16 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

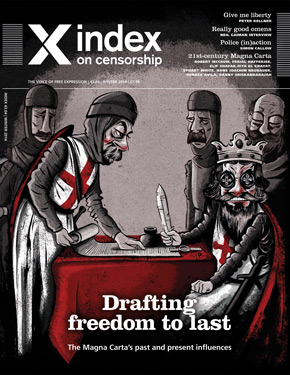

From the winter 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those who plan to attend the Elections – live! session at the festival this year.

Thoughts policed

Have we created a media culture where politicians fear voicing an opinion that’s not the party line? Max Wind-Cowie reports

We are often, rightly, concerned about our politicians censoring us. The power of the state, combined with the obvious temptation to quiet criticism, is a constant threat to our freedom to speak. It’s important we watch our rulers closely and are alert to their machinations when it comes to our right to ridicule, attack and examine them. But here in the West, where, with the best will in the world, our politicians are somewhat lacking in the iron rod of tyranny most of the time, I’m beginning to wonder whether we may not have turned the tables on our politicians to the detriment of public discourse.

Read the full article

From the summer 1995 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those who plan to attend the The body politic: censorship and the female body session at the festival this year.

Deliberately lewd

Erica Jong explains why pornography is to art as prudery is to the censors

Pornographic material has been present in the art and literature of every society in every historical period. What has changed from epoch to epoch – or even from one decade to another – is the ability of such material to flourish publicly and to be distributed legally. After nearly 100 years of agitating for freedom to publish, we find that the enemies of freedom have multiplied, rather than diminished.

Read the full article

From the spring 1987 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those who plan to attend the Banned books: controversy between the covers session at the festival this year.

My book and the school library

Norma Klein, the American writer of children’s books, describes how she successfully defended her Confessions of an Only Child before a school board meeting

I used to feel distinguished, almost honoured, when my young books were singled out to be censored. Now, alas, censorship has become so common in the children’s book field in America that almost no one is left unscathed.

Read the full article

From the summer 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those who plan to attend the Privacy in the digital age session at the festival this year.

Future imperfect

Should concerns about privacy after the NSA revelations change the way we use the web? Jason DaPonte asks the experts about state spying, corporate control and what we can do to protect ourselves

“Government may portray itself as the protector of privacy, but it’s the worst enemy of privacy and that’s borne out by the NSA revelations,” web and privacy guru Jeff Jarvis tells Index.

Read the full article

From the summer 2008 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those who plan to attend the Can writers and artists ever be terrorists? session at the festival this year.

The politics of terror

In the drive to tackle extremism, debate is being undermined and fear is driving the agenda. Conor Gearty makes the case for common sense.

I object to the ‘age of terror’ title. My anxiety about this is that it is already putting people like me at a disadvantage. I am forced to work within an assumption, which is shared by all normal, sensible people, that we live in ‘an age of terror’. Therefore the point of view that I am about to put – about the total appropriateness of the criminal law; about the relative security in which we live; about the fact of our being pretty secure in comparison with many previous generations – is deemed to be sort of eccentric, if not obstructive.

Read the full article

From the spring 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those who plan to attend the War, Censorship and Propaganda: Does It Work session at the festival this year.

Drawing out the dark side

When it comes to depicting war, humour can be a critic’s most dangerous weapon, says Martin Rowson as he trips through the history of cartoons.

As a political cartoonist, whenever I’m criticised for my work being unrelentingly negative, I usually point my accusers towards several eternal truths. One is that cartoons, along with all other jokes, are by their nature knocking copy. It’s the negativity that makes them funny, because, at the heart of things, funny is how we cope with the bad – or negative – stuff.

Read the full article

From the autumn 2013 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those planning to attend the Hidden Voices; Censorship Through Omission session at the festival.

Moving towards inequality

In China, as hundreds of millions leave the countryside to seek employment in the cities, they are left without official jobs, legal protection or school places for their children. Jemimah Steinfeld and Hannah Leung report

When Liang Hong returned to her hometown of Liangzhuang, Henan province, in 2011, she was instantly struck by how many of the villagers had left, finding work in cities all across China. It was then that she decided to chronicle the story of rural migrants. During the next two years she visited over 10 cities, including Beijing, and interviewed around 340 people.

