Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The Charlie Hebdo bombing exposes a gulf in understanding between the secular French establishments and Muslim immigrants, says Myriam Francois-Cerrah

The firebombing of Charlie Hebdo offices following its decision to run an edition featuring the prophet Mohammed as “guest editor”, is a sad reflection of France’s uneasy relationship to Islam and religion more generally.Sadly, there are some who do not believe that Charlie Hebdo should have the right to publish a satirical issue, in which it presents Prophet Mohamed as the inspiration of the Arab revolutions and subsequent rise of islamist parties in the region (regardless of the accuracy of this link!). They are no doubt in a minority, just as those who committed this crime will no doubt be revealed to be a fringe group or renegade individuals.

But there is no denying the fact many Muslims are offended by the decision to run an issue entitled “Charia Hebdo”, with reference to “100 lashings if you don’t die of laughter” (chuckle) and a “halal aperitif” (ha!) and perhaps more pertinently, to run images of Prophet Mohammed.

Charlie Hebdo is renowned for being a highly satirical outlet which pushes the limits of public discourse on any given issue through its provocative illustrations and irreverent style. It has in its time, been accused of being anti-Semitic, anti-Catholic and now Islamophobic to boot and would no doubt parade these accusations as badges of honour.

However the recent issue comes at a complex time in France’s political life. The far right has made large advances, gaining 15 per cent of the vote in recent regional elections and they have maintained the “immigration question” near the top of the political agenda, drawing parallels between Muslims praying in the street and the Nazi occupation. Meanwhile, recent stats suggest that amongst the descendants of immigrants, 70 per cent, compared with 35 per cent amongst recent immigrants, consider that the French government does not respect them, including amongst those possessing university degrees and thus in theory, more “integrated” into the social fabric.

French Arabs face unemployment at a rate of 14 per cent compared with 9.2 per cent amongst people of French origin — even after adjusting for educational qualifications and are poorly represented at every level. Charlie Hebdo’s decision to poke fun at Islam, although completely inline with its treatment of other issues, comes at a time of intense polemics over the place of Islam within France, as debates over “laicite” galvanise the political spectrum.

Many Muslims appear to feel under siege in a political climate which continues to view Islam as an impediment to full adhesion to French national identity and where religious practise is associated with a social malaise. Indeed, a recent report by the French academic Gilles Kepel has reignited debate over the role Islam plays in the perpetuation of disenfranchisement in the suburbs, where Muslims are over-represented.

Some in France have sought to blame Islam for the high levels of unemployment, underachievement, violence and marginalisation in France’s ghettoised suburbs, while others have protested the Islamification of the discourse on the suburbs, decrying the use of confused and loaded terminology to overlook substantial economic and social problems in these areas. In France, with or without the caricatures, Islam is a sore topic with many recent polemics related to Islamic practises, whether the face veil debate, street prayers or the building of new mosques.

French Muslims are regularly told — even by the President — that you either “love France or you leave her”, reinforcing their status as outsiders, and a right-wing discourse which promotes ridiculous predictions of a Muslim take over of Europe through high birth rates and proselytising, is gaining ground. Christopher Caldwell, a contributor to the Financial Times recently published an inflammatory book Reflections on the Revolution In Europe: Immigration, Islam, and the West which has gained widespread media coverage, including on mainstream French TV, with its thesis that Europe is doomed in the face of a Islamic cultural invasion. In this context, marked by fear of Islam’s alleged resurgence, intractability and incompatibility with “French culture”, as well as the inability of many French Muslims to present an alternative perspective on an equal platform, are the seeds of profound social malaise.

Satire of religion has a long history in France and Christians are not exempt from what some groups have deemed insensitive and injurious portrayals of sacred persons or ideas. Since its launch on 20 October, Christian groups have regularly interrupted the Paris based theatrical production of “On the concept of the face of the son of God” (Sur le concept du visage du fils de Dieu) for its perceived blasphemy and “Christianophobia”.

