17 Jan 2025 | Asia and Pacific, News, Vietnam, Volume 53.04 Winter 2024

This article first appeared in Volume 53, Issue 4 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Unsung Heroes: How musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

Hoàng Minh Tường has published 17 novels. Seven of these have been banned from re-publication or circulation in Vietnam and two had to be published overseas due to political sensitivities. But the Hanoi-based writer remains upbeat.

“I have been blessed by the heavenly gods,” said the 76-year-old, who used to work as a teacher and journalist. “Many times, I was afraid that I might be imprisoned. Yet I still remain alive.”

The award-winning novelist is currently seeking help to have his best- known novel Thời của Thánh Thần (The Time of the Gods) translated into English. On release in 2008, it was widely regarded as a literary phenomenon yet was immediately recalled and has been banned ever since.

Hoàng, and many other writers I spoke to for this article, agreed that censorship is accepted as part of living and working in Vietnam, where the Communist Party monopolises the publishing industry. The 2012 Publishing Law emphasises the need to “fight against all thoughts and behaviour detrimental to the national interests and contribute to the construction and defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam”.

But censorship of fiction is just one part of the country’s free expression quandary. Reporters Without Borders has long categorised Vietnam as being among the worst countries for freedom of the press. The Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC) is the government agency responsible for state management of press, publishing and printing activities. Writers have to regularly negotiate with censors – and then creatively rise above them or patiently wait for the individuals or agencies in charge to change their minds.

Living with censorship

Hoàng, a Communist Party member, said that The Time of the Gods, written between 2005 and 2008, was a turning point in his literary career, which has spanned three decades.

“After finishing writing the book in 2008, my biggest concern was how to get it published,” he said. “I gave it to three influential friends in three publishing houses, all of whom rejected it because if they published it they would be sent to jail.”

In his banned novel, the characters are multi-faceted. Four brothers navigate different sides of armed conflicts, align with various factions and transcend the simplistic “us versus the enemy” narrative often depicted by the Communist Party.

They endure many of the hidden, historical tribulations of Vietnam – from the Maoist land reform in the 1950s, which seized agricultural land and property owned by landlords for redistribution, to the fall of Saigon in 1975, which ended the Vietnam War and resulted in a mass exodus to escape the victorious communist regime.

“The story of a family is not just the story of a single family but the story of the times, the story of the nation, the story of the two communist and capitalist factions, of the North and South regions of Vietnam and the United States,” said Hoàng. “Perhaps that is why, for the past 15 years, tens of thousands of illegal copies of the book have been printed and people still seek it out to read.”

The ban has created fertile ground for black market circulation, he said, with online and offline pirated copies often full of mistakes. There have never been any official government documents justifying the book ban, nor has there been any explanation for the sensitivities surrounding his works. He asserted that this lack of transparency and accountability was a common occurrence for novelists. “Most of the bans [on my books] were purely by word of mouth,” he said.

For years, Hoàng has communicated with editors at the state-owned Writers’ Association Publishing House (which originally published the book), but to no avail. However, the novel has made its way to global audiences, being translated into Korean, French, Japanese and Mandarin Chinese.

His 2014 novel Nguyên khí (Vitality) was originally rejected for publication, and again reasons were not disclosed. The story, revolving around Nguyễn Trãi – a 15th century historical figure who was a loyal and skilled official falsely accused of killing an emperor – symbolises the still strained relationship between single-party rule and patriotic intellectuals. In response, Hoàng revised the narrative of the novel by getting rid of a character – a security agent doubling as a censor and eavesdropper. He retitled the work to The Tragedy of a Great Character, a rebranding that managed to pass through pre-print censorship. Subsequently, in 2019, the book was published and sold out. However, its previous ban was soon recognised, so it didn’t secure a permit for republication.

Learning from history

In his 2022 article Banishing the Poets: Reflections on Free Speech and Literary Censorship in Vietnam, Richard Quang Anh Trần, assistant professor of Southeast Asian studies at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, concluded that the literary landscape in Vietnam was “as limited as political speech itself”.

“The boundaries of permissible speech, moreover, are ever changing that one may find oneself caught in the crosshairs and on the wrong side at any given moment,” he wrote.

Trần identified two turning points when writers were fooled into believing that the Communist Party had allowed them to challenge the established literary norms of serving the party. The first occurred in the 1950s, during a cultural-political movement in Hanoi, called the Nhân Văn-Giai Phẩm Affair. A group of party-loyal writers and intellectuals launched two journals, Nhân Văn (Humanity) and Giai Phẩm (Masterpieces). They sought to convince the party of the need for greater artistic and intellectual freedom. Despite their distinguished service to the state, they were condemned in state media and their publications were banned.

The second case came in the late 1980s and early 1990s during Doi Moi (the Renovation Period), a series of economic and political reforms which started in 1986. Vietnam’s market liberalisation breathed new life into war-centric literature, and many writers crafted brilliant post-war novels that challenged prevailing narratives – but their works were censored. This was done through limiting the number of approved copies, recalling and confiscating books from libraries and bookshops, and destroying original drafts.

Censorship was at its worst when the party decided to burn the books of those it regarded as its enemies. Following the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975, it embarked on a campaign to eliminate what it classified as decadent and reactionary culture, including many books and magazines published in the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).

“South Vietnamese publications were the main target, plus much of popular music, movies and the fine arts,” said Dr Tuấn Hoàng, associate professor of great books at Pepperdine University’s Seaver College in California. “Government workers entered businesses and private residences suspected of having such materials and took away what they could find.”

“Those materials were burned or recycled at factories,” he said. “Citizens were urged to give up banned materials to the government, or to destroy them themselves. A lot of materials were therefore destroyed in the first few years after the war.”

But some materials were hidden, circulated clandestinely or sold on the black market. Phạm Thị Hoài is one of the most celebrated writers of the post- Renovation Period, whose debut novel The Crystal Messenger was a success both at home and abroad. The first edition (1988) and second edition (1995) were published by the Writers’ Association Publishing House, bar a few censored paragraphs, according to Phạm. But it was later banned by the government.

After leaving Vietnam for Germany, in 2001 she established Talawas, an online forum dedicated to reviving literary works by Vietnamese writers. She says she has been banned from travelling back to her home country since 2004, a fact she attributes to Talawas and her literary works, which have been ambiguously deemed to be “sensitive”. Her books have not been permitted to be republished in Vietnam.

“A few years ago, a friend in the publishing industry also tried to inquire about reprinting a collection of my short stories, which were entirely about love, but no publishing house accepted it,” she said.

