27 Feb 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Equatorial Guinea, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Caroonist Ramón Esono Ebalé (Photo: CRNI)

Index on Censorship welcomes the news that charges against cartoonist Nsé Ramón Esono Ebalé, who frequently uses his art to lampoon senior Equatorial Guinea government officials, have been dropped.

“This is wonderful news and we urge the authorities in Equatorial Guinea to release Ramon without delay. The charges against him were clearly spurious and we call on the government of Equatorial Guinea to confirm that Ramon will be free to travel,” said Joy Hyvarinen, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship said.

Esono Ebalé, who had been living abroad since 2010, has been held in prison in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea’s capital, since his arrest on September 16, 2017. He was arrested while he was in the country to request a new passport.

Three days after Esono Ebalé’s arrest, the state-owned TV channel ran a report alleging that he had been arrested for counterfeiting and attempting to launder approximately US$1,800 of local currency found in the car he was driving.

Esono Ebalé was not formally charged until 82 days after his arrest. This prolonged period – during which the investigating judge did not respond to three pleadings or motions submitted by his lawyers – called into question the credibility of the evidence. It also appeared to violate Equatorial Guinean law, which mandates that a judge must charge suspects within 72 hours of arrest, unless the judge recognizes an exception.

The charge sheet alleged that an undercover agent, working on a tip, approached Esono Ebalé to provide change for a large bill and was given counterfeit money in return. The charge sheet also stated that the head of the National Police testified regarding receiving information about Esono Ebalé’s alleged involvement in counterfeiting money and that the false notes were presented to the judge. It included no information as to where the police found the money or other alleged members of the counterfeit ring. The judge refused bail and ordered Esono Ebalé to pay a 20 million CFA francs (US$36,000) assurance to satisfy any fines the court may levy on him.

Cartoonists are frequently targeted by authorities for their work. Malaysian cartoonist Zunar has had his works banned, been barred from international travel and frequently arrested for his work. Indian cartoonist Aseem Trivadi was arrested for sedition in 2012 for a series of cartoons that mocked the government, while Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat lives in exile after being brutally beaten by government forces.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”1″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1519753879317-fe1d51d9-7d5c-0″ taxonomies=”19377″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Nov 2017 | News and features

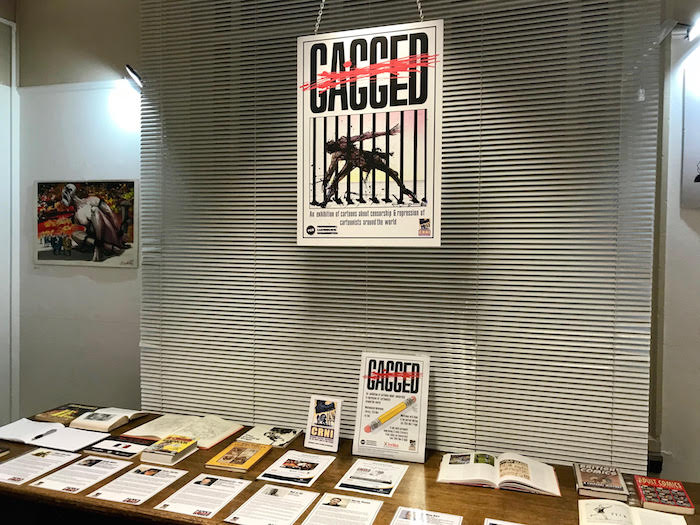

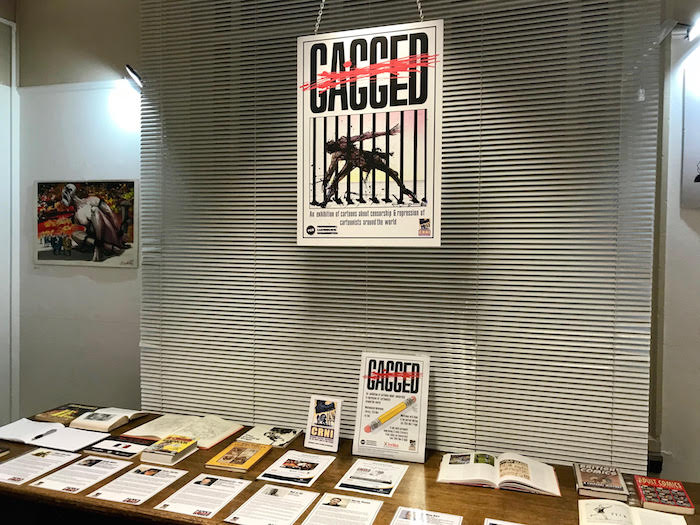

Stall at the Gagged exhibition, showcasing political cartoonists’ work

“This is a key to realms of wonder, but it’s also a deadly weapon, a weapon of mass distraction,” UK cartoonist Martin Rowson said, describing a pen, as he opened a discussion about censorship and repression of political cartoonists.

