12 Feb 2018 | Global Journalist, Media Freedom, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published interviews with exiled journalists from around the world.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”97954″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]In hindsight, there were many clues that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government was making preparations to eliminate Turkey’s independent media even before it launched a massive crackdown in July 2016. But perhaps the biggest tip-off was the March 2016 police raid and seizure of Zaman, Turkey’s largest daily newspaper.

At the time, Abdullah Bozkurt was bureau chief in the capital Ankara for the paper’s English-language edition, Today’s Zaman. On March 4 of that year, Bozkurt found himself struggling to put out the newspaper’s final edition – even as he watched on live television as police in riot gear fired tear gas and water cannons on protesters and stormed Zaman’s headquarters 220 miles (350 km) to the west in Istanbul.

Shortly before court-appointed trustees seized control of the newspaper’s computer system, Bozkurt wrote the headline for the last cover of Today’s Zaman. “Shameful Day for Free Press in Turkey,” it read. “Zaman Media Group Seized.”

Zaman had been in Erdogan’s crosshairs for some time for its sympathies with the Gülen movement, an opposition group affiliated with a U.S.-based Islamic cleric that Erdogan has branded a “terrorist” organization. It had particularly angered the government for its aggressive coverage of a 2013 corruption investigation that led to the arrests of three sons of ministers in then-prime minister Erdogan’s government, Bozkurt says.

“Initially, they started calling in public rallies [for people] not to purchase our newspaper,” says Bozkurt, in an interview with Global Journalist. “Amazingly, at the time our circulation went up because we were one of the few media outlets in Turkey that were still covering the corruption investigation…later they started putting pressure on advertisers. That didn’t work out either because our circulation was quite high.”

After Zaman’s closure, Bozkurt briefly opened his own news agency. A few weeks later, on July 15, 2016, a faction of the military attempted to overthrow Erdogan. The coup was put down in a matter of hours. But in its aftermath, Erdogan unleashed a nationwide purge.

Over 100,000 government workers were fired and 47,000 people were jailed on suspicion of terrorism, according to a tally by Human Rights Watch. An additional 150 journalists and media workers were also jailed, giving Turkey the highest number of jailed journalists in the world. Many others fled the country.

Bozkurt was among those who chose to flee rather than face arrest. Ten days after the failed coup, he left for Sweden. The day after he left, the offices of his fledgling news agency were raided by police. Police later searched the home of Bozkurt’s 79-year-old mother and detained her for a day. Bozkurt’s wife and three children later followed him.

In Sweden, Bozkurt received threats via social media and a Wild West-style ‘wanted photo’ of him was published by pro-Erdogan newspapers and the state-run news agency. The government has brought anti-state charges against 30 of his former Zaman colleagues, seeking as much as three life sentences in jail.

Bozkurt, 47, now writes regular columns for the news site Turkishminute.com and works at the Stockholm Center for Freedom, a rights group focused on Turkey. He spoke with Global Journalist’s Denitsa Tsekova about his last weeks in Turkey and his exile. Below, an edited version of their interview:

Bozkurt: I was based in the capital, Ankara, but our newspaper’s headquarters was in Istanbul. The storming of our newspaper happened in Istanbul, we were watching on TV. We were on the phone talking to our colleagues in Istanbul, trying to find what’s going on, what we can do. The police were coming into our Istanbul’s newsrooms, ransacking the place, and shutting the internet service. It was up to me and my colleagues in the Ankara office to write the stories. We were actually printing the last edition of Zaman from Ankara. I was the one who drew the headline in the English edition and we managed to get out the last free edition. In the Turkish edition, we managed to finish and print the first one, but the second and the third edition couldn’t make it to the printing place. It was interrupted by the police and the government caretakers who took over the company.

GJ: There were protests after the closure of Zaman. What happened?

Bozkurt: It was on the day when the takeover judgment by the court was publicized. We didn’t call our readers to come and protest.

We knew it might be very dangerous because the government uses very harsh measures often rubber bullets, pepper spray and pressurized water against peaceful protesters. We didn’t want to put them on the risk.

Around 400 people showed up and they were beaten and targeted brutally by the police who stormed the building.