In 2018, the government introduced a new cybersecurity law, which has made censorship worse. Critical voices that challenge the state’s version of history online are deemed to be hostile forces that are seeking to discredit the party’s revolutionary achievements.

Appreciate, don’t criticise

Censorship also makes its way into education as, in Vietnam, literature is first and foremost intended to inculcate party- defined patriotism into young minds.

According to Dr Ngọc, a high-school literature teacher in Hanoi, Vietnamese authors who are featured in school textbooks normally have very “red” (communist) backgrounds or hold party leadership positions. She added that the higher an author’s position in government, the more focus is given to their work in textbooks. “Many great writers were unfortunately not selected for the literature textbooks,” she said.

Ngọc provides tutoring for high- school students to help them prepare for their national entrance exams. These exams mostly focus on wartime hardship and heroism. Students’ responses need to show that they revere communist leaders and revile invaders. But this teaching method is not best placed to help them appreciate literature.

But ill-fated books still find their way to readers, often through the black market. Phương (not her real name) has been selling books in Hanoi for the past two decades. She says that every now and then people still look for banned books, which she collects and sells. However, these are reserved only for her closest customers.

“I would not sell sensitive books to a random buyer,” she said. “They might be disguised security agents trying to recall the book from the market.”

25 Jan 2023 | Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Belarus, Belgium, Botswana, Burma, China, Cuba, Czech Republic, Denmark, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Index Index, Ireland, Laos, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Netherlands, News, Nicaragua, North Korea, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Switzerland, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, United States, Yemen

A major new global ranking index tracking the state of free expression published today (Wednesday, 25 January) by Index on Censorship sees the UK ranked as only “partially open” in every key area measured.

In the overall rankings, the UK fell below countries including Australia, Israel, Costa Rica, Chile, Jamaica and Japan. European neighbours such as Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Denmark also all rank higher than the UK.

The Index Index, developed by Index on Censorship and experts in machine learning and journalism at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), uses innovative machine learning techniques to map the free expression landscape across the globe, giving a country-by-country view of the state of free expression across academic, digital and media/press freedoms.

Key findings include:

-

The countries with the highest ranking (“open”) on the overall Index are clustered around western Europe and Australasia – Australia, Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland.

-

The UK and USA join countries such as Botswana, Czechia, Greece, Moldova, Panama, Romania, South Africa and Tunisia ranked as “partially open”.

-

The poorest performing countries across all metrics, ranked as “closed”, are Bahrain, Belarus, Burma/Myanmar, China, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Laos, Nicaragua, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

-

Countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates performed poorly in the Index Index but are embedded in key international mechanisms including G20 and the UN Security Council.

Ruth Anderson, Index on Censorship CEO, said:

“The launch of the new Index Index is a landmark moment in how we track freedom of expression in key areas across the world. Index on Censorship and the team at Liverpool John Moores University have developed a rankings system that provides a unique insight into the freedom of expression landscape in every country for which data is available.

“The findings of the pilot project are illuminating, surprising and concerning in equal measure. The United Kingdom ranking may well raise some eyebrows, though is not entirely unexpected. Index on Censorship’s recent work on issues as diverse as Chinese Communist Party influence in the art world through to the chilling effect of the UK Government’s Online Safety Bill all point to backward steps for a country that has long viewed itself as a bastion of freedom of expression.

“On a global scale, the Index Index shines a light once again on those countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates with considerable influence on international bodies and mechanisms – but with barely any protections for freedom of expression across the digital, academic and media spheres.”

Nik Williams, Index on Censorship policy and campaigns officer, said:

“With global threats to free expression growing, developing an accurate country-by-country view of threats to academic, digital and media freedom is the first necessary step towards identifying what needs to change. With gaps in current data sets, it is hoped that future ‘Index Index’ rankings will have further country-level data that can be verified and shared with partners and policy-makers.

“As the ‘Index Index’ grows and develops beyond this pilot year, it will not only map threats to free expression but also where we need to focus our efforts to ensure that academics, artists, writers, journalists, campaigners and civil society do not suffer in silence.”

Steve Harrison, LJMU senior lecturer in journalism, said:

“Journalists need credible and authoritative sources of information to counter the glut of dis-information and downright untruths which we’re being bombarded with these days. The Index Index is one such source, and LJMU is proud to have played our part in developing it.

“We hope it becomes a useful tool for journalists investigating censorship, as well as a learning resource for students. Journalism has been defined as providing information someone, somewhere wants suppressed – the Index Index goes some way to living up to that definition.”

6 Aug 2021 | Canada, Eritrea, Hong Kong, Netherlands, News, Philippines, Syria, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117182″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

The number of journalists killed while doing their work rose in 2020. It’s no wonder, then, that a team of internationally acclaimed lawyers are advising governments to introduce emergency visas for reporters who have to flee for their lives when work becomes too dangerous.

The High Level Panel of Legal Experts on Media Freedom, a group of lawyers led by Amal Clooney and former president of the UK Supreme Court Lord Neuberger, has called for these visas to be made available quickly. The panel advises a coalition of 47 countries on how to prevent the erosion of media freedom, and how to hold to account those who harm journalists.

At the launch of the panel’s report, Clooney said the current options open to journalists in danger were “almost without exception too lengthy to provide real protection”. She added: “I would describe the bottom line as too few countries offer ‘humanitarian’ visas that could apply to journalists in danger as a result of their work.”

The report that includes these recommendations was written by barrister Can Yeğinsu. It has been formally endorsed by the UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights special rapporteur for freedom of expression, and the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute.

As highlighted by the recent release of an International Federation of Journalists report showing 65 journalists and media workers were killed in 2020 – up 17 from 2019 – and 200 were jailed for their work, the issue is incredibly urgent.

Index has spoken to journalists who know what it is like to work in dangerous situations about why emergency visas are vital, and to the lawyer leading the charge to create them.

Syrian journalist Zaina Erhaim, who has worked for the BBC Arabic Service, has reported on her country’s civil war. She believes part of the problem for journalists forced to flee because of their work is that many immigration systems are not set up to be reactive to those kinds of situations, “because the procedures for visas and immigration is so strict, and so slow and bureaucratic”.

Erhaim, who grew up in Idlib in Syria’s north-west, went on to report from rebel-held areas during the civil war, and she also trained citizen journalists.

The journalist, who won an Index award in 2016, has been threatened with death and harassed online. She moved to Turkey for her own safety and has spoken about not feeling safe to report on Syria at times, even from overseas, because of the threats.