The event had planned a video link-up with Zulkiflee Anwar Haque, the Malaysian cartoonist better known as Zunar, but he was unable to attend. There have been reports of his arrest. Zunar uses his art to take a stand against corruption in Malaysian politics. The cartoonist is facing 10 sedition charges which are still pending trial. On these charges, Zunar faces 43 years in prison.

In his absence, a video of the cartoonist was shown in which he states, “you can ban my books, you can ban my cartoons, but you cannot ban my mind”.

The Westminster Reference Library hosted a discussion on 28 November, during an exhibition of political cartoons: Gagged. Speakers included Index on Censorship’s Jodie Ginsberg, UK cartoonist Martin Rowson, Sudanese cartoonist Khalid Albaih, and Cartoonist Rights Network International’s Robert Russell.

Cartoonist Rowson and Albaih, currently based in Copenhagen, expressed the responsibility they feel working from a safe environment. They acknowledged the oppression of their colleagues and cited them as inspiration for the cartoons they continue to publish.

“I feel so guilty that I’m here doing this but at the same time, I have a lot of friends who are in jail, who were arrested, and who are really fighting that fight to say what they want to say … It’s something that hurts me everyday”, Albaih said. “Everyday that I’m walking down Copenhagen. It’s a beautiful city but I can’t enjoy it because most of my friends can’t even get a visa to go to the country next to them … People like Zunar, they’re incredible and they’re powerful and I look up to them. And I hope one day I can go back to my country and be able to do that without being scared that something will happen to my kids, you know?”

Ginsberg spoke on the importance of freedom of expression in the face of adversity and the reality of censorship in countries that believe they have “free speech”. “Censorship isn’t something that happens ‘over there’. It happens here and it happens on our doorstep.”

“I genuinely believe that the pen is mightier than the sword, but I also think … that many pens and many voices are even better. Oppressors win when they think their opponents are alone,” Ginsberg said. “We succeed when we demonstrate that it’s not the case.”

**The exhibition has now been extended to 7 December.

22 Nov 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”96621″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Governments have arsenals of weapons to censor information. The worst are well-known: detention, torture, extra-judicial (and sometimes court-sanctioned) killing, surveillance. Though governments also have access to less forceful but still insidious tools, such as website blocking and internet filtering, these aim to cut off the flow of information and advocacy at the source.

Another form of censorship gets limited attention, a kind of quiet repression: the travel ban. It’s the Trump travel ban in reverse, where governments exit rather than entry. They do so not merely to punish the banned but to deny the spread of information about the state of repression and corruption in their home countries.

In recent days I have heard from people around the world subject to such bans. Khadija Ismayilova, a journalist in Azerbaijan who has exposed high-level corruption, has suffered for years under fraudulent legal cases brought against her, including time in prison. The government now forbids her to travel. As she put it last year: “Corrupt officials of Azerbaijan, predators of the press and human rights are still allowed in high-level forums in democracies and able to speak about values, which they destroy in their own – our own country.”

Zunar, a well-known cartoonist who has long pilloried the leaders of Malaysia, has been subject to a travel ban since mid-2016, while also facing sedition charges for the content of his sharply dissenting art. While awaiting his preposterous trial, which could leave him with years in prison, he has missed exhibitions, public forums, high-profile talks. As he told me, the ban directly undermines his ability to network, share ideas, and build financial support.

Ismayilova and Zunar are not alone. India has imposed a travel ban against the coordinator of a civil society coalition in Kashmir because of “anti-India activities” which, the government alleges, are meant to cause youth to resort to violent protest. Turkey has aggressively confiscated passports to target journalists, academics, civil servants, and school teachers. China has barred a women’s human rights defender from travelling outside even her town in Tibet.