GJ: What was the last article you wrote for Today’s Zaman?

Bozkurt: It was about prisons. When I wrote that article I didn’t know the government was taking over the company, it was written a day before.

I talked to many people in the government and some from the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture. Something was very, very off because the government planned to build a lot of prisons in Turkey under the disguise of a modernization plan.

However, when you look at the numbers, it didn’t really match. We didn’t need that many new prisons in Turkey, but the government was making a projection that the prison population would increase.

When the European officials asked the justice ministry on what basis were they making this projection, they did not have a response.

In hindsight, I could understand it was because they were preparing a new mass prosecution in Turkey and they needed more prisons to put these people away. Even the prisons we have now are not enough; people are living in very crowded cells. After the coup, the government even granted amnesty for some 40,000 convicted felons… just to make space for the political prisoners and journalists.

GJ: How did you decide to leave?

Bozkurt: I actually hung around for a while after the failed coup, because I thought eventually things will settle down, and I wasn’t planning to move out of Turkey at all.

[Ten days] after the coup, the government issued an arrest warrant against 42 journalists on a single day. I realized this is going to get worse, and I said it’s time for me to move out of Turkey.

It was a rash decision, I didn’t even know to which country I would go, so I had to go to Germany first and then to Sweden.

My mother was getting old, she has some health issues and I wanted to be there for her. But it wasn’t up to me. Sweden was a stopover for me, I wasn’t planning on staying permanently.

The day after I left Turkey, the police raided my office in Ankara, so it was the right decision. If I was there I would have been detained and dragged to jail.

GJ: Were you getting threats?

Bozkurt: I was getting threats all the time. If you are a critical and independent journalist, you will get them. That’s the price you pay for it. Sometimes you try to be vigilant, you try to be careful and you just ignore that kind of threats or pressure from the government or pro-government circles.

But after the massive crackdown after the coup attempt, I thought it’s no longer safe for me. I moved out alone, I didn’t even take my family, because I thought they will stay in Turkey and I can hang around abroad and then come back to Turkey. That was my plan.

After a while, the Turkish government started going after the family members of the journalists. Bülent Korucu was a chief editor of a national daily [Yarına Bakıs], which was also shut down by the government, and he was facing an arrest warrant. The police couldn’t find him and they arrested his wife, Hacer Korucu. She stayed in prison for a month on account of her husband. At that moment, I thought my family is no longer safe either, so I decided to extract them out of the country.

GJ: Was your family directly threatened?

Bozkurt: When I moved out of Turkey I kept writing about what’s going on in Turkey. I guess they felt uncomfortable with my writings.

It was part of the intimidation campaign to go after family members, including my mother. She is a 79-year-old, she lives alone but sometimes my sister helps her out. Police raided her home in my hometown of Bandirma in December 2016, searched the house and placed her in detention for a day. She was questioned about me.

Why does she deserve that? They want me to shut up, to be silent even though I feel safe abroad.

GJ: What will happen if you go back to Turkey?

Bozkurt: Of course I will get arrested. They even posted a “wanted” picture of me, and it was run in the pro-government dailies and in the state news agency. It’s like in the old Western movies: there is a picture of me and where I live. I have no prediction when I can go back to Turkey. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/tOxGaGKy6fo”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”6″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”2″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1517591299623-14a913d2-eca2-3″ taxonomies=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Nov 2016 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Letters

A coalition of 14 leading international press freedom and freedom of expression organisations today condemned as an “extraordinary attack on press freedom” the jailing of top journalists with Turkey’s Cumhuriyet newspaper and the closure of 15 pro-Kurdish media in a letter to leading Turkish officials.

On Monday, October 31, Turkish authorities launched a mass operation against Cumhuriyet, a secular daily considered one of the last opposition media voices in Turkey. Police arrested nearly a dozen journalists, managers and lawyers, including Editor-in-Chief Murat Sabuncu and columnist Kadri Gürsel, a member of the International Press Institute’s global Executive Board.

The coalition said today it was “deeply disturbed” by the attack both against “a highly respected newspaper that remains one of Turkey’s last sources of critical news and information and a representative of a major international human rights organisation”.