She believes that until emergency visas are available quickly to those in urgent need, things will not change. “Until someone is finally able to act, journalists will either be in hiding, scared, assassinated or already imprisoned,” she said.

“Many journalists don’t even need to emigrate when they’re being targeted or feel threatened. Some just need some peace for three or four months to put their mind together, and think what they’ve been through and decide whether they should come back or find another solution.”

Erhaim, who currently lives in the UK, said it was also important to think about journalists’ families.

Eritrean journalist Abraham Zere is living in exile in the USA after fleeing his country. He feels the visa proposal would offer journalists in challenging political situations some sense of hope. “It’s so very important for local journalists to [be able to] flee their country from repressive regimes.”

Eritrea is regularly labelled the worst country in the world for journalists, taking bottom position in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index 2021, below North Korea. The RSF report highlights that 11 journalists are currently imprisoned in Eritrea without access to lawyers.

Zere said: “Until I left the country, for the last three years I was always prepared to be arrested. As a result of that constant fear, I abandoned writing. But if I were able to secure such a visa, I would have some sense of security.”

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick is a journalist formerly based in Hong Kong who has recently moved to Taiwan. He has worked as an editor for the Hong Kong Free Press, as well as for the South China Morning Post, Time and The Wall Street Journal.

“I wasn’t facing any immediate threats of violence, harassment, that sort of thing, [but] the environment for the journalists in Hong Kong was becoming a lot darker and a lot more dire, and [it was] a lot more difficult to operate there,” he said.

He added that although his need to move wasn’t because of threats, it had illustrated how difficult a relocation like that could be. “I tried applying from Hong Kong. I couldn’t get a visa there. I then had to go halfway around the world to Canada to apply for a completely different visa there to get to Taiwan.”

He feels the panel’s recommendation is much needed. “Obviously, journalists around the world are facing politically motivated harassment or prosecution, or even violence or death. And [with] the framework as it is now, journalists don’t really fit very neatly in it.”

As far as the current situation for journalists in Hong Kong is concerned, he said: “It became a lot more dangerous reporting on protests in Hong Kong. It’s immediate physical threats and facing tear gas, police and street clashes every day. The introduction of the national security law last year has made reporting a lot more difficult. Virtually overnight, sources are reluctant to speak to you, even previously very vocal people, activists and lawyers.”

In the few months since the panel launched its report and recommendations, no country has announced it will lead the way by offering emergency visas, but there are some promising signs from the likes of Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. [The Dutch House of Representatives passed a vote on facilitating the issuance of emergency visas for journalists at the end of June.]

Report author Yeğinsu, who is part of the international legal team representing Rappler journalist Maria Ressa in the Philippines, is positive about the response, and believes that the new US president Joe Biden is giving global leadership on this issue. He said: “It is always the few that need to lead. It’ll be interesting to see who does that.”

However, he pointed out that journalists have become less safe in the months since the report’s publication, with governments introducing laws during the pandemic that are being used aggressively against journalists.

Yeğinsu said the “recommendations are geared to really respond to instances where there’s a safety issue… so where the journalist is just looking for safe refuge”. This could cover a few options, such as a temporary stay or respite before a journalist returns home.

The report puts into context how these emergency visas could be incorporated into immigration systems such as those in the USA, Canada, the EU and the UK, at low cost and without the need for massive changes.

One encouraging sign came when former Canadian attorney-general Irwin Cotler said that “the Canadian government welcomes this report and is acting upon it”, while the UK foreign minister Lord Ahmad said his government “will take this particular report very seriously”. If they do not, the number of journalists killed and jailed while doing their jobs is likely to rise.

[This week, 20 UK media organisations issued an open letter calling for emergency visas for reporters in Afghanistan who have been targeted by the Taliban. Ruchi Kumar recently wrote for Index about the threats against journalists in Afghanistan from the Taliban.] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jul 2018 | News, Volume 46.01 Spring 2017

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1531732086773{background: #ffffff url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FinalBullshit-withBleed.jpg?id=101381) !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Manipulating news and discrediting the media are techniques that have been used for more than a century. Originally published in the spring 2017 issue The Big Squeeze, Index’s global reporting team brief the public on how to watch out for tricks and spot inaccurate coverage. Below, Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley introduces the special feature” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

FICTIONAL ANGLES, SPIN, propaganda and attempts to discredit the media, there’s nothing new there. Scroll back to World War I and you’ll find propaganda cartoons satirising both sides who were facing each other in the trenches, and trying to pump up public support for the war effort. If US President Donald Trump is worried about the “unbalanced” satirical approach he is receiving from the comedy show Saturday Night Live, he should know he is following in the footsteps of Napoleon who worried about James Gillray’s caricatures of him as very short, while the vertically challenged French President Nicolas Sarkozy feared the pen of Le Monde’s cartoonist Plantu.

When Trump cries “fake news” at coverage he doesn’t like, he is adopting the tactics of Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa. Cor-rea repeatedly called the media “his greatest enemy” and attacked journalists personally, to secure the media coverage he wanted.

As Piers Robinson, professor of political journalism at Sheffield University, said: “What we have with fake news, distorted information, manipulation communication or propaganda, whatever you want to call it, is nothing new.”

Our approach to it, and the online tools we now have, are newer however, meaning we now have new ways to dig out angles that are spun, include lies or only half the story.

But sadly while the internet has brought us easy access to multitudes of sources, and the ability to watch news globally, it also appears to make us lazier as we glide past hundreds of stories on Twitter, Facebook and the digital world. We rarely stop to analyse why one might be better researched than another, whose journalism might stand up or has the whiff of reality about it.

As hungry consumers of the news we need to dial up our scepticism. Disappointingly, research from Stanford University across 12 US states found millennials were not sceptical about news, and less likely to be able to differentiate between a strong news source and a weak one. The report’s authors were shocked at how unprepared students were in questioning an article’s “facts” or the likely bias of a website.

And, according to Pew Research, 66% of US Facebook users say they use it as a news source, with only around a quarter clicking through on a link to read the whole story. Hardly a basis for making any decision.

At the same time, we are seeing the rise of techniques to target particular demographics with political advertising that looks like journalism. We need to arm ourselves with tools to unpick this new world of information.

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Credit: Ben Jennings

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Turkey

A Picture Sparks a Thousand Stories

KAYA GENÇ dissects the use of shocking images and asks why the Turkish media didn’t check them

Two days after last year’s failed coup attempt in Turkey, one of the leading newspapers in the country, Sozcu, published an article with two shocking images purportedly showing anti-coup protesters cutting the throat of a soldier involved in the coup. “In the early hours of this morning the situation at the Bosphorus Bridge, which had been at the hands of coup plotters until last night, came to an end,” the piece read. “The soldiers handed over their guns and surrendered. Meanwhile, images of one of the soldiers whose throat was cut spread over social media like an avalanche, and those who saw the image of the dead soldier suffered shock,” it said.

