21 Jul 2015

Installation image of Spiritual America 2014 at Goldsmiths College. With Permission Xenofon Kavvadias

By Julia Farrington

July 2015

Spiritual America 2014

Xenofon Kavvadias

As part of Index on Censorship’s programme looking into art, law and offence in the UK, this case study looks at Xenofon Kavvadias’s mission to exhibit Spiritual America by Richard Prince in public, effectively reversing the censorship of the image by Tate Modern who removed it from the gallery and the catalogue of their exhibition Pop Life, Art in a Material World 2009-10. Kavvadias called his exhibit Spiritual America 2014 and it formed part of his MA degree show at Goldsmiths College.

The work illustrates many of the issues raised in Index’s Art and the Law pack on Child Protection, giving useful insights into what happens when a work is contested in this area of legislation, the negotiations with the police and how far the law is open to interpretation.

Introduction

Spiritual America by Richard Prince was exhibited as part of The Tate Modern exhibition Pop Life Art: in a Material World, October 1 2009–January 17 2010. The piece is a reproduction of an original 1976 photograph depicting Brooke Shields, aged 10, naked in a bath. The Tate took the work down apparently on the advice by the Obscene Publications Unit of the Metropolitan Police Service that the image might be in breach of the Child Protection Act 1978. Under pressure from the police, the image of the work was also redacted from the catalogue of the show.

A 14 October 2009 BBC report carried a statement from the gallery that said: “In consultation with the artist, Richard Prince, Tate has replaced Spiritual America 1983 with a later version of the work made by him in collaboration with Brooke Shields, Spiritual America IV 2005. Tate is in ongoing discussions with legal advisors about the catalogue.”

Charlotte Higgins and Vikram Dodd writing in The Guardian on 30 September 2009 reported:

The decision by officers to visit Tate Modern is understood to have been made after police chiefs saw coverage of the exhibition in today’s newspapers, rather than as a result of complaints.

Officers met gallery bosses and are also understood to have consulted the Crown Prosecution Service as to whether the image broke obscenity laws.

A Scotland Yard source said the actions of its officers were ‘common sense’ and were taken to pre-empt any breach of the law. The source said the image of Shields was of potential concern because it was of a 10-year-old, and could be viewed as sexually provocative.”

The Tate chose not to include the original picture in Pop Life: Art In A Material World, after seeking legal advice.

Research leading to the presentation of Spiritual America 2014

Kavvadias undertook to display Richard Prince’s Spiritual America in his MA show at Goldsmiths, which he called Spiritual America 2014. As well as displaying a framed replica of the artwork, a record of all his research was available to the viewer to place the image in context. Gaining as full an understanding as possible of the legal and policing positions regarding the removal of the image from the Tate in 2009 was his point of departure.

Freedom of Information Requests

Kavvadias issued FoI requests to the Tate, the Police and the CPS. All FoI correspondence was included in the exhibition.

Key findings:

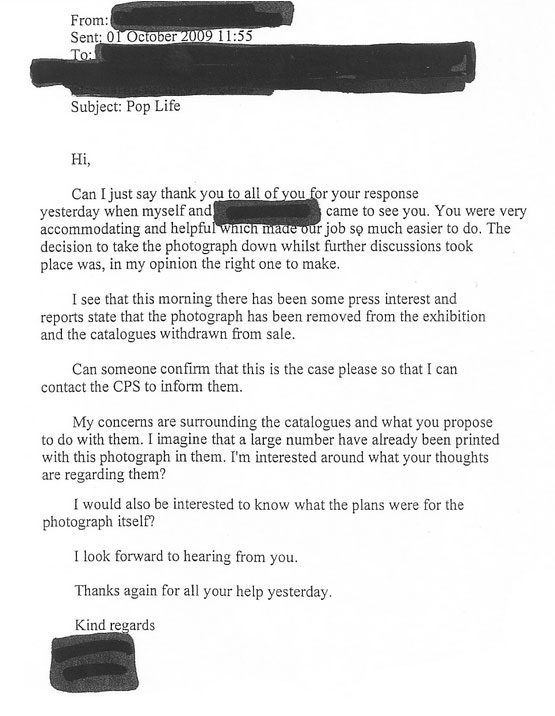

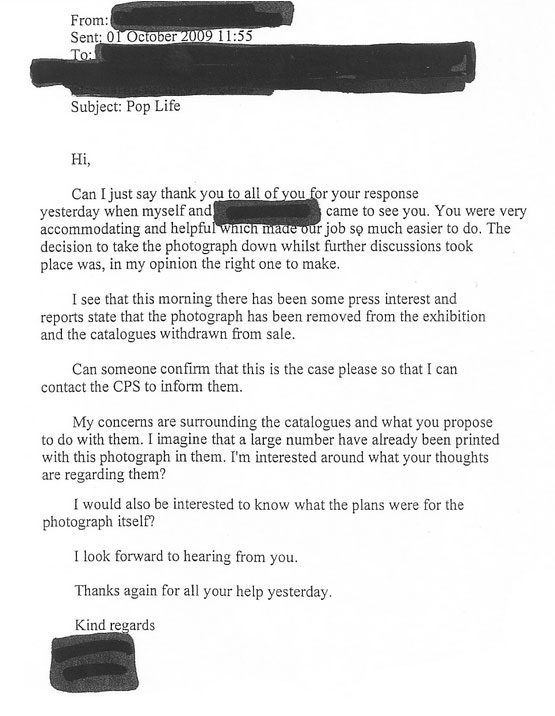

1 October 2009: The police wrote an email to the Tate regarding their visit:

2 October 2009: The police continued to put pressure on the Tate about their plans for the catalogue, writing a follow up email to the one above the next day.

6 October 2009: The Head of Director’s Office, Tate wrote to the trustees:

[Formalities]…we felt that given the important issues at stake (acting within the law while defending artistic freedom of expression) and the level of public interest in the case that we should keep each of you as individual trustees informed.

At the request of the owner and as provided for under our loan agreement with him, we have returned the work to him. In light of this, we have also consulted with the artist and are considering the option of substituting the work with another worked titled Spiritual America IV.

The Tate Enterprises Ltd board will meet…to discuss their position and options with regard to the distribution of the catalogue. Legal advice has been sought to inform their decision from leading counsel and specialist solicitors. …In the meantime the catalogue will continue to be withdrawn”