The play features an elderly man defecating on stage and his son coming to clean his back side, using the portrait of Jesus. The excrement collected is then used at the end of the play by children as missiles to be thrown at the portrait of Christ, whilst at the end of the production, a black veil of excrement glides down the portrait of Jesus. In April this year, an art exhibit entitled Piss Christ, featuring a crucifix immersed in a glass containing blood and urine was vandalised by Christians outraged by the piece. Some religious groups have accused the arts and the media to resorting to crass provocations to raise the profile of otherwise mediocre artistic endeavours which might not have garnered public attention without the controversy.

Charlie Hebdo’s current confrontation with Islamic polemics is not its first. In 2008, it won a legal case against accusations of incitement to racial hatred when it chose to reprint the Danish cartoons, launched by the French Muslim Council (CFCM) and the Grand Mosque of Paris. Interviewed on recent events, Mohammed Moussaoui, president of the CFCM has both condemned the attack on Charlie Hebdo and the printing of the irreverent images.

Describing the decision to print images known to be offensive to Muslims as “hurtful” and questioning the association of the caricatures of Prophet Mohamed with events in Tunisia or Libya, he defended the right of those who opposed the decision to protest as well as the freedom of the press to print the said images and explained that in a plural society, people’s relationship to the sacred will necessarily vary.

The attack on the press outlet, Charlie Hebdo is symptomatic of the broader unease French society is facing in light of a growing visible Muslim minority. While successive generations of “French” origin are getting more secular in their outlook, with around 60 per cent of youths saying in 2008 that they had no religious belief, the pattern among the children of immigrants from north Africa, Sahel and Turkey is the opposite, as religion gains in importance, particularly among the young.

How France negotiates an inclusive public sphere in which the views of all its citizens, including those who abide by a religious tradition, are reflected remains a stark challenge. It is telling that Charlie Hebdo chose Mohammed as “guest editor”, rather than a contemporary figure who could express an accurate reflection of French Muslim opinion on current affairs — instead, it chose the route of ease, ascribing archaic and reactionary ideas to a sacred figure, his ideas rigidified and frozen in a literalist caricature, which although undoubtedly humorous in parts, is completely out of sync with how most Muslims understand Islam’s relationship to the modern context. This issue might be its best-selling; the real question though ought to be, is it its best?

Myram Francois-Cerrah is a writer, journalist and budding academic

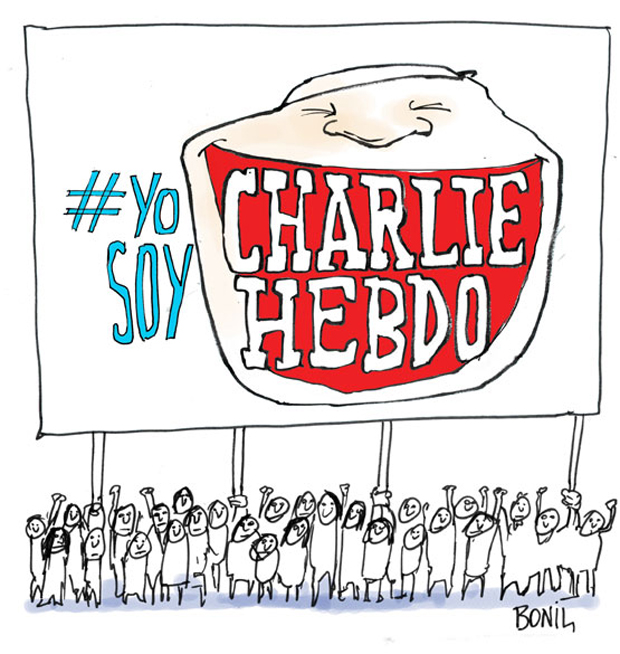

On World Press Freedom Day, 116 days after the attack at the office of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo that left 11 dead and 12 wounded, we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to defending the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that we and others may find difficult, or even offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack – a horrific reminder of the violence many journalists around the world face daily in the course of their work – provoked a series of worrying reactions across the globe.

In January, the office of the German daily Hamburger Morgenpost was firebombed following the paper’s publishing of several Charlie Hebdo images. In Turkey, journalists reported receiving death threats following their re-publishing of images taken from Charlie Hebdo. In February, a gunman apparently inspired by the attack in Paris, opened fire at a free expression event in Copenhagen; his target was a controversial Swedish cartoonist who had depicted the prophet Muhammad in his drawings.