These powerful images of a murdered uniformed youth proved influential for both sides of the political divide in Turkey: the ultra-conservative Akit newspaper was positive in its reporting of the lynching, celebrating the killing. The secularist OdaTV, meanwhile, made it clear that it was an appalling event and it was publishing the pictures as a means of protest.

Neither publication credited the images they had published in their extremely popular articles, which is unusual for a respectable publication. A careful reader could easily spot the lack of sources in the pieces too; there was no eyewitness account of the purported killing, nor was anyone interviewed about the event. In fact, the piece was written anonymously.

These signs suggested to the sceptical reader that the news probably came from someone who did not leave their desk to write the story, choosing instead to disseminate images they came across on social media and to not do their due diligence in terms of verifying the facts.

On 17 July, Istanbul’s medical jurisprudence announced that, among the 99 dead bodies delivered to the morgue in Istanbul, there was no beheaded person. The office of Istanbul’s chief prosecutor also denied the news, and it was declared that the news was fake.

A day later, Sozcu ran a lengthy commentary about how it prepared the article. Editors accepted that their article was based on rumours and images spread on social media. Numerous other websites had run the same news, their defence ran, so the responsibility for the fake news rested with all Turkish media. This made sense. Most of the pictures purportedly showing lynched soldiers were said to come from the Syrian civil war, though this too is unverifiable. Major newspapers used them, for different political purposes, to celebrate or condemn the treatment of putschist soldiers.

More worryingly, the story showed how false images can be used by both sides of Turkey’s political divide to manipulate public opinion: sometimes lies can serve both progressives and conservatives.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: China

A Case of Mistaken Philanthropy

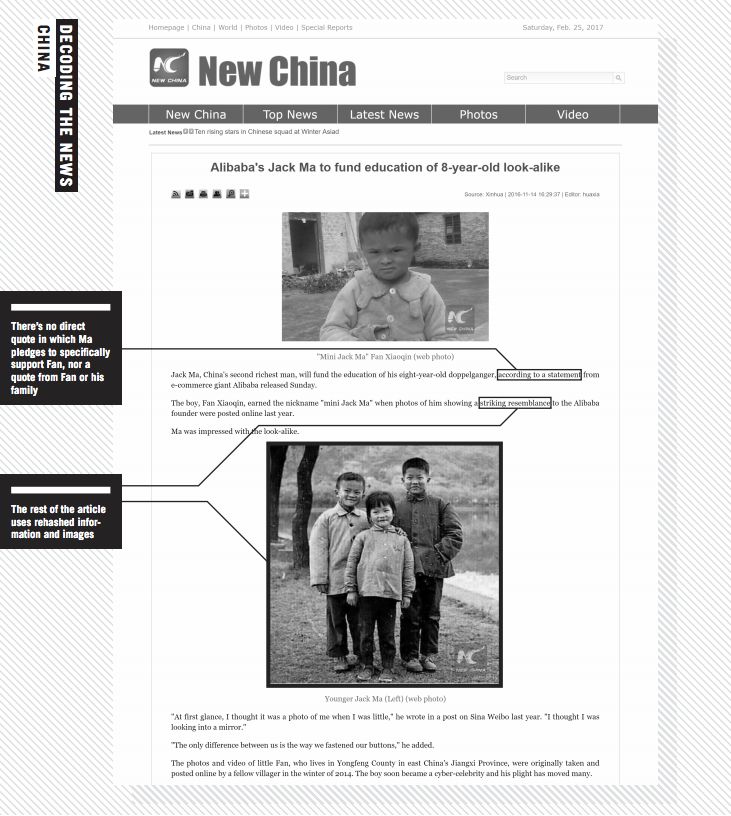

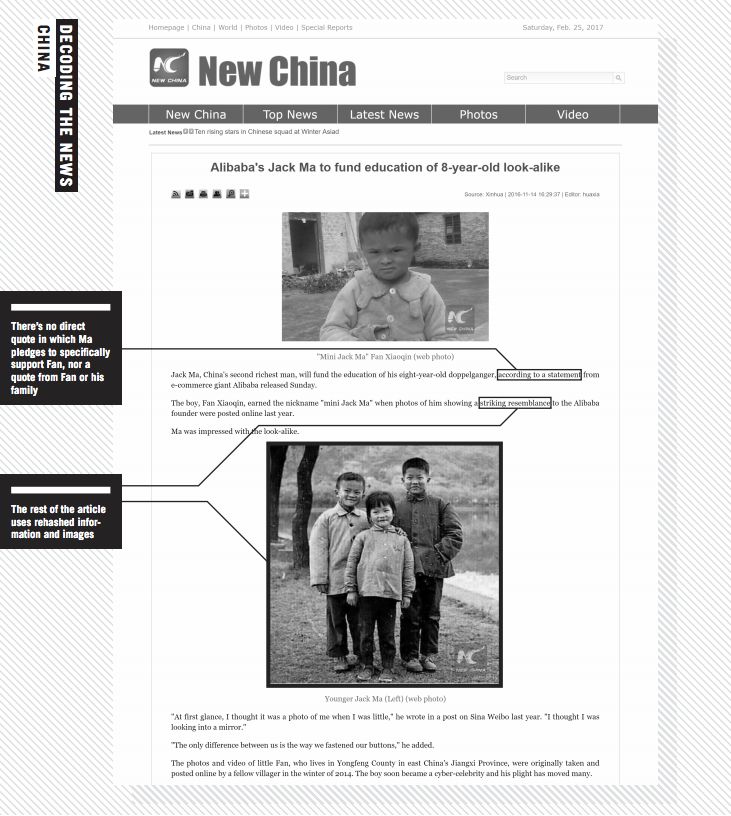

JEMIMAH STEINFELD writes on the story of Jack Ma’s doppelganger that went too far

Jack Ma is China’s version of Mark Zuckerberg. The founder and executive chairman of successful e-commerce sites under the Alibaba Group, he’s one of the wealthiest men in China. Articles about him and Alibaba are frequent. It’s within this context that an incorrect story on Ma was taken as verbatim and spread widely.