The operation against Cumhuriyet followed the closure of 15 pro-Kurdish media outlets on Saturday, which the coalition described as a “further attempt by the Turkish government to control all media coverage of the ongoing operations [in the country’s South East], and prevent independent media from investigating grave human rights abuses there”.

Members of the coalition called on Turkey to immediately release the detained Cumhuriyet journalists, as well as the estimated more than 130 other journalists currently behind bars “for exercising their right to freedom of expression” in the country.

In copies of the letter addressed to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım, Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu and Justice Minister Bekir Bozdag, the group made an urgent request to discuss its concerns in person.

Read the text of the letters below in English and Turkish. The letter can also be downloaded as a PDF in English and Turkish.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Cumhurbaşkanlığı Külliyesi 06560 Beştepe-Ankara

Sent via email

02 November 2016

Dear President Erdoğan:

The undersigned members of an international coalition of leading press freedom and freedom of expression groups request an urgent meeting with you following Monday’s operation against the newspaper Cumhuriyet and Saturday’s closure of 15 pro-Kurdish media outlets.

Police on Monday arrested and raided the homes of at least a dozen journalists working for Cumhuriyet. Among those arrested were Editor-in-Chief Murat Sabuncu and columnist Kadri Gürsel. Mr. Gürsel is also a member of the Executive Board of the International Press Institute (IPI) and IPI’s official representative in Turkey.

We are deeply disturbed by this move against not only a highly respected newspaper that remains one of Turkey’s last sources of critical news and information but also a representative of a major international human rights organisation.We are also extremely concerned that those detained are being held without access to legal counsel and without a clear indictment against them.

The closure of 15 pro-Kurdish media outlets, primarily covering the South East of the country, is part of an ongoing campaign to censor the Kurdish minority. It also represents a further attempt by the Turkish government to control all media coverage of the ongoing anti-terror operations in this region, and prevent independent media from investigating grave human rights abuses occurring there.

We condemn these arrests and closures as an extraordinary attack on press freedom, freedom of expression and the journalistic profession – unfortunately merely the latest example of such in Turkey. Our organisations stand in solidarity with Mr. Sabuncu, Mr. Gürsel and their colleagues, as do journalists around the world.

Prosecutors have said that Mr. Sabuncu, Mr. Gürsel and their colleagues are suspected of criminal collaboration with the outlawed Gülenist movement and the PKK. While we understand the need to take appropriate action against those responsible for July’s failed coup attempt, the arrests of Cumhuriyet staff and the sweeping closures of Kurdish media make it clear that Turkey’s current state of emergency is being abused to indiscriminately target any and all who criticise the government.

Indeed, during the first three months of the state of emergency, the Turkish authorities have closed approximately 165 media outlets. Nearly 100 journalists and writers have been arrested and at least 140 journalists are currently in detention, many of whom have no connection to either the Gülenist movement or the PKK.

We would welcome the opportunity to bring our concerns to you directly.

In the meantime, this coalition calls for the immediate release of Murat Sabuncu, Kadri Gürsel, their colleagues at Cumhuriyet and all other journalists jailed for exercising their right to freedom of expression. We also call on lawmakers in Turkey to end the abuse of emergency powers that are being used to suppress legitimate dissent, further crackdown on independent media and undermine what is left of the rule of law.

Thank you for your attention to this urgent matter.

The International Press Institute (IPI)

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Article 19

Index on Censorship

The Ethical Journalism Network (EJN)

PEN International

The World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA)

The South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

IFEX

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

CC: Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım

Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu

Justice Minister Bekir Bozdag

Foreign embassies and consulates in Ankara and Istanbul

Sayın Cumhurbaşkanı,

Dünyanın önde gelen basın ve ifade özgürlüğü örgütlerinden oluşan uluslararası koalisyonun altta imzası bulunan üyeleri olarak, Cumhuriyet Gazetesi’ne yapılan operasyonun ve Kürtlere yönelik yayınlarıyla bilinen 15 medya kuruluşunun kapatılmasının ardından, acil toplantı talebimizi iletmek üzere bu mektubu yazıyoruz.