A Turkish court blocked web pages that had carried images of Charlie Hebdo’s front cover; Russia’s communications watchdog warned six media outlets that publishing religious-themed cartoons “could be viewed as a violation of the laws on mass media and extremism”; Egypt’s president Abdel Fatah al-Sisi empowered the prime minister to ban any foreign publication deemed offensive to religion; the editor of the Kenyan newspaper The Star was summoned by the government’s media council, asked to explain his “unprofessional conduct” in publishing images of Charlie Hebdo, and his newspaper had to issue a public apology; Senegal banned Charlie Hebdo and other publications that re-printed its images; in India, Mumbai police used laws covering threats to public order and offensive content to block access to websites carrying Charlie Hebdo images. This list is far from exhaustive.

Perhaps the most long-reaching threats to freedom of expression have come from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries, including France, Britain and Germany, issued a statement in which they called on internet service providers to identify and remove online content “that aims to incite hatred and terror”. In the UK, despite the already gross intrusion of the British intelligence services into private data, Prime Minister David Cameron suggested that the country should go a step further and ban internet services that did not give the government the ability to monitor all encrypted chats and calls.

Index report: Europe’s journalists face growing climate of fear

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the state. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On World Press Freedom Day, we, the undersigned, call on all governments to:

• Uphold their international obligations to protect the rights of freedom of expression and information for all, especially journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders to publish, write and speak freely;

• Promote a safe and enabling environment for those who exercise their right to freedom of expression, especially for journalists, artists and human rights defenders to perform their work without interference;

• Combat impunity for threats and violations aimed at journalists and others threatened for exercising their right to freedom of expression and ensure impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations that bring masterminds behind attacks on journalists to justice, and ensure victims and their families have speedy access to appropriate remedies;

• Repeal legislation which restricts the right to legitimate freedom of expression, especially such as vague and overbroad national security, sedition, blasphemy and criminal defamation laws and other legislation used to imprison, harass and silence journalists and others exercising free expression;

• Promote voluntary self-regulation mechanisms, completely independent of governments, for print media;

• Ensure that the respect of human rights is at the heart of communication surveillance policy. Laws and legal standards governing communication surveillance must therefore be updated, strengthened and brought under legislative and judicial control. Any interference can only be justified if it is clearly defined by law, pursues a legitimate aim and is strictly necessary to the aim pursued.

PEN International

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

Albanian Media Institute

Article19

Association of European Journalists

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian PEN

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Centre for Independent Journalism – Malaysia

Danish PEN

Derechos Digitales

Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

English PEN

Ethical Journalism Initiative

Finnish PEN

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Guardian News Media Limited

Icelandic PEN

Index on Censorship

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

International Federation of Journalists

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Malawi PEN

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Institute of Southern Africa

Media Rights Agenda

Media Watch

Mexico PEN

Norwegian PEN

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

PEN Afrikaans

PEN American Center

PEN Catalan

PEN Lithuania

PEN Quebec

Russian PEN

San Miguel Allende PEN

PEN South Africa

Southeast Asian Press Alliance

Swedish PEN

Turkish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

West African Journalists Association

World Press Freedom Committee

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

The decision by six authors to withdraw from a PEN American Center gala in which Charlie Hebdo will be honoured with an award once again emphasises the dangerous notion that some forms of free expression are more worthy than others of defending.

Charlie Hebdo was offensive to many — but as PEN points out — it was also vigorous in its defence of the importance of free speech, even in the face of those who would seek to silence that view through violence.

“Free speech for all can only be protected by standing up as vigorously – if not more vigorously – for the views you disagree with as those with which you agree,” said Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “If we don’t do that, freedom becomes something only for the favoured and powerful.”

Below Index republishes an article from CEO Jodie Ginsberg written a week after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo that addresses the importance of a defence of free speech in all its forms.

If you said “I believe in free expression, but…” at any point in the past week, then this is for you. If you declared yourself to be “Charlie”, but have ever called for an offensive image to be removed from public viewing, then this is for you. If you “liked” a post this week affirming the importance of free speech, but have ever signed a petition calling for a speaker to be banned, then this is for you.

Because the rush to affirm our belief in free expression in the wake of Charlie Hebdo attacks ignores a simple truth: that free speech is being eroded on all sides, and all sides are responsible. And it needs to stop.