The story, published in November 2016 across multiple sites at the same time, alleged that Ma would fund the education of eight-year-old Fan Xiaoquin, nicknamed “mini Ma” because of an uncanny resemblance to Ma when he was of a similar age. Fan gained notoriety earlier that year because of this. Then, as people remarked on the resemblance, they also remarked on the boy’s unfavourable circumstances – he was incredibly poor and had ill parents. The story took a twist in November, when media, including mainstream media, reported that Ma had pledged to fund Fan’s education.

Hints that the story was untrue were obvious from the outset. While superficially supporting his lookalike sounds like a nice gesture, it’s a small one for such a wealthy man. People asked why he wouldn’t support more children of a similar background (Fan has a brother, in fact). One person wrote on Weibo: “If the child does not look like Ma, then his tragic life will continue.”

Despite the story drawing criticism along these lines, no one actually questioned the authenticity of the story itself. It wouldn’t have taken long to realise it was baseless. The most obvious sign was the omission of any quote from Ma or from Alibaba Group. Most publications that ran the story listed no quotes at all. One of the few that did was news website New China – sponsored by state-run news agency Xinhua. Even then the quotes did not directly pertain to Ma funding Fan. New China also provided no link to where the comments came from.

Copying the comments into a search engine takes you to the source though – an article on major Chinese news site Sina, which contains a statement from Alibaba. In this statement, Alibaba remark on the poor condition of Fan and say they intend to address education amongst China’s poor. But nowhere do they pledge to directly fund Fan. In fact, the very thing Ma was criticised for – only funding one child instead of many – is what this article pledges not to do.

It was not just the absence of any comments from Ma or his team that was suspicious; it was also the absence of any comments from Fan and his family. Media that ran the story had not confirmed its veracity with Ma or with Fan. Given that few linked to the original statement, it appeared that not many had looked at that either.

In fact, once past the initial claims about Ma funding Fan, most articles on it either end there or rehash information that was published from the initial story about Ma’s doppelganger. As for the images, no new ones were used. These final points alone wouldn’t indicate that the story was fabricated, but they do further highlight the dearth of new information, before getting into the inaccuracy of the story’s lead.

Still, the story continued to spread, until someone from Ma’s press team went on the record and denied the news, or lack thereof.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Mexico

Not a Laughing Matter

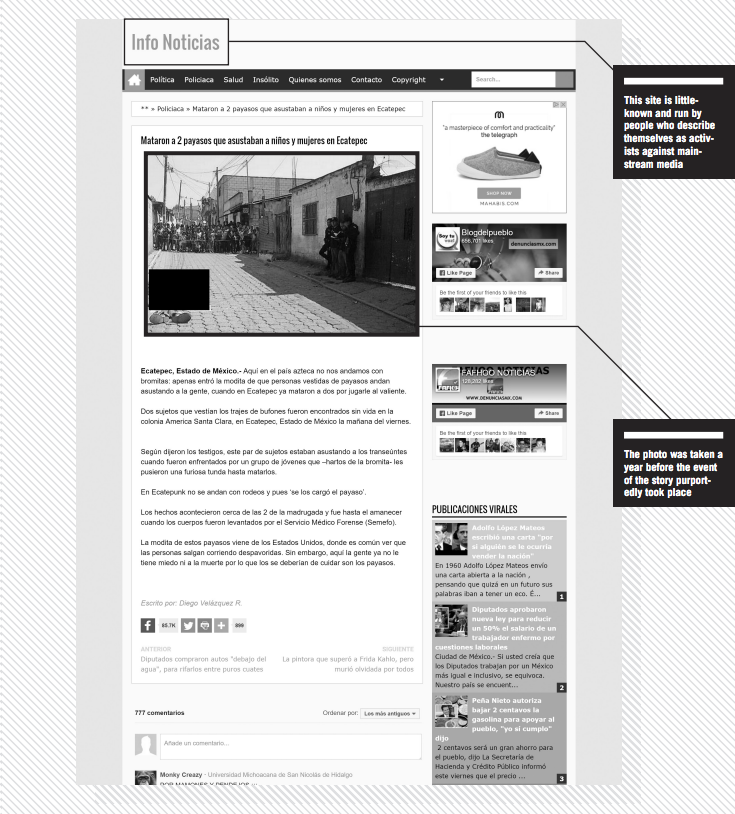

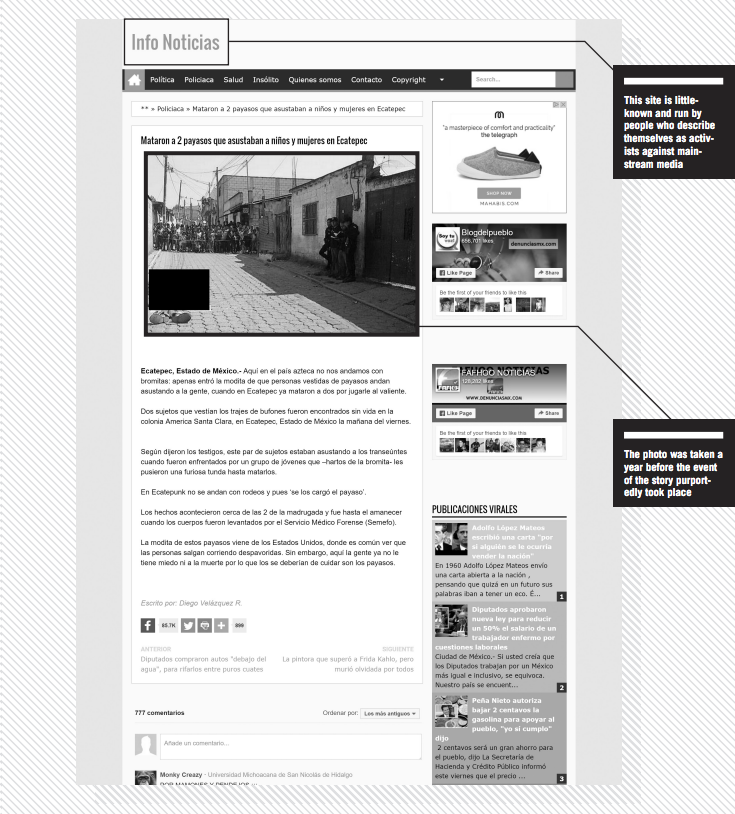

DUNCAN TUCKER digs out the clues that a story about clown killings in Mexico didn’t stand up

Disinformation thrives in times of public anxiety. Soon after a series of reports on sinister clowns scaring the public in the USA in 2016, a story appeared in the Mexican press about clowns being beaten to death.

At the height of the clown hysteria, the little-known Mexican news site DenunciasMX reported that a group of youths in Ecatepec, a gritty suburb of Mexico City, had beaten two clowns to death in retaliation for intimidating passers-by. The article featured a low-resolution image of the slain clowns on a run-down street, with a crowd of onlookers gathered behind police tape.