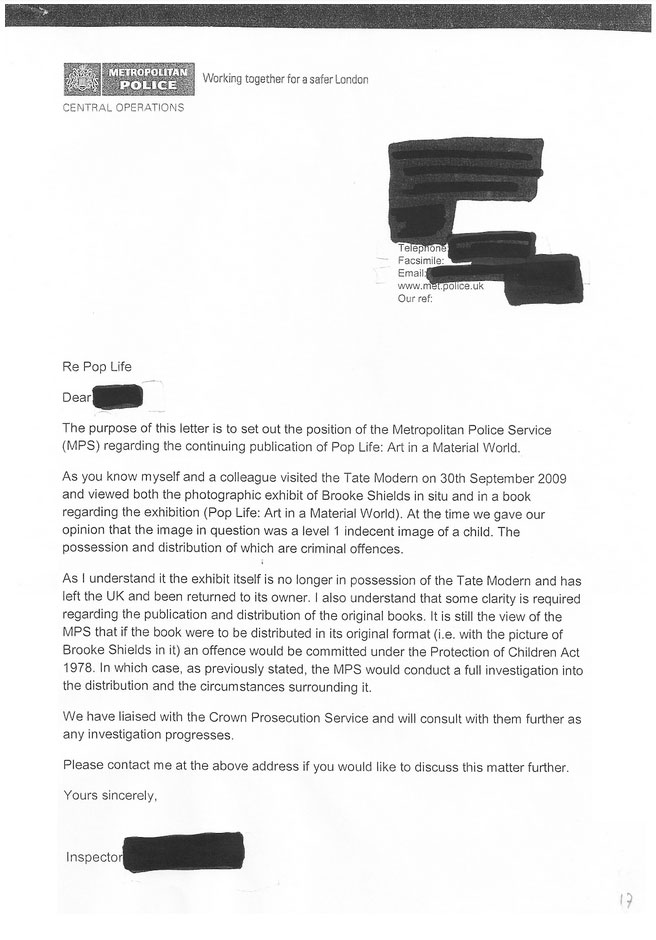

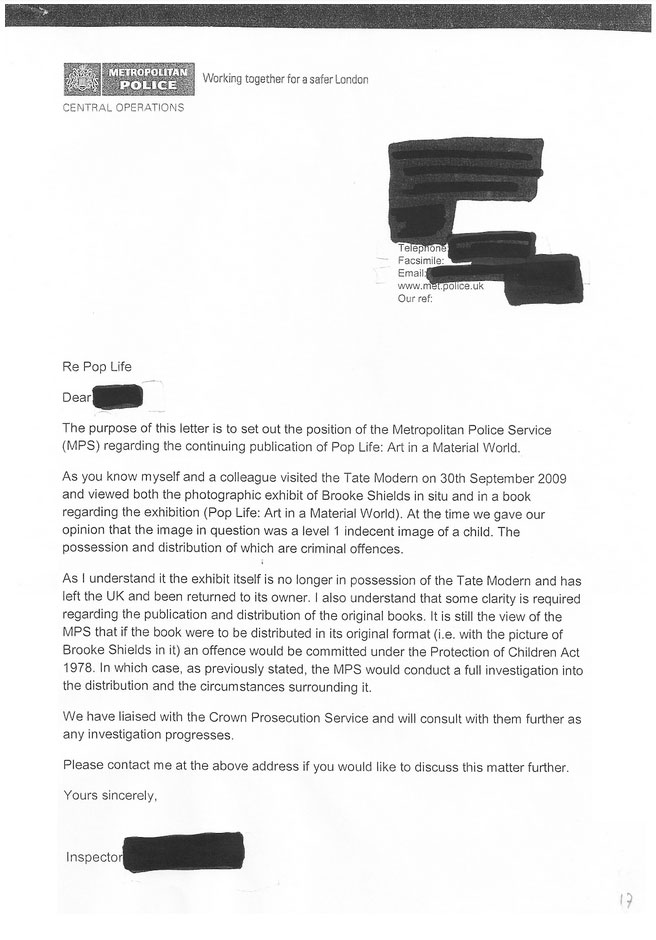

The Metropolitan Police Obscene Publications Unit wrote regarding their position as requested by the Tate:

12 October 2009: The catalogue was removed from sale while the Tate was taking legal advice.

13 October 2009: Metropolitan Police Service Directorate of Public Affairs Central Operations Press Desk, writing to head of communications at the Tate: “I’d just like to raise how categorical you interpret the police advice as having been. We did not state that we definitely considered the image to be indecent but explained that it may be, and that if it was then an offence would be committed if it was displayed. Police can never say when someone will be prosecuted, as that is a decision for the CPS, but did inform yourselves we would consult with the CPS. This is the MPS position as we have been and will continue to, explain to reporters.”

13 October 2009: The plan to obscure the image was in place.

13 October 2009: Tate asked Richard Prince for approval to obscure the image on the catalogue.

16 October 2009: In an email written to the police in support of including the image in the catalogue, Nicholas Serota compiled a list of freely available books featuring “Spiritual America”. Serota, who was Deputy Director of the Tate at the time, wrote: “As outlined already, we presented the work in the exhibition and catalogue because of its art historical significance in the study of 20th century art, as well as its intrinsic artistic merit”.

