dubinin, Valery Shchukin, Katsiaryna Bakhvalava, Ihar Ilyash and Volha Davydava said they were beaten by police while under arrest. Warwick, from the United Kingdom, said he was denied the right to contact his embassy after being handcuffed and hit in the face; he spent over six hours at the police station. The apartment of journalist Maryna Kastylyanchanka, who works with human rights organisations, was searched. She was later jailed for 15 days for disobeying police and participating in the unsanctioned mass protests. In all, 74 violations against the media in Ukraine were reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. One of the most worrying trends included the treatment of foreign journalists or journalists working for Russian companies. Sixteen journalists were expelled from, or not allowed to enter the country, including some who worked for Russian state media outlets. There were three cases involving the abuse of Interpol warrants to arrest or detain foreign journalists in Ukraine by their countries of origin as a means of silencing critical voices. These were: Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Three journalists were arrested in territory controlled by self-proclaimed separatists in 2017, including Ukrainian blogger and writer Stanyslav Aseev, one of the few journalists contributing to western and independent media outlets in eastern Ukraine.

In all, 74 violations against the media in Ukraine were reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. One of the most worrying trends included the treatment of foreign journalists or journalists working for Russian companies. Sixteen journalists were expelled from, or not allowed to enter the country, including some who worked for Russian state media outlets. There were three cases involving the abuse of Interpol warrants to arrest or detain foreign journalists in Ukraine by their countries of origin as a means of silencing critical voices. These were: Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Three journalists were arrested in territory controlled by self-proclaimed separatists in 2017, including Ukrainian blogger and writer Stanyslav Aseev, one of the few journalists contributing to western and independent media outlets in eastern Ukraine. Between 2016 and 2017, media freedom violations in Spain increased from 56 to 66. Journalists experienced difficulties before, during and after the referendum on Catalan independence on 1 October. In July the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, based in Barcelona, refused to publish a column written by Gregorio Morán in which the journalist criticised the “corrupt” regional government of Catalonia. Morán also accused the Catalan media of receiving sums of public money, adding that it was therefore no surprise to see them supporting Catalan independence.

Between 2016 and 2017, media freedom violations in Spain increased from 56 to 66. Journalists experienced difficulties before, during and after the referendum on Catalan independence on 1 October. In July the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, based in Barcelona, refused to publish a column written by Gregorio Morán in which the journalist criticised the “corrupt” regional government of Catalonia. Morán also accused the Catalan media of receiving sums of public money, adding that it was therefore no surprise to see them supporting Catalan independence. [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1521129408155{background-color: #d5473c !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Protect media freedom”][vc_column_text]

We monitor threats to press freedom, produce an award-winning magazine and publish work by censored writers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521129253575{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MMF_2017_map-standalone.jpg?id=98665) !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_empty_space][/vc_column][/vc_row]