To the trained eye, there were several telltale signs that the news was not genuine.

While many readers do not take the time to investigate the source of stories that appear on their Facebook newsfeeds, a quick glance at DenunciasMX’s “Who are we?” page reveals that the site is co-run by social activists who are tired of being “tricked by the big media mafia”. Serious news sources rarely use such language, and the admission that stories are partially authored by activists rather than by professionally-trained journalists immediately raises questions about their veracity.

The initial report was widely shared on social media and quickly reproduced by other minor news sites but, tellingly, it was not reported in any of Mexico’s major newspapers – publications that are likely to have stricter criteria with regard to fact-checking.

Another sign that something was amiss was that the reports all used the vague phrase “according to witnesses”, yet none had any direct quotes from bystanders or the authorities

Yet another red flag was the fact that every news site used the same photograph, but the initial report did not provide attribution for the image. When in doubt, Google’s reverse image search is a useful tool for checking the veracity of news stories that rely on photographic evidence. Rightclicking on the photograph and selecting “Search Google for Image” enables users to sift through every site where the picture is featured and filter the results by date to find out where and when it first appeared online.

In this case, the results showed that the image of the dead clowns first appeared online in May 2015, more than a year before the story appeared in the Mexican press. It was originally credited to José Rosales, a reporter for the Guatemalan news site Prensa Libre. The accompanying story, also written by Rosales, stated that the two clowns were shot dead in the Guatemalan town of Chimaltenango.

While most of the fake Mexican reports did not have bylines and contained very little detail, Rosales’s report was much more specific, revealing the names, ages and origins of the victims, as well as the number of shell casings found at the crime scene. Instead of rehashing rumours or speculating why the clowns were targeted, the report simply stated that police were searching for the killers and were working to determine the motive.

As this case demonstrates, with a degree of scrutiny and the use of freely available tools, it is often easy to differentiate between genuine news and irresponsible clickbait.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Eritrea

Not North Korea

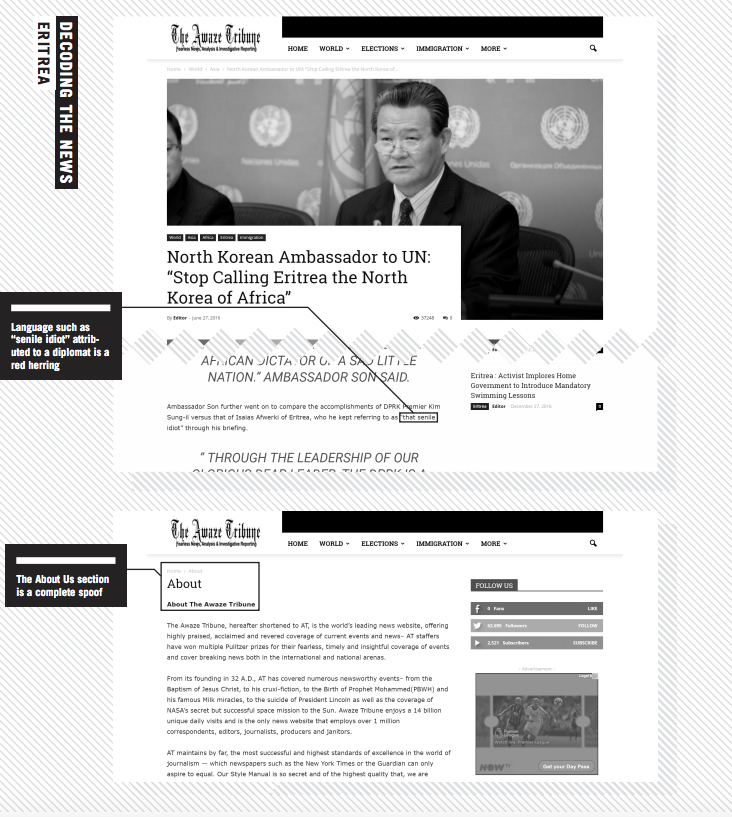

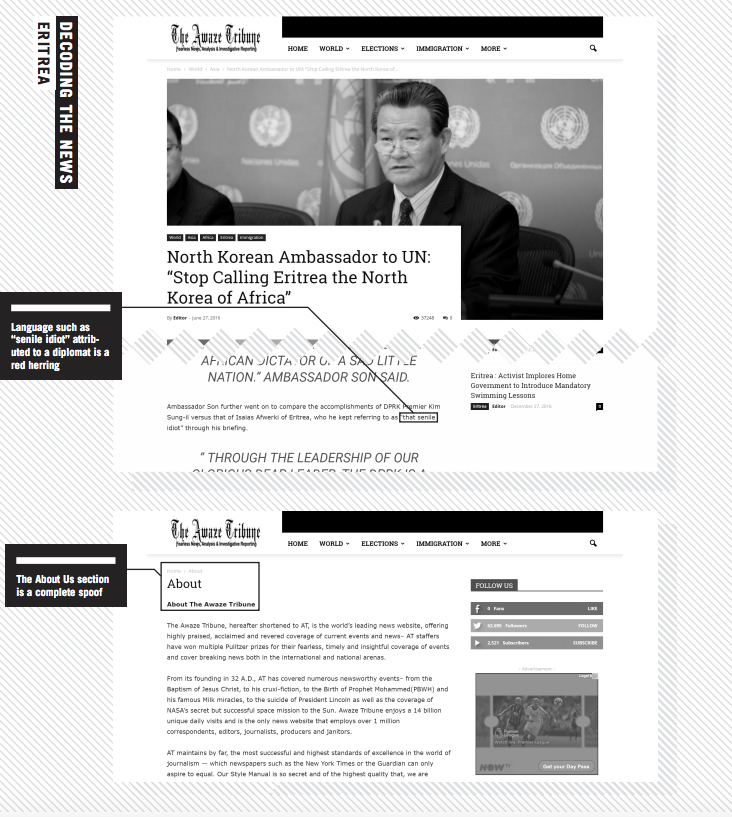

ABRAHAM T ZERE dissects the moment that Eritreans mistook saucy satire for real news

In recent years, the international media have dubbed Eritrea the “North Korea of Africa”, due to their striking similarities as closed, repressive states that are blocked to international media. But when a satirical website run by exiled Eritrean journalists cleverly manipulated the simile, the site stoked a social media buzz among the Eritrean diaspora.

Awaze Tribune launched last June with three news stories, including “North Korean ambassador to UN: ‘Stop calling Eritrea the North Korea of Africa’.”