Polis, Cumhuriyet Gazetesi’nde çalışan en az bir düzine gazeteciyi, pazartesi günü evlerine baskın düzenleyerek gözaltına almıştır. Gözaltına alınanlar arasında, IPI’ın Yönetim Kurulu Üyesi ve Türkiye’deki resmi temsilcisi Sayın Kadri Gürsel ile IPI üyesi olan Cumhuriyet Genel Yayın Yönetmeni Murat Sabuncu da vardır.

Türkiye’de eleştirel haber ve yorumların yer alabildiği az sayıda kaynaktan biri olan Cumhuriyet’e yönelmekle birlikte, aynı zamanda önde gelen bir uluslararası insan hakları örgütünün temsilcisini de hedef alan bu hamle, bizde derin bir rahatsızlık yaratmıştır.

Özellikle de ülkenin güneydoğusundan haberler veren 15 medya kuruluşunun kapatılması, Kürt azınlığın sansürlenmesi için sürdürülen kampanyanın bir parçasıdır. Bu karar, Türk hükümetinin, bölgede süren terörle mücadele operasyonlarının haberleştirilmesinde tüm medyayı kontrol altına almak yönündeki çabasında yeni bir adımı temsil ediyor.

Bu gözaltı ve kapatma kararlarını, basın ve ifade özgürlüğü ile gazetecilik mesleğine yönelik olağanüstü bir taarruz olarak görüp kınıyoruz –ki bu durum ne yazık ki Türkiye için bir ilk değildir. Dünyanın dört bir yanındaki gazetecileri temsil eden örgütlerimiz, Sayın Gürsel, Sayın Sabuncu ve diğer meslektaşlarımızın yanındadır.

Savcılar, Sayın Gürsel ve Sabuncu’nun yasadışı örgütler olan Gülen hareketi ve PKK ile suç teşkil eden bir işbirliğinde olduğundan şüphelendiklerini söylüyorlar. 15 Temmuz darbe girişiminden sorumlu olanlara karşı uygun bir eylemin yapılması gerektiğine inanmakla birlikte, Cumhuriyet çalışanlarına yönelik gözaltılarla Kürtlere yönelik yayın yapan medya kuruluşlarının kapatılmasının bu kapsama girdiğini düşünmüyoruz. Bu gözaltılar, daha ziyade, Türkiye’deki mevcut OHAL yönetiminin, hükümeti eleştirmeye cüret eden herkese karşı ayrım gözetmeksizin kullanıldığını gösteriyor.

Gerçekten de, OHAL’in ilk üç ayı içinde Türk yetkililer yaklaşık 165 medya kuruluşunu kapatmış, 100 kadar gazeteci ve yazarı tutuklamış, birçoğu Gülen hareketi veya PKK ile hiçbir bağlantısı olmadığı halde en az 140 gazeteciyi gözaltına almıştır.

Endişelerimizi zât-ı âlilerinize doğrudan iletme fırsatını bulursak çok memnun oluruz.

Bu arada, uluslararası basın özgürlüğü koalisyonu olarak Sayın Gürsel, Sayın Sabuncu ve Cumhuriyet’teki diğer meslektaşlarımızla, ifade özgürlüğü hakkını kullandıkları için hapsedilen tüm gazetecilerin derhal salıverilmesi yönünde çağrı yapıyoruz. Türkiye’deki kanun yapıcıları, OHAL yetkilerini meşru muhalefeti susturmaya, özgür medyaya daha fazla baskı yapmaya ve tüm bunlardan arda kaldığı kadarıyla hukuk devletinin altını oymaya son vermeye davet ediyoruz.

Bu acil konudaki dikkatiniz için teşekkür ederiz.