28 October 2009: The decision was made for the director of the Tate to write to the director of Public Prosecutions seeking clarification on the legal position concerning the work, and guidance on whether a prosecution would follow should the catalogues be distributed again. There is no written reply to this request. However, in 2013, Index spoke to the former DPP, Sir Keir Starmer who had been in post at the time of the controversy, and he said that he received many letters from arts organisations with similar requests but he cannot give advice as to whether a prosecution would follow. This is the work of the courts. However he felt there was a strong case for drawing up guidelines on how CPS reached a decision when considering whether or not to prosecute where artwork is involved.

The legal advice was redacted from the FoI though the explanation of the offences and possible sentencing was made available. See below:

Additional Research

Availability of the image

Kavvadias carried out his own research into the availability of the image in books mentioned in Serota’s list, one of which was written by a professor at Goldsmiths. He researched the libraries of four leading art colleges in London and the British Library, where he easily located the books. He sent an FoI request to the British Library for their position regarding the advice Metropolitan Police gave to Tate. The British Library replied after two months, with a full and considered response robustly defending the books.

Ethics approval from Goldsmiths

The fact that one of the books containing the image was written by a Goldsmiths’ professor reinforced the view held by all of the committee that the Richard Prince picture is an accepted artwork. However, given that this defence failed to convince the legal team working with the Tate, it was not enough itself. They wanted reassurance on three additional concerns:

- the possibility of harm, including damage to reputation of the minor in the original

- that displaying the image might be in breach of copyright

- that the image was not presented in a sensational way that could bring the college into disrepute; they retained the right to withdraw until Kavvadias’ work was in situ in his exhibition

Issue of harm

Kavvadias addressed the issue of harm by presenting the history of the image:

- The original image, by Gary Gross, was commissioned by the Playboy publication Sugar ‘n’ Spice in 1976. Consent was given by Brooke Shield’s mother. She was paid $450 for the rights to the image.

- In 1983 Brooke Shields sought an injunction from the New York State Court of Appeals to bar further publishing of the image. Her motion was denied. According to the court’s ruling, “It should be noted that plaintiff did not contend that the photographs were obscene or pornographic. Her only complaint was that she was embarrassed because ‘they [the photographs] are not me now.'” While the judges found that the photographs were not pornographic, the court left in place an earlier decision that barred the sale of the photo to pornographic magazines.(Shields v. Gross, 58N.Y.2d338,448 N.E.2d108,461 N.Y.S.2d 254,9 Media l Rep. 1466 (N.Y.1983).

- Richard Prince purchased the rights to the image after the court ruling.

- Prince displayed the framed image with the title Spiritual America in 1983 in a New York gallery he rented, amid considerable controversy. Prince later created an edition of 10 prints.

- The image has subsequently been displayed in galleries around the world:

- Valencia, IVAM Centre del Carme, Spiritual America, 1989 (another example exhibited).

Cologne, Museum Ludwig, Ars Pro Domo, May-August 1992, p. 238 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Dirty Data, June-August 1992, p. 75 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, Whitney Museum of American Art; Dusseldorf, Kunstverein; San Francisco, Museum of Modern Art; and Rotterdam, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Richard Prince, May 1992-November 1993, p. 86 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- Munich, Kunstverein and Hamburg, Kunsthaus, Someone Else with my Fingerprints, April-July 1998, p. 75 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, Museum of Modern Art, Fame After Photograph, July-October 1999 (another example exhibited).

- New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, The American Century-Art & Culture 1950-2000, September 1999-February 2000, p. 285, no. 466 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- Minneapolis, Walker Art Center; Paris, Centre Pompidou; Mexican City, Museo Rufino Tamayo and Miami Art Museum, Let’s Entertain, February 2000-November 2001, p. 254 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- Basel, Museum für Gegenwartskunst and Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, December 2001-July 2002, Richard Prince: Photographs, p. 115 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, New Museum of Contemporary Art, East Village USA, December 2004-March 2005, pl. 113, p. 75 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; Minneapolis, Walker Art Center and London, Serpentine Gallery, Richard Prince: Spiritual America, September 2007-Summer 2008, p. 46 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Pictures Generation 1974-1984, April-August 2009, pl. 231 (illustrated, another example exhibited).