The story reported that the North Korean ambassador, Sin Son-ho, had complained it was insulting for his advanced, prosperous, nuclear-armed nation to be compared to Eritrea, with its “senile idiot leader” who “hasn’t even been able to complete the Adi Halo dam”.

With apparent little concern over its authenticity, Eritreans in the diaspora began widely sharing the news story, sparking a flurry of discussion on social media and quickly accumulating 36,600 hits.

The opposition camp shared it widely to underline the dismal incompetence of the Eritrean government. The pro-government camp countered by alleging that Ethiopia must have been involved behind the scenes.

The satirical nature of the website should have seemed obvious. The name of the site begins with “Awaze”, a hot sauce common in Eritrean and Ethiopian cuisines. If readers were not alerted by the name, there were plenty of other pointers. For example, on the same day, two other “news” articles were posted: “Eritrea and South Sudan sign agreement to set an imaginary airline” and “Brexit vote signals Eritrea to go ahead with its long-planned referendum”.

Although the website used the correct name and picture of the North Korean ambassador to the UN, his use of “senile idiot” and other equally inappropriate phrases should have betrayed the gag.

Recently, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has been spending time at Adi Halo, a dam construction site about an hour’s drive from the capital, and he has opened a temporary office there. While this is widely known among Eritreans, it has not been covered internationally, so the fact that the story mentioned Adi Halo should also have raised questions of its authenticity with Eritreans. Instead, some readers were impressed by how closely the North Korean ambassador appeared to be following the development.

The website launched with no news items attributed to anyone other than “Editor”, and even a cursory inspection should have revealed it was bogus. The About Us section is a clear joke, saying lines such as the site being founded in 32AD.

Satire is uncommon in Eritrea and most reports are taken seriously. So when a satirical story from Kenya claimed that Eritrea had declared polygamy mandatory, demanding that men have two wives, Eritrea’s minister of information felt compelled to reply.

In recent years, Eritrea’s tightly closed system has, not surprisingly, led people to be far less critical of news than they should be. This and the widely felt abhorrence of the regime makes Eritrean online platforms ready consumers of such satirical news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: South Africa

And That’s a Cut

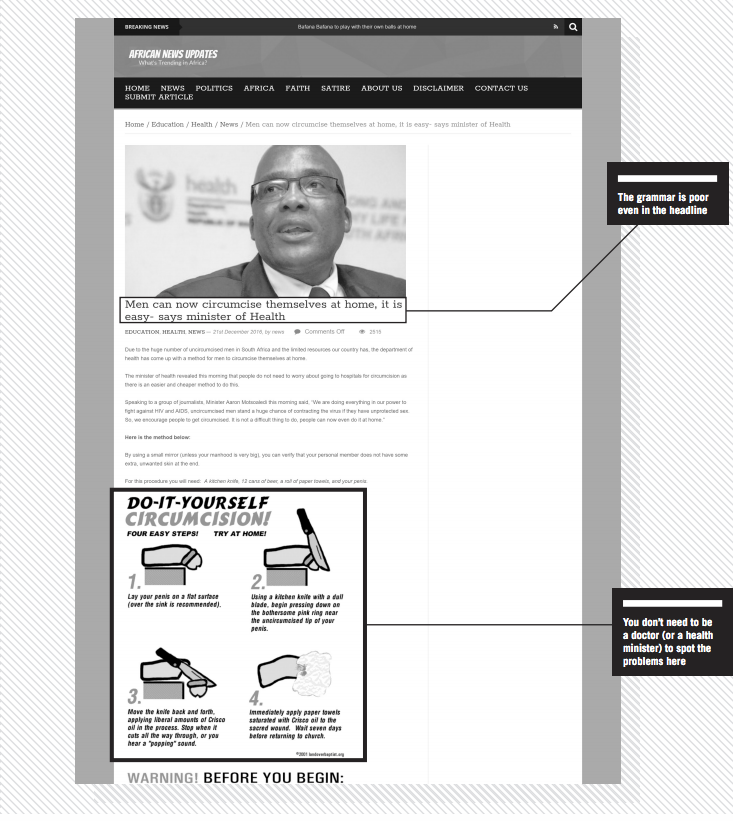

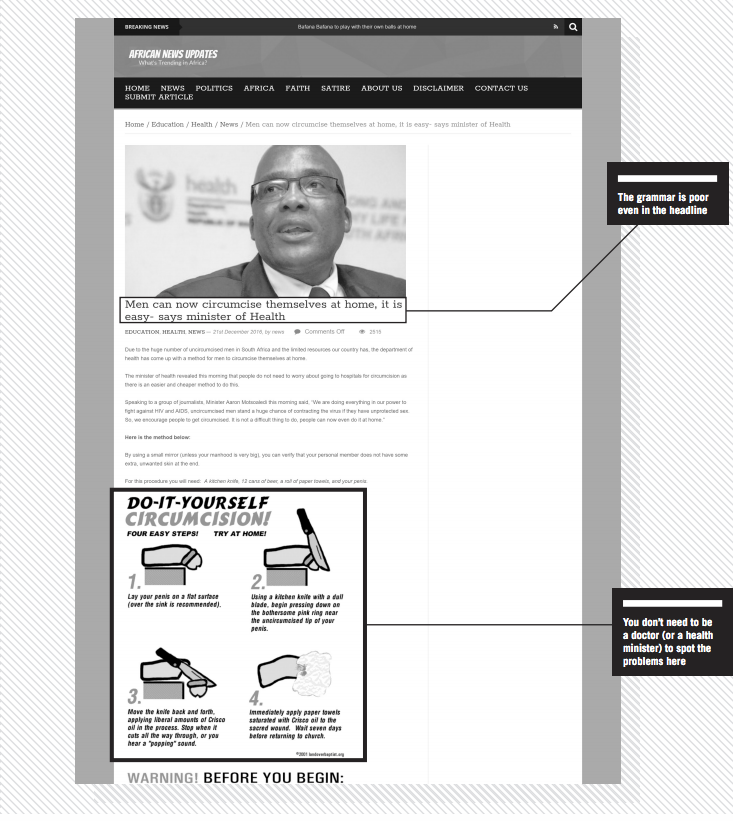

Journalist NATASHA JOSEPH spots the signs of fiction in a story about circumcision

The smartest tall tales contain at least a grain of truth. If they’re too outlandish, all but the most gullible reader will see through the deceit. Celebrity death stories are a good example. In South Africa, dodgy “news” sites routinely kill off local luminaries like Desmond Tutu. The cleric is 85 years old and has battled ill health for years, so fake reports about his death are widely circulated.