Saygılarımızla,

The International Press Institute (IPI)

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Article 19

Index on Censorship

The Ethical Journalism Network (EJN)

PEN International

The World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA)

The South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

IFEX

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

The European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

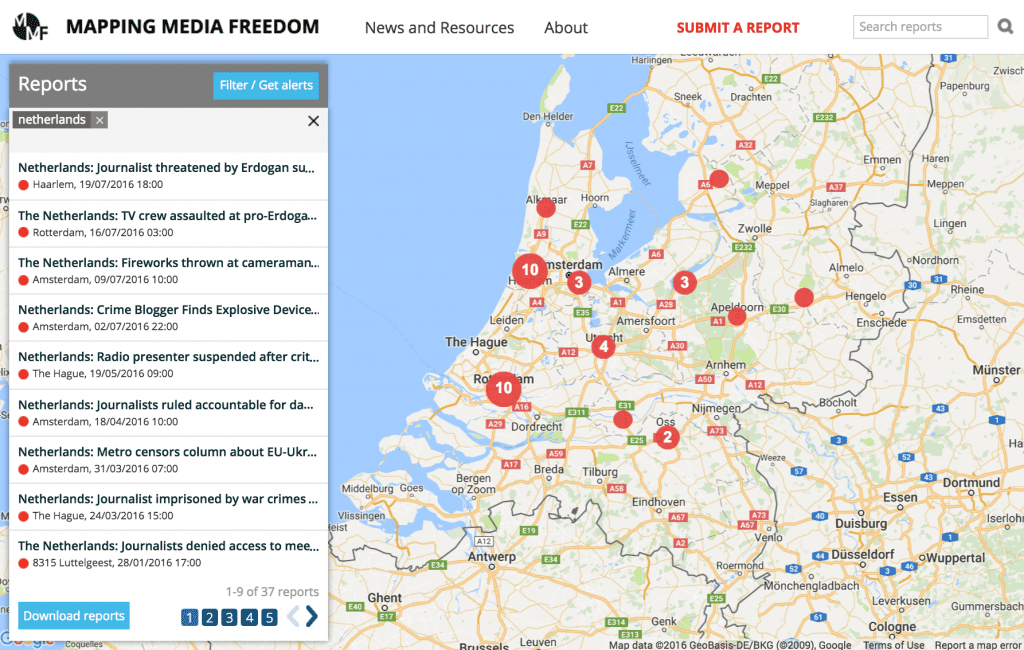

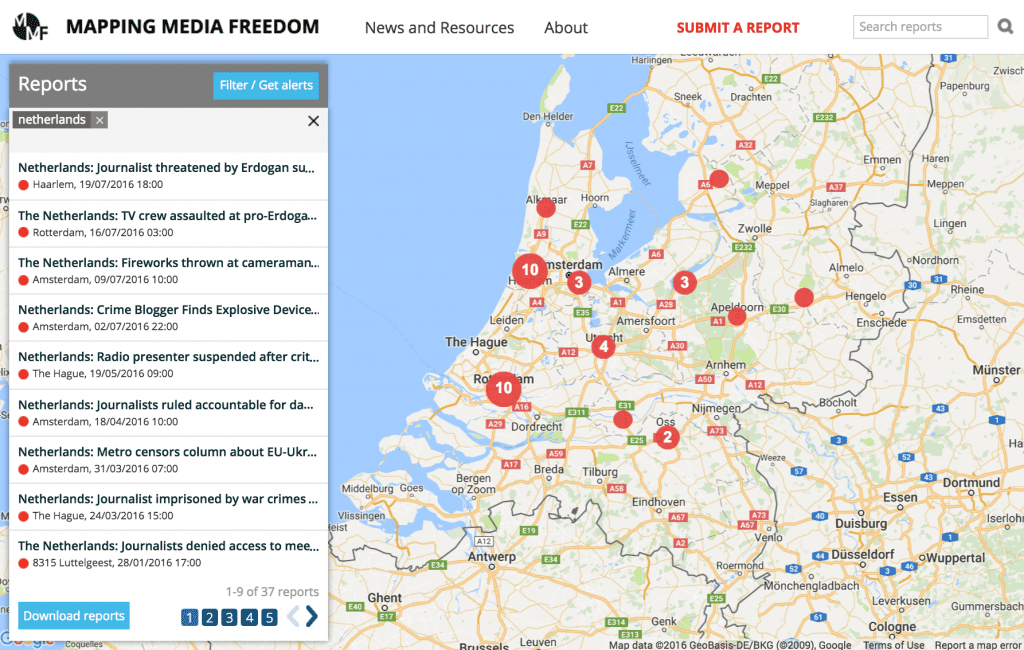

3 Aug 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Netherlands, News and features, Turkey

Following last month’s failed coup, journalists in Turkey are facing the largest clampdown in its modern history. Journalists covering the events from abroad have not escaped unscathed, including a number in the Netherlands who have faced threats and attacks.