Read the full article

From the spring 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those planning to attend the A New Home: Asylum, Immigration and Exile in Today’s Britain session at the festival.

Escape from Eritrea

As refugees flee one of the world’s most repressive and secretive regimes, Ismail Einashe talks to Eritreans who have reached the UK but who still worry about the risks of speaking out

Television journalist Temesghen Debesai had waited years for an opportunity to make his escape, so when the Eritrean ministry of information sent him on a journalism training course in Bahrain.

Read the full article

From the autumn 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those planning to attend the Technologies of revolution: how innovations are undermining regimes everywhere session at the festival.

From drones to floating smartphones: how technology is helping African journalists investigate

Data journalist Raymond Joseph reports on how low-cost technology is helping African newsrooms get hold of information that they couldn’t previously track

Deep in Mpumalanga province, in the far north-east of South Africa, a poorly resourced newspaper is using a combination of high and low tech solutions to make a difference in the lives of the communities it serves.

Read the full article

From the winter 2013 issue of Index on Censorship. Subscribe.

“Free thinking” for those planning to attend the Faith and education: an uneasy partnership session at the festival.

Defending the right to be offended

For Index on Censorship magazine Samira Ahmed takes a look at 15 years of multiculturalism and how some people’s ideas of it are getting in the way of freedom of expression.

In 1999, the neo-Nazi militant David Copeland planted three nail bombs in London – in Brixton, Brick Lane and Soho – targeting black people, Bangladeshi Muslims and gays and lesbians. Three people died and scores were injured.

Read the full article

Free Thinking! A unique partnership in 2015, Cambridge Festival of Ideas are working with Index on Censorship to offer in-depth articles and follow-up pieces from leading artists, writers and activists on all of our headline events.

• Join us on 24 Oct for Can writers and artists ever be terrorists?

Anti-terror legislation has been used in several countries to effectively gag free speech about sensitive political issues, but can writing or painting be a terrorist act and what role do they play in radicalisation? Join Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas to explore the intersection of art and terrorism.

• Join us on 25 Oct for Question Everything at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas

Question Everything is an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Are we in a drought of new options? Start imagining the world anew with a series of provocateurs. Dissent encouraged. Hosted by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