- London, Tate Modern; Hamburger Kunsthalle and Ottawa, The National Gallery of Canada, Pop Life: Art in a Material World, October 2009-September 2010, pp. 123 and 196.

- Source: Christies

- In 2005, Brooke Shields, 40, posed for Richard Prince, in a bikini, taken in a similar pose to the original.

- Spiritual America was auctioned for $3,973,000, Sale 3495, at If I Live I’ll See You Tuesday: Contemporary Art Auction 12 May 2014 New York, Rockefeller Plaza

Richard Prince on Spiritual America

“In 1987, after I joined up with Barbara Gladstone, I editioned it. Ten copies and two APs [artist’s proofs]. I had my lab print it on ektacolor paper at 20 x 24”. The first one I sold, was to Stephan, my plumber friend and drummer for the Glenn Branca band. I sold it to him for a hundred dollars and some plumbing work. A couple of years later, I heard he sold that copy to Jay Gorney for four grand. Ten years after that Myer Viceman sold the original 8 x 10” back to Barbara Gladstone for two hundred thousand dollars. Then the 8 x 10” sold to Per Skarsted and later he made a special room for it, (all alone… painted the walls red) and showed it at Art Basel and sold it to Michael Ringier for one million dollars. A couple of years ago Michael lent it to the Tate Modern for some POP show organized by Alison Gingeras and Jack Bankowsky and it was ‘confiscated’ by the London police. The Tate didn’t do much protesting… they caved in to the ‘authorities’ and let them cart it away. It was never re-hung at the Tate and it was eventually returned to Michael Ringier. (Last I heard, Michael lives with Spiritual America in his home outside of Zurich).” Source: ASX

Copyright Infringement

As for possible copyright infringement, because Kavvadias was making a replica of the entire work, including placing it in a frame similar to the one used by Richard Prince, he had to demonstrate clearly to the university that he had the relevant permissions. Given that Richard Prince based his career on copying images and putting them into a new context, Kavvadias did not anticipate a problem. Kavvadias was using the image under Fair Use in US Copyright law for non-commercial and/or academic purpose. However, in order to reassure Goldsmiths, he took two steps:

He tweeted Richard Prince that he had been accused of copying his work. Richard Prince retweeted his message.

Kavvadias wrote to Prince’s London gallery informing them that he was attempting to legitimise the artist’s work that had been criminalised in the UK. They wished him luck.

Legal Advice — Second Opinion

Kavvadias interviewed lawyer Mark Stephens of Finers Stephens Innocent on 4 February 2013, regarding the legal advice given to the Tate to redact the image. Stephens made it clear he didn’t think there was any possibility that the CPS would have recommended a prosecution. Taking the CPS three stage test of whether to prosecute: the first, which asks is there sufficient evidence, is covered, because the image is the evidence. But he claimed it would have failed the other two:

- “that there has to be better than 50% chance of a successful prosecution: ‘Although I could see several charges that could be laid, [they] would be very difficult to succeed.'”

- “that it has to be in the public interest. Stephens stated that, in his opinion, it was not in the public interest to ‘bring the prosecution against Britain’s foremost cultural institution when the image has been around since the seventies, the culture across the planet have shown it and exhibited it without complaint. Even if you prosecute successfully this particular institution, which was displaying just one copy of this image, this was not going to eradicate the image, this was not going to eradicate any harm. If there was any harm, that occurred when this image went viral, effectively when it went on the internet…'”

The Police

Kavvadias wrote to the police informing them that he intended to display this work as part of his Masters thesis at Goldsmiths and gave them the dates. He didn’t ask them for advice or permission. He kept the email trail as evidence of his transparency. They didn’t respond.

Letter: Academic freedom is under threat and needs urgent protection

26 Jun 2015 | Academic Freedom, Academic Freedom Letters, Magazine, News, Turkey Letters, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

With threats ranging from “no-platforming” controversial speakers, to governments trying to suppress critical voices, and corporate controls on research funding, academics and writers from across the world have signed Index on Censorship’s open letter on why academic freedom needs urgent protection.