Bahrain confiscated the passport of one activist who, upon her return from a Human Rights Council meeting in Geneva, was accused by officials of “false statements” about Bahrain. The United Arab Emirates has held Ahmed Mansoor, a leading human rights defender and blogger and familiar to those in the UN human rights system, incommunicado for nearly this entire year. The government banned him from travelling for years based on his advocacy for democratic reform.

Few governments, apart from Turkey perhaps, can compete with Egypt on this front. I asked Gamal Eid, subject to a travel ban by Egyptian authorities since February of 2016, how it affects his life and work? Eid, one of the leading human rights defenders in the Middle East and the founder of the Arab Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI), has seen his organisation’s website shut down, public libraries he founded (with human rights award money!) forcibly closed, and his bank accounts frozen.

While Eid is recognised internationally for his commitment to human rights, the government accuses him of raising philanthropic funds for ANHRI “to implement a foreign agenda aimed at inciting public opinion against State institutions and promoting allegations in international forums that freedoms are restricted by the country’s legislative system.” He has been separated from his wife and daughter, who fled Egypt in the face of government threats. The ban forced him to close legal offices in Morocco and Tunisia, where he provided defence to journalists, and he lost his green card to work in the United States. He recognises that his situation does not involve the kind of torture or detention that characterises Egypt’s approach to opposition, but the ban has ruined his ability to make a living and to support human rights not just in Egypt but across the Arab world.

Eid is not alone in his country. He estimates that Egypt has placed approximately 500 of its nationals under a travel ban, about sixteen of whom are human rights activists. One of them is the prominent researcher and activist, Hossam Bahgat, founder of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, who faces accusations similar to Eid’s.

Travel bans signal weakness, limited confidence in the power of a government’s arguments, perhaps even a public but quiet concession that, “yes indeed, we repress truth in our country”. While not nearly as painful as the physical weapons of censorship, they undermine global knowledge and debate. They exclude activists and journalists from the kind of training that makes their work more rigorous, accurate, and effective. They also interfere in a direct way with every person’s human right to “leave any country, including one’s own,” unless necessary for reasons such as national security or public order.

All governments that care about human rights should not allow the travel ban to continue to be the silent weapon of censorship – and not just for the sake of Khadija, Zunar, and Gamal, but for those who benefit from their critical voices and work. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Oct 2017 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”96560″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Private view, charity sale

When: Tuesday 21 November 6-8pm

Where: Westminster Reference Library, 35 St Martin’s Street, London WC2H 7HP

Tickets: Free. Registration required via [email protected]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Exhibition

When: 21 November to 7 December, Mon – Fri 10am to 8pm, Sat 10am to 5pm, Sun Closed

Where: Westminster Reference Library, 35 St Martin’s Street, London WC2H 7HP

Tickets: Free.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Workshop

With Banx Cartoons and The Surreal McCoy

When: Saturday 25 November 2-4pm

Where: Westminster Reference Library, 35 St Martin’s Street, London WC2H 7HP

Tickets: Free. Registration required via Eventbrite.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Cartoons and censorship

A discussion with cartoonist Andy Davey, Jodie Ginsberg of Index on Censorship, Guardian and Index on Censorship magazine cartoonist Martin Rowson and via video link: Malaysian cartoonist Zunar and Robert Russell, Cartoonists Rights Network International.

When: Tuesday 28 November 6-8pm

Where: Westminster Reference Library, 35 St Martin’s Street, London WC2H 7HP

Tickets: Free. Registration required via Eventbrite.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Join the UK’s Professional Cartoonists’ Organisation, Cartoonists’ Rights Network International and Index on Censorship – to try to bring the plight of persecuted cartoonists to the fore.

Repressive governments the world over fear cartoonists. Cartoonists get straight to the point.

Images remain in the public eye longer than do acres of type. While we in the UK and Europe generally accept often excoriating depictions of our leaders, this is definitely not the case in the rest of the world. Here, politicians actually applaud critical and often insulting drawings of themselves, sometimes even assembling personal collections thereof. Not so elsewhere. In at least one verified instance, a foreign cartoonist was visited by government agents and had his hands broken. Doubtless there are others.

Repressive governments, fearful of the truth, regularly imprison cartoonists.

This exhibition seeks to do that. Whilst it is not easy to highlight a repressive government’s treatment of any given cartoonist because that government will often react by threatening the cartoonist’s family and friends, any and all proceeds from this exhibition will go towards trying to alleviate the conditions many cartoonists the world over have to live with.

More information[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]