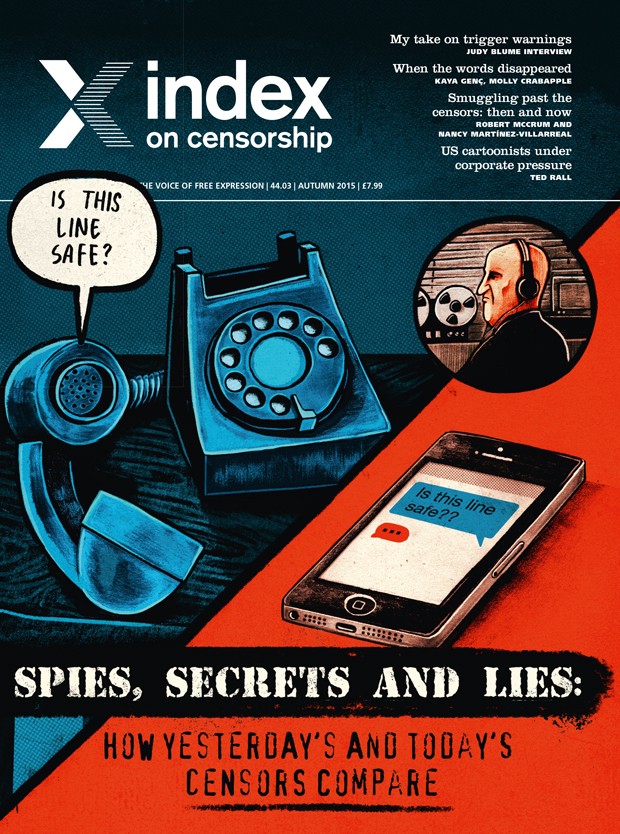

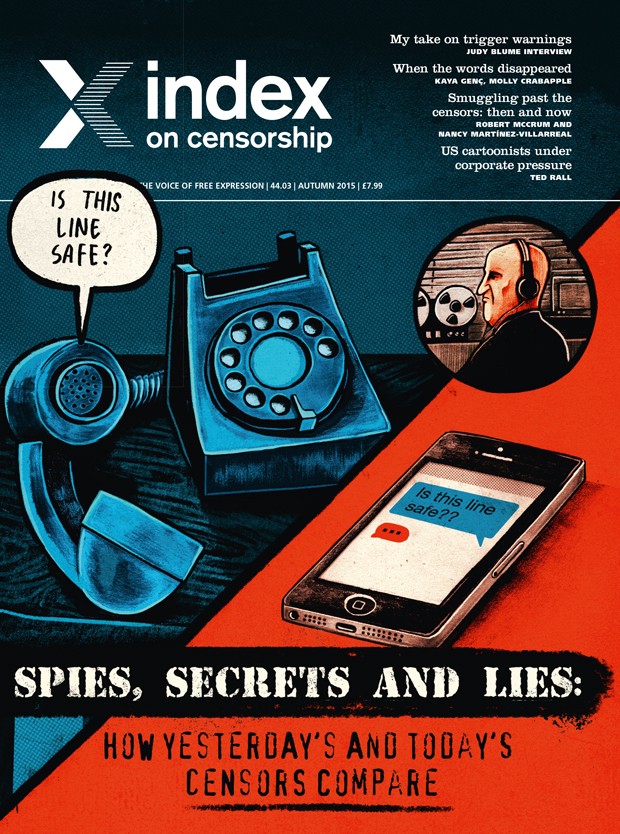

Current issue: Spies, secrets and lies

In the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine Spies, secrets and lies: How yesterday’s and today’s censors compare, we look at nations around the world, from South Korea to Argentina, and discuss if the worst excesses of censorship have passed or whether new techniques and technology make it even more difficult for the public to attain information. Subscribe to the magazine.

|

27 Aug 2015 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Dr Abduljalil al-Singace is a prisoner of conscience and a member of the Bahrain 13, a group of activists arrested by the Bahraini government for their role in peaceful protests in 2011. Dr al-Singace is a blogger, academic, and former Head of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Bahrain. Dr al-Singace is currently serving a life sentence ordered by a military court on 22 June 2011.

The Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry met with Dr al-Singace in 2011 and collected testimony regarding his arbitrary arrest and torture. Despite the existence of this testimony, in 2012 a civilian appeals court refused to investigate Dr al-Singace’s credible allegations of abuse and upheld the military court’s decision. Dr al-Singace has received no compensation for the acts of torture that he suffered, nor have his torturers been held accountable for their actions.

On 21 March 2015, Dr al-Singace went on hunger strike in protest at the collective punishment and acts of torture that police inflicted upon prisoners following a riot in Jau Prison earlier that month. Today, he passed 160 days of hunger strike.

Dr al-Singace suffers from post-polio syndrome and is disabled. In addition to the torture Dr al-Singace has suffered, his medical conditions have deteriorated considerably as a result of his incarceration. Prison and prison hospital authorities have denied him physiotherapy and surgery to his nose and ears. He is currently being held in solitary confinement in a windowless room in Al-Qalaa hospital.

We remind the Bahraini government of its obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Bahrain acceded to in 2006. Under the ICCPR Bahrain must ensure that no individual is subjected to arbitrary detention (Article 9) and that everyone enjoys the right to freedom of expression (Article 19). We demand that the government release all individuals who are arbitrarily detained for exercising their right to free expression, whether through peaceful assembly, online blogging or other means. We also remind the Bahraini government of its obligations arising from the 1984 Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), to which Bahrain is a state party. In 2015, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found that arbitrary detention and torture are used systematically in the criminal justice system of Bahrain.

We, the undersigned NGOs, call on the Bahraini authorities to release Dr Abduljalil al-Singace and all prisoners of conscience in Bahrain.

We further call on the international community, and in particular EU member states and the United States, to demand release of Dr al-Singace.

Background Information

Dr al-Singace has been the target of judicial harassment since 2009, when he was arrested for the first time and charged with participating in a terror plot and inciting hatred on his blog, Al-Faseela, which was subsequently banned by Bahraini Internet Service Providers. Dr al-Singace had blogged prolifically and critically against governmental corruption in Bahrain. He was later pardoned by the King and released, although his blog remained banned in Bahrain.

