4 Mar 2014 | Africa, News and features, Uganda

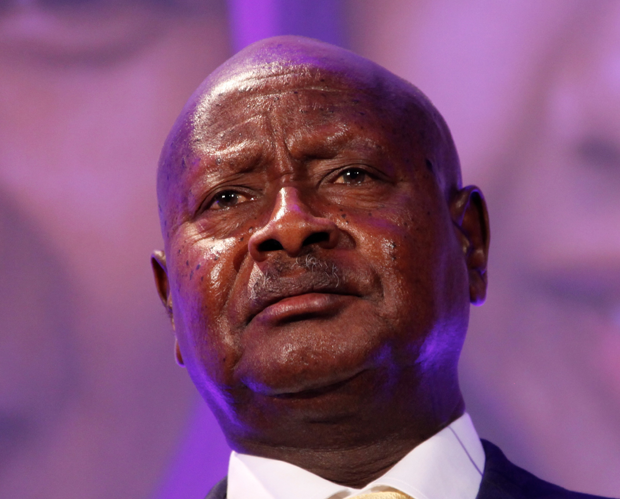

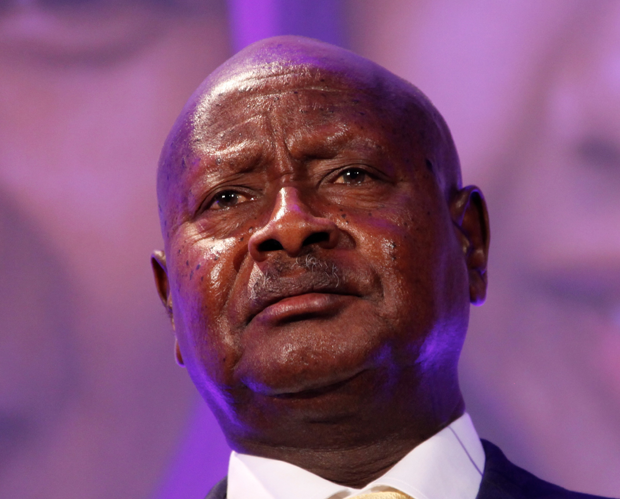

Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni (Photo: Wikipedia)

President Yoweri Museveni signed Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality bill into law on 24 February, and the fallout has already started. The World Bank has cancelled a $90 million loan to the country, European Union countries are threatening to withdraw aid, and the United States is reviewing its cooperation with Uganda. President Museveni has hit back, saying Uganda would raise its own money to fund its development projects. The US, which was the first voice its discontent, was told off: “Our relationship with the US was not based on homosexuality.” David Bahati, the MP who introduced the bill, said in an interview that the west is imposing social imperialism on Uganda, a thing they are not ready to accept.

“I will work with the Russians,” Museveni said.

So the president feels that even without the west, Uganda has development partners that it can still rely on. Considering he was not supportive of the so-called Bahati bill in its initial stages, Museveni’s last-minute change of heart is baffling.

The law stipulates that punishment for homosexuals will be a life jail sentence, while those who “attempt” to engage in homosexual acts face seven years in prison. The law also targets journalists and others seen to participate in “production, procuring, marketing, broadcasting, disseminating, publishing of pornographic materials for purposes of promoting homosexuality”. It even attempts to reach beyond the country’s borders, implong that Uganda will have to ask countries where gay Ugandans live to extradite them so that they can face the law.

Public opinion goes both ways. Many are happy that the president is standing firm against “the west” and the perceived scheme of promoting homosexuality in Uganda and Africa at large. Others claim that the president signed this law to achieve cheap popularity with the 2016 elections around the corner. It is also claimed that President Museveni is just playing his usual political games. When the anti-homosexuality bill was passed by parliament early this year, one of the president’s legal brains, Fox Odoi, publicly stated that if the president ever assents to this law, he would challenge it in court.

Odoi has now teamed up with Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda to take the case to the constitutional court. It is alleged that this was Museveni’s game plan: sign the law, annoy the west and appease the locals, and then have his henchmen challenge this law in court and make sure it remains there forever. In this case, the west will soften their stance towards Museveni, and the locals will be told to be patient and leave the legal process to take its course. In that case, he will have killed two birds with one stone, and would go for the 2016 elections with both the west and the locals in his pockets.