Academic freedom is the theme of a special report in the summer issue of Index on Censorship magazine, featuring a series of case studies and research, including stories of how setting an exam question in Turkey led to death threats for one professor, to lecturers in Ukraine having to prove their patriotism to a committee, and state forces storming universities in Mexico. It also looks at how fears of offence and extremism are being used to shut down debate in the UK and United States, with conferences being cancelled and “trigger warnings” proposed to flag potentially offensive content.

Signatories on the open letter include authors AC Grayling, Monica Ali, Kamila Shamsie and Julian Baggini; Jim Al-Khalili (University of Surrey), Sarah Churchwell (University of East Anglia), Thomas Docherty (University of Warwick), Michael Foley (Dublin Institute of Technology), Richard Sambrook (Cardiff University), Alan M. Dershowitz (Harvard Law School), Donald Downs (University of Wisconsin-Madison), Professor Glenn Reynolds (University of Tennessee), Adam Habib (vice chancellor, University of the Witwatersrand), Max Price (vice chancellor of University of Cape Town), Jean-Paul Marthoz (Université Catholique de Louvain), Esra Arsan (Istanbul Bilgi University) and Rossana Reguillo (ITESO University, Mexico).

The letter states:

We the undersigned believe that academic freedom is under threat across the world from Turkey to China to the USA. In Mexico academics face death threats, in Turkey they are being threatened for teaching areas of research that the government doesn’t agree with. We feel strongly that the freedom to study, research and debate issues from different perspectives is vital to growing the world’s knowledge and to our better understanding. Throughout history, the world’s universities have been places where people push the boundaries of knowledge, find out more, and make new discoveries. Without the freedom to study, research and teach, the world would be a poorer place. Not only would fewer discoveries be made, but we will lose understanding of our history, and our modern world. Academic freedom needs to be defended from government, commercial and religious pressure.

Index will also be hosting a debate in London, Silenced on Campus, on 1 July, with panellists including journalist Julie Bindel, Nicola Dandridge of Universities UK, and Greg Lukianoff, president and CEO of Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, US.

To attend for free, register here.

If you would like to add your name to the open letter, email [email protected]

A full list of signatories:

Professor Mike Adams, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, USA

Monica Ali, author

Lyell Asher, associate professor, Lewis & Clark College, USA

Professor Jim Al-Khalili OBE, University of Surrey, UK

Esra Arsan, associate professor, Istanbul Bilgi University, Turkey

Julian Baggini, author

Professor Mark Bauerlein, Emory University, USA

David S. Bernstein, publisher, USA

Robert Bionaz, associate professor, Chicago State University, USA

Susan Blackmore, visiting professor, University of Plymouth, UK

Professor Jan Blits, professor emeritus, University of Delaware, USA

Professor Enikö Bollobás, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary

Professor Roberto Briceño-León, LACSO, Caracas, Venezuela

Simon Callow, actor

Professor Sarah Churchwell, University of East Anglia, UK

Professor Martin Conboy, University of Sheffield, UK

Professor Thomas Cushman, Wellesley College, USA

Professor Antoon De Baets, University of Groningen, Holland

Professor Alan M Dershowitz, Harvard Law School, USA

Rick Doblin, Association for Psychedelic Studies, USA

Professor Thomas Docherty, University of Warwick, UK

Professor Donald Downs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

Professor Alice Dreger, Northwestern University, USA

Michael Foley, lecturer, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Professor Tadhg Foley, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

Nick Foster, programme director, University of Leicester, UK

Professor Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

AC Grayling, author

Professor Randi Gressgård, University of Bergen, Norway

Professor Adam Habib, vice-chancellor, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Professor Gerard Harbison, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Adam Hart Davis, author and academic, UK