In August 2010, police arrested Dr al-Singace on his return from London, where he had spoken at an event hosted by the House of Lords on Bahrain. A security official at the time claimed he had “abused the freedom of opinion and expression prevailing in the kingdom.”[1] Following his arrest, Bahraini security forces subjected Dr al-Singace to acts of physical torture.

Dr al-Singace received a second royal pardon alongside other political prisoners in February 2011. He was rearrested weeks later in March following the imposition of a state of emergency and the intervention of the Peninsula Shield Force, an army jointly composed of the six Gulf Cooperation Council countries.

On 22 June 2011, a military court sentenced Dr al-Singace to life imprisonment. He is one of thirteen leading human rights and political activists arrested in the same period, subjected to torture, and sentenced in the same case, collectively known as the “Bahrain 13”. A civilian appeals court upheld the sentence on 22 May 2012. The “Bahrain 13” are serving their prison sentences in the Central Jau Prison. Among the “Bahrain 13”, Ebrahim Sharif, former leader of the secular political society Wa’ad, was released by royal pardon on 19 June 2015, but was rearrested weeks later on 11 July, following a speech in which he criticized the government. He currently faces charges of inciting hatred against the regime. On 9 July 2015, the EU Parliament passed an Urgent Resolution calling for the immediate and unconditional release of the “Bahrain 13” and other prisoners of conscience in Bahrain.

During his time in prison, authorities have consistently denied Dr al-Singace the regular medical treatment he requires for his post-polio syndrome, and have failed to provide him with the surgery he requires as a result of the physical torture to which he was subjected in 2011. Dr al-Singace has an infected ear, suffers from vertigo, and has difficulty breathing.

A combination of poor quality prison facilities, overcrowding, systematic torture and ill-treatment led to a riot in Jau Prison on 10 March 2015. Though a minority of prisoners participated in the riot, police collectively punished prisoners, subjecting many of them to torture. Authorities starved prisoners, arbitrarily beat them, and forced them to sleep in courtyards for days, until large tents were erected. Fifty-seven prisoners are currently on trial for allegedly instigating the riot.

In response to these violations, Dr al-Singace began a hunger strike on 21 March. It has now been 160 days since Dr al-Singace has eaten solid foods, and he has lost over 20 kilograms in weight. Dr al-Singace subsists on water, drinking over four litres daily, fizzy drinks for sugar, nutritional supplements, saline injections and yoghurt drink. His intake is monitored by hospital nurses.

Since the start of Dr al-Singace’s hunger strike, he has been transferred to Al-Qalaa Hospital for prisoners, where he has been kept in solitary confinement in a windowless room and has irregular contact with medical staff and family. Prison authorities prevented condolence visits to attend his nephew’s and mother-in-law’s funerals. Dr al-Singace should be immediately released, allowed to continue his work and given full access to appropriate medical treatment without condition.

Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Human Rights Observatory

Bahrain Human Rights Society

Bahrain Institute of Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Bahrain Press Association

Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights

Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

English Pen

Ethical Journalism Network

European – Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights (EBOHR)

European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR)

Front Line Defenders

Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR)

Index on Censorship

International Forum for Democracy and Human Rights (IFDHR)

Irish Pen

Khiam Rehabilitation Center for Victims of Torture (KRC)

Maharat Foundation

Mothers Legacy Project

No Peace Without Justice

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

Pen International

Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED)

Rafto Foundation

Redress

Reporters Without Borders

Salam for Democracy and Human Rights

Sentinel Human Rights Defenders

Shia Rights Watch

The Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

The European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Tunisia Initiative for Freedom of Expression

Vivarta

Wales PEN Cymru

17 Jun 2015 | Azerbaijan News, mobile, News

Governments don’t really like coming across as authoritarian. They may do very authoritarian things, like lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro democracy campaigners, but they’d rather these people didn’t talk about it. They like to present themselves as nice and human rights-respecting; like free speech and rule of law is something their countries have plenty of. That’s why they’re so keen to stress that when they do lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners, it’s not because they’re journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. No, no: they’re criminals you see, who, by some strange coincidence, all just happen to be journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. Just look at the definitely-not-free-speech-related charges they face.

1) Azerbaijan: “incitement to suicide”

Khadija Ismayilova is one of the government critics jailed ahead of the European Games.

Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was arrested in December for inciting suicide in a former colleague — who has since told media he was pressured by authorities into making the accusation. She is now awaiting trial for “tax evasion” and “abuse of power” among other things. These new charges have, incidentally, also been slapped on a number of other Azerbaijani human rights activists in recent months.

2) Belarus: participation in “mass disturbance”

Belorussian journalist Irina Khalip was in 2011 given a two-year suspended sentence for participating in “mass disturbance” in the aftermath of disputed presidential elections that saw Alexander Lukashenko win a fourth term in office.

3) China: “inciting subversion of state power”

Chinese dissident Zhu Yufu in 2012 faced charges of “inciting subversion of state power” over his poem “It’s time” which urged people to defend their freedoms.

4) Angola: “malicious prosecution”

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Sean Gallagher/Index on Censorship)

Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan investigative journalist and campaigner, has for months been locked in a legal battle with a group of generals who he holds the generals morally responsible for human rights abuses he uncovered within the country’s diamond trade. For this they filed a series of libel suits against him. In May, it looked like the parties had come to an agreement whereby the charges would be dismissed, only for the case against Marques to unexpectedly continue — with charges including “malicious prosecution”.

5) Kuwait: “insulting the prince and his powers”

Kuwaiti blogger Lawrence al-Rashidi was in 2012 sentenced to ten years in prison and fined for “insulting the prince and his powers” in poems posted to YouTube. The year before he had been accused of “spreading false news and rumours about the situation in the country” and “calling on tribes to confront the ruling regime, and bring down its transgressions”.

6) Bahrain: “misusing social media

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

In January nine people in Bahrain were arrested for “misusing social media”, a charge punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison. This comes in addition to the imprisonment of Nabeel Rajab, one of country’s leading human rights defenders, in connection to a tweet.

7) Saudi Arabia: “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”

In late 2014, Saudi women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets, on charges including “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”.

8) Guatemala: causing “financial panic”

Jean Anleau was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing their money from banks.

9) Swaziland: “scandalising the judiciary”

Swazi Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu in 2014 faced charges of “scandalising the judiciary”. This was based on two articles by Maseko and Makhubu criticising corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

10) Uzbekistan: “damaging the country’s image”

Umida Akhmedova (Image: Uznewsnet/YouTube)

Uzbek photographer Umida Akhmedova, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, was in 2009 charged with “damaging the country’s image” over photographs depicting life in rural Uzbekistan.

11) Sudan: “waging war against the state”

Al-Haj Ali Warrag, a leading Sudanese journalist and opposition party member, was in 2010 charged with “waging war against the state”. This came after an opinion piece where he advocated an election boycott.

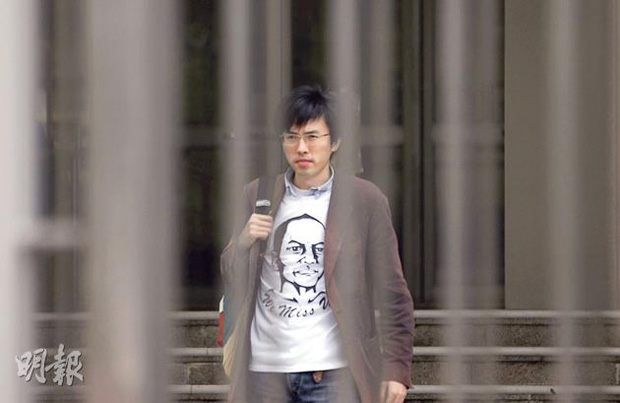

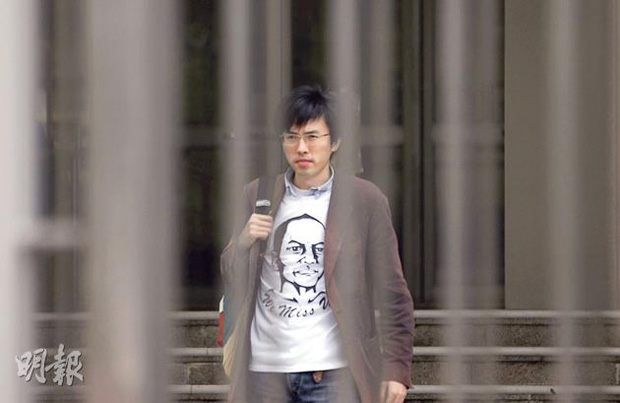

12) Hong Kong: “nuisance crimes committed in a public place”

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

Avery Ng, an activist from Hong Kong, was in 2012 charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place” after throwing a t-shirt featuring a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit.