Genuine free expression means being able to articulate thoughts, feelings and ideas without fear of harm. It is vital because without it individuals would be subject to the whim of whichever authority dictated what ideas and opinions – as opposed to actions – are acceptable. And that is always subjective. You need only look at the world leaders at Sunday’s Paris solidarity march to understand that. Attendees included Ali Bongo, President of Gabon, where the government restricts any journalism critical of the authorities; Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, whose country imprisons more journalists in the world than any other; and the UK’s David Cameron, who declared his support for free expression and the right to offend, while his government considers laws that could drive debate about extremism underground.

It is precisely the freedom for others to say what you may find offensive that protects your own right to express your views: to declare, say, your belief in a God whom others deny exists; or to support a political system that others dismiss. It is what enables scientific and academic thought to progess. As soon as we put qualifications around “acceptable” free expression, we erode its value. Yet that is precisely what happened time and again in response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks, with individuals simultaneously declaring their support for free expression while seeming to suggest that the cartoonists and anyone else who deliberately courts offence should choose other ways to express themselves – suggesting that the responsibility for “better” speech always lies with the person deemed to be causing offence rather than the offended.

“The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write and print with freedom…”

French National Assembly, Declaration of the Rights of Man, August 26, 1789

Index believes that the best way to tackle speech with which you disagree, including the offensive, and the hateful, is through more speech, not less. It is not through laws and petitions that restrict the rights of others to speak. Yet, increasingly, we use our own free speech to call for that of others to be limited: for a misogynist UK comedian to be banned from our screens, or for a UK TV personality to be prosecuted by police for tweeting offensive jokes about ebola, or for a former secretary of state to be prevented from giving an address.

A project mapping media freedom in Europe, launched by Index just over six months ago, shows how journalists are increasingly targeted in this region, including – prior to last week’s incidents – 61 violent attacks against the media. Globally, the space for free expression is shrinking. We need to reverse this trend.

If you genuinely believe in the value of free speech – that all ideas and opinions must be heard – then that necessarily extends to the offensive and the vile. You don’t have to agree with someone, or condone what they are saying, or the manner in which it is said, but you do need to allow them to say it. The American Civil Liberties Union got this right in 1978 when they defended the rights of a pro-Nazi group to march in Chicago, arguing that rights to free expression needed apply to all if they were to apply to any. (As did charity EXIT-Germany late last year, when it raised money for an anti-fascism cause by donating money for every metre walked during a neo-Nazi march).

Countering offensive speech is – of course – only possible if you have the means to do so. Many have observed, rightly, that marginalisation and exclusion from mainstream media denies many people the voice that we would so vociferously defend for a free press. That is a valid argument. But this should be addressed – and must be addressed – by tackling this lack of access, not by shutting down the speech of those deemed to wield power and privilege.

Voltaire has been quoted endlessly in support of free expression, and the right to agree to disagree, but British author Neil Gaiman, who discusses satire and offence in the winter Index magazine, also had it right. “If you accept — and I do — that freedom of speech is important,” he once wrote, “then you are going to have to defend the indefensible. That means you are going to be defending the right of people to read, or to write, or to say, what you don’t say or like or want said…. Because if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

This article was originally posted on 12 January 2015 and reposted on 27 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

When drawings being scribbled,

colours dripping red,

words being silenced,

thoughts being limited,

lives turn to nothing,

can you touch pain with politics?

Can you perceive pain with your beliefs?

Lives smeared with blood,

your loved ones lying on the ground

lifeless…

Can you hold on to reason,

and when fear like dark clouds

leaks within everyone,

and when fear feeds more fears

and when fear swells hatred

with its giant steps,

can you cure desperation with laws?

When walls are being built again

for the sake of freedom and security,

with violence and blood,

can you create peace with concepts,

when a person without blinking an eye

can kill another person,

when another can glorify death

for the sake of religion?

The moment you declare

you believe,

if the world stops turning,

if reasoning,

sensibility,

sensitivity,

goes blind against beliefs

and even a pen could be perceived as a weapon,

how can thoughts be free?

What would expressing yourself mean?

This poem was posted on 14 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org