Professor Jonathan Haidt, NYU-Stern School of Business, USA

John Earl Haynes, retired political historian, Washington, USA

Professor Gary Holden, New York University, USA

Professor Mickey Huff, Diablo Valley College, USA

Professor David G. Hoopes, California State University, USA

Philo Ikonya, poet

James Ivers, lecturer, Eastern Michigan University, USA

Rachael Jolley, editor, Index on Censorship

Lee Jones, senior lecturer, Queen Mary University of London, UK

Stephen Kershnar, distinguished teaching professor, State University of New York, Fredonia, USA

Professor Laura Kipnis, Northwestern University, USA

Ian Kilroy, lecturer, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Val Larsen, associate professor, James Madison University, USA

Wendy Law-Yone, author

Professor Michel Levi, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Ecuador

Professor John Wesley Lowery, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA

Greg Lukianoff, president and chief executive, Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (Fire), USA

Professor Tetyana Malyarenko, Donetsk State Management University, Ukraine

Ziyad Marar, global publishing director, Sage

Charlie Martin, editor PJ Media, UK

Jean-Paul Marthoz, senior lecturer, Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium

Professor Alan Maryon-Davis, King’s College London, UK

John McAdams, associate professor, Marquette University, USA

Timothy McGuire, associate professor, Sam Houston State University, USA

Professor Tim McGettigan, Colorado State University, USA

Professor Lucia Melgar, professor in literature and gender studies, Mexico

Helmuth A. Niederle, writer and translator, Germany

Professor Michael G. Noll, Valdosta State University, USA

Undule Mwakasungula, human rights defender, Malawi

Maureen O’Connor, lecturer, University College Cork, Ireland

Professor Niamh O’Sullivan, curator of Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, and Quinnipiac University, Connecticut, USA

Behlül Özkan, associate professor, Marmara University, Turkey

Suhrith Parthasarathy, journalist, India

Professor Julian Petley, Brunel University, UK

Jammie Price, writer and former professor, Appalachian State University, USA

Max Price, vice-chancellor, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Clive Priddle, publisher, Public Affairs

Professor Rossana Reguillo, ITESO University, Mexico

Professor Glenn Reynolds, University of Tennessee College of Law, USA

Professor Matthew Rimmer, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Professor Paul H. Rubin, Emory University, USA

Andrew Sabl, visiting professor, Yale University, USA

Alain Saint-Saëns, director,Universidad Del Norte, Paraguay

Professor Richard Sambrook, Cardiff University, UK

Luís António Santos, University of Minho, Portugal

Professor Francis Schmidt, Bergen Community College, USA

Albert Schram, vice chancellor/CEO, Papua New Guinea University of Technology

Victoria H F Scott, independent scholar, Canada

Kamila Shamsie, author

Harvey Silverglate, lawyer and writer, Massachusetts, USA

William Sjostrom, director and senior lecturer, University College Cork, Ireland

Suzanne Sisley, University of Arizona College of Medicine, USA

Chip Stewart, associate dean of the Bob Schieffer College of Communication, Texas Christian University, USA

Professor Nadine Strossen, New York Law School, USA

Professor Dawn Tawwater, Austin Community College, USA

Serhat Tanyolacar, visiting assistant professor, University of Iowa, USA

Professor John Tooby, University of California, USA

Meena Vari, Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore, India

Professor Leland Van den Daele, California Institute of Integral Studies, USA

Professor Eugene Volokh, UCLA School of Law, USA

Catherine Walsh, poet and teacher, Ireland

Christie Watson, author

Ray Wilson, author

Professor James Winter, University of Windsor, Canada

Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

29 Apr 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović, at the Permanent Council in Vienna, 16 January 2014. (Photo: OSCE)

Anniversaries and commemorations are times to reflect, judge and move forward. So it is with World Press Freedom Day, which we note for the 22nd time this year amid worldwide evidence of hostility toward the media.