13) Morocco: compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”

Rachid Nini, a Moroccan newspaper editor, was in 2011 sentenced to a year in prison and a fine for compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”. A number of his editorials had attempted to expose corruption in the Moroccan government.

This article was originally posted on 17 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

1 May 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

On World Press Freedom Day, 116 days after the attack at the office of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo that left 11 dead and 12 wounded, we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to defending the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that we and others may find difficult, or even offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack – a horrific reminder of the violence many journalists around the world face daily in the course of their work – provoked a series of worrying reactions across the globe.

In January, the office of the German daily Hamburger Morgenpost was firebombed following the paper’s publishing of several Charlie Hebdo images. In Turkey, journalists reported receiving death threats following their re-publishing of images taken from Charlie Hebdo. In February, a gunman apparently inspired by the attack in Paris, opened fire at a free expression event in Copenhagen; his target was a controversial Swedish cartoonist who had depicted the prophet Muhammad in his drawings.

A Turkish court blocked web pages that had carried images of Charlie Hebdo’s front cover; Russia’s communications watchdog warned six media outlets that publishing religious-themed cartoons “could be viewed as a violation of the laws on mass media and extremism”; Egypt’s president Abdel Fatah al-Sisi empowered the prime minister to ban any foreign publication deemed offensive to religion; the editor of the Kenyan newspaper The Star was summoned by the government’s media council, asked to explain his “unprofessional conduct” in publishing images of Charlie Hebdo, and his newspaper had to issue a public apology; Senegal banned Charlie Hebdo and other publications that re-printed its images; in India, Mumbai police used laws covering threats to public order and offensive content to block access to websites carrying Charlie Hebdo images. This list is far from exhaustive.

Perhaps the most long-reaching threats to freedom of expression have come from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries, including France, Britain and Germany, issued a statement in which they called on internet service providers to identify and remove online content “that aims to incite hatred and terror”. In the UK, despite the already gross intrusion of the British intelligence services into private data, Prime Minister David Cameron suggested that the country should go a step further and ban internet services that did not give the government the ability to monitor all encrypted chats and calls.

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the state. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On World Press Freedom Day, we, the undersigned, call on all governments to:

• Uphold their international obligations to protect the rights of freedom of expression and information for all, especially journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders to publish, write and speak freely;

• Promote a safe and enabling environment for those who exercise their right to freedom of expression, especially for journalists, artists and human rights defenders to perform their work without interference;

• Combat impunity for threats and violations aimed at journalists and others threatened for exercising their right to freedom of expression and ensure impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations that bring masterminds behind attacks on journalists to justice, and ensure victims and their families have speedy access to appropriate remedies;

• Repeal legislation which restricts the right to legitimate freedom of expression, especially such as vague and overbroad national security, sedition, blasphemy and criminal defamation laws and other legislation used to imprison, harass and silence journalists and others exercising free expression;

• Promote voluntary self-regulation mechanisms, completely independent of governments, for print media;

• Ensure that the respect of human rights is at the heart of communication surveillance policy. Laws and legal standards governing communication surveillance must therefore be updated, strengthened and brought under legislative and judicial control. Any interference can only be justified if it is clearly defined by law, pursues a legitimate aim and is strictly necessary to the aim pursued.

PEN International

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

Albanian Media Institute

Article19

Association of European Journalists

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian PEN

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Centre for Independent Journalism – Malaysia

Danish PEN

Derechos Digitales

Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

English PEN

Ethical Journalism Initiative

Finnish PEN

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Guardian News Media Limited

Icelandic PEN

Index on Censorship

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

International Federation of Journalists

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Malawi PEN

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Institute of Southern Africa

Media Rights Agenda

Media Watch

Mexico PEN

Norwegian PEN

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

PEN Afrikaans

PEN American Center

PEN Catalan

PEN Lithuania

PEN Quebec

Russian PEN

San Miguel Allende PEN

PEN South Africa

Southeast Asian Press Alliance

Swedish PEN

Turkish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

West African Journalists Association

World Press Freedom Committee

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression