Laos: Crony scheme in control of press and civil society

The Laotian president, Choummaly Sayasone, made a five day official visit to France in October 2013 — the first such visit in 60 years. (Photo: Serge Mouraret / Demotix)

When travellers and writers talk about Laos, they mention how peaceful it is, and how Buddhist. The people, says Lonely Planet, are some of the most chilled out in the world. People forget, as they rarely do with Vietnam or China, that it is still a communist state.

The Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP) has absolute control over the press and civil society. Professor Martin Stuart-Fox, a Laos expert with the University of Queensland, has written widely on the country’s history and government and has said that the party is little more than a crony scheme, with many of those in power now descended from the old Lao aristocracy. It is necessary to have a powerful patron, almost always in the party or closely connected to it, for success. Information is difficult to get hold of and even local journalists, who often have close ties to the government, complain publicly, if respectfully, about the impenetrability of government departments.

Freedom House writes: “Press freedom in Laos remains highly restricted. Despite advances in telecommunications infrastructure, government control of all print and broadcast news prevents the development of a vibrant, independent press.”

These media restrictions are part of a wider pattern of suppression of information, lack of transparency in business dealings, prevention of protests and cultural and religious oversight by the government and party.

However the most noticeable event of the past 18 months has been the disappearance of Sombath Somphone. At the end of 2012 the Lao development expert went missing and many of his colleagues quietly believe the government may be responsible. Little but the bare facts have been written in the local, state-owned press.

Sombath was, according to reports, well respected by both the local and international communities and hardly an anti-government firebrand. He did, however, jointly give a presentation in late 2012 to the ASEAN-Europe People‘s Forum held in Vientiane with the United Nations Development Program. A western aid source told Index on Censorship: “In my opinion — one shared by many others as well –Sombath’s statement at the AEPF was the last straw for the government. He was particularly concerned with forced resettlement, directly linked to government land grabs to provide natural resources to Chinese companies [that are] full of bribes.” The source says since Sombath disappeared any attempts at criticism of government policy, either by the press or organisations “have taken a quantum leap backwards and are currently frozen”.

The World Trade Organisation accession of last year appears not to have much of an effect in promoting a freer or transparent climate. Though the global trade body did make the right noises little concrete action was taken.

This is in contrast to Vietnam’s 2007 WTO accession. In the lead up, the Vietnamese government made public attempts at allowing more freedom of press and speech and open criticism of government policies. Once it became the 150th member crackdowns began again. A small measure of transparency in regards to the business climate has been seemingly taken in Laos.

The LPRP has been in power since 1975. Agricultural reforms began in 1978 and economic reform in 1986, known as the New Economic Mechanism, which began its transition to a more market-based economy. Vietnam instituted its own doi moi, or renovation, policy the same year.

Laos has, in the past 15 years, pursued a policy of economic growth and regional and global integration with an eye toward world affairs. Joining ASEAN in 1997 was a step forward for the small nation, though the spillover Asian financial crisis engendered a certain skepticism among leaders of the manifold benefits of globalisation.

Many smaller nations racing towards development, especially those with sometimes problematic political systems, usually host an event that is as something of a “coming out party”. Vientiane’s hosting of the 2009 Southeast Asia Games was Laos’. Longtime Asia journalist Bertil Lintner pointed out in the Yale Global Review, that though the SEA Games may not have been compelling for much of the globe they are an important regional sporting competition. Chinese and Vietnamese donors and investment built much of the needed infrastructure, such as stadiums.

Despite the rapid development and a “strong” growth outlook for 2013 – 2014, according to Euromonitor, the country still struggles under Least Developed Nation status and poverty rates are high outside the cities while access to services remains low, as do literacy rates.

Unemployment is officially at 2.6 percent of the population, but it is widely believed to be far higher and according to market research and intelligence firm Euromonitor there will be twice as many job entrants as positions for them to fill. Labour export is favoured by the government to partially solve the issue and earn currency. The poverty rate has dropped in recent years and the government’s plan has been to halve it by 2015.

Freedom of the press?

“The Ministry of Information and Culture controls all media in Laos. There is no freedom of the press and no legal protection for Lao journalists who fail to reflect the party line. Most Lao journalists are actually party members attached to the MI,” Stuart-Fox wrote for Freedom House in 2012.

“Laos is the region’s black hole for news…. Because there is no functioning independent media, there are few overt press freedom violations,” Shawn Crispin of the Committee to Protect Journalists told Index. “No local reporting is allowed whatsoever on government corruption, official abuses or factional divisions inside the ruling communist Lao Revolutionary People’s Party. These are all pervasive in Laos, but you’d never know it reading local papers on watching local TV.”

Laos enshrines freedom of speech in its constitution, written in 1991, while ensuring harsh penalties in its penal code that can easily be applied to journalists, or bloggers — though bloggers are few and generally timid. Slandering the state, distorting party and state policies, inciting disorder or propagating information or opinions that weaken the state can all be prosecuted. The vague wording means many things can, if deemed necessary, fall under this ambit.

The English language Vientiane Times largely functions as a platform for photographs of handshakes, ribbon cuttings and deeply earnest affirmations of the great friendship between Laos and whichever national delegation dropped off in the capital on its Southeast Asia tour. It is essentially a showcase organ for what the government wishes foreigners to see, and understand, about modern Laos however its often rather old-fashioned, orthodox rhetoric and complete dearth of anything interesting do not ensure an avid readership.

“The Vietnamese media is much more open, skilled, and sophisticated than the Lao media. And the Lao media are dominated by self-censorship,” a senior Lao source from Radio Free Asia said in an email to Index. “Within limits some publications in Vietnam do try to do investigative journalism. You simply won’t find that in Laos.” The source pointed out that a query on the large scale illegal logging with logs going to Vietnam might not yield much past government authority saying that the government tries to protect the environment.

The 2008 media law is theoretically more friendly to the media and transparency — journalists are guaranteed the right to seek and publish information and to access to public records — there is in practice not much more freedom. The government allows a small measure of criticism of bureaucracy or government actions but reporters have not fully tried to push barriers until they push back. Self censorship is endemic and might be one reason why reporters do not languish in prison as they do in Vietnam or China. Stories on culture and social ills are permitted to a degree, but rigorous investigation of, for example, detainment in rehabilitation centres for all drug users might be going too far.

There is also the tricky situation that government bodies rarely respond to media requests and little information is provided to reporters, though a couple of departments do apparently have a communications department. The information that is provided is expected to be used to further the government’s message and aims.

“There is an endemic culture within our society where people are wary of the news media, and adequate protection is not granted to those willing to speak out on sensitive topics. As such, accessing information is not easy, which makes presenting it even harder”, said a Vientiane Times report quoted by a Southeast Asia Press Association report from 2012.

News on HMong returning refugees, hydro plants, land clearance and illegal logging — some of the most contentious issues in the country — do not make it into the news often. Many of the issues of concern to Lao people can thus remain localised either with those directly affected or educated urban dwellers able to afford access to foreign news sources. It does not appear activist groups have mass organised online yet. Those with access to Thai media may be able to learn more — the government does not block the Thai channels whose broadcasts make it into border areas.

There have been some moves towards private media ownership, although some sources have remarked the industry is too small and rewards too low at this point for anything but a nascent media industry. “There have been a few attempts to launch more trendy, lifestyle magazines, but most have been short lived, I suspect because the relatively small market size for this does not make it economically viable,” said one anonymous source.

There are really no permanent foreign news bureaus in Laos. Though Voice of Vietnam opened a bureau in 2010 and both Radio France International and China Radio International have broadcast from Laos. It should be noted that the 2008 media law does allow foreign news but Stuart-Fox argues that the hoops foreign papers must jump through are too difficult for it to be worth their while.

Problems of censorship go beyond no free press: even if a savvy reporter could persuade an editor to run stories on corruption finding any hard data would be difficult. Party members do not have to disclose their holdings or assets meaning their ownership of firms in Laos is hard to track down. A lack of data cannot be blamed simply on wilful or mendacious opacity; there is not always the capacity for nation-wide gathering and management of statistics.

It is also worth noting, as Stuart-Fox has, that Laos historically has a lower level of literacy and literary traditions than Vietnam. Policy documents often remain unread (many laws have been drafted with foreign help but few ranking civil servants remain au fait with them) and the fierce, bookish debate of intellectuals can be less prevalent in Laos than its Confucian neighbours. On the upside, Lao officials are sometimes, he says, more amenable to friendly informal chats over a Beer Lao or two.

Laos has some two dozen newspapers and almost twice as many radio stations–useful when one considers how remote some communities are. There has been investment into telecommunications infrastructure which better connects Laos to the ASEAN region.

The Southeast Asia Press Alliance wrote in 2012: “The launching of the country’s stock market towards the end of 2010 should be seen as a welcome step towards greater access to information inside this secluded communist regime as foreign investors need a more transparent government and greater access to its policies on social and economic development.” The World Bank ranked Laos at 159 out of 189 nations for ease of doing business, up from 163 the previous year.

Not all censorship is political. Authorities and the older generation worry about the cultural shifts brought about by rapid modernisation and integration with the wider world. A decade ago young people believed Western influences were “bad” according to a survey published in a 2000 book — Laos at the Crossroads — by authors Vatthana Pholsena and Ruth Banomyong. Today, there are still moves by the government toward modesty and a “Lao” way of being that encompasses tradition and religion. Women still largely wear sins — an embroidered sarong, more or less — and until not so long ago long hair on young men was frowned upon or outright illegal — along with earrings or “eccentric clothes”. The same Vientiane Post article quoted also noted that while Western music was technically illegal in nightclubs it could be permissible provided it made up no more than 20 per cent of the music content of the venue, which had to be well-lit to prevent “indecent acts”. However Vientiane’s nightclubs seem to play largely western music or at least the bland, synth-heavy electronica found across the world.

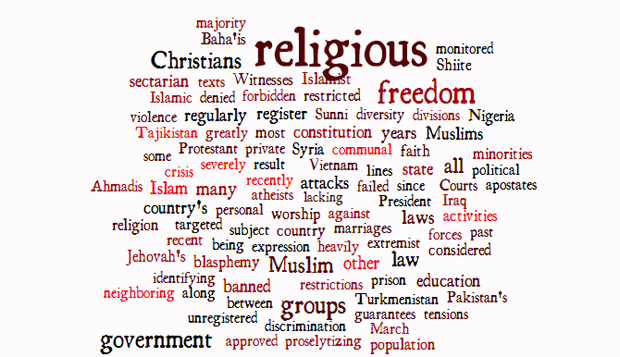

Religious freedom

Laos is Buddhist, which the government recognises and publicly embraces. In fact, it even went so far as to argue, on more than one occasion, that Marxism and Buddhism are not so much mutually exclusive as eminently compatible. The Sangha, the Buddhist clergy, was asked as early as 1975 to study Marxism and be a kind of emissary or teacher of the doctrine especially to those in the countryside. Regimes in Southeast Asia reasserting legitimacy by linking themselves with the nation’s dominant religion is not new and serves a useful dual purpose: They are linked to something deeply esteemed by the people but also more able to control what could otherwise be a powerful dissenting force.

Christians face more persecution on the whole. Hmong Protestant Christians — as opposed to Catholic groups — possibly the more so. The Hmong were co-opted by US forces during the Secret War when the United States undertook a covert bombing of the nation to disrupt the supply chains operating through the Ho Chi Minh Trail that assisted Vietnamese forces.

It is important also to understand that though many Hmong face difficulties in the nation and are discriminated against, it is largely the Christian Hmong who face the worst persecution, similar to Central Highlands Protestants in Vietnam, who are loosely grouped under the umbrella term Degar. Both of these cases stem from involvement with and support of US forces during wartime. Lao Hmong in the United States make up a reasonable sized diaspora and the older generation not only rails against the communist government but enjoys support from US veteran’s advocate group the CPPP — which erroneously reported the murder of 72 Hmong by Vietnamese-trained Lao forces in 2011. Former leader, the late Vang Pao, went so far to plan a coup from his home in California. Many Hmong who fled to Thailand during the war years and remained in limbo were forcibly repatriated a few years ago.

According to Stuart-Fox, Hmong who have maintained their traditional animist beliefs or became party-friendly communists do not suffer the same discrimination or persecution. One woman even made it into the Politburo.

Laos’ multitudinous ethnic minorities also follow many religions and the government officially allows this and officially advocates religious freedom. However this only goes so far as preserving or allowing “good” practices. Religious ceremonies considered backward have been suppressed where possible — like slaughter of animals in rituals. “Superstition” is not kindly looked upon.

Digital freedom

Internet access is far lower than any of Laos’ neighbours with only 9 percent using it in 2011. More recent data suggests an expansion: In 2012 there were 400,000 Facebook users in Laos; up from 60,000 in 2011 in a population of over 6.5 million.

Internet use is growing in Laos but still remains confined to larger cities and towns. A report from academic Warren Mayes guesstimated there were some 50-60 internet cafes in Vientiane in 2006. He noted then online life was growing fast for young people and their interactions with the wider Lao diaspora.

Laos may yet crackdown on Facebook. Last year the communications ministry was to introduce internet regulations to allow official monitoring of the internet — though sources suggest it is already very much unofficially monitored. The director general mentioned to the Vientiane Times information on Facebook circulating regarding a crashed Lao Airlines plane was not “helpful”.

The state controls all internet service providers, and there are some reports that the government sporadically blocks web activity. “The government’s technical ability to monitor the internet is limited, though concerns remain that Laos is looking to adopt the censorship policies and technologies of its neighbors, Vietnam and China,” says Freedom House.

Much of Vietnam’s surveillance ability is already sourced from western companies such as Finn Fisher, Verint and Silver Bullet, rather than homegrown. Sources have previously told Index that Chinese private companies are more likely to assist in surveillance than the government proper; however many including the CPJ strongly suspect Chinese government involvement.

One problem for Laos is that Lao language and alphabet programs have been slow to catch up, though young people do use a phonetic, romanised script known as pasa karaoke.

Deputy Minister of Post and Telecommunications, Thansamay Kommasith, told the Vientiane Times that an “official” Lao script program was being developed, saying: “This is for unity and prosperity, using the official Lao language in those technologies for the future development of IT in Laos as well as to develop the country through them.” There are already unofficial ones being used. Vietnamese military-owned telco Viettel is to assist in the development, according to local news stories. The telco was previously linked to malware attacks within Vietnam.

Laos has plans to launch its own communications satellite. Minister of Post and Telecommunication, Hiem Phommachanh, said at a “groundbreaking ceremony” the satellite would contribute to the nation’s socio-economic development. The $250 million (£147 million) satellite will be funded by China, though Laos will hold a 30 per cent share.

Formerly message boards like Laoupdate and Laosmiles have been popular with both the younger diaspora and native Lao. The former site shut down, some suggest thanks to government pressure. The latter censored posts, explaining earnestly to the outraged users that it was to avoid trouble.

The Electronic Freedom Frontier has reported that Laos is on the Global Online Freedom Act’s blacklist, which was passed by a US House sub-committee, meaning US companies are prohibited from selling surveillance gear to repressive regimes. The EFF called it “an important step toward protecting human rights and free expression online”. US companies have sold such technology in the past to Vietnam.

Just as Laos has laws which can govern the press or activists, it has also specified similar acts in its internet laws. Article 15 (points 6 and 7) states people must “Not to use communication to defeat national stability, peace, socio-economic or cultural development of the country”; “7. Not to use the telecommunication system to defame persons or organisations.”

Staying friendly with the neighbours

Laos, neighbour to Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, China and Burma, has long been called land-locked for its lack of access to any sea. With so many roads being built, Chinese railway funding and Laos’ own ambition to turn itself into a goods transport corridor it’s now more often called “land-linked”. But Laos has been balancing its neighbours and acting as either a buffer or corridor for a long time.

Historically beset from three sides by China, Vietnam and Thailand the nation has learned how to balance its neighbours’ needs and demands while paying expected tribute and playing them off against one another. Laos shares religion, a measure of culture and language with Thailand, as well as strong cross-border trade and cultural products like television shows and popular music. China and Vietnam have more invested both politically and economically. China’s projects and influence are seen more in the north of the nation; Vietnam in the south.

While China cooperates with the party and offers no criticism, Vietnam has more invested in the party. Both Professor Carl Thayer of the Australian Defence Force Academy and Stuart-Fox say that Vietnam has a greater interest in the political status quo in Laos being maintained. A change in regime could have repercussions for Hanoi. Vietnam has traditionally offered more political guidance and military assistance. The two nations also have a shared wartime history. But it has been Chinese involvement in Laos that has prompted some of the few public demonstrations, though protests over land reclamation often related to dams are also growing.

For example, the New City Development would have involved 50,000 Chinese workers to build the stadium for the 2009 SEA Games. It was met with public opposition and even members of the largely party-member legislative National Assembly disapproved. There are also many towns, especially in the north, with large Chinese populations, Chinese markets and even signage in Chinese. Some in Laos have publicly wondered why, for example, Chinese workers must be imported for Chinese building projects when Laos has its own workers available.

China exerts political influence by virtue of not trying to. Unlike western aid, packages from China are not conditional upon human rights. China has a policy of non-intervention, though this is true for all nations it aids and invests in; there has been criticism of its similar policies in Africa. The two nations raised their bilateral relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2009. Chinese development aid from 1997 to 2007 was estimated at $280 million and the nation provided another $330 million from 1998 – 2001, according to Thayer.

The problems already present in Laos such as lack of transparency, corruption and environmental degradation have been raised as issues in regard to Chinese investment also by western aid agencies and NGOs and concerned Lao. At the same time there are worries about Chinese goods pushing out locally-made goods.

The ongoing non-investigation

Writing in the Asia Times in February, more than a year after Somphone went missing, his wife Shui Meng Ng pointed out that his disappearance has barely been mentioned in the local press and certainly no words of distemper from the foreign press have made it into local news. Questions on his whereabouts have been met with official blandness: “We have found nothing yet, but the relevant authorities are still doing their best to investigate the case.”

The European Parliament expressed grave concern, and many foreign aid groups and private NGOs have also tried to put pressure to bear on the government to explain or transparently investigate the man’s disappearance. The government, it seems, does not care. “Tough words,” from these groups she writes “have not been followed by equally tough actions.” She described questions by resident or visiting dignitaries as an “irritation” to local officials but nothing more.“Within Lao officialdom, no one wants to hear his name, no one wants to be reminded of his disappearance, and no one dares to talk openly about him.”

Given few in Laos read much aside from the official papers it is easy enough to whitewash his disappearance. Another source speaking to Index suggested a certain laissez-faire attitude even among some local, educated aid workers, characterised with: “Well, he should have known what might happen to him for speaking up so much.”

Ng makes a useful point: The nation’s steadfast drive to greater international and regional roles is, seemingly, belied by its refusal to even acknowledge what has gone wrong, or why.

Human rights and freedom of speech are not, despite what we would often like to believe, essential for a well respected global role. But for small, hitherto forgotten and least developed nations, a respect for international norms helps ease notions of “backwardness”.

This article was published on May 12, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org