The date of 3 May was set aside by the UN General Assembly in 1993 to foster free, independent, pluralistic media worldwide.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the largest regional security organisation in the world, just four years later in 1997 created the position I now hold, the Representative on Freedom of the Media. The position was established expressly to help countries that are members of the organisation (which includes all of Europe, the countries of the former Soviet Union and Mongolia, as well as the United States and Canada) implement their promises to uphold the rights to free expression and free media.

It is my job to advocate for these two concepts. It is also my job to help, cajole and sometimes plead with the 57 nations in the organisation to simply live up to their promises to provide the environment in which free expression and free media can flourish.

Over the past 18 years only three people have held the position of Representative. As I enter my sixth and last year in this position, the time has come to reflect on the state of media freedom and to analyse the overall health of free expression across the OSCE region.

To do so, I needed a base from which to judge. I found that by returning to the very first public statement issued by the Representative’s office, then headed by German politician Freimut Duve, on 7 September 1998. It announced, ironically, that Duve had been denied a visa by authorities in Belgrade to visit the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, to lobby the government to change its policy of denying visas to reporters from other countries, some of whom were considered foreign intelligence agents.

The Helsinki Final Act of 1975, the very document that eventually brought the OSCE into existence, expressly called for improving the working conditions for journalists, which included examining “in a favorable spirit and within a suitable and reasonable time scale requests from journalists for visas” and to “grant to permanently accredited journalists…on the basis of arrangements, multiple entry and exit visas for specified periods”.

Duve wrote in the public statement: “Tito himself, as President of the former Yugoslavia, signed in 1975 his country’s acceptance of the principles and commitments of the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe.”

Those commitments expressly included the right of journalists to work internationally.

Promises made. Promises not kept.

Have things changed over the years?

The fact that you are reading this posting identifies you as someone well aware of the precarious position journalists and the media find themselves in today. They face a litany of problems, none of which is bigger than the issue of life itself.

The year 2015 hardly had started when eight journalists for the French magazine Charlie Hebdo were murdered in their office in Paris – over the depiction of a religious figure. Two weeks later, a discussion group in Copenhagen convened to talk about the Paris incident came under gunfire with another person killed. So much for free media. So much for free expression.

But we all know that while homicidal violence against journalists is the most drastic form of attack on free media, it is not the only one. Across the OSCE region media is subject to all nature of offences: criminal defamation laws that put reporters in jail for rooting out corruption in public places; cyber-attacks that plague internet media sites; new laws that are being adopted to criminalise free expression in the name of fighting terrorism; and increasing regulation of the internet in an effort by authoritarian governments to squelch media and free expression advocates.

The simple violations of media rights continue, too. In the past 12 months I have written to authorities and issued public statement on at least six occasions condemning the refusal of governments in the OSCE region to grant visas to foreign-based reporters. Have things really changed in 2015 from 1998? Only the countries involved; not the practices.

But even if my judgment on the past 18 years is harsh, media freedom advocates, such as me, must continue to move forward and provide the defenses necessary for free expression and free media to flourish. Complacency is not an option.

Solidarity, however, is.

For example, three rapporteurs on free expression from the United Nations, the Organization of American States and the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights and I annually issue a joint declaration on a topic related to free expression. Those declarations now are seeing their way into decisions of national and international bodies, including judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. This is real progress. Decisions upholding citizens’ rights under Article 10 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms are real results.

And all of us must continue to raise the issue of the rights of media before national legislatures. Public awareness campaigns on behalf of media can be effective tools to prod elected officials to spend the resources, including political capital, necessary to build environments conducive to free expression. Elected officials and their appointed, often nameless and faceless bureaucrats, can be taught and encouraged to write good laws and appoint good law enforcement authorities, including police, prosecutors and judges, to interpret those laws in a fashion that will provide oxygen for those who champion free expression.

It is easy to become disillusioned and depressed by the daily fare of media issues. We should recognise the perilous state of free media and free expression in many spots in the world. But we never should lose our focus. We should take note of this date and make a personal commitment to stand for the basic human rights of free expression and free media – this year and the next and the years after that.

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This column was posted on 29 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org