Unusually, the journalists of the Rotterdam-based Turkish newspaper Zaman Today welcomed the increased police presence. Long before the military coup that failed to remove Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan from power, the government had been targeting journalists. But today a Dutch police officer drops by frequently to check if Zaman’s journalists are alright. It makes journalist Huseyin Atasever, who has been working for the Dutch Zaman since 2014, feel safe. Or at least safer than he has felt in a while.

On the morning of Tuesday 19 July Atasever was on his way to Amsterdam when he received a phone call. A Turkish-Dutch individual had been abused by Erdogan supporters at a mosque in the city of Haarlem. Atasever decided to go there immediately.

“I found a man sitting in a corner on the floor talking to the police,” he told Index on Censorship. “He was injured and his clothes were torn.”

After Atesaver had interviewed the victim, who had been targeted for being critical of Erdogan, he approached a group of Erdogan supporters nearby to hear their side of the story.

“When these men realised that I work for Zaman Today, things got grim,” Atasever said. “A few of them surrounded me and started shouting death threats at me. They told me ‘we will kill you, you are dead’.”

“Thanks to immediate police intervention I managed to get away unhurt,” he added.

More than ever before, Turks all over the world have seen their diaspora communities divided between supporters and critics of Erdogan.

At around half a million people, the Netherlands has one of the largest Turkish communities in Europe. In the days after the coup, thousands of Dutch Turks took to the streets in several cities to show their support for the Turkish president. Turks critical of the Erdogan government had told media that they’re afraid to express their opinions due to rising tensions.

People suspected of being supporters of the opposition Gulen movement, led by Erdogan’s US-based opponent and preacher Fethullah Gulen, which has been accused of being behind the coup attempt, have been threatened and physically assaulted in the streets. The mayor of Rotterdam, a city with a large Turkish community, urged Dutch-Turks to remain calm and ordered increased police protection of Gulen-aligned Turkish institutions.

The men who had threatened Atasever were arrested, but released shortly afterwards. Atasever said he has pressed charges against them. He still receives threats on social media every day: he has been called a traitor, a terrorist and a coup supporter on Twitter. His photo and contact details have been shared on several social network sites accompanied by messages like “he should be hanged” and “let’s go find him”.

On 1 August Zaman Today’s Dutch website was hit by a DDoS attack and knocked offline for about an hour. An Erdogan supporter reportedly had announced an attack on the website earlier via Facebook, and Zaman Today announced it will be pressing charges.

It hasn’t just been journalists of Turkish descent who have been attacked. During a pro-Erdogan demonstration at the Turkish Consulate in Rotterdam, a TV crew for the Dutch national broadcaster NOS was verbally harassed by a group of youth. NOS reporter Robert Bas told the network that his cameraman had been assaulted and their car was also damaged. “There’s a very strong anti-western media atmosphere here,” Bas said in a live TV interview at the scene.

The Dutch Union for Journalists (NVJ) is worried about growing intimidation of journalists in the Netherlands, NVJ chairman Rene Roodheuvel said in Dutch daily Trouw. “The political tensions at the moment in Turkey and the attitude towards journalists there may in no circumstance be imported into the Netherlands,” he said. “We are second in the world when it comes to press freedom. Media freedom is a great good in the Dutch democracy and it must always be respected.”

“AKP supporters believe that media, especially in the west, are part of an international conspiracy to overthrow Erdogan,” Atasever said. Being a journalist for Zaman Today, he is not new to receiving threats. Many Turks feel the Western media is “the enemy”, he explained. “But we are even worse because we are of Turkish descent. They see us as traitors of our country.”

The government took control of the Turkish edition of Zaman in March 2016. Zaman was a widely distributed opposition newspaper, and very critical of the Erdogan government. The paper had ties with Gulen, who has denied any involvement in the coup attempt, but the Turkish government accuses him a running a parallel government. Zaman and its English-language edition, Today’s Zaman, have since been turned into a pro-government mouthpiece.

Most of Zaman’s foreign editions, however, have so far avoided government control. Zaman has editions in different languages around the world. The Dutch edition, Zaman Vandaag, with a circulation of 5,000, has managed to keep its editorial independence.

While independent journalists in Turkey are being arrested one by one, journalists of Turkish descent in the Netherlands are starting to worry too. “I know for a fact that our names have been given to the Turkish government by Dutch AKP supporters, labelling us as traitors and enemies of the state,” said Atasever, who has no plans to travel to Turkey.

“If our names are on a wanted list, which I expect they are, we will be arrested as soon as we set foot in Turkey.”

1 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkish journalist Lale Kemal

It was a long Saturday night for all of us, at home and abroad, monitoring the worrisome developments around media freedom in Turkey. As if to confirm our fears, the night ended with the detention of six more journalists.

Defence lawyers expected the cases to be handled first thing Monday 1 August. But in a hasty move, journalists who wrote for the opinion section of Zaman — which stands at the epicentre of accusations of being part of the so-called “media leg of FETO terror organisation” — were taken to the Istanbul courthouse. After a long process, all were sent to jail.

The ruling, written under the extraordinary circumstances of emergency rule, reads like a severe restriction of the free word in particular and journalism in general.

The motivation for detention went, in a nutshell, that the six “prevented the investigation on the armed structure in their columns and via social media, and continued to write their columns even after the chief editor of Zaman daily, Ekrem Dumanlı, had fled the country”. Sigh.

There was no other mention than their expressed views — without going into any specifics in their content — and it was seen as sufficient by the judge to rule for jailing. Theirs will add to the pile of complaints from Turkey at the European Court of Human Rights.

It was the case of Şahin Alpay in particular which raised concerns among his colleagues in media and academia. One of the top liberal voices in Turkey, and known with respect among others in German social democrat, liberal and green political circles, Alpay is utterly frail with several health issues. The hopes of a release — albeit conditional — were high but crashed.

Yesterday, his family tried to contact him in prison, uncertain of any success.

All the six are from Turkish media’s liberal end of the spectrum. Among them are two female reporters that require attention. Lale Kemal, who was a commentator with Zaman, is an expert journalist on defence issues, with a long career. Her CV begins with Anatolian Agency, going on with Cumhuriyet daily, Hürriyet Daily News, Taraf and Today’s Zaman. She has been a stringer for Jane’s Defence Weekly for a long time.

The other, Nuriye Akman, has been a professional for 25 years. She worked with “mainstream” dailies in the 1990s and marked her reputation with long, Oriana Fallaci-style interviews both in print and TV. She is also the author of three novels.

Both women have been known to earn their keep only through journalism, like the others in this group of detainees.

Ali Bulaç, with a background as a theologue, is an independent voice within the conservative segments, often with disagreements and polemics with some others in the group. Ahmet Turan Alkan is regarded as a senior voice as part of the centre-right liberal flank in Turkey, popular for his ironic style. And Mustafa Ünal, who was Ankara Bureau Chief of Zaman, was for long active in Ankara, covering major political issues with a minimalist, simple writing style.

According to the regular monitoring done in daily basis by Platform for Independent Journalism (P24), these latest detentions mean that since the bloody coup attempt on July 15, 29 journalists are detained. In a total, there are now 62 journalists in jail in Turkey.

During the long, dark hours on Sunday, there was another message that added to the fears. A colleague, Ali Aslan, based in Washington DC, tweeted that the police had detained the wife of a journalist Bülent Korucu, former editor in chief of the weekly news magazine Aksiyon, now under arrest warrant but on the run. The police, Aslan claimed, threatened to keep her locked until her husband surrenders. Korucu’s son also confirmed this claim.

Dark Sunday indeed.

What fuels the concerns is that there is so far no assurance from the government about the respect for media freedom and whether or not the witch hunt will end anytime soon.

A version of this article originally appeared at Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.