This “grain of truth” rule lies at the heart of why the following headline was perhaps believed. The headline was “Men can now circumcise themselves at home, it is easy – says minister of health”. Circumcision is a common practice among a number of African cultural groups. Medical circumcision is also on the rise. So it makes sense that South Africa’s minister of health would be publicly discussing the issue of circumcision.

The country has also recently unveiled “DIY HIV testing kits” that allow people to check for HIV in their own homes. This is common knowledge, so casual or less canny readers might conflate the two procedures.

The reality is that most of us are casual readers, snacking quickly on short pieces and not having the time to engage fully with stories. New levels of engagement are required in a world heaving with information.

The most important step you can take in navigating this terrible new world is to adopt a healthy scepticism towards everything. Yes, it sounds exhausting, but the best journalists will tell you that it saves a lot of time to approach information with caution. My scepticism manifests as what I call my “bullshit detector”. So how did my detector react to the “DIY circumcision” story?

It started ringing instantly thanks to the poor grammar evident in the headline and the body of the text. Most proper news websites still employ sub editors, so lousy spelling and grammar are early warning signals that you’re dealing with a suspicious site.

The next thing to check is the sourcing: where did the minister make these comments? To whom? All this article tells us is that he was speaking “in Johannesburg”. The dearth of detail should signal to tread with caution. If you’ve got the time, you might also Google some key search terms and see if anyone else reported on these alleged statements. Also, is there a journalist’s name on the article? This one was credited to “author”, which suggests that no real journalist was involved in production.

The article is accompanied by some graphic illustrations of a “DIY circumcision”. If you can stomach it, study the pictures. They’ll confirm what I immediately suspected upon reading the headline: this is a rather grisly example of false “news”.

Finally, make sure you take a good look at the website that runs such an article. This one appeared on African News Updates.

That’s a solid name for a news website, but two warning bells rang for me: the first bell was clanged by other articles, which ranged from the truth (with a sensational bent) to the utterly ridiculous. The second bell rang out of control when I spotted a tab marked “satire” along the top. Click on it and there’s a rant ridiculing anyone who takes the site seriously. Like I needed any excuse to exit the site and go in search of real news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: How To

Get the Tricks of the Trade

Veteran journalist RAYMOND JOSEPH explains how a handy new tool from South Africa can teach you core journalism skills to help you get to the truth

It’s been more than 20 years since leading US journalist and journalism school teacher Melvin Mencher released his Reporter’s Checklist and Notebook, a brilliant and simple tool that for years helped journalists in training.

Taking cues from Mencher’s, there’s now a new kid on the block designed for the digital age. Pocket Reporter is a free app that leads people through the newsgathering process – and it’s making waves in South Africa, where it was launched in late 2016.

Mencher’s consisted of a standard spiral-bound reporter’s notebook, but also included tips and hints for young reporters and templates for a variety of stories, including a crime, a fire and a car crash. These listed the questions a journalist needed to ask.

Cape Town journalist Kanthan Pillay was introduced to Mencher’s notebook when he spent a few months at the Harvard Business School and the Nieman Foundation in the USA. Pillay, who was involved in training young reporters at his newspaper, was inspired by it. Back in South Africa, he developed a website called Virtual Reporter.

“Mencher’s notebook got me thinking about what we could do with it in South Africa,” said Pillay. “I believed then that the next generation of reporters would not carry notebooks but would work online.”

Picking up where Pillay left off, Pocket Reporter places the tips of Virtual Reporter into your mobile phone to help you uncover the information that the best journalists would dig out. Cape Town-based Code for South Africa re-engineered it in partnership with the Association of Independent Publishers, which represents independent community media.

It quickly gained traction among AIP’s members. Their editors don’t always have the time to brief reporters – who might be inexperienced journalists or untrained volunteers – before they go out on stories.

This latest iteration of the tool, in an age when any smartphone user can be a reporter, is aimed at more than just journalists. Ordinary people without journalism training often find themselves on the frontline of breaking news, not knowing what questions to ask or what to look out for.

Code4SA recently wrote code that makes it possible to translate the content into other languages besides English. Versions in Xhosa, one of South Africa’s 11 national languages, and Portuguese are about to go live. They are also currently working on Afrikaans and Zulu translations, while people elsewhere are working on French and Spanish translations.

“We made the initial investment in developing Pocket Reporter and it has shown real world value. It is really gratifying to see how the project is now becoming community-driven,” said Code4SA head Adi Eyal.

Editor Wara Fana, who publishes his Xhosa community paper Skawara News in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, said: “I am helping a collective in a remote area to launch their own publication, and Pocket Reporter has been invaluable in training them to report news accurately.” His own journalists were using the tool and he said it had helped improve the quality of their reporting.

Cape Peninsula University of Technology journalism department lecturer Charles King is planning to incorporate Pocket Reporter into his curriculum for the news writing and online-media courses he teaches.

“What’s also of interest to me is that there will soon be Afrikaans and Xhosa versions of the app, the first languages of many of our students,” he said.

Once it has been downloaded from the Google Play store, the app offers a variety of story templates, covering accidents, fires, crimes, disasters, obituaries and protests.

The tool takes you through a series of questions to ensure you gather the correct information you need in an interview.

The information is typed into a box below each question. Once you have everything you need, you have the option of emailing the information to yourself or sending it directly to your editor or anyone else who might want it.

Your stories remain private, unless you choose to share them. Once you have emailed the story, you can delete it from your phone, leaving no trace of it.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

This article originally appeared in the spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Kaya Genç is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine based in Istanbul, Turkey

Jemimah Steinfeld is deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Duncan Tucker is a regular correspondent for Index on Censorship magazine from Mexico

Journalist Abraham T Zere is originally from Eritrea and now lives in the USA. He is executive director of PEN Eritrea

Natasha Joseph is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is also Africa education, science and technology editor at The Conversation

Raymond Joseph is former editor of Big Issue South Africa and regional editor of South Africa’s Sunday Times. He is based in Cape Town and tweets @rayjoe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533808″][vc_custom_heading text=”There’s nothing new about fake news” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533808|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Andrei Aliaksandrau takes a look at fake news in Belarus[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532452″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fake news: The global silencer” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532452|||”][vc_column_text]April 2018

Caroline Lees examines fake news being used to imprison journalists [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229808536482″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taking the bait” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229808536482|||”][vc_column_text]April 2017

Richard Sambrook discusses the pressures click-bait is putting on journalism[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88802″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]