Civil society has also been critical, not because the anti-homosexuality law is unnecessary per se, but they have questioned whether homosexuality is the biggest problem Uganda faces today, and warrants such urgency. With high youth unemployment, squalid conditions in health facilities and theft of public funds in government institutions, they believe priorities should lie somewhere else other than “fixing” homosexuality.

“The timing for the assenting to this law by the president is meant to divert the country’s attention from the discussion on the deployment of Ugandan forces in South Sudan and our mandate there. This law is very diversionary, and it is unfortunate that Ugandans have swallowed the president’s bait,” said Godber Tumushabe, a renowned civil society activist.

Opposition leader Kizza Besigye has criticised the new law, saying that homosexuality was not “foreign” and that the issue was being used to divert attention from domestic problems. “Homosexuality is as Ugandan as any other behaviour, it has nothing to do with the foreigners,” said Besigye. He accused the government of having “ulterior motives” and using the issue to divert attention from other issues, including Uganda’s military backing of neighbouring South Sudan’s government against rebel forces.

Sweden’s Finance Minister Anders Borg, who visited the country a day after the signing of the law, said it “presents an economic risk for Uganda”.

But Besigye accused them of double standards, saying that their cutting of aid over gay rights alone was “misguided”:

”They should have cut aid a long time ago because of more fundamental rights, our rights have been violated with impunity and they kept silent,” he said.

This article was posted on March 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Jan 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features, United Nations

(Image: Pseudopixels/Shutterstock)

If you live in Cuba, Iran or Sudan, and are using the increasingly popular online education tool Coursera, you are likely encounter some access difficulties from this week onwards. Coursera has been included in the US export sanctions regime.

The changes have only come about now, as Coursera believed they and other MOOCs — Massive Open Online Courses — didn’t fall under American export bans to the countries. However, as the company explained in a statement on their official blog: “We recently received information that has led to the understanding that the services offered on Coursera are not in compliance with the law as it stands.”

Coursera, in partnership with over 100 universities and organisations, from Yale to the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology to the Word Bank, offers online courses in everything from Economics and Finance to Music, Film and Audio — free of charge. Over four million students across the world are currently enrolled.

“We envision a future where everyone has access to a world-class education that has so far been available to a select few. We aim to empower people with education that will improve their lives, the lives of their families, and the communities they live in,” they say.

But this noble aim is now being derailed by US economic sanctions policy. People in Cuba, Iran and Sudan will be able to browse the website, but existing students won’t be able to log onto their course pages, and new students won’t be allowed to sign up. Syria was initially included on the list, but was later removed under an exception allowing services that support NGO efforts.

Amid clear-cut cases of censorship, peaceful protesters being attacked and journalists thrown in jail, it is easy forget that access — or rather lack of it — also constitutes a threat to freedom of expression. Lack of access to freedom of expression leads to people being denied an equal voice, influence and active and meaningful participation in political processes and their wider society.

In these connected times, it can be a simple as being denied reliable internet access. Coursera is trying to tackle this problem. They “started building up a mobile-devices team so that students in emerging markets — who may not have round-the-clock access to computers with internet connectivity — can still get some of their coursework done via smartphones or tablets,” reported Forbes.

But this won’t be of much help to students affected by the sanctions, as their access is being restricted not by technological shortcomings, but by misguided policy. Education plays a vital part in helping provide people with the tools to speak out, play an active part in their society and challenge the powers that be. Taking an education opportunity away from people in Cuba, Iran and Sudan is another blow to freedom of expression in countries with already poor records in this particular field.

Furthermore, these sanctions are in part enforced in a bid to stand up for human rights. This loses some of its power, when the people on the ground in the sanctioned countries are being denied a chance to further educate themselves, gaining knowledge that could help them be their own agents of change and stand up for their own rights.

Ironically, this counterproductive move comes not long after a Sudanese civil society group called for a change to US technology sanction.

“We want to be clear that this is not an appeal to lift all sanctions from the Sudanese regime that continues to commit human rights atrocities. This is an appeal to empower Sudanese citizens through improved access to ICTs so that they can be more proactive on issues linked to democratic transformation, humanitarian assistance and technology education — an appeal to make the sanctions smarter,” said campaign coordinator Mohammed Hashim Kambal.

Digital freedom campaigners from around the world have also spoken against the US position

Coursera says they are working to “reinstate site access” to the users affects, adding that: “The Department of State and Coursera are aligned in our goals and we are working tirelessly to ensure that blockage is not permanent.”

For now, students in Iran, Cuba and Sudan could access Coursera through a VPN network.

Hopefully this barrier to freedom of expression in countries where it is sorely needed, will soon be reversed.

This article was posted on 31 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Jan 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

At its core, freedom of religion or belief requires freedom of expression. Both fundamental rights are protected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, yet nearly half of all countries penalize blasphemy, apostasy or defamation of religion. In 13 countries, atheists can be put to death for their lack of belief.

The U.S. State Department names and shames eight “Countries of Particular Concern” that severely violate religious freedom rights within their borders. These countries not only suppress religious expression, they systematically torture and detain people who cross political and social red lines around faith. The worst of the worst are:

1. Burma

Burma’s population is 90 percent Theravada Buddhist, a faith the government embraces and promotes over Christianity, Islam and Hinduism. Minority populations that adhere to these and other faiths are denied building permits, banned from proselytizing and pressured to convert to the majority faith. Religious groups must register with the government, and Burmese citizens must list their faith on official documents. Burma’s constitution provides for limited religious freedom, but individual laws and government officials actively restrict it. Most at risk in Burma are Rohingya Muslims, 240 of whom were killed this year in clashes with Buddhist mobs. Burma has refused to grant citizenship to 800,000 Rohingya, 240,000 of whom have fled their homes in recent clashes.

2. China

The ruling Chinese Communist Party is officially an atheist organisation. China’s constitution provides for freedom of religious belief, but the government actively restricts any religious expression that could potentially undermine its authority. Only five religious groups — Buddhists, Taoists, Muslims, Catholics and Protestants — can register with the government and legally hold services. Adherents of unregistered faiths and folk religions often worship illegally and in secret. Uighur Muslims, Tibetan Buddhists and Falun Gong practitioners have faced particularly severe repression in recent years, including forced conversion, torture and imprisonment.

3. Eritrea

The Eritrean government only recognizes four religious groups: the Eritrean Orthodox Church, Sunni Islam, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Eritrea. These groups enjoy limited religious freedom while adherents of other faiths face harassment and imprisonment. Religious persecution in Eritrea is generally driven by government rather than social concerns. Jehovah’s Witnesses and other conscientious objectors who refuse to enroll in compulsory military training are subject to physical abuse, detention and hard labour. People of non-recognized religions are barred from congregating in disused houses of worship and have trouble obtaining passports or visas to exit the country.

4. Iran

Iran’s constitution offers some religious freedom rights for recognized sects of Islam along with Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians. Baha’is, who the government considers apostates and labels a “political sect,” are excluded from these limited protections and are systematically discriminated against through gozinesh provisions, which limit their access to employment, education and housing. Evangelical Christians and other faith groups face persecution for violating bans on proselytizing. Religious minorities have been charged in recent years and imprisoned in harsh conditions for committing “enmity against God” and spreading “anti-Islamic propaganda.” Government-controlled media regularly attack Baha’is, Jews and other minority faiths to amplify social hostilities against them.

5. North Korea

North Korea’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but this right is far from upheld. The state is officially atheist. Author John Sweeney says the country is “seized by a political religion” and that it considers established religious traditions a threat to state unity and control. North Korea allow for government-sponsored Christian and Buddhist religious organizations to operate and build houses of worship, but political analysts suspect this “concession” is for the sake of external propaganda. A Christian group says it dropped 50,000 Bibles over North Korea over the past year. If caught with one, citizens face imprisonment, torture or even death. Given the government’s extreme control over the flow of reliable information, it is difficult to determine the true extent of religious persecution in North Korea.

6. Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s constitution is not a standalone document. It is comprised of the Quran and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, which do not include religious freedom guarantees as spelled out in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In Saudi, it is illegal to publicly practice any faith other than the state’s official religion Sunni Islam. Members of other faiths can worship privately, but non-Muslim houses of worship may not be built. The Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, otherwise known as Saudi’s morality or religious police, enforce Shariah law on the streets. Apostasy and blasphemy against Sunni Islam can be punished by death, as several high-profile Twitter cases have reminded global media in recent years.

7. Sudan

Sudan’s interim constitution partially protects religious freedom but restricts apostasy, blasphemy and defamation of Islam. Muslim women are also prevented from marrying non-Muslim men. The country’s vaguely worded apostasy law discourages proselytizing of non-Muslim faiths. Christian South Sudanese living in Sudan are subject to harassment and intimidation by government agents and society at large, but untangling the religious and ethnic motivations for this persecution can be difficult. Muslims generally enjoy social, legal and economic privileges denied to the Christian minority population. Government authorities have reportedly destroyed churches in recent years, and Christian groups have reportedly been subject to disproportionate taxes and delays in building new houses of worship. Read more about Sudan’s crackdown on Christians.

8. Uzbekistan

Proselytizing is prohibited in Uzbekistan, and religious groups must undergo a burdensome registration process with the government to enjoy what limited religious freedom is permitted in the country. More than 2,000 religious groups have registered with the government, the vast majority of which are Muslim but also include Jewish, Catholic and other Christian communities. Registered and unregistered groups are sometimes subject to raids, during which holy books have been destroyed. Individuals and groups deemed “extremist,” often for national security concerns rather than specific aspects of their faith, are imprisoned under harsh conditions and tortured, sometimes to death.

18 Nov 2013 | Magazine, News and features

It is an astonishing fact that Zimbabwe, after 20 years of a rule that has starved libraries and schools of books, is full of people who yearn for books, who see them as a key to a better life, and whose attitude is similar to that of people in Europe and the USA up to 50 years ago who read because they agreed with Carlyle’s dictum ‘the real education is a good library’ — and aspired to be educated.

There are libraries and libraries. Some I am involved with would not be recognised as such in more fortunate parts of the world. A certain trust sends boxes of books out to villages which might seem to the illinformed no more than clusters of poor thatched mud huts, but in them may be retired teachers, teachers on holiday, people with three or four years of education who yearn for better. These villages may have no electricity, telephone, running water, but they beg for books from every visitor. Perhaps a hut may be set aside for books, with a couple of shelves in it, or shelves or a trestle may be put under a tree. In a bush village far from any big town, or even a little one, such a trestle with 40 books on it has transformed the life of the area. Instantly study groups appeared, literacy classes — people who can read teaching those who can’t — civic classes and groups of aspirant writers.

A letter from there reads: ‘People cannot live without water. Books are our water and we drink from this spring.’

An enterprising council official in Bulawayo sends out books by donkey car — ‘our travelling library’ — to places where ordinary transport cannot go, because there are no roads, or roads that succumb to dust or mud.

A friend of mine, known to be involved with organisations that supply books, was approached .by two youths in a bush village near Lake Kariba who said, ‘We have built a library, now please give us the books.’

The library was a shelf in a little lean-to of grass and poles, but the books would never succumb to white ants or the book-devouring fish-moth, because they would always be out on loan.

A survey was made in the villages and it turned out that what these book-starved people yearn for are romances, detective stories, poetry, adventures, biography, novels of all kinds, short stories.

Exactly what a survey in this country would reveal — that is, among people who still read.

One problem is that these people do not know what is available that they might like if they tried. The Mayor of Casterbridge was a school set book one year and was read by the adults, and so people ask for books by Hardy.

The most popular book everywhere is George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Another that has queues waiting for it is World Tales by Idries Shah, and it is not only the tales themselves, but the scholarly footnotes attached to them which people enjoy. They say of a story, perhaps from the Sudan or the USA, ‘But we have a story just like that.’

One problem is that people, hearing of this book hunger, at once offer to donate their cast-off books. These are not always suitable. Donations would be better. Book Aid International, based in London, sends books out to book-starved countries.

This article was originally published in Index on Censorship magazine, March 1999.

Click here to subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